Lewis George Bates

Family

Lewis George Bates was born on 14th November 1895 in Duke Street, Dartmouth. He was the eldest son of George Edwin Bates and his wife, Annie Emma Howes.

Lewis's great grandfather George Bates was the first of the family to come to Dartmouth. Born in Leicestershire, the son of an earthernware dealer, he was by 1850 the licensee of the Seven Stars Inn, in Smith Street. He ran the inn for over 45 years, and when he and his wife, Mary Ann, celebrated their golden wedding anniversary on 9th March 1892, he was the oldest publican in the town. The Dartmouth Chronicle of 11th March 1892 observed:

During the time he has been occupier of the Inn, he has never had a conviction against him under the licensing laws. His family are well known and deservedly respected.

George Bates' eldest son was James Holman Bates, born in 1844 in South Molton, Devon, before the family's arrival in Dartmouth. He became a carpenter. Some time after 1861, when he was recorded in the Census living with the rest of his family at the Seven Stars, he appears to have moved to London, presumably to work. There in 1866 he married Louisa Mitchell, originally from Exmouth, Devon. They settled in Lambeth, where their eldest son, Warwick Mitchell, was born in 1868. A second child, named George Edwin Bates, was born in Lambeth in 1870, but sadly died when only a few months old.

Perhaps this encouraged the family to come back to the south-west. At the time of the 1871 Census, James Holman Bates had returned to Dartmouth, and was living once again in the family home at the Seven Stars. Louisa was still in London, being recorded (as "Lucy"), with her small son Warwick, in the household of her sister and brother in law, Mary Jane and Ralph Green, who were licensees of the Welsh Harp Inn, in Cornwall Terrace, Battersea. But the family was reunited by the time of the birth of James and Louisa's next child, also named George Edwin Bates, on 28th August 1871 - he was born in the family's new home, in Broadstone, Dartmouth.

It seems that about this time, James decided on a change of career, from now on being variously described as "accountant" or "clerk". The couple's fourth child, Mary Jane, was born in 1873, followed by Louisa Mitchell and Horace Percy in 1875 and 1876 respectively. Sadly, these latter two children both died young - Louisa at only a few months old, and Horace at about eighteen months. Blanche Sommerlad was born in 1877, and survived. Edgar Stockley, born in 1879, died when just over a year old, in 1880.

The couple's ninth child, named William John Farrow Bates, was born in 1881 - he is also on our database. The 1881 Census recorded the family still living in Broadstone, Dartmouth. The surviving children Warwick, George, Mary Jane, and Blanche (though only three) were all at school. The baby, William, was three months old. James worked as a clerk. The couple's tenth and last child, named for his father, James Holman, was born in 1882.

At some time after June 1884, when the previous licensee, Thomas Tucker, had died suddenly, James changed career again, and took over the license of the Steam Packet Inn, in Duke Street. But then James himself died, aged only 41, in 1886. Louisa, left with six children to support, decided to run the Inn herself, and the license was transferred to her. She continued to run it until 1901.

In 1888, Louisa married again, in Exeter. She did not have the inconvenience of changing her name, as her second husband was also named Bates, though there appears to be no prior family connection. David Bates was born in Tilsworth, Bedfordshire. He was also a carpenter by trade, as James had been. By 1888 he was widowed, but without children of his own (so far as we can establish). After his marriage to Louisa, he ran a carpentry and building business in Dartmouth, while Louisa continued to run the Steam Packet Inn. The 1891 Census recorded David and Louisa there, with three of Louisa's children - Mary Jane, Blanche and William.

George Edwin, however, was living with his grandparents, George and Mary Bates, in two rooms at the Seven Stars. He was working as a plumber's apprentice and clearly had ambitions to do well. By 1893, he had set up his own plumbing business, with an associated ironmongery shop, in Duke Street, next door to his mother and stepfather in the Steam Packet Inn. From this time onward, frequent advertisements appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle:

With the business established, George Edwin married Annie Emma Howes, on 3rd December 1894, at St Saviours. Annie was born in Brighton, the only child of a restauranteur, Richard Howes, and his wife Katherine Smith. After the death of her husband, Katherine had returned to live with her father, George Smith, in Beaconsfield, where she and Annie were recorded in the 1881 Census. By the time of the 1891 Census, Annie had moved to Dartmouth, where she lived with her mother's elder sister Jane Smith, and worked in domestic service. George and Annie presumably therefore met in the town.

Lewis was born just under a year later, in November 1895, and a year after that, George Edwin was pleased to announce in the Dartmouth Chronicle that at the technical schools, Plymouth, on 12th December 1896, he had successfully passed the practical examination of the Worshipful Company of Plumbers, London. Six months later, George and Annie's second child, Dorothy Blanche, was born at Duke Street on 30th May 1897, and baptised at St Saviours on 25th June 1897. In the 1901 Census, George, Annie, and the two children were recorded in Duke Street living next door to David and Louisa Bates at the Steam Packet Inn. David Bates had retired, but Louisa still ran the inn. Also living at the Steam Packet was Louisa's eldest son, Warwick, whose occupation was shown as yacht steward, and her youngest son, James, an engine draughtsman.

On 17th January 1902, the Dartmouth Chronicle reported a tragedy in the Bates family. Warwick Bates "had been found dead, hanging by the neck from the bannisters of the stairs at Fern Bank, Victoria Road, under such circumstances as left little room for doubt that he had taken his own life". Both George Edwin Bates, and David Bates, gave evidence to the Coroner's inquest. By then, Louise Bates had handed over the business at the Steam Packet Inn to her daughter Blanche and her husband, William Thomas Dunn; Louise and David had moved to "Fern Bank", but were, apparently, in the habit of frequently staying at the Seven Stars, now run by Louisa's daughter Mary Jane and her husband William J H R Sheen, because Louisa often helped out there.

Warwick had committed suicide whilst he had been left on his own in Fern Bank for a couple of days. George told the inquest that his older brother had not worked for several years, since an injury at Southampton when on board ship. In answer to questions about his brother's health and state of mind, he said that "he had never been properly right since [the injury]" and "was rather eccentric". The jury, given a strong steer by the Coroner, returned a verdict of "Suicide whilst in a state of temporary insanity", and determined the date of death as 14th January 1902. Much sympathy was extended to the Bates family.

Later that year, however, there was happier news, with the birth of Marjory Lauraine, George and Annie's second daughter, on 13th May 1902. Two boys followed - George Tilde, on 6th February 1904, and Arthur James, on 20th March 1905. During this period, George also began to undertake public appointments in Dartmouth, being elected an overseer for Dartmouth (responsible for collecting the poor rate) in March 1902. He was also very active in Dartmouth sports, being a keen member of the swimming club, and representing the town in bowling. (Later, after the war, George was elected to the Town Council, retiring as an alderman).

In 1906, George moved his home and business premises from Duke Street, round the corner to Valentine House, Foss Street. In the advertisements of his change of address, he "thank[ed] his customers for past favours and solicit[ed] a continuance of their custom". He continued to run the plumbing and ironmongery business but Annie, perhaps following her mother in law's example, opened the Valentine Hotel. However, in contrast to the other Bates family establishments in the town, this was a "Temperance" hotel. George, Annie, and their five children were recorded at the Valentine Hotel in Foss Street in the 1911 Census. On Census night, they also had one boarder.

Louisa and David Bates, in the meantime, had moved from Fern Bank, Victoria Road, which no doubt carried very unhappy memories for them, to Port View House, Bayards Cove, where they were recorded in the 1911 Census. (At the same address was Frances Mandley, who had also run one of Dartmouth's pubs - see the story of Harry Mandley).

Lewis, now 15, was recorded in the 1911 Census as a "student". From subsequent records we know that he attended "Torquay Secondary School", as it was then called (it is now the Torquay Boys' Grammar School). The school had been founded in 1904 to train pupil-teachers, becoming a Secondary School by 1912, as the requirements for elementary school teacher training became more rigorous. Already, by this stage, however, by no means all those who attended the school intended to become teachers. In 1910, for example, as Lewis joined, the Western Times reported that there were 38 pupil teachers and 61 scholars, one third of whom came from districts outside Torquay, including Paignton, Brixham, Kingswear and Dartmouth. There was a growing demand for places, particularly from parents who wanted higher education for their children as a general preparation for their future careers, rather than specifically for teaching.

On 19th June 1914, the Western Times reported that:

Ten out of eleven candidates who entered for the preliminary examination for the certificate, 1914, from the Torquay Secondary School, have been successful in passing, and are now eligible for admission to Training Colleges or for recognition as teachers.... successful candidates .... [include] Lewis G Bates (Dartmouth). All these are now completing the last year of a four years' course at the Torquay Secondary School.

But whatever Lewis' intentions about his future career, the war intervened during his summer holidays. He was eighteen years old.

Service

On 25th September 1914, the Dartmouth Chronicle published a list of those serving with "F" Company (Dartmouth) 7th Battalion Devonshire Regiment (Cyclists), including "L Bates". Several men on our database were on the same list - see, for example, Harry Mandley, already referred to; Joe Henley; and Frederick Coles; others joined the Devon Cyclists a little later.

The Devon Cyclists had been created as part of the Territorial Force in 1908. "F" Company was based at Dartmouth and was very much part of the local scene. We don't know whether Lewis joined them before the war, but his appearance on the list in the paper suggests that if he was not already a member, he must have joined very soon after the outbreak of war - his name appears in the list above that of Frederick Coles, who joined on 7th August 1914.

On 29th July 1915, the Western Times reported the unveiling of a "Roll of Honour" at Torquay Secondary School, listing all those from the school who had by then joined the Forces. Lewis' name was included in the list, as a private in the 2nd/7th Battalion Devon Cyclists. As this indicates, the Devon Cyclists had expanded to such an extent after the beginning of the war, that it was possible to form a second Battalion in September 1914. Whereas 1st/7th Battalion, including "F" Company, was sent to the north-east, 2nd/7th Battalion remained in Devon, and sent patrols and coastal reconnaissance parties along the south-west coast from Lyme Regis to Polruan. In November 1915, they moved to Sussex, and in June 1916, to Kent.

During his service with the Devon Cyclists, Lewis evidently demonstrated officer potential, for he was selected as an officer cadet, and was successful. On 7th July 1916, Cadet Lewis George Bates was gazetted a temporary Second Lieutenant, in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. A brief notice of this achievement appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 14th July 1916:

Military promotion

Mr G E Bates, of L'Esperance, Dartmouth, has received information that his son Lewis has been given a commission, and that he has been attached to the 17th Warwicks as second lieutenant.

The 17th (Service) Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment, to which Lewis was attached to begin with, was raised in 1915 for home service. It then became the reserve battalion for the three City of Birmingham infantry battalions - the "Birmingham Pals" - or the 14th, 15th and 16th Warwickshires, as they became. However, Lewis eventually joined none of these. On 20th October 1916, he was posted from the reserve battalion to the 6th Battalion East Lancashires, who by this time, were serving in Mesopotamia.

The Mesopotamian Campaign

The campaign in Mesopotamia, part of the Ottoman Empire, had begun in 1914, with the objective to secure the supply of oil from the recently developed oil fields in Persia. The oil pipeline ran along the Shatt al-Arab waterway southward to the refineries on the island of Abadan. Abadan provided direct access to the sea. The Shatt al-Arab marked the boundary between the Persian and Ottoman empires, as it does between Iran and Iraq today.

The day after the Ottoman Empire declared war, on 5th November 1914, a force of regular British and Indian battalions, sent from India, landed close to the entrance of the Shatt, and was reinforced shortly afterward. After a series of swift defeats, Ottoman forces abandoned the city, and Basra was taken on 21st November 1914. At this point, the immediate objective of protecting the oil facilities had been achieved; however, a limited advance was authorised to Qurna, fifty miles further up the Tigris, at the junction of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which would put the whole length of the Shatt al-Arab under British control. Qurna was taken on 9th December, with relatively few casualties.

The "Indian Expeditionary Force ‘D'", as it was called, was reinforced over the next few months, and was able to defeat the eventual Ottoman counter-attack in April 1915, at the Battle of Shaiba, in which a large Ottoman force attempted to retake Basra, via the Euphrates river, from the west. Whilst London attempted to keep the campaign confined to the limited objectives of securing the oil supply, the Indian Government wanted to achieve more - and the level of resistance so far encountered encouraged them to aim for the capture of Baghdad, notwithstanding the difficulty of operating in an area where it was only possible to transport supplies by boat.

The next target was therefore the town of Amara, nearly ninety miles north of Basra, which again was achieved with very few casualties - Ottoman forces once again withdrew and those in the town surrendered. Amara was taken on 4th June 1915.

After this, the British targeted Nasiriyya, on the Euphrates, to complete the conquest of the province of Basra. Bedouin soldiers serving with the Ottoman forces turned against them, seeing an opportunity to challenge Ottoman rule. But after heavy fighting, Nasiriyya fell on 24th July 1915.

At this point, the Indian Government argued strongly for the occupation of Kut, and for extra troops, but for the British Government, the priority was the Western Front. Indian forces could not be made available - the existing forces in Mesopotamia, though reduced by the campaign so far, could not be reinforced. Nonetheless the advance continued; reconnaissance convinced General Sir Charles Townshend, commanding IEF "D", that Kut could be taken. But Ottoman defensive positions seven miles downstream from Kut, at al-Sinn, were strongly held, and overcoming them involved heavy casualties. However, once again, on 29th September 1915, Ottoman forces staged a strategic retreat, and withdrew, leaving the town to be taken by the British.

On 21st October 1915, the Dardanelles Committee considered the options. Victory in Baghdad was a tempting prospect, especially as the Committee confronted the failure in Gallipoli. On the other hand, whilst the city might be taken, it could not be held without significant reinforcements. In the end, no conclusion was reached, but the Secretary of State for India, Austen Chamberlain, was persuaded by the more bullish members of the Committee to authorise the occupation of Baghdad. Two Indian divisions were promised to be sent from France to Mesopotamia "as soon as possible'.

In the meantime, however, Ottoman forces were reinforced, and new field commanders appointed. British forces were now significantly outnumbered by Ottoman forces defending Baghdad, and strong defences had been constructed to the south of the city around the Arch of Ctesiphon (a sixth century monument). Due to limitations on reconnaissance capability after aeroplane losses, the British were unaware of the full extent of these changes and preparations, and, in any case, their previous experience gave them a high degree of confidence that they could overcome superior numbers.

At the Battle of Ctesiphon, on 22nd November 1915, the IEF ‘D' met stiff resistance from Ottoman forces. They took the first line of Ottoman defences, but could get no further. Casualties were extremely heavy; there were no reserves; advance was not possible, and neither could the position be held, in the open desert. After three days, Sir Charles Townshend withdrew to Kut. Conditions were appalling - transport was completely inadequate, and casualty evacuation completely broke down.

Townshend accepted that a siege was inevitable, but reinforcements were due to arrive in January, and he was confident that they would be able to relieve him. Supplies were assessed to be sufficient for three months, and he did not expect the siege to last anything like that long. After an Ottoman attack on Kut on Christmas Eve, however, causing heavy casualties on both sides, he was less sanguine, and began to press for swift action from the relieving force.

At this point, additional British forces began to arrive in the Mesopotamian theatre, made available by the end of the Gallipoli campaign. But the end of the Gallipoli campaign had also freed two experienced and disciplined Ottoman divisions for Mesopotamia. As time passed, the besieging army grew stronger, whilst the garrison grew weaker. There was thus considerable pressure to attempt to mount the relief of Kut, even though numbers were less than sufficient to ensure superiority. So several attempts were made, but all failed.

The 6th Battalion East Lancashires arrived in Mesopotamia from Gallipoli, by way of a month in Egypt, in March 1916, as as part of the 38th Brigade, 13th Division. These fresh troops of the 13th Division, together with the 7th Indian Division, were then used in a final series of attacks in April on the Ottoman positions around Kut. These too failed. The garrison surrendered on 29th April 1916 and five generals, 400 officers and nearly 13,000 men were taken prisoner; this was the British army's worst recorded surrender. Although officers and Indian Muslim men were well treated, British and other Indian soldiers were not. Of British other ranks taken into captivity in Kut, more than 1,700 died; figures for Indian other ranks are less precise, but no fewer than 2,500 died.

As Peter Hart says:

The consequences of hubris could not have been clearer ... [the campaign] was fought with insufficient troops and indadequate logistical arrangements; a campaign which ignored the unique terrain characteristics of the region and was underpinned by the presumption that the Turks were not capable of serious opposition.

As in Gallipoli, Britain had been defeated by the Ottoman Army; but, unlike Gallipoli, withdrawal was not an option - the future of the Empire in India and the Middle East was now perceived to be at stake. A new commander was appointed for what was now called the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force, Lt Gen Sir Stanley Maude. The entire transport and supply system was reorganised - new port facilities were established at Basra, reinforcement camps were built, proper military hospitals established, railways and roads were built, and military supplies flooded in, including artillery and aircraft. The four divisions were brought fully up to strength, totalling some 160,000 men.

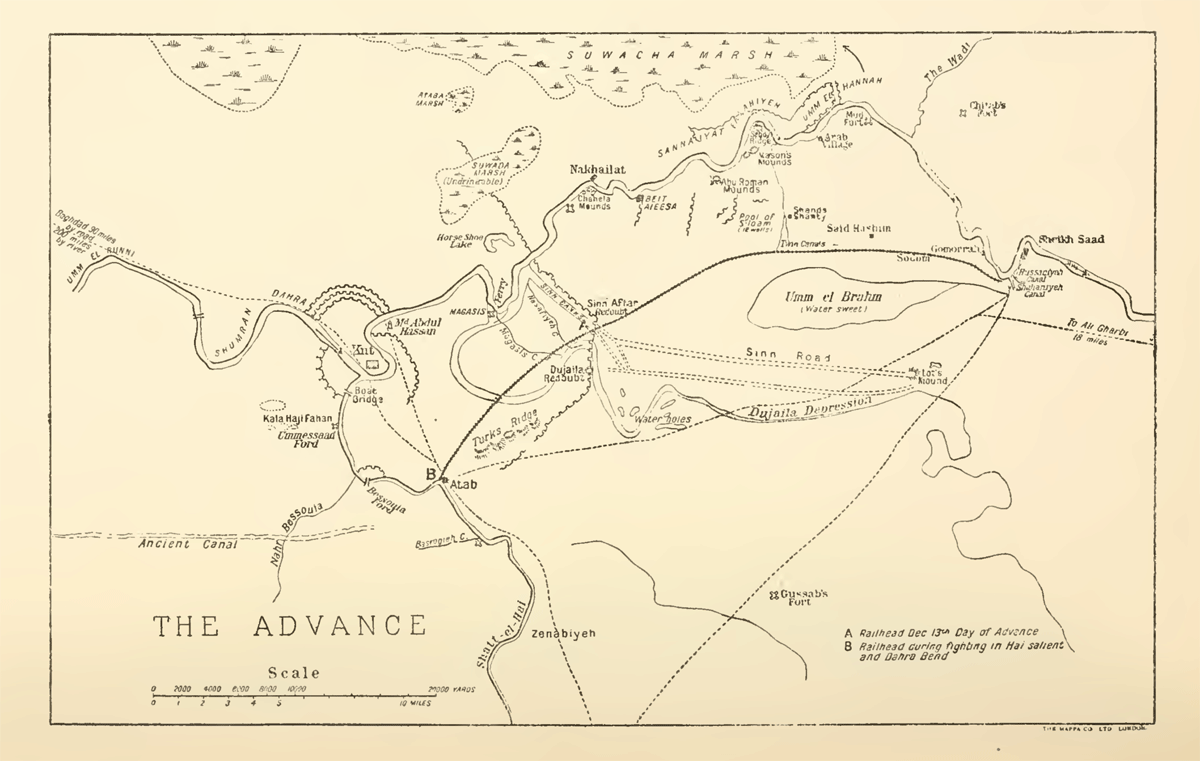

Amongst those arriving to reinforce 6th Battalion East Lancashires was Lewis. The Battalion War Diary records that he joined on 8th December 1916, at Sheikh Sa'ad, along with three other officers and 72 other ranks, just five days before General Maude finally began his carefully planned move to recover Kut, and before Lewis found himself in action for the first time. According to Eugene Rogan, General Maude was superstitious - he "believed 13 was his lucky number and had decided to launch his offensive on 13th December with the 13th Division in the vanguard".

Thus, the third battle for Kut opened on 13th December 1916. The campaign went on for two months along a twenty-mile front to the east and south of Kut. To the north and east, Ottoman defences exploited the meanders of the Tigris; to the south, a strong defensive position had been constructed around the point at which the Shatt al-Hayy waterway, running north-south to the Euprates at Nasiriyya, joined the Tigris.

The 6th Bn East Lancs moved forward initially on the east bank of the Shatt al-Hayy. By 17th December, they were holding a position either side of the Hayy, south of Kut, where they remained for some time. Despite the extensive investment in improving logistics, conditions were far from easy. On 28th December, there was a heavy rain storm which flooded the low ground and entered the trench they were holding. Barricades were erected and the water pumped out. Food supplies in tins "proved most unsatisfactory in majority of cases being by no means air tight"; rifle oil was scarce; and fuel "extremely deficient"; they were also short of drinking water for the first few days. However, waterproof capes previously issued were of great value, as the rain continued; proper washing facilities behind the lines meant that overall, health remained reasonably good.

On 25th January 1917, 40th and 39th Brigades attacked Ottoman positions at the Hayy bridge-head, 40th Brigade on the east bank and 39th Brigade on the west. The 39th Brigade's attack failed and there were heavy casualties; but the following day, 14th Division, relieving 13th Division, retook the line. The 38th Brigade had been in reserve during this action; on 28th January, they occupied the first and second line enemy positions which had been taken on the east bank of the Hayy, from the Tigris river on the right, to join 40th Brigade on the left. Though 6th East Lancs had not taken part in the attack, three officers were wounded, one of whom died, and six men were killed, with 41 wounded, four of whom died of their wounds. During the month, and notwithstanding the improvements in supplying and maintaining basic requirements, the Battalion also lost 34 sick.

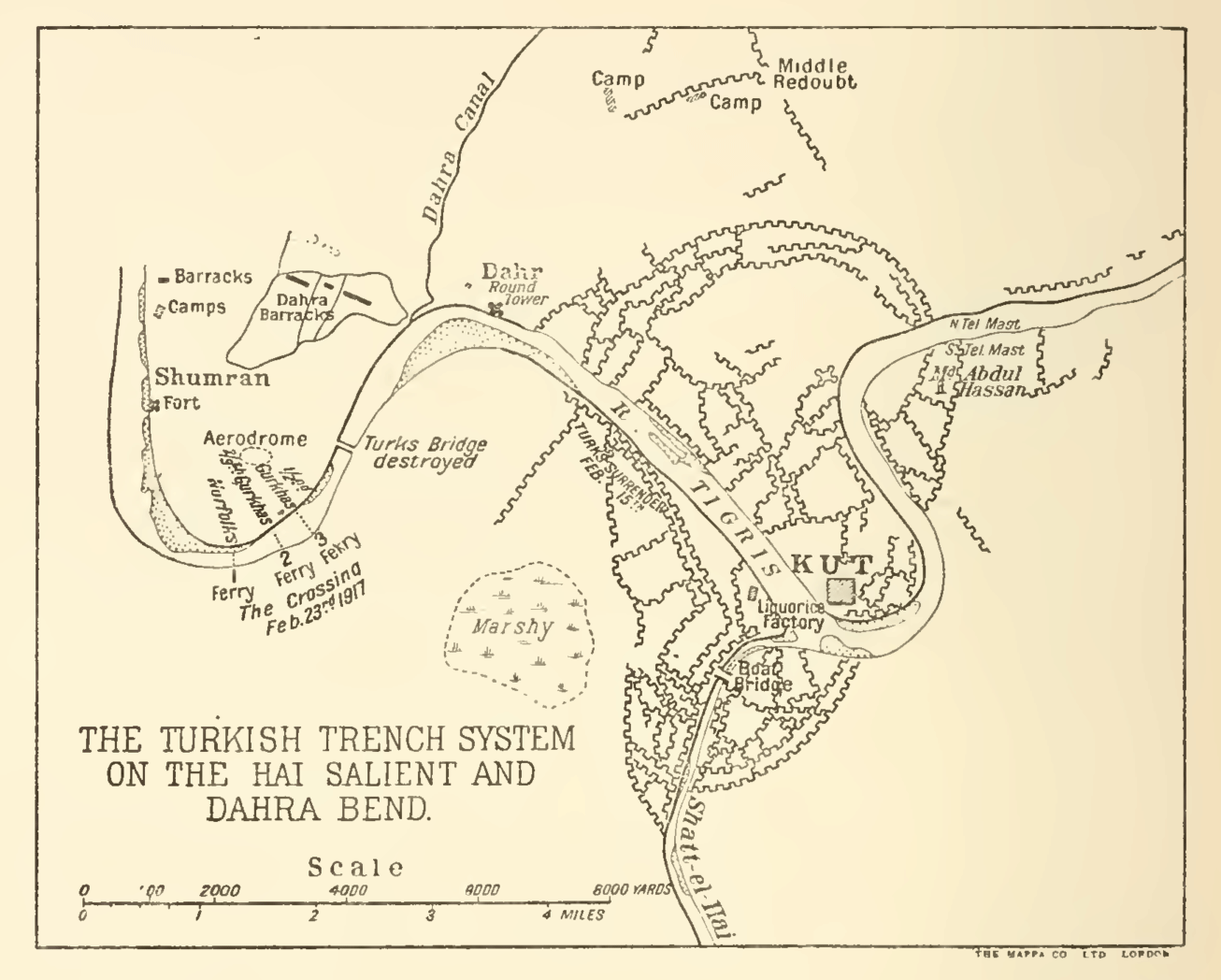

On 1st February, 37th Brigade attacked third line enemy positions on the west bank, with 40th Brigade once again attacking on the east. Again, the attack on the east was successful, but the positions on the west proved harder - they were more strongly fortified and Ottoman resistance was very determined. A further attack on February 3rd succeeded in taking the position. Meanwhile, 38th Brigade had followed 39th and 40th Brigades across the Hayy, as Divisional reserve. Very gradually the attack was pressed forward. The loop of the Tigris river north-west of Kut, called the Dahra Bend, had to be cleared; on 15th February, the Loyal North Lancs took a position known as "the Ruins", and 40th Brigade, with the East Lancs in 1st reserve behind them, "assaulted the enemy's right centre with complete success" (though not without casualties). Many Ottoman troops surrendered, and the Dahra Bend was taken.

As very heavy rain once again flooded camps, roads and rivers, making transport "almost impossible" the 38th Brigade went into camp at Bassouia, preparing for the next stage of the attack, which came on 23rd February. In a very carefully planned operation, involving the creation of three ferry points, the 14th Division successfully secured the crossing of the Tigris north of Kut at Shumran. On 24th February, the 6th East Lancs crossed behind them, and consolidated the crossing point whilst 14th Division moved forward, to Dahra Barracks, north of Kut. Meanwhile, diversionary attacks took place at Sannaiyat, at the other end of the British front, and near Kut itself.

As the British crossed the river, the Ottoman commanders realised their position was untenable, and an immediate retreat was ordered from all positions held on the north bank of the Tigris. The British once again entered Kut, on 25th February 1917.

However, the Ottoman retreat was orderly and effective, and protected by rearguard action. On 25th February, as the 6th East Lancs formed the advance guard to the division along the road towards Sheikh Jaad, Ottoman forces were discovered in a position "along nullah north and south from river". The Battalion War Diary describes the action briefly:

N Lancs on left E Lancs centre and Kings Own on right develop attack under heavy shrapnel fire, E Lancs getting to distance about 600 yards nullah. N Lancs sweeping along river flank with right 300 yds in rear our left and left slightly in front. KO on right 400 yards in rear. Line joined up with N Lancs and KO and partially consolidated. Fairly heavy casualties suffered, 5 officers wounded, 14 OR killed, 3 missing, 96 wounded. At dark Turks withdraw and at 6am Brigade pushed on to Sheikh Jaad and subsequently to Bghailah.

But Lewis did not see whatever Bghailah had to offer, for he was one of the five officers wounded in this attack. It is a measure of the improved handling of casualties by then in place in Mesopotamia that Lewis' name appeared as "wounded" in a casualty list published in England less than three weeks later, on 15th March 1917. He was treated in theatre, and was able to rejoin the Battalion in a little over a month.

By the time he rejoined, sometime between 20th-23rd April (the War Diary gives only a date range) Baghdad had also fallen, on 11th March 1917. Again, Ottoman commanders recognised that the city could not be held against the superior numbers and firepower of the British, and evacuated their forces.

However, now that the fabled city of the east had been taken, it had to be held. There were four objectives: to continue the pursuit of the retreating Ottoman army up the Tigris; to prevent them linking up with Ottoman forces now falling back before the Russians to the north; to capture the railhead at Samarrah; and to secure various dams along the Tigris and Euphrates north of Baghdad, so that the British army was not flooded out, or marooned on an island isolated from all supplies. So the fighting did not stop.

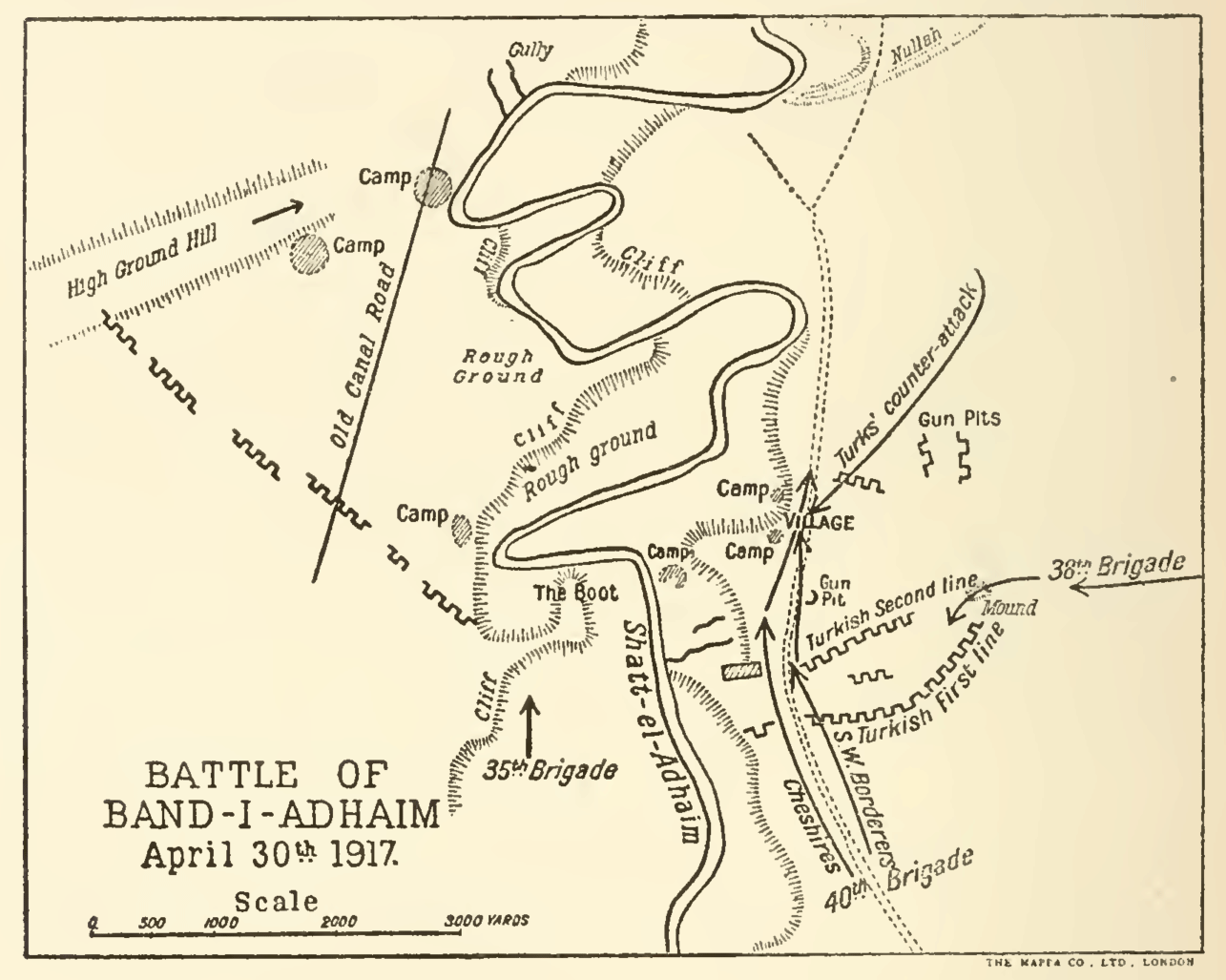

By 20th April the 38th Brigade, including the 6th East Lancs, had crossed the Shatt al-Adhaim, a tributary of the Tigris north of Baghdad. Ottoman forces were advancing down the river towards the Tigris, to prevent the capture of Samarrah, and had taken up a position at Band-i-Adhaim, where the high ground of the river banks jutted out forming the shape of a boot. "The Boot" had been fortified, as had the village.

The 38th Brigade attacked on the right, as a diversion for the main attack from the 40th Brigade in the centre. The East Lancs were in the centre of the brigade front, the Kings Own on the right, the South Lancs on the left, and the Loyal North Lancs in reserve. The 6th East Lancs War Diary describes, again briefly, what happened:

At 5am attack commenced, first objective reached with very little loss, here Brigade was met by heavy rifle and machine gun fire which held them in check, during the day the Brigade was under artillery, rifle [and] machine gun fire which made reorganisation practically impossible, so position was consolidated ... 6pm East Lancs forming part of picquet line with 40th Brigade on our left, remainder 38th Brigade less South Lancs on our right, South Lancs in reserve.

The War Diary also notes that during these operations two officers were killed, 2nd Lt R E Dear and 2nd Lt H H Billingsley, who had both joined the same day in December 1916 as Lewis. Five officers were wounded, one of whom was Lewis. Amongst the men, 13 were killed and 68 were wounded; two were missing.

To the 38th Brigade's left, the 40th Brigade had taken the village, but then been enveloped by a sudden dust storm. An Ottoman counter-attack had been mounted, passing right in front of 38th Brigade, using the dust storm for cover, but had been defeated after heavy fighting when 40th Brigade was reinforced. The defences on "The Boot" were then attacked by British artillery and the remaining Ottoman forces withdrew.

This seems to have been the last of the fighting in which the 6th Bn East Lancs were involved in Mesopotamia, for several months. It was also the end of Lewis' fighting too. He was seriously wounded and taken back to Baghdad.

Even though fighting was still continuing to secure the city fully, Baghdad had already become the advanced base for the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force, with two stationary hospitals and three casualty clearing stations. But notwithstanding these medical facilities, Lewis did not recover.

Death

On 25th May 1917 the Dartmouth Chronicle reported the following news:

Badly wounded: We regret to hear that Second Lt Lewis G Bates, son of Mr George Bates of L'Esperance, Dartmouth, has been seriously wounded. This is the second occasion on which he has been wounded. He is at Baghdad, and further news is anxiously awaited.

In fact, Lewis had died the day before this news appeared in the newspaper. The following week, on 1st June 1917, the Chronicle reported:

Death of Second Lt Bates: We deeply regret to hear of the death of Second Lt Lewis G Bates, of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, eldest son of Mr and Mrs George Bates, of L'Esperance, South Town Dartmouth, which occurred in hospital at Baghdad on Saturday, as a result of wounds received in action on April 30th. He was only 21 years of age.

The family placed an announcement in the "Deaths" column:

Bates: Died in Baghdad, May 26th, from wounds received in action on April 30th, Lewis George Bates, Sec. Lieut. Royal Warwicks, aged 21, the dearly loved son of Mr and Mrs G E Bates, "L'Esperance", Dartmouth.

The date of death appears to have been wrongly printed in the newspaper. All other contemporary records state that Lewis died on 24th May 1917.

Lewis was buried in Baghdad North Gate War Cemetery. From Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, it would appear that, although the Graves Registration Report Form recorded the date of his death correctly, an error was made in the date of death engraved on the headstone, which was then perpetuated in the printed Cemetery Register and hence on the CWGC database, which records the year of death as 1916 instead of 1917.

Today, the Cemetery is in what the Commonwealth War Graves Commission describes as "a very sensitive area in the Waziriah Area of the Al-Russafa district of Baghdad ... whilst the current climate of political instability persists it is extremely challenging for the Commission to manage or maintain its cemeteries and memorials located within Iraq. A two volume Roll of Honour listing all casualties buried and commemorated in Iraq has been produced. These volumes are on display at the Commission's Head Office in Maidenhead and are available for the public to view".

Commemoration

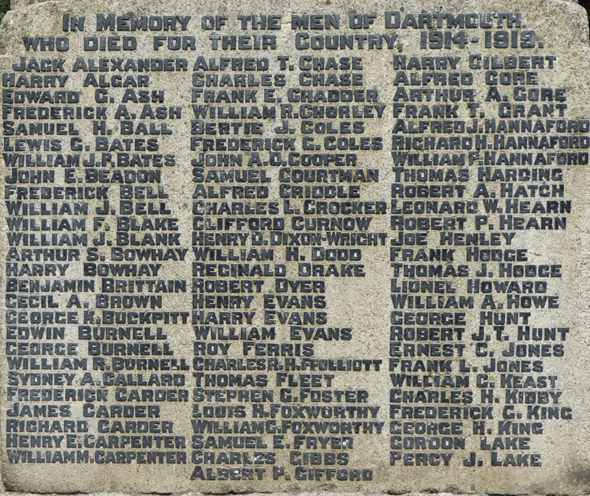

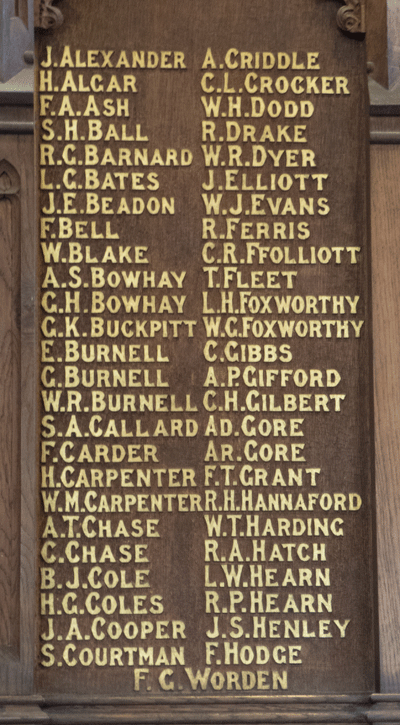

Lewis is commemorated in Dartmouth on the Town War Memorial and the St Saviours War Memorial Board.

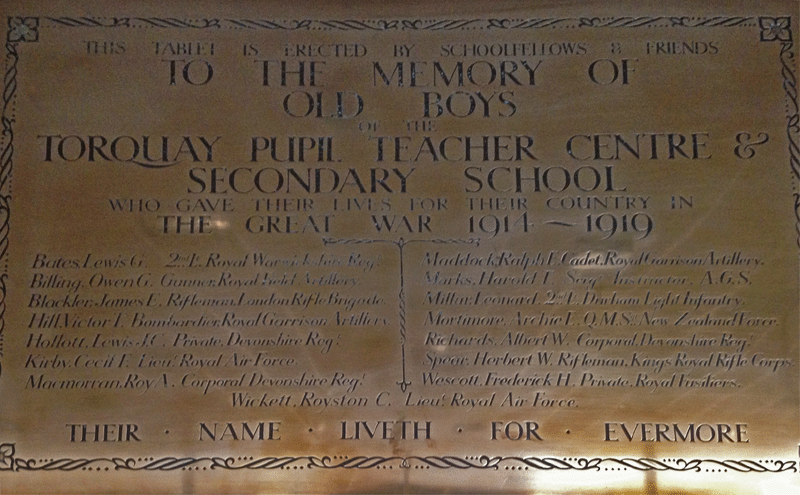

He is also commemorated on the Torquay Secondary School War Memorial, at Torquay Grammar School for Boys.

The Western Times reported the unveiling of this memorial on 19th June 1920:

School Memorial Tablet Unveiled at Torquay

On Thursday afternoon Mr C E Pitman (chairman of the Governors) unveiled a brass tablet placed in the main hall of the Torquay Secondary School, commemorating the sacrifice of sixteen old boys, who were killed in the war. A large company were present .... The service was conducted by Prebendary G H Statham and Rev J C Johnston, whilst the Principal (Mr W Jackson) read the inscription on the tablet:

This tablet is erected by the schoolfellows and friends to the memory of old boys of the Torquay Pupil Teachers Centre and the Secondary School, who gave their lives for their country in the great war 1914-19.

Their name liveth for evermore.

The boys' names were then listed in the paper.

Sources

War Diary of the 6th Battalion East Lancashire Regiment, 38th Infantry Brigade, 13th (Western) Division, February 1916-March 1919 is available for download from the National Archives, fee payable, reference WO 95/5156/1

Maps from The Long Road to Baghdad, Volume II, by Edmund Candler, publ 1919 Boston & New York, accessed at archive.org

The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East 1914-1920, by Eugene Rogan, publ Penguin Random House 2015

The Great War 1914-1918 by Peter Hart, publ Profile Books, 2014

The 1/7th and 2/7th (Cyclist) Battalions, The Devonshire Regiment

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Bates |

| Forenames: | Lewis George |

| Rank: | 2nd Lieutenant |

| Service Number: | |

| Military Unit: | Royal Warwickshire Regiment, attached 6th Bn East Lancashire Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 24 May 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 21 |

| Cause of Death: | died of wounds |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of Band-i-Adhaim |

| Place of Death: | Baghdad Hospital |

| Place of Burial: | Baghdad |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Torquay Secondary School |