Alfred Charles Partridge

Family

Alfred Charles Partridge was born in Dartmouth on 5th October 1883 and baptised at St Saviours on 10th February 1884. He was the youngest son of Alfred John Partridge and his wife, Harriet Selina Thorn.

Alfred John Partridge came originally from the village of Cheriton Bishop, on the northern borders of Dartmoor. When he first arrived in Dartmouth is not known, but on 12th April 1868 at St Saviours he married Harriet Selina Thorn. At that time he was working as an Ostler.

Harriet was the daughter of Thomas Thorn, a sailor, and his wife Harriet Lang. We have not been able to trace how and exactly when her father died, but according to 1851 Census records, her mother, Harriet Thorn (senior) was a widow by the time her daughter was two; she also had a son, Thomas Edward, two years older. Harriet Lang's father, Edward Lang, had been the Sexton at St Saviours and Harriet continued to work in the church; the 1851 and 1861 Censuses record her as "Sextoness", living close to the church in Church Street. By the time of the 1861 Census she was also taking in several lodgers to help make ends meet. Her life was far from easy - later Census records state that Thomas Edward, her son, had been blind from the age of nine.

Perhaps because of this, when Alfred and Harriet married, they did not set up house on their own but made their home with Harriet's mother and brother. At the time of the 1871 Census, the family lived, as the description puts it, "near the church". Their first child, Harriet Ann, was born in 1869, followed by Jessie Louisa, two months old at the Census, in 1871. (For Jessie Louisa, see the story of her son, William Rowe). Alfred was shown in the Census as an Ostler but he also did labouring work.

Alfred and Harriet's family continued to grow. A third daughter, Charlotte Selina, was born in 1873, followed by two sons, William in 1875 and Samuel Henry in 1877. The baptism records indicate that Alfred now worked mostly as a gardener. Alice Maud Mary was born in 1879; all the children were baptised nearby in St Saviours, where their grandmother Harriet still worked. In 1881, they still lived "near the church", with grandmother Harriet and her son, Thomas. Alfred was born in 1883, the last of the family.

Harriet Thorn died on 18th March 1890, at Higher Street. The notice of her death in the Dartmouth Chronicle described her as "many years butt-woman at St Saviour's Church" (a "butt-woman" was a female verger or pew-opener, and also kept the interior of the church clean, including beating the butts, or hassocks.) By this time, however, the family no longer lived right by the church; indeed, the Census of 1891 recorded Alfred and Harriet at two separate addresses, though fairly close to each other in the centre of Dartmouth. Alfred lived in Oxford Slip with the two youngest children, Samuel Henry and Alfred Charles, the latter by now aged eight; Harriet lived in Higher Street with her brother, Thomas, her daughters Annie, Jessie, Charlotte, and Alice, and her son William, and two grandchildren, William Samuel Partridge, aged 4, and Florence Maud Partridge, aged 3. She worked as a "housekeeper"; and her three older daughters also worked in domestic service. Harriet's brother, Thomas, retained the family's close connection with St Saviours - he was employed as a bellringer.

When Alfred Charles was twelve, his mother, Harriet, died, aged only 46. Charlotte and Jessie both married in the same year, 1895; Harriet Ann, known as Annie, married in 1899. Charlotte and Annie between them provided homes for their father and brothers and sisters. The 1901 Census recorded Alfred John and his son William living with Annie and her son Percy (and two boarders) in Lower Street. Alfred John continued to work as a gardener, while William worked as a labourer. Not far away, also in Lower Street, were Samuel and Alice (known as Maud), living with Charlotte and her husband John Finch. Samuel and John both worked as coal-lumpers; Maud was in domestic service. Alfred Charles, now aged 17, was accommodated a little out of town. He was one of seven farm servants working for farmer Sampson Channon at Little Dartmouth farm, along with Charles Chase, who is also on our database, and his brother Sidney.

Next door but two to the Finch household was the family of George Henry Perring and his wife Susan, and three of their children, Jessie Evelyn, aged 18, Samuel George, aged nine, and Elsie Evelyn, aged 6. George worked as a labourer and Susan took in washing. Jessie worked in domestic service. George had come to Dartmouth from Stoke Fleming and Susan from Dittisham but they had lived in Dartmouth for some time and Jessie was born and brought up there; Jessie and Alfred Charles may have known each other well before their families lived close by each other.

Jessie and Alfred Charles married at St Saviours on 13th May 1906. Both gave Hanover Square as their residence; Alfred Charles worked as a groom (he also described his father's occupation as "groom" rather than gardener). Their first child, Winifred May, was baptised at St Saviours, on 10th January 1907; but very sadly she died aged only four months, and was buried at Longcross on 26th March 1907. By the time of the birth of their second child, a boy, Alfred Charles was working as a Waggoner, and the family had moved to Above Town. Frederick Charles was born on 6th August 1908 and baptised at St Saviours on 17th September of that year.

Alfred John died in 1908 and the next child was named for him - Alfred John (junior) was born on 20th November 1910 and baptised at St Saviours on 5th January 1911. By this time, the family had moved back to Hanover Square, and were recorded there in the 1911 Census. Next door was Jessie's mother Susan Perring, now widowed, and her brother Samuel. Alfred Charles, recorded on the form as Charles, was a Grocer's Waggoner.

Jessie and Alfred Charles' fourth child was named for Jessie's father, George Henry Partridge. He was born on 19th June 1912 and baptised at St Saviours on 17th October 1912. By this time, the family had moved from Hanover Square to Browns Hill. Finally, on 6th April 1914, twin girls were born, Elsie and Viola Ethel. Elsie died soon after her birth but Viola Ethel was baptised at St Saviours on 20th August 1914, only a couple of weeks after the outbreak of war. She died aged two, and was buried at Longcross on 27th November 1916; by that time, Alfred Charles had been in the Army for two years. Whether he was able to get leave to return to Dartmouth to be with Jessie and his other children is not known.

Service

Alfred Charles' individual service records have not survived, but the Devonshire Regiment's Medal Rolls show that he first joined the 8th Battalion and went with them to France, disembarking there on 25th July 1915. His service number was 14824; that of his brother, Samuel Henry, was 14823, suggesting that they joined up together. Samuel's discharge papers have survived, showing that he served with the 3rd Battalion of the Devon Regiment (the training and reserve battalion for the regulars) in England, until he was discharged no longer physically fit, on 7th July 1916. Although the papers do not give his date of enlistment, he had served for one year and 216 days. This suggests that he and Alfred Charles joined up around the end of November 1914 or early December. Number 14825 enlisted on 5th December 1914.

Records show that Alfred Charles was serving in the 1st Battalion of the Devon Regiment by the time of his death, but so far we have not been able to identify when, much less why, he transferred from the 8th Battalion to the 1st Battalion. Both Battalions included several men from Dartmouth - for the experiences of the 8th Battalion to 28th March 1917, see the stories of Andrew Prettyjohn, William Marks Carpenter and Harry Bowhay. For the experiences of the 1st Battalion to 1st January 1917, see the stories of George Peters and Cyril Privett.

The 1st Battalion's War Diary records large numbers of reinforcements arriving during the period from October 1916 to February 1917, and smaller parties contined to arrive up to the day before the action on 23rd April 1917. Unfortunately, it says nothing about these men's previous units. Several large groups, for whom special training arrangements were made, may have been new recruits, but there were also many small parties arriving during this period too.

At the beginning of 1917, the 1st Battalion was in the Cuinchy sector, where it remained until the middle of March. The situation was quiet - on many days, the Battalion's War Diary observes that "nothing of note occurred". The tempo of events did not begin to quicken until the very end of their stay in the sector - a trench raid was mounted on the night of 15th March 1917 but "owing to a second line of wire being found beyond that blown up by an ammonal tube, the party was unable to enter the enemy trenches". There were seven casualties. Two days later, in apparent retaliation, the 1st Devons' stretch of the front line, support lines and communications trenches, was heavily bombarded and they sustained 17 casualties. That day, 17th March, they were relieved and went into billets at Raimbert, west of Bethune, where they remained, resting, for three weeks.

While they rested, the Germans had retreated to the Hindenburg Line and the planning of the Allies' spring offensive had been underway. For the background to the Battle of Arras, which began on 9th April 1917, see the story of Cyril Stafford.

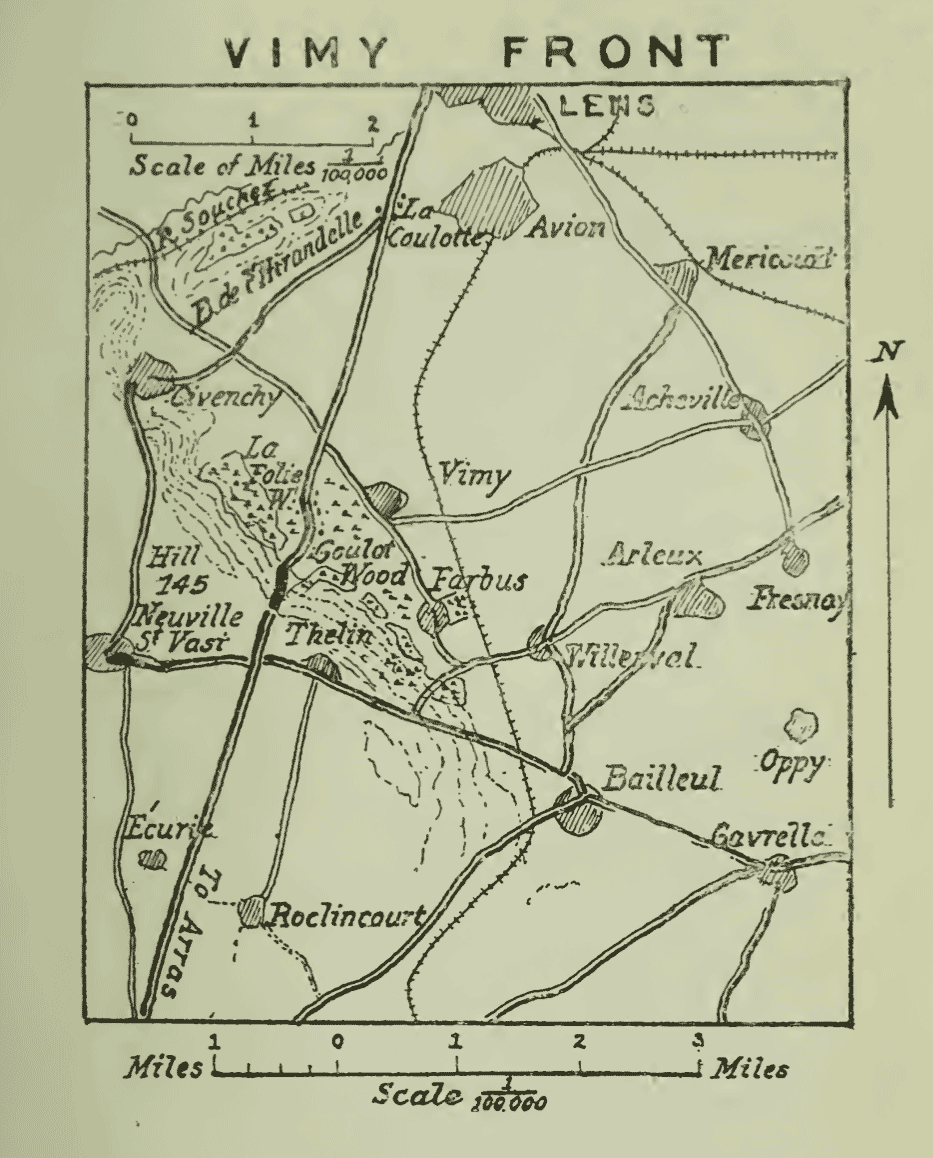

The plans for the battle put the 5th Division, including 1st Battalion, in reserve, so the Devons were not brought down to the area until close to the date of the initial attack. The Devons were in any case not that far away. On 7th April, they began their march southward, arriving that evening in Houdain and by the end of the following day, at their destination of Villers-au-Bois, north-west of Arras. The role of 5th Division was to support the attack of the Canadian Corps on the Vimy Ridge, but so successful was the attack that only one of the Division's brigades was required to move up. The 1st Devons remained in readiness in Villers-au-Bois, but were not called forward.

They thus came into the continuing action around Arras on 13th April, to take over the far left, or north, of the new front line. They arrived at the hill known as "The Pimple", at the northern end of Vimy Ridge, at about 7pm. As they got there, however, they found that the enemy had evacuated the village of Givenchy-en-Gohelle, so they were able to advance further forward, to a position east of the village.

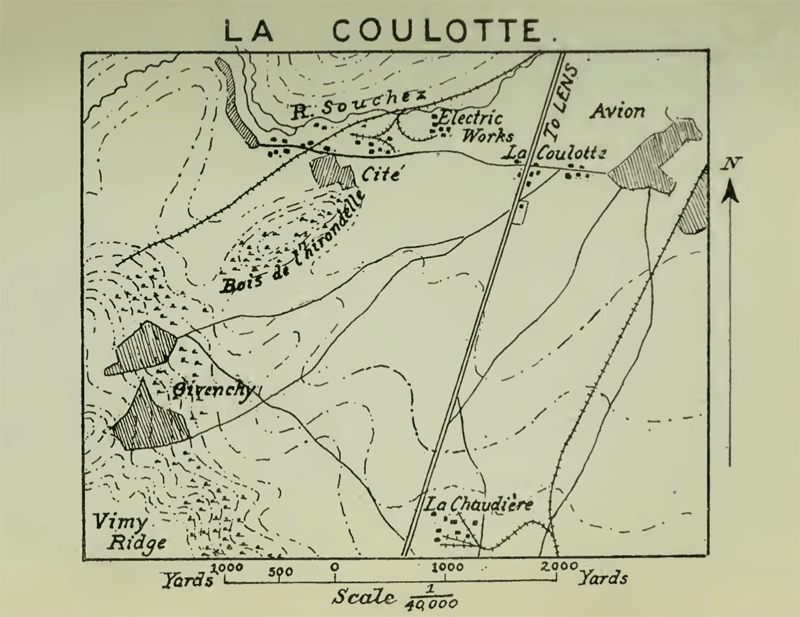

But as they continued to advance the following day, it became clear that the line to which the Germans had now retired was strongly fortified. It ran south-east from an electricity generating station close to the Souchez river, along a railway embankment through La Coulotte, a village south of Lens, to the village of Avion (both now in effect part of the suburbs of Lens). The Divisional History describes the terrain:

The left flank of our position rested on the Souchez River, and the right on the Arras-Lens road; immediately south of the Souchez River was the wooded spur of the Bois de L'Hirondelle, a locality subjected to very severe shelling by the enemy's artillery. With the exception of this, the ground behind our lines was open and practically flat for a space of 2000 yards, to the point where the Vimy heights rose from the plain.

The German position was formidable, protected with three deep belts of barbed-wire entanglement; opposite the 95th Brigade was a strongly fortified railway embankment and the buildings of the Electricity Works, transformed by concrete and steel into a veritable fortress, whilst opposite the 15th Brigade were the mine buildings, factory and houses of La Coulotte, similarly strengthened and fortified. Between the two ran a double trench-line, with numerous shell-proof dugouts and machine gun emplacements.

As they advanced, the Devons came under heavy rifle and machine gun fire and, without artillery support, could go no further. That day, one officer and six men were killed in action, and a second officer and 32 men were wounded; while they held their position over the next five days, they were in continuing contact with the enemy and sustained a further sixty casualties.

Further, conditions generally were very difficult. According to the Regimental History:

The British bombardment had reduced the ground to a mass of shell holes and battered defences, tracks had to be made afresh, and ever since the attack blizzards and snow showers had been incessant. The strain, both on the transport and on the troops was, therefore, great. Only scanty supplies could reach the front line, and the week which the battalion spent in the advanced positions was extremely uncomfortable.

On 19th April, they were relieved for a brief but much-needed rest. While they had been in the line, there had been a pause overall in British operations around Arras, as the French offensive was launched further south. High hopes had been raised that a breakthrough would be quickly achieved, but although there was some early success, French casualties were extremely high. It soon became apparent that "breakthrough" was unlikely. This meant that British pressure at Arras needed to be maintained, and on 23rd April, despite misgivings at the highest level of the British command, a renewed offensive was launched east of Arras. For the "Second Battle of the Scarpe", in particular the attempt to take the village of Roeux, see the story of James Henry Moriarty.

The Battle of Arras: Attack on La Coulotte, 23rd April 1917

At the same time as the attack was launched east of Arras, First Army was committed to a subsidiary attack in the north, beyond the Vimy Ridge. 46th Division attacked north of the Souchez River, whilst 5th Division attacked, in effect, where they were already, between the River and the Vimy-Lens railway. The 95th Brigade attacked on the left of the Divisional front, with the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry on the left next to the river and the Devons on the right. To the right of the Devons was the 1st Bn Bedford Regiment, of the 15th Brigade. Because of the need to maintain pressure whilst the French offensive continued, there had been little time for preparation. In addition, weather and ground conditions had prevented enough heavy artillery being brought forward. Enemy artillery in rear were therefore relatively untouched; and the preliminary barrage was insufficient to deal with the strength of the defensive line which the Germans now held, as described above.

The attack went in at 4.45am. Many casualties were caused by the hostile barrage which caught the troops in their assembly positions - the 1st Devons War Diary observed that the "hurrying up of the attack [due to the need to maintain pressure at Arras] .... meant that it was impossible to either dig assembly trenches or put the taped assembly positions close enough up to the German wire, the result being that the Battalion had over 600 yards to go before reaching the enemy's front line, and in so doing was caught in the hostile barrage, which they would largely have escaped had they been able to jump off nearer the first enemy trench".

The British barrage had made little impact on the wire, which was mostly intact. Where gaps had been made, some officers and men got through, but those who did lost touch with each other, and the attack was split up. Although the enemy's first line was reached, and some prisoners were taken, the Germans then counter-attacked, apparently encouraged when they saw the difficulties caused by the wire. The 1st Devons War Diary states that:

The enemy were inclined to surrender at the very first, but as soon as they saw our troops in difficulties with the wire they gained confidence and opened heavy MG and rifle fire on the attackers. Snipers from houses and previously prepared loopholes which had not been damaged by artillery fire were particularly active all day and caused many casualties.

Although those who had succeeded in taking sections of the first line of German trenches fought hard, destroying several machine guns, by 10am only two officers were unhit, and those holding the positions they had taken were subject to attacks on both flanks. Eventually the survivors were forced to fall back, or risk being overwhelmed completely. By 3pm those remaining were digging in some way in front of their starting point, to be joined as night fell by those who had fallen close to the wire but were able to get back under cover of darkness. At 9pm the Battalion withdrew to the original jumping off position and two hours later, was relieved by the 1st Bn East Surreys.

The attack had been a costly failure and, as indicated above, the Battalion's War Diary offers caustic comment on the lack of proper preparation. Casualties were heavy, especially when added to those incurred during 13th- 19th April. The War Diary gives the following figures for the action on 23rd April 1917:

All the Division's battalions suffered similarly: the 15th Brigade lost 36 officers and 709 other ranks killed and wounded; the 95th Brigade (including the 1st Devons), 30 officers and 850 other ranks.

Death

The Divisional History observes that the casualty evacuation routes were "an extremely long and difficult carry" and that "both routes were heavily shelled and there were many casualties", but that "all the wounded were brought back expeditiously". Notwithstanding the final point, further casualties amongst the wounded may be the explanation for uncertainty immediately after the action about what had happened to Alfred Charles, and indeed, others from the Battalion. His name first appeared in a list of wounded from the Devon Regiment published in a casualty list in the Western Times on 28th and 29th May 1917, along with another Dartmouth man, William Elliot Stone. The casualty list also included names of men from the Regiment who had been killed, and, although of course the list did not say so, these men were almost all from the 1st Battalion, and their dates of death (as we now know) were almost all 23rd April 1917. At that stage, only two names from the Regiment were listed as "missing".

On 9th June 1917 a further list was published in the Western Times of Devon Regiment men declared as "missing" - again, the vast majority of these were from the 1st Battalion and subsequent records show them as having been killed in action (or presumed to have been) on 23rd April 1917. One of these was a third Dartmouth man, Charles Tucker.

On 15th June, a third list was published in the Western Times listing several names from the Devon Regiment, including both Alfred Charles Partridge and William Elliott Stone, as "previously reported wounded, now reported wounded and missing".

It seems that Alfred Charles' body was never found (or if it was found, was never identified). The Soldiers' Effects Register records his date of death as "presumed 23rd April 1917" and the Medal Rolls also similarly record "death regarded 23rd April 1917".

Commemoration

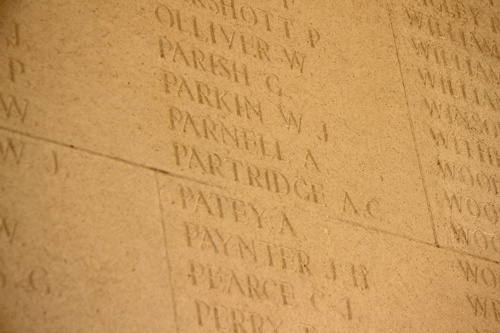

Alfred is thus commemorated in France on the Arras Memorial, which records the names of almost 35,000 men dying in the Arras sector between spring 1916 and early August 1918, who have no known grave.

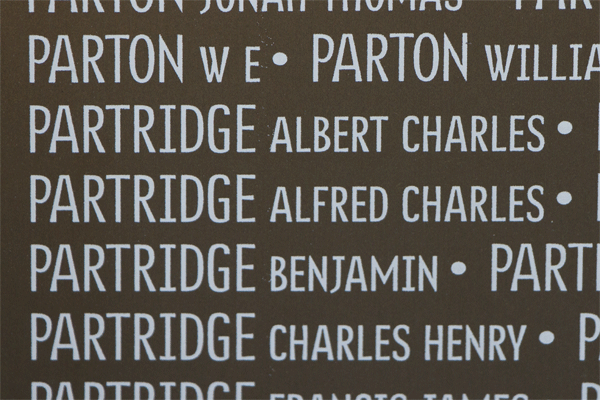

As one of the 579,206 casualties in the region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Charles is also commemorated on the new memorial at Notre Dame de Lorette, "The Ring of Memory".

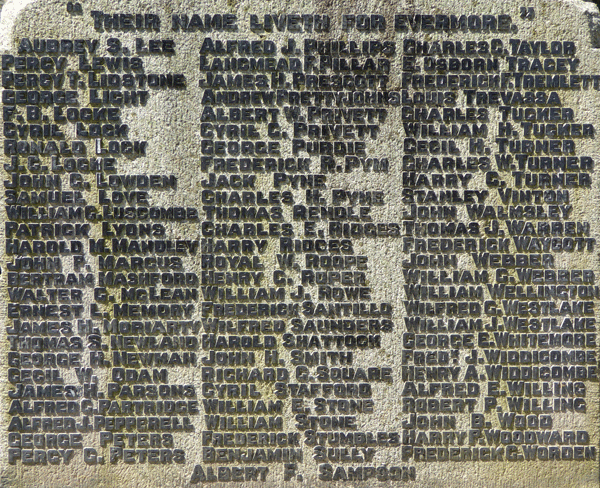

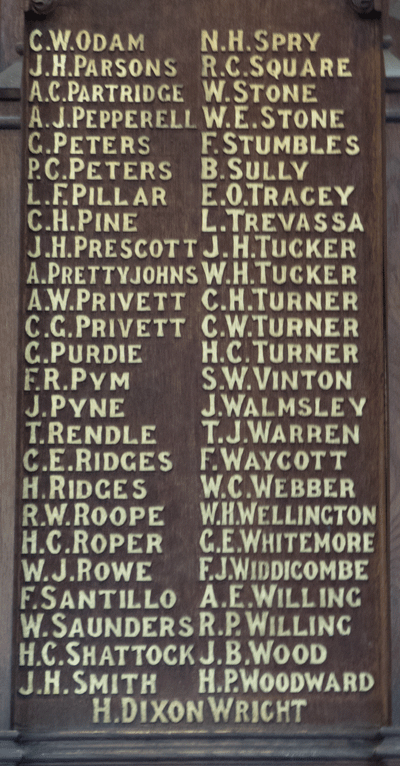

In Dartmouth, Alfred is commemorated on the Town War Memorial and the St Saviours War Memorial Board.

Sources

War Diary of the 1st Battalion Devonshire Regiment January 1916 - November 1917 available from the National Archives, fee payable for download, reference WO 95/1579/3

The Devonshire Regiment 1914-1918, compiled by C T Atkinson, publ. 1926, Exeter and London

The Fifth Division in the Great War, by Brig Gen A H Hussey CB CMG and Major D S Inman, publ. 1921, London, accessible online from archive.org

The Arras Offensive 9th April - 16th June 1917

The Battle of Arras: an Overview

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Partridge |

| Forenames: | Alfred Charles |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 14824 |

| Military Unit: | 1st Bn Devonshire Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 23 Apr 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 33 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of Arras |

| Place of Death: | Near La Coulotte, France |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Arras Memorial France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Not Known |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | "The Ring of Memory" at Notre Dame de Lorette |