William John Farrow Bates

Family

William John Farrow Bates was born on 19th January 1881 at the family home in Broadstone, Dartmouth, the ninth child of James Holman Bates and his wife Louisa Mitchell. The Bates family was well-known in Dartmouth - William's grandfather, George Bates, was the licensee of the Seven Stars Inn, in Smith Street, for over 45 years. See the story of Lewis George Bates, William's nephew (the son of William's elder brother George).

Some time after 1884, when William was three, his father James became the licensee of another Dartmouth pub, the Steam Packet Inn, in Duke Street. However, James died only two years later, aged only 41. William's mother Louisa took over the license and ran the Inn herself for several years. She remarried in 1888 - her second husband, David, was also named Bates. William thus lived for most of his childhood at the Steam Packet and was recorded there at the time of the 1891 Census.

Service in the Royal Navy

William's first career appears to have been his service in the Royal Navy. On 5th February 1899, William joined HMS Britannia as a Domestic 3rd Class, overstating his age by two years. His naval service record states that he was 5ft 7ins tall, with black hair, brown eyes and a "dark" complexion. Although work on the site of the new college had started the previous year, the Royal Navy's officer training was at that time still accommodated in the ships moored in the River Dart. William was shortly rated Domestic 2nd Class and he remained in Britannia until 12th November 1900, when he was discharged "no longer required".

Service in South Africa

It is possible that his discharge was at his own request, for it seems that William decided to go to South Africa, where the Second Boer War had begun the year before. He joined the Cape Police District 1 Regiment in April 1901. The Cape Police had been established in 1882 and was responsible for law enforcement in the British Cape Colony; over the next ten years, small districts were gradually combined to form larger units, creating District 1 and District 2 in 1892.

On the outbreak of war, the Cape Police were placed under military command. District 1 did not serve as a unit, but in detachments with British and Cape military forces in different parts of the colony and in the neighbouring Boer Republics. According to the South African Medal Roll, William served with the Cape Police in Cape Colony and the Orange Free State.

The Medal Roll states that he was discharged "medically unfit" on 28th February 1902, before the war ended. However, a later report of his experiences in South Africa (see below) suggests that he was still serving in some capacity at the end of the war, when he acted as the guide for a party of officers, including both General Smuts and officers from the British Army, accepting the surrender of a Boer Commando unit.

Further Service in the Royal Navy

.jpg)

Peace was agreed in South Africa on 31st May 1902. William returned to the UK, and rejoined the Royal Navy, on a "non continuous service engagement", as a Domestic 2nd Class, serving in HMS Antelope from 6th July 1903, to 2nd January 1905. Antelope was an Alarm-class torpedo gunboat, about ten years old at the time William joined her.

While serving in HMS Antelope, William married Gertrude Eliza Westcott. Gertrude was the fourth of nine children of Henry Westcott and his second wife, Eliza Jane Hill. Henry was born in Totnes in 1841, but had served in Canada and Ireland, as well as England, after joining the Army in 1859, enlisting for "three pounds and a free Kit". He served with the 17th Foot until 1875, reaching the rank of Colour Sergeant. He married Gertrude's mother, Eliza, in 1874, at the end of a tour of service in Plymouth.

From 1875, he was attached to the 2nd Somerset Light Infantry Militia for five years as a Sergeant, based in Bath. As part of the Childers Reforms of 1881, the 2nd Somerset Light Infantry Militia became the 4th Battalion of the Prince Albert's Light Infantry (Somersetshire Regiment) and Henry Westcott was appointed to the permanent staff in 1880 as a Sergeant, based at the Regiment's Jellallabad Barracks in Taunton. Gertrude was born on 24th July 1882, and baptised on 17th August 1882 at St Mary Magdalene, in Taunton.

Henry Westcott remained on the permanent staff of the 4th Battalion for a little over thirteen years. When he retired finally due to ill health in 1893, he had served in the Army for nearly thirty-five years, and had demonstrated "exemplary" conduct. Gertrude was thus brought up in the Taunton Barracks, moving, when her father retired, to 44 Grays Road, Taunton. She was recorded there with her father and mother, and the rest of her family, in the 1901 Census. Aged 18, she and her elder sister Ethel worked as collar machinists, in one of Taunton's shirt factories. Her younger sisters Helen and Olive worked as "collar creasers".

How, or where, William and Gertrude met is not known - they married in Bristol on 2nd June 1904, and seem to have settled there. Their first son, Horace Mitchell, was born on 28th June 1905, in Portishead, near Bristol.

William served in torpedo gunboats with the Home Fleet until 1908. In January 1905 he was posted to HMS Hussar, a Dryad-class torpedo gunboat built at Devoport Dockyard and commissioned in 1896; and in November 1905, to HMS Speedwell, an older ship, a member of the Sharpshooter class. He served in Speedwell until January 1908, and during his service in Speedwell was rated Officers Steward 2nd Class.

Remaining in the Home Fleet, his next ship was HMS Berwick, a Monmouth-class armoured cruiser, where he served as Officers Steward 1st Class. He was (presumably) on board when the ship was involved in a serious accident, in 1908. She accidentally collided with the destroyer Tiger during an exercise which took place off Portsmouth, designed to test the fleet's defences against a night attack by torpedo boats. Tiger and a second ship, Recruit, were carrying out the night attack - all ships were without lights. Tiger crossed Berwick's bows, was cut in two "as if she was made of paper" (as the newspapers put it) and sank immediately. According to the official statement, reported on 3rd April 1908, 23 survivors were picked up by HMS Berwick and HMS Gladiator, but 35 men were drowned, including HMS Tiger's commanding officer. Another man died after being recovered from the water. By an odd and unhappy coincidence, HMS Gladiator, which had been involved in the rescue, was herself rammed by a merchant ship only a month later, off the Isle of Wight, with 27 further casualties.

William, and no doubt Gertrude, must have been relieved after these incidents to benefit from nearly three months service ashore in Portsmouth, from September 1908. By this time, Gertrude had moved to Portsmouth, where their second child, another boy, Leslie Holman, was born on 30th August 1908, three days before his father left HMS Berwick.

However, from November 1908 until September 1911, William was back at sea, serving as Officers Steward 1st Class in three of the four Warrior-class armoured cruisers - HMS Achilles, HMS Warrior, and very briefly, HMS Cochrane. These were modern ships, having been completed in 1907 (Warrior in December 1906). All were assigned to the Channel and Home Fleets.

In the meantime, Gertrude moved from Portsmouth back to Taunton, close to the rest of her family. Her father Henry had died three years earlier, and her widowed mother, and her youngest sisters Audrey and Grace, were living with Gertrude's elder sister Ethel, who had married. At the time of the 1911 Census, shortly before the end of William's service in Achilles, Gertrude lived at 19 Trinity Street, with her two young sons, aged five and two, and her younger brother Harry, who worked as a "collar cutter".

Notwithstanding his "non-continuous service engagement", William had in fact been in continuous employment with the Navy since rejoining in 1903. However, on 25th September 1911, he was discharged to shore; and a gap followed, until his final period of service in HMS King Alfred, as Officers Chief Steward. King Alfred, an older armoured cruiser, had been the flagship of the China Station until 1910. She then returned to the UK to become the flagship of the Devonport Sub-Division of the Home Fleet. William joined her in Plymouth on 5th January 1912. On 16th September 1912, he was once again discharged "shore -service no longer required", but of "very good character".

Exactly when William and Gertrude brought their family to Dartmouth is not known but it seems that they had returned to the town by 19th January 1915, when their third son, Stanley Douglas, was born. William's mother Louisa had now retired from the Steam Packet Inn, which she had handed over to his sister Blanche and her husband; another brother-in-law, William Sheen, now ran the Seven Stars. William's brother George was still doing well (see the story of Lewis George Bates already referred to).

Army Service

Like so many, William's service papers have not survived. Soldiers Died in the Great War records that he lived in Dartmouth but enlisted in Newton Abbot. A further clue comes from a list appearing in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 24th December 1915 of "Dartmouth men who have joined the Army Reserve" - this includes the name "J F Bates", most probably an error for "W J F Bates". These were men enlisting under the "Derby Scheme", officially known as the "Group Scheme" - the Government's last attempt to raise manpower voluntarily.

Men enlisting under the scheme could choose either to serve immediately, or attest with an obligation to come if called up later on. Attested men were split into two categories, single and married, and each was subdivided into 23 groups according to age. Those choosing to defer their service were transferred into the Army Reserve and sent back home until they were called up - the youngest men were called up first. When William enlisted, he was just short of his 35th birthday, and of course was married. The attraction of the scheme to such men was that, at the time it was introduced, a commitment was made that married men would only be called up after all age groups of single men.

However, fewer single men came forward under the scheme than hoped. Conscription of single men was introduced on 27th January 1916 - from that date, all unmarried or widowed British men, between the ages of 19 and 41, were deemed to have enlisted on 2nd March 1916. During March 1916 also, younger married men were called up under the Derby Scheme. When this led to protests that the Government was failing to honour its previous commitment to married men, the Government's response was to introduce general conscription, by extending the Military Service Act to married men (and lowering the starting age to 18) on 25th May 1916.

William was a member of the 2nd Battalion Devonshire Regiment at the time of his death and the Regiment's Medal Rolls show that he first joined the 8th Battalion. His service number was 26524; some indication of when he may have been mobilised may be derived from looking at men joining the Regiment with similar service numbers, for whom service papers have survived (see, for example, those quoted in the stories of William Elliott Stone and Charles Tucker). William is likely to have been called up around the middle of June 1916, perhaps joining the 8th Battalion towards the end of 1916.

The 8th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment included many Dartmouth men. They had fought at Loos and the Somme, and had suffered many casualties. For their experiences to September 1916, see the story of William Marks Carpenter; for their experiences in late 1916, in 1917 at the Battle of Arras, and shortly thereafter, see the stories of Harry Bowhay and Bertie James Coles.

So far no evidence has come to light enabling us to identify when, or why, William transferred to the 2nd Battalion. The 2nd Battalion's War Diary records several small parties of reinforcements joining during November and December and a large draft of 105 other ranks arriving on 8th January 1917. After this, they received no further drafts until the first half of June 1917, during which a total of 188 other ranks joined. Presumably, therefore, he had joined the Battalion at the latest by 12th June 1917, when the last of these groups arrived.

As one of the Devonshire Regiment's two regular battalions, 2nd Devons had been in Egypt at the outbreak of war, and arrived in France on 6th November 1914. They had fought at Neuve Chapelle and Aubers Ridge in 1915 and at the Somme, transferring to the Cuinchy sector on 14th July 1916, and then to the Loos area. See the story of William Charles Webber, who died of wounds on 18th October 1916. By that time, the 2nd Battalion was back on the Somme.

During March 1917, the 2nd Devons found themselves following up the German planned withdrawal to the newly fortified "Hindenburg Line". As the retreat neared the line, German resistance stiffened - certain villages to the west of the line being designated as places where final rearguard actions would aim to inflict as much damage as possible upon the forces following them. As the Arras Offensive began further north, troops of 8th Division, including the 2nd Devons, attacked the village of Villers-Guislain. Although the 2nd Devons failed to take it, a further assault a few days later was successful, and the neighbouring village of Gonnelieu fell on 21st April. For the next few weeks the Devons were engaged in consolidating the new British line, until they were relieved on 14th May. On 1st June 1917, the Battalion left the area to transfer to Flanders, in preparation for the next stage of the British offensive at what became known as "Third Ypres".

Meanwhile, in March 1917, William had taken the opportunity to revisit his experiences in South Africa. The Dartmouth Chronicle reported on 30th March 1917 with interest that:

General Smuts writes to a Dartmouth soldier

Private W J Bates, a Dartmothian, now in the Signal Section of the Devonshire Regiment, was recently the proud recipient of a letter from the famous South African, General Smuts. During the South African War, Private Bates served in the Cape Mounted Police, and at the conclusion of hostilities he accompanied General Smuts and a party of the imperial Force officers to accept the surrender of a Boer Commando. Private Bates was the conductor of the party. On the arrival of the famous General in England, Private Bates had occasion to communicate with him, and in the course of his reply General Smuts conveys his best wishes for the Dartmothian's future.

Jan Christian Smuts, once the enemy, had now become a much-feted hero due to the perceived success of his campaign to defeat the Germans in East Africa. He had arrived in England on 12th March 1917 to take part in the Imperial War Conference, representing South Africa. He remained in England and subsequently David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister, appointed him a member of the newly formed Cabinet War Policy Committee (see below).

The Third Battle of Ypres: Strategy

On 1st May 1917, General Haig once again stated his view of the situation on the Western Front:

The guiding principles are ... that the first step must always be to wear down the enemy's power of resistance and to continue to do so until he is so weakened that he will be unable to withstand a decisive blow; then with all one's forces to deliver the decisive blow .... the situation is not yet ripe for the decisive blow ... The cause of General Nivelle's comparative failure appears primarily to have been a miscalculation in this respect.

After the failure of the French offensive, and widespread unrest in the French Army, leading in many regiments to mutiny and desertion, General Nivelle was dismissed by the French Government, and Philippe Petain was appointed Commander in Chief of the French Army on 15th May. He began a process of rebuilding morale, and, to that end, ended large-scale attacks in the short term, and introduced regular, longer and more fairly distributed leave. During 1917 France launched no more great offensives, concentrating instead on limited, surprise attacks, in different sectors, after maximum artillery preparation.

Adding to the difficulties of the Allies was the turmoil in Russia, where the Tsar had abdicated in February 1917. The first all-Russia Congress of Workers and Soldiers' Soviets had opened on 3rd June and soon, soldiers were being withdrawn from the eastern front to deal with the domestic unrest. The War Cabinet feared that soon Britain and its dominions might be standing on their own - until the Americans were able to field a substantial army, which was not expected for another two years.

This situation encouraged General Haig to undertake a major offensive in Flanders, which he had wanted to do for a long time. According to David Stevenson:

Respectable strategic considerations favoured Flanders ... The Ypres salient was overlooked by the encircling Messines-Menin-Passchendaele ridges and pounded by German guns concealed on the reverse slopes. British casualties there ran into thousands each month. Five miles east of the ridges lay the junction of Roulers on the key trunk railway runing laterally behind the Germans' front ... Flanders was the basis for the Gotha [bombers] attacking London, and beyond Roulers beckoned the Belgian coast. The light submarines stationed near Bruges and putting to see from Zeebrugge and Ostend formed about a third of the U-boat fleet ... [if the coast could be cleared] he would assist the navy at a critical moment, at long last outflank the Germans, and force them back against the Dutch border or out of the Low Countries altogether.

However, General Haig was also convinced that "Germany was within six months of the total exhaustion of her available manpower if the fighting continues at its present intensity". As his biographer Gary Mead points out, in this he was completely mistaken - but this view of Germany's military situation remained fundamental to his thinking. During several fraught sessions of the War Policy Committee, set up by Lloyd George on 8th June 1917, the pros and cons of the Flanders offensive and other strategic approaches, in particular against Germany's partners, were argued back and forth. In the end, the Flanders offensive was finally approved by the War Cabinet on 20th July, though it was "on no account [to] be allowed to drift into a protracted, costly, and indecisive operation as occurred in the offensive on the Somme".

Tactics

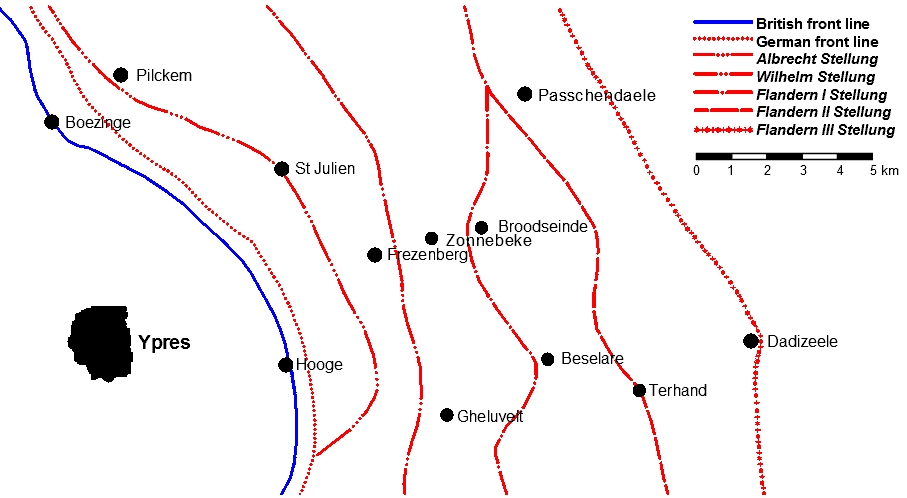

The German defences faced by the British represented "defence in depth". The front line was thinly held, but behind were at least five successive lines - on the Gheluvelt Plateau from Broodseinde to Beselare there were two more - with the rearmost line some seven miles ahead. Across the whole area were concrete pillboxes and fortified farm buildings, sited with interlocking fields of fire. Behind the defensive area, beyond the Gheluvelt Plateau and the Passchendaele Ridge, was the German artillery, hidden from direct British observation.

The original plan, proposed by Generals Plumer and Rawlinson, was cautious, with a first day advance going only as far as the second line of defence. Two days of regroup and recovery would then allow field artillery to be pulled forward to attack the next line - and so on. General Gough, however, proposed a more ambitious plan, involving the capture of three successive lines of defence, all on the first day of the attack; followed by a longer pause before resuming the attack with a further assault aiming at taking the whole Passchendaele ridge. Though this (potentially) would achieve more to begin with, it carried the risk that the attackers would go beyond the range of British artillery protection, with the possibility of major losses and disorganisation. On the other hand, the less ambitious approach ran the risk that opportunities to capitalise on early success would be missed - as, arguably, had been the case after the first day of the Battle of Arras. Haig preferred Gough's approach, though this time there was no talk of "breakthrough", as there had been at the Somme.

The build-up

On 3rd June, the 2nd Devons arrived at Merris, where the 8th Division was coming together to continue training and take in reinforcements. By 12th June, 188 other ranks had joined, though, according to the Regimental History, most had had very little initial training. On 11th June the Division had transferred from the Second Army to General Gough's Fifth Army, which was to lead the attack.

The 2nd Devons moved into the front line on 15th June, where their main task was to dig a new trench "from No 1 Crater to Bellewaerdebeek". In the meantime the CO and Company Commanders attended briefings on "the general outline of operations for the near future". The vulnerability of the British positions around Ypres was clearly illustrated as the Battalion left the line at 11pm. The town was shelled as they marched back to billets - five men were killed, and eleven men and one officer wounded; two of the wounded later died. A second stint in the line, from 25th - 30th June, involved more trench digging, with enemy artillery and aeroplanes "very active".

Most of July, however, was spent training, until 25th July, when they went back into the line, this time in the Railway Wood sector. The following evening a small raid was launched on Identity Trench, the German front line - this was found to be empty, only 18 inches deep and "much knocked about"; however, the second line was held by about 20 men, who opened fire with rifles. The raiding party withdrew, having sustained two casualties.

In the meantime, although the 2nd Devons Battalion War Diary does not refer to it, an immense fifteen day bombardment began on 15th July (five days before the offensive was finally approved), using 3091 guns, from the Fifth and Second Armies, twice as many guns as the Germans had in that sector.

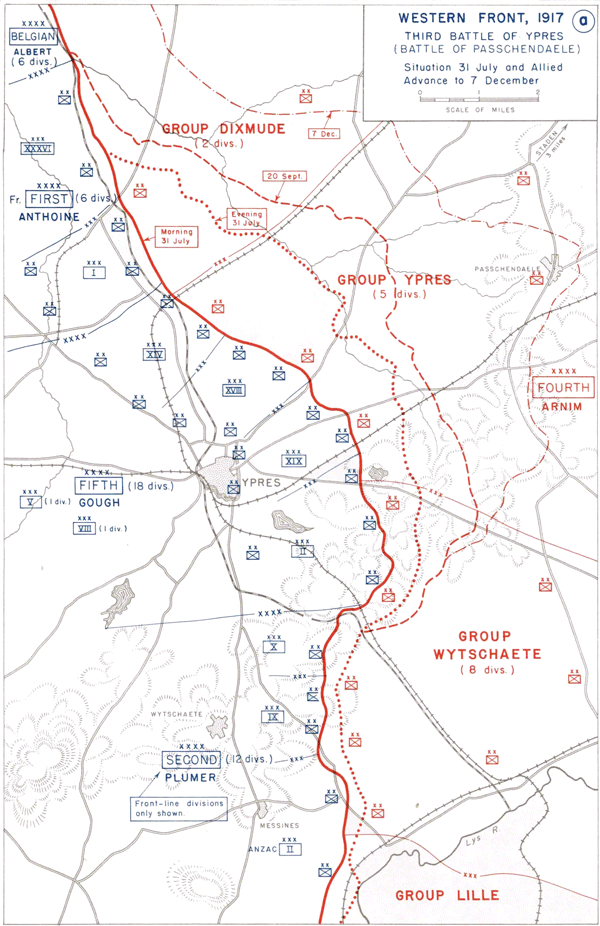

The Fifth Army was to attack on a front of about 7½ miles from south of Zillebeke to Boesinghe. The Second Army, under General Plumer, was to cooperate on the right, extending the area of attack as far south as the Lys River. On the left, the French First Army, under General Anthoine, was to prevent any counter-attack from the north. Fifth Army's front consisted of four Corps, from right to left (south to north): II, XIX, XVIII, XIV.

Eighth Division was on the left of the II Corps front; the 23rd Brigade was on the left of the Divisional front with 24th Brigade on the right and 15th Division on its left, on the other side of the Ypres-Rouler railway. According to the 8th Division's history:

The II Corps front included the difficult area of broken and wooded ground where the Menin Road strikes across the main ridge, and its task took the form of a frontal assault upon a strong and easily defensible position ... Following the general line of the ridge, the depth of our principal objectives increased rapidly from right to left, and ... the 8th Division [had] the widest front of attack of any division in the battle [and] was located at the point where the depth of our objectives was greatest.

The plan involved a series of advances in three stages:

- the 23rd and 24th Brigades were to capture the first two objectives, known as the "Blue" and "Black" lines. The latter corresponded to the ridge just east of the village of Westhoek. Two battalions from each brigade were to capture the Blue line, then the remaining two battalions were to advance to the second objective of the Black line

- the 25th Brigade was then to go through to attack the third objective, the "Green" line, beyond the Hannebeck, assisted by tanks

- the 23rd Brigade was then to follow after the 25th Brigade (having left the 24th Brigade holding the Black Line securely) to assist with taking the attack forward, perhaps to the fourth and final objective, called the "Red" line, at Broodseinde

Zero-hour was 3.50am on 31st July. At the appointed time, the attack was launched. The Regimental History describes the Devons' success in taking the "Blue" line:

The 2nd Devons, on the left of [the 23rd] Brigade, started from the Western portion of Railway Wood ... behind an excellent barrage, the Battalion made splendid progress. It rushed the front line [Identity and Idea Trench] without a check, and swept on over a second and third, both parts of the front system ... [strong points and snipers were overcome] and by 4.50 [am] the Blue line had been taken and news of its capture had reached Brigade HQ.

The Devons and their Brigade companions, the West Yorkshires, began to consolidate their position, while the Middlesex and Scottish Rifles came through as planned to take the Black Line. This was more difficult, because the neighbouring division on the right, 30th Division, had not managed to take the high ground on its section of the Black Line, which overlooked the right sector of the 8th Division; 24th Brigade was thus caught in machine-gun fire from the right. When 25th Brigade attempted to go through to the Green Line, it too was caught in machine-gun fire from the right.

According to the Devons' Regimental History, 23rd Brigade then issued orders to stop the next stage of the advance, but the order never reached the Devons, who, at 10.50am, started forward in support of 25th Brigade, as planned in the third stage of the attack. As they passed through the Black Line they came under machine-gun fire and, according to the Battalion War Diary, "heavy hostile shelling". Several casualties were suffered at this point, including the death of the Battalion's Commanding Officer. Later in the afternoon, 25th Brigade was ordered to retire, and 2nd Devons received orders to withdraw too, to consolidate the position on the Black Line. They remained there overnight, but suffered heavy shelling, causing many casualties. A German counter-attack was launched at about 3pm on 1st August, which the Devons were able to hold off successfully. They were relieved at night, marching back through Ypres in torrential rain to Dominion Camp.

Twenty officers went into the attack; only eight remained unhurt, and two had been killed. Amongst the men, 22 were killed, 170 were wounded, and 37 were missing.

Across the front as a whole, the results of the attack were (according to Peter Hart):

... mixed. On the left the French and their neighbouring divisions had succeeded in over-running two German defensive systems which included both the Pilckem and Bellewaarde Ridges. On the right, on the Gheluvelt Plateau, progress had been far more limited, although even here they had taken the German front line. Together the British and French had suffered losses of about 33,500. German casualties seem to have been around 30,000 ...

(To the north of Ypres, there was more success, the Green line being reached - see the story of Richard Goodman Carder, also killed on the first day of the battle).

Death

It seems that William was one of the 37 men recorded as missing after the attack, and he was duly reported with 21 others from the Regiment as "missing" in a casualty list dated 14th September 1917 (published on 18th September). Either his body was never found, or was not identified - the Devonshire Regiment Medal Roll records him as "death regarded 31st July 1917" and the Soldiers Effects Register as "presumed dead 31st July 1917".

Commemoration

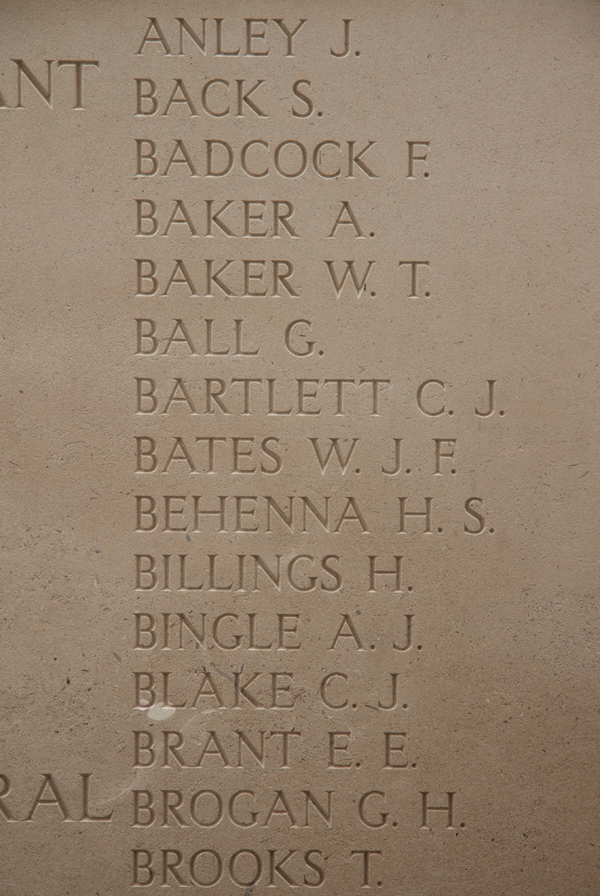

William is thus commemorated on the Menin Gate at Ypres, close to where the 2nd Devons attacked on the day he was presumed to have died.

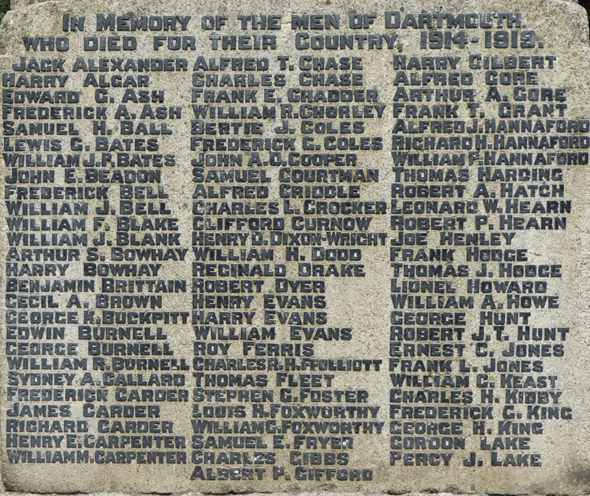

In Dartmouth, he is commemorated on the Town War Memorial. An error appears to have been made when recording his name on the memorial as the initial "P" was used instead of "F".

Sources

The Naval Service Record for William John Farrow Bates is available for download from the National Archives, fee payable, reference ADM 188/541/357185

Army Service record for Henry Westcott from The National Archives, acessed through subscription websites

Attestation Papers for Cape Police indexed on angloboerwar.com

The 2nd Devons War Diary, by Martin Body, 2012, Pollinger in Print

The Devonshire Regiment 1914-1918, compiled by C T Atkinson, 1926, London and Exeter

The Eighth Division 1914-1918, by Lt Col J H Boraston CB, OBE, and Captain Cyril E O Bax, Naval & Military Press

The Great War, by Peter Hart, 2014, Profile Books

The Good Soldier, by Gary Mead, 2014, Atlantic Books

1914-1918, The History of the First World War, by David Stevenson, 2005, 2012, Penguin Books

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Bates |

| Forenames: | William John Farrow |

| Alternative Forenames: | William J F |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 26524 |

| Military Unit: | 2nd Bn Devonshire Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 31 Jul 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 36 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Third Battle of Ypres |

| Place of Death: | Near Ypres |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Menin Gate, Ypres |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |