Charles Walter Turner

Family

Charles Walter Turner was born in 1897 in Dartmouth. He was the youngest surviving son of William Henry Stephens Turner and his wife, Rosa Ann Kelland, both born in Dartmouth.

William Turner was baptised at St Saviour's, Dartmouth on 29th June 1860. His father, Thomas Turner, was a shipwright. He died in 1862 when William was only two years old, leaving William's mother Elizabeth Harriet (nee Stephens) with two very young children - William's sister, Blanche Louisa, was born only a couple of months before Thomas died. Elizabeth Turner remarried in 1864. Her second husband, John Carley, was a seaman in the Royal Navy, who then transferred to the Coastguard Service. By the time of the 1871 Census, John was stationed at Eastbourne, living in the Coastguard Cottages with Elizabeth and Blanche. William, in the meantime, was living in Horn Lane, Dartmouth with his grandmother, Harriet Stephens, and her second husband, Henry Veale, a builder and mason. Most probably for this reason, William became a mason too.

Rosa Ann Kelland was baptised at St Petrox, Dartmouth, a few months earlier than her future husband, on 28th September 1859. Her parents, Robert and Susan Elizabeth Kelland, took three of their children to St Petrox to be christened on that day - Mary Moore, born 30th May 1854, Francis Arthur, born 2nd March 1857, and Rosa, born two weeks before the ceremony, on 12th September 1859. Rosa was the seventh child born to Robert and Susan; the baptism register at St Petrox also records two more. In most of those records, Robert Kelland was described as a shoemaker; however, he also seems to have developed a second career, for at the time of the baptism of his son Alfred Edward, on 26th April 1863, he was the "Master of the steamer Dart". In the 1871 Census, Robert and Susan lived in Coles Court. Still living home were Francis, apprenticed to a painter, and the three youngest children, Rosa, Alfred, and Caroline, all "scholars". Robert was a "Master of River Steamboat".

William and Rosa married on 2nd February 1879 at the Baptist Meeting House in Atkins Lane, South Town, Dartmouth. They were both only eighteen years old. Their eldest son was born shortly afterwards, on 12th April 1879, and baptised at St Petrox on 11th May 1879. He was named William John Carley Turner, apparently partly for William himself and partly for his stepfather. John Carley retired from the Coastguard Service later that year, and he and Harriet (with William's sister Blanche) returned to Devon to run the Sportsman's Arms, at Hemborough Post, near Blackawton.

Where William and Rose began married life is not clear. They may have lived with Robert and Susan Kelland in Coles Court - Rosa and William junior were recorded there in the 1881 Census. We have been unable to trace William's whereabouts in that Census, so perhaps he was working away from home. Rosa and William's eldest daughter, Harriet Blanche, was born in Dartmouth just after the Census, on 28th April 1881, but baptised on 10th July 1881 at St John's, Paignton, suggesting that, after the second baby was born, the family may have moved away from Dartmouth for a brief period.

By the time of the birth of their third child, Francis Arthur Kelland, named for Rosa's brother, William and Rosa had moved back to Dartmouth. Francis was born on 16th May 1883 and baptised at St Saviours on 14th June of that year. He was followed swiftly by Robert Henry, born 26th August 1884, baptised at St Saviours on 19th October; by Rosa Ann, born 16th February 1887 and baptised at St Saviours on 17th April; and Harry, born 8th October 1889, and baptised at St Saviours on 29th January 1890. The 1891 Census recorded William, Rosa, and their six children living in Crowthers Hill. William continued to work in the building trade as a mason.

Over the next ten years, the baptism registers of St Saviours continued to record William and Rosa's growing family: George Demarche (Demarche was Rosa's mother's maiden name), on 18th August 1892; Freda Louise, on 27th September 1894; Alfred Edward and Charles Walter, baptised together on 15th July 1897 (Alfred Edward was eighteen months old, and Charles Walter a newborn); and Margaret Stanning, on 3rd March 1899. Sadly Margaret died later that year - she was buried at Longcross Cemetery on 4th October 1899, aged seven months. She had been named for Rosa's father's second wife; Rosa's mother, Susan, had died in 1886, and her father Robert had married Margaret Stanning Coaker in 1888. Robert himself died soon after little Margaret, on 18th December 1899. William had also lost his mother, Harriet Carley, at the beginning of 1899 (she had been widowed for a second time in 1890).

Meanwhile, the older members of the family were beginning their working lives. All the boys who survived to adulthood, except for Charles Walter, joined the Royal Navy sooner or later. William (junior) was the first - he joined HMS Britannia (still at that stage in the old training ships in the Dart) on 26th June 1896 as a Domestic 3rd Class, becoming a Sick Bay Attendant in 1899. During the early part of his career, he mostly alternated between HMS Britannia and Plymouth Hospital, so he probably returned home frequently. Francis followed his elder brother into the Navy three years later, joining HMS Impregnable on 24th July 1899 as a Boy 2nd Class; and Robert Henry joined only a few months later, joining HMS Impregnable as a Boy 2nd Class on 2nd January 1900.

At the 1901 Census, William and Rosa were still living in Crowthers Hill, and William continued to work as a mason. The three eldest boys were all away in the Navy, and Harriet Blanche was also not at home (we have not been able to trace her whereabouts in the Census). So there were still six children at home: Rosa (junior), Harry, George, Freda, Alfred, and Charles. Charles' position as the baby of the family was about to change, however - William and Rosa's last child, Albert Edward, was born only a few weeks after the Census was taken, on 20th May 1901.

Over the next few years, as Charles grew up, his family continued to change gradually. Harriet Blanche married George Heard, a sailor, at St Petrox in 1902, and moved to Tollesbury, Essex. Harry was the next to join his brothers in the Navy, joining HMS Impregnable on 10th September 1905 as a Boy 2nd Class. Baby Albert, who was perhaps always frail, was privately baptised on 16th July 1906, and buried four days later at Longcross, aged five. By this time, William and Rosa had moved to 2, South Ford Road.

The death of William and Rosa's youngest son was followed only six months later by the death of their eldest, William John. He had been promoted 2nd Class Sick Bay Steward on 19th January 1904, but he himself fell sick during his service in HMS Cornwallis in 1906. He was invalided out of the Navy on 25th January 1907 and died on 11th February at South Ford Road, aged 27. He too was buried at Longcross. William and Rosa felt this loss deeply, marking the anniversary of his death in the Dartmouth Chronicle for several years.

More happily, Rosa Ann married Henry John Hibbs in St Saviours on 23rd June 1907. Her brothers Francis and Robert were the two witnesses. Henry Hibbs was a drayman at Warfleet Brewery, and he and Rosa remained in Warfleet after their marriage. By 1911, they had two boys, named after four of her brothers (as well as her husband) - Henry William Robert, and George Francis. Rosa and Henry remained in Dartmouth until after the war.

Robert's time in the Navy came to a premature end on 3rd November 1909, when he was invalided out with tuberculosis. He was able to obtain work, however - when he married Maria Wallace in Strete in 1913, he was working as a Chauffeur in Haslemere, Surrey. Meantime, following the now-established path for the boys of the family, George had joined the Royal Naval College as an Officer's Clerk 3rd Class in 1908, rejoining on a new continuous service engagement as a Stoker II on 29th March 1910.

The 1911 Census recorded William, Rosa, and three of their children at 2, South Ford Road, Dartmouth. William now described himself as "bricklayer [working in] building industry". George was (apparently) home on leave from the Naval Base at Devonport (in which he was serving at the time); Alfred had not yet joined the Navy, but, aged 15, was working at the Royal Naval College as a "page boy"; and Charles had also begun his working life, as a Printer's errand boy. Freda Louise (recorded as Louise) was in domestic service not far away - she was a housemaid in the household of Brantford Hartland, the Headmaster of Paignton College, and his wife and family.

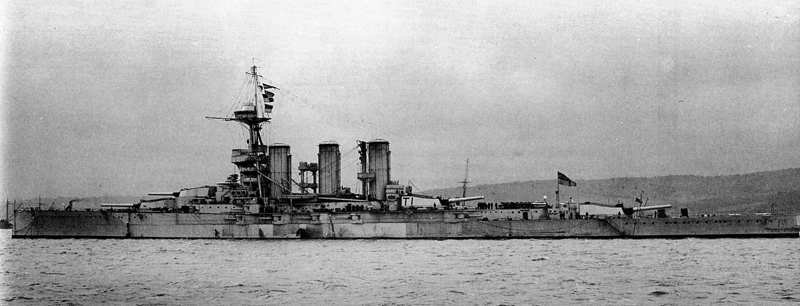

A few months later, Alfred took the same route into the service as his brother George, joining the Navy as an Officer's Clerk 3rd Class on 23rd September 1911. However, he did not serve for long, being discharged sick on 2nd April 1913. He died two months later, and was buried at Longcross on 19th July 1913. By this time, Harry had also left the Navy, being invalided out with kidney disease in 1912. By the time the war began, William and Rosa had two sons in the Navy: Francis was serving in the battleship HMS Collingwood, and George was appointed to the battlecruiser HMS Tiger as she was commissioned, on 3rd October 1914. Both served in these ships throughout the war.

Service

Whether Charles tried to join the Navy after the war began is not known, but he must have been keen to "do his bit", because his name appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle's weekly "Roll of Honour" of those serving in HM Forces on 18th and 25th December 1914. By that date, he had joined the Devonshire Regiment and had been posted to the 10th (Service) Battalion. Exactly when he joined up is not known, because his papers have not survived - at the time of his death it was said that he "enlisted immediately after the outbreak of war". However, some indication may be obtained by looking at the surviving papers of those men joining the Devonshire Regiment with service numbers very close to his (14509). These suggest that he may have joined around the middle of November 1914.

At this stage, the minimum age for enlistment into the Regular army was eighteen, whilst overseas service was not permitted until the age of nineteen (subject to certain dispensations for those in Boy Service or with specific technical abilities in the Royal Engineers). Charles was a few months over seventeen, so it is highly likely he overstated his age by a few more months, or that the recruiting sergeant turned a blind eye.

The 10th (Service) Battalion was formed as part of "K3", the "Third New Army" formed by Lord Kitchener, authorised in September 1914. The battalion was allocated to the 26th Division, which began to form at Stockton Camp, west of Salisbury. According to C T Atkinson:

Equipment and facilities for training were rather deficient in the early days; recruits had been served out with a knife and fork apiece, but had no spoons, and the tent orderlies found it extraordinarily difficult to serve the dinners from the dixies until a consignment of ladles was acquired from Salisbury ... The 10th spent about two months on the Plain, at first enjoying excellent weather, but in November rain began, and before long mud compelled a retirement into billets for the winter, at Bath. Shortly after reaching Bath the first issue of khaki was made ... At Bath the 10th were extremely comfortable, though they were kept busy ... musketry was a difficulty; it was a long time before Service rifles could be provided ... In April came a 21 mile march to a standing camp at Sutton Veney, three miles from Warminster, where the Division was concentrating. Here the battalion ... was promoted from battalion training to brigade and divisional exercises.

The 10th Battalion was ordered overseas to France in September 1915, the main body of the battalion crossing from Folkestone to Boulogne on 23rd September, and arriving with the rest of the brigade near Amiens on 25th September, as the 8th and 9th Battalions (which included many men from Dartmouth) attacked at the Battle of Loos. The 10th spent most of October in training, but just as they had reached Sailly-Laurette, to be attached to the 1st Devons for instruction in trench warfare, they received orders to "about turn", and prepare for embarkation at Marseilles. They had been ordered to go to Salonika.

When they arrived in Marseilles on 13th November, they:

... marched down to the quay to find confusion reigning; no-one seemed to have definite orders, and the place was congested with troops and transport. In the end Battalion HQ with A and B Companies embarked on the transport "Ivernia" along with another battalion and a half and a brigade staff. C and D shipped on the battleship "Hannibal" ... but ... the transport and the Lewis guns got left behind and did not rejoin until the 10th had already had three weeks experience of ... Macedonia.

Salonika

The background to the 10th Battalion's sudden redeployment was the developing threat that Bulgaria would ally with Germany and Austria to attack Serbia. To prevent this, the Allies formed the Salonika Expeditionary Force. Notwithstanding official Greek neutrality (and profiting from divisions between King Constantine, who favoured the Central Powers, and his Prime Minister Eleutherios Venizelos, who favoured the Allies), the Greek port of Salonika was used as the base for the launch of the campaign. One French and one British division were sent to begin with, but, according to Peter Hart, by the time they arrived:

... whatever the SEF had been meant to achieve had been rendered redundant ... The most [the French General Serail, in overall command] could hope to achieve was to hold open a line of retreat for the Serbs. When the British finally moved forward in early November, it was all far too little too late ... as the British and French fell back, they formed a line just inside the Greek border to try to hold back the Bulgarians. The British wanted to evacuate, but the French would not consider it ... The Salonika Front became a permanent fixture for the rest of the war: fighting the Bulgarians for reasons that seem opaque to this day.

The 26th Division was one of five British divisions sent to the area, while the French eventually had nine serving there; other countries also contributed forces, but:

Despite all their efforts, the Allies still only had enough forces to defend themselves, and not enough to attack with much hope of success. As the Bulgarians were forbidden to press into Greece by the Germans, fearful of triggering direct Greek involvement in the war, there they [stayed] in static oblivion".

For the 10th Battalion, the first part of 1916 was a period of very little action. They were put first to making roads, to enable proper supply lines to be established to the front line, and then to trench construction. In June, according to Atkinson, they:

moved into Salonika to take over garrison duties of a multifarious but uninspiring character, in which fire alarms afforded the nearest approach to excitement".

On 30th July, however, they were brought back up to the front line, and on 22nd August, were involved in repelling a Bulgarian attack. They remained in the same area for the next few weeks. However, the principal cause of casualties at this period was not the Bulgarians, but the conditions. In August and September 1916, many men were hospitalised by malaria and dysentery, and numbers fell much below strength. It seems that Charles was one of those badly affected; the short piece published about him in the Dartmouth Chronicle in December 1917 (see below) reported that "he was home on leave last summer after having suffered malaria, dysentery and typhoid in Salonika".

How long Charles was at home is not known, but he did not return to Salonika, instead being sent to France to join the 9th Devons. He may well have been delighted to leave Macedonia, but what he faced in Flanders was far worse.

France and Flanders

The 8th and 9th Devons were both part of the Seventh Division, having arrived in France in 1915. For the 9th Devons experiences to April 1917, see the stories of Robert Phillips Willing, Ernest Leonard Memory, Thomas Alfred Smith and Samuel Courtman. After the attack on Ecoust, they had been involved in an attack on Bullecourt on 7th/8th May, followed by a period of comparative quiet in the front line, and an extended period of training in August.

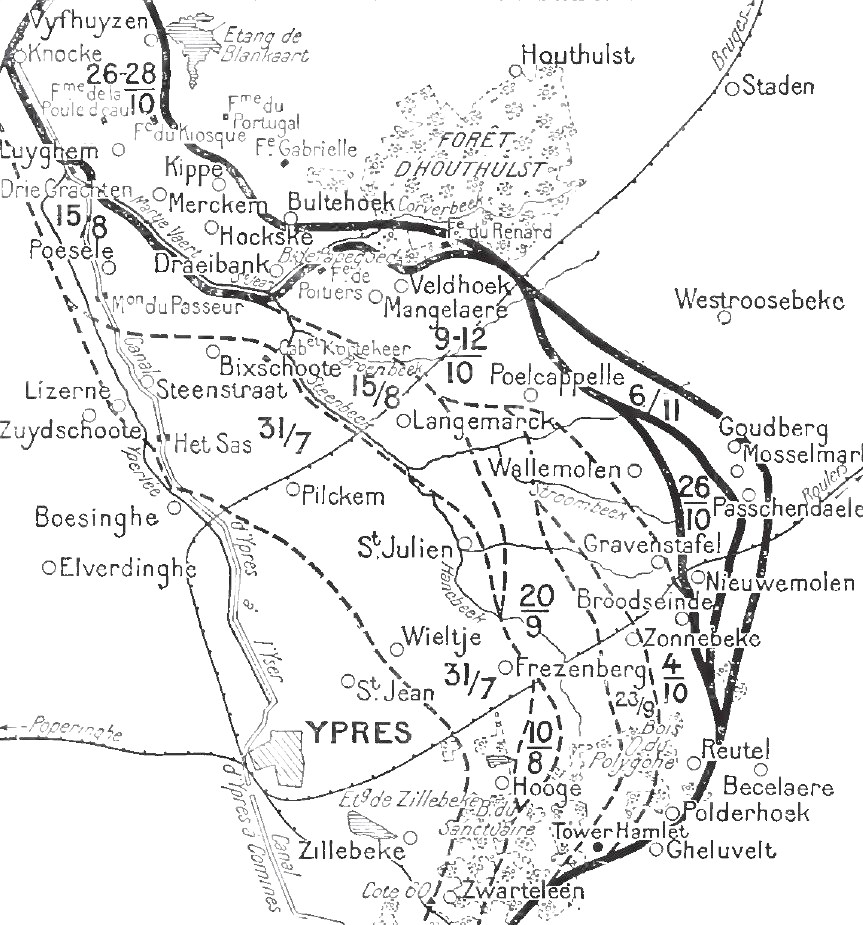

The 8th and 9th Devons were moved up to Flanders on 29th August 1917, where the Third Battle of Ypres had started nearly a month earlier. (For the background to this offensive, see the story of William John Farrow Bates, killed on the first day of the battle on 31st July 1917). Throughout September, however, they remained well to the rear, continuing to train and absorb drafts of reinforcements. They were brought forward on 29th September to take part in the renewed offensive. On 4th October, the Seventh Division took part in the Battle of Broodseinde - see the story of John Samuel Webber, killed on 7th October while the 8th Devons held the position they had gained in the attack.

On the day of that attack, the 9th Devons were in reserve, and spent most of 4th and 5th October finding carrying parties and bringing down wounded. They were brought into the line on 6th October and remained there for four days. The positions they held were heavily shelled on 10th October, and by the time they were relieved that evening they had lost nearly as heavily as the 8th Devons, who had led the attack.

The Devons were next brought into the continuing battle on 26th October, the start of what is now called the Second Battle of Passchendaele, the final phase of the Third Battle of Ypres. The attack on the Passchendaele Ridge itself was the responsibility of the Canadian Corps; it fell to the British Fifth and Seventh Divisions to mount a "diversionary" attack to the south, intended to pin down German reserves and prevent them being redeployed against the main offensive. The Seventh Division's objective was the village of Gheluvelt, on the Menin Road.

The conditions were appalling, for it had rained heavily during most of October, once again turning the battlefield into a morass, and both the 8th and 9th Devons were well below strength because of the casualties earlier in the month. The fortnight's "rest" had offered little real respite - due to the conditions, "training was difficult, recreation barely possible, real rest unattainable, as the camps were within reach of the German long-range guns, and their aeroplanes had now developed night bombing of British camps into a regular system".

Across the Seventh Division's front, the 91st Brigade was on the right, south of the Menin Road, and the 20th Brigade was positioned either side of the road. Within the Brigade front, the Borders were on the right (with the Gordons in support) and the Devons were on the left, immediately to the north of the road. This time, the 9th Devons led the attack, with the 8th Devons in support. The 9th Devons objective was the "Red Line", which ran through the middle of the village approximately south-west to north-east, just east of Gheluvelt church. If they achieved this, the 8th Devons were to "leap-frog" over them to a "Blue Line", in effect taking the whole of the rest of the village. They faced, as elsewhere, a series of strongly fortified and held pillboxes and consolidated shell-holes.

Zero-hour was 5.40am, and despite enemy shelling of the support areas, the attack went in on time. However, the Borders on the right immediately met stiff resistance, and were unable to keep up with the Devons. A pillbox known as "Lewis House", south of the road, caused many casualties to the right-hand company of the 9th Devons through enfilade fire, so that the right of the attack fell behind the left. But some, under Captain Pridham of the 9th Devons, were able to consolidate a position just short of the light railway west of the village, though this was not far beyond their starting point. The left-hand company was able to get further, and some men even reached the village, taking a few prisoners.

By this time, the 8th Devons, "leap-frogging" through, had overtaken the 9th, though sustaining many casualties from the enfilade fire. Men from both battalions were "inextricably mixed up" as the attack went further forward and casualties mounted. Some reached a position a little north of Gheluvelt Church, but this proved untenable when an enemy counter-attack was mounted down the light railway line, which ran behind them, and risked cutting them off. The survivors, under Captain Marshall of the 8th Devons, therefore fell back to a "huge shell-crater" outside the village, near, or on, the Menin Road.

Meanwhile, platoons attacking further to the left lost their direction, swinging into the neighbouring Fifth Division's area; one party attempted to attack Gheluvelt Chateau, to the north-east of the village, but was then isolated and came under heavy fire, sustaining many casualties as they withdrew. Others attacking on the right swung across the road in an attempt to rush the enfilading pillboxes, but all were hit. One platoon on the right was seen to reach Gheuvelt, but no survivors ever came back.

Eventually, only Captain Marshall's and Captain Pridham's parties were left, together with a few isolated groups of men in twos and threes in shell-holes. Very few weapons were not clogged with mud and Lewis and Vickers machine guns were out of action. It began to look as if both battalions might be entirely lost.

However, two companies of reinforcements from the Royal Welsh Fusiliers were sent up, and got through despite the impossible conditions; and the Gordons were able to take one of the pillboxes on the right of Captain Marshall's crater, which then enabled a defensive flank to be formed south of the road. At 3pm the judgment was made that anyone in front of the line to which the survivors had fallen back was likely to be dead or a prisoner, and a protective barrage was then put down to deter any possible enemy attack aiming to take advantage of the situation. No such attack was forthcoming, and what was left of the 20th Brigade was relieved at 8pm.

Death

In the 9th Devons, Captain Pridham was the only company officer unhit. Six officers were killed or missing. Of the men, 143 were killed or missing, 151 wounded.

In the 8th Devons, fourteen officers were killed, wounded or missing, with 127 men killed or missing (about 40 of whom were subsequently reported prisoners of war) and 131 wounded.

The Regimental History observes:

October 26th 1917 was the worst day in over two years of terrible days. Heavy loss at Loos, Mametz and Ginchy was the portion of these young battalions but, apart from a tiny share in the possible drawing off of enemy resources from the battle front further north, there was nothing to show for 26th October.

C T Atkinson, writing fairly soon after the events he describes, tried with real feeling to find something positive to say:

... the spirit which had led these two battalions to advance so unflinchingly to an attack they could not but realise to be a forlorn hope, represents a triumph of discipline and esprit de corps. The saddest day in their history, it was, nevertheless, the high water mark of their endeavour.

Charles Turner was one of those whose fate was unknown after the attack. Perhaps because several men had been taken prisoner, his name did not appear in casualty lists for some time. He was eventually declared "missing" in the casualty list of 10th December 1917. The Dartmouth Chronicle duly reported on 14th December 1917:

Missing - Mr and Mrs Turner, of 2 South Ford Road, have, we regret to hear, received an official intimation to the effect that their youngest son, Private Charles Turner, has been missing since October 26th. He was 20 years of age, and enlisted immediately after the outbreak of war. He was home on leave last summer after having suffered from malaria, dysentery and typhoid in Salonika. He was then sent to France, and has since been fighting on the Western Front.

Charles' body was never found (or if found, was not identified), and he was later presumed to have died on or since 26th October 1917. Charles' father William died six months later, on 27th April 1918, aged 57, with his youngest son's fate still unknown.

Commemoration

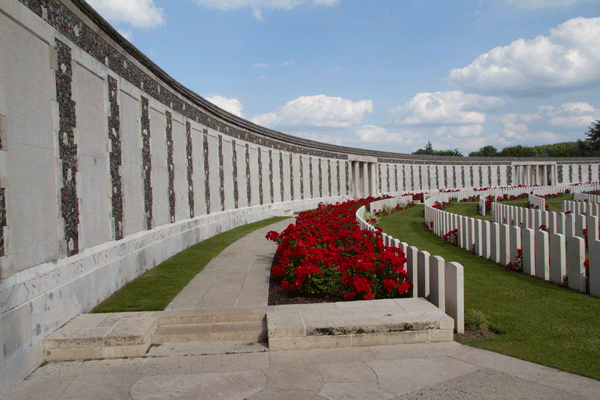

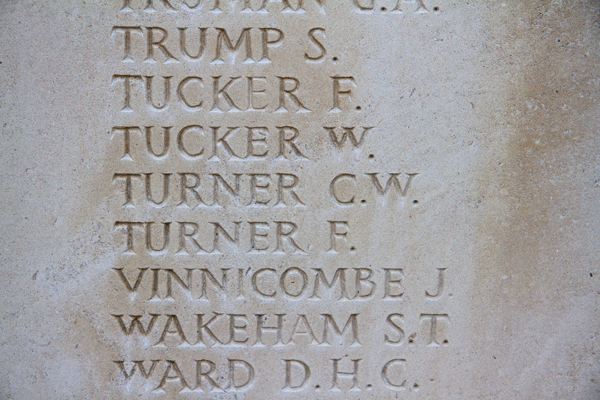

As one of 35,000 men of British and New Zealand forces who died on the Ypres front between August 1917 and November 1918, Charles is commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial Wall to the Missing, which surrounds the Tyne Cot Cemetery.

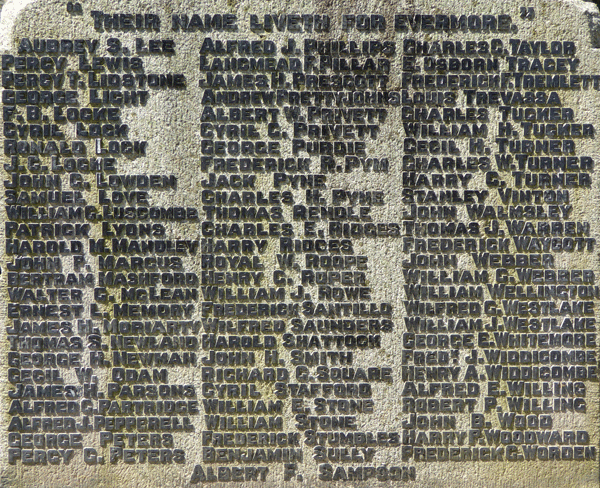

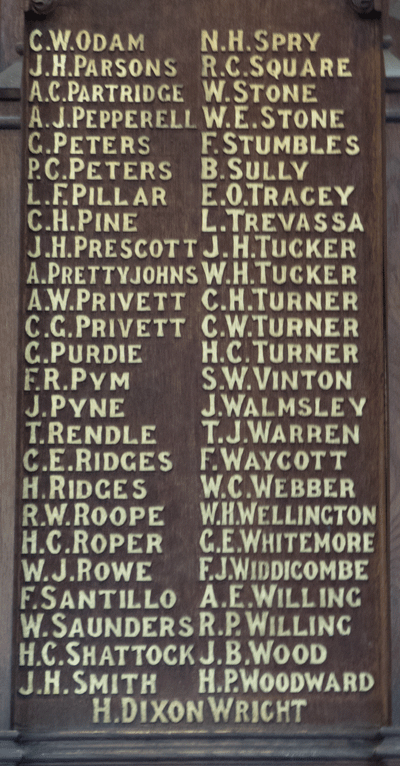

In Dartmouth, Charles is commemorated on the Town War Memorial and on the St Saviours Memorial Board.

Both Charles' brothers still serving in the Royal Navy saw action (including at the Battle of Jutland) and both survived the war.

Sources

The Devonshire Regiment 1914-1918, compiled by C T Atkinson, publ. 1926, London and Exeter

The Bloody Eleventh: History of the Devonshire Regiment, volume III 1914-1969, by W J P Aggett, publ. Devonshire and Dorset Regiment, Exeter, 1995

The Great War 1914-1918, by Peter Hart, publ. 2014, Profile Books

Naval Service Records for Charles' brothers available at the National Archives, fee payable for download, references:

- William Turner: ADM 188/536/354833

- Francis Arthur Kelland Turner: ADM 188/357/205164

- Robert Henry Turner: ADM 188/362/207643

- Harry Turner: ADM 188/416/234698

- George Demarch[e] Turner: ADM 188/988/406 and ADM 188/879/6166

- Alfred Edward Turner: ADM 188/994/3134

Note:

It has been suggested elsewhere that Charles Walter Turner and Harry Cresswell Turner (also on the Dartmouth War Memorial) were brothers. It is clear from our research that this is incorrect. (However, Harry Cresswell Turner and Cecil Hall Turner were brothers - see their stories, already published).

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Turner |

| Forenames: | Charles Walter |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 14509 |

| Military Unit: | 9th Bn Devonshire Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 26 Oct 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 20 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Third Battle of Ypres |

| Place of Death: | Gheluvelt, Belgium |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Tyne Cot Memorial, Belgium |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |