Henry Chard Roper

Family

Henry Chard Roper was born in Dartmouth on 18th June 1879. He was the second son of Robert Roper and Harriet Wyatt. Robert came from East Allington, where his father, also Robert Roper, was a shoemaker. Robert (junior) also became a shoemaker - the 1871 Census recorded him, aged 15, already working in this trade, quite likely alongside his father. Sadly, Robert (senior) died later that year; it seems that Robert (junior) then moved to Dartmouth to find work.

Harriett was born in Blackawton. Her father, James Wyatt, was a farm labourer; by the time of the 1861 Census, Harriet and her family had moved to Dartmouth, where James worked as a labourer on Townstal Farm. Harriet, aged 19, worked in domestic service; by the time of the 1871 Census, she was working as a general servant for Miss Keturah Hingston, in Foss Street. It seems that Harriet and Robert met in Dartmouth. They married at St Clements, Townstal, on 17th January 1877.

Harriet and Robert's first child, William, was baptized at St Clements just under a year later, on 6th January 1878. At that time, Robert was working as a labourer, but by the time of Henry's birth eighteen months afterwards, he had returned to the shoemaking trade. Henry was baptized at St Clements on 10th August 1879. At the time of the 1881 Census, the family lived in Clarence Hill. A daughter, Annie Maria, was born on 3rd October of that year, and she too was baptized at St Clements, on 23rd October 1881.

By 1891, the family had moved to Cox's Steps, in Dartmouth, and James Wyatt, Harriett's widowed father, had come to live with them. Robert continued to work as a shoemaker, but neither William nor Henry went into their father's trade. The 1901 Census records that William became a ship joiner, presumably working in one of Dartmouth's shipbuilding firms, and Henry became a tailor. On 1st June 1901, William married Edith Warren, from North Huish, but very sadly he died only a few months later, on 20th March 1902, at Clarence Street, Dartmouth, "the beloved husband of Edith Roper, and dearly loved son of Robert and Harriet Roper".

On 7th June 1905, at St Clements Townstal, Henry married Mary Jane Randall. One of the two witnesses was his sister, Annie Maria, who herself married a few weeks later, also at St Clements. Mary Jane was the daughter of Augusta Cocker and John Randall, a blacksmith. She was born in Beesands and baptized at St Michael's, Stokenham (in the name of Mary Jane Randall Cocker) on 18th May 1879. From census records, it would seem that she was first brought up by her widowed grandmother, Charlotte Cocker (sometimes recorded as Crocker), in Stokenham, and then lived with her mother's brother Edwin and his family in Brixham, where she worked in domestic service.

From electoral registers, we know that Henry and Mary Jane lived first in South Town, and in 1910 moved to Lake Street. At the time of the 1911 Census, they lived in Mansard Cottages, Lake Street; Henry worked as a "tailor in [a] tailor's shop" - the Census does not record which one. Also living with them as a boarder was Ezra Thackeray, age 21, from Plymouth, who worked as an Assistant Superintendent for a Life Insurance business.

In 1913 they moved nearby to Mount Terrace, Ford, Victoria Road, and Henry was still recorded there in the 1915 Electoral Register.

Service

Like so many, Henry's service papers have not survived, but Soldiers Died in the Great War records that he was still living in Dartmouth at the time he enlisted. His entry on the Devonshire Regiment British War and Victory Medal Roll records that he first joined the 9th Battalion and then transferred to the 16th Battalion.

There is no date given for his arrival in any theatre of war on Henry's Medal Index Card, indicating that he did not go overseas until 1916. Surviving records for men with service numbers close to Henry's (26783) suggest that he may have attested late in 1915 under the Derby scheme, and been called up some time during the second week in June. This also matches the likely length of service suggested by the war gratuity paid to Henry after his death. One man, with the number 26774, was then posted to the 9th Battalion on 4th October 1916. If Henry's posting followed the same pattern, he will have joined the 9th Devons on the Somme.

The 9th Battalion included several men with Dartmouth connections. They had arrived in France on 28th July 1915, in time to fight at the Battle of Loos in September of that year, and on the first day of the Battle of the Somme (1st July 1916). For their experiences to that date, see the story of Robert Phillips Willing. For their later experiences on the Somme, see the story of Ernest Leonard Memory and Thomas Alfred Smith. It's possible that Henry may have been amongst the reinforcements joining in early November 1916.

No information has yet come to light to indicate when Henry may have transferred to the 16th Battalion. The Battalion was not formed until 4th January 1917 - see below - and drafts continued to arrive during the first few months of that year. Another Dartmouth man posted to the 16th Battalion, most probably at this time, was Benjamin Sully.

The 16th Battalion Devonshire Regiment

When Gallipoli was evacuated, several brigades of dismounted yeomanry (Territorial Force light cavalry) who had gone to Gallipoli as dismounted troops late in the campaign, had been transferred to Egypt. Among these was the 2nd South Western Mounted Brigade, composed of the Royal 1st Devon Yeomanry, the Royal North Devon Hussars, and the West Somerset Yeomanry. They then had a long spell of service as a dismounted unit in Western Egypt.

After the British defeat of Ottoman forces at the Battle of Ramani in August 1916, the defence of the Suez Canal was assured. With the fall of El Arish on the Mediterranean coast, a forward supply base was available for an assault on Turkish bases in Palestine. The dismounted Yeomanry were organized into a new Division - as the units were much smaller than an infantry battalion, they were mostly combined in pairs. The two Devon units were thus combined on 4th January 1917 to form the 16th (Devon Yeomanry) Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment (A and D Companies were formed from the 1st Devon Yeomanry, and B and C Companies from the North Devon Hussars). Also part of this reorganization was the 12th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry - see the story of Bertram Mashford. Together with other dismounted troops they joined the 229th Brigade of the 74th Division, in the Egypt Expeditionary Force, commanded by General Sir Archibald Murray.

In command was General Sir Archibald Murray. His first target was Gaza, but in his first attempt on 26th March 1917, he narrowly failed to take the town. However, his over-optimistic report appeared to offer the opportunity for significant success, so he was promised future reinforcements and ordered by the War Cabinet not just to continue with the attack on Gaza but to press on to Jerusalem and occupy the holy city.

After the first attempt on Gaza the town was heavily fortified by the Turks and defences strengthened. Notwithstanding the use of gas, and eight tanks (Mark I tanks by then considered obsolescent on the Western Front), the Second Battle of Gaza, fought on 19th April 1917, was a clear defeat for the British.

The 16th Devons had not taken part in either attempt on Gaza, being held in reserve. Sir Archibald Murray was soon replaced by General Sir Edmund Allenby, brought from the Western Front, and a period of reorganization, reinforcement and preparation began. At Atkinson puts it in his account of the Devonshire Regiment:

This repulse [at Gaza] was the governing factor in the fortunes of the 16th Devons for the next six months …[who] remained held up before Gaza. At first the Seventy Fourth Division held part of the line … and [the] extensive No Man's Land gave ample opportunities for patrol work … Early in July the Division went out of the line and spent two months in back areas, training … In September large working parties were called for to dig trenches in the forward area …

The conditions were difficult:

There was considerable sickness … the Scirocco blew frequently … flies, lice and scorpions all did their bit to add to the discomforts of existence, and at first, water was none too plentiful.

In the meantime, the success of Arab forces in taking Aqaba, on 6th July 1917 (the campaign so memorably depicted in "Lawrence of Arabia") meant that Ottoman forces in Syria and Palestine were now fighting on two fronts.

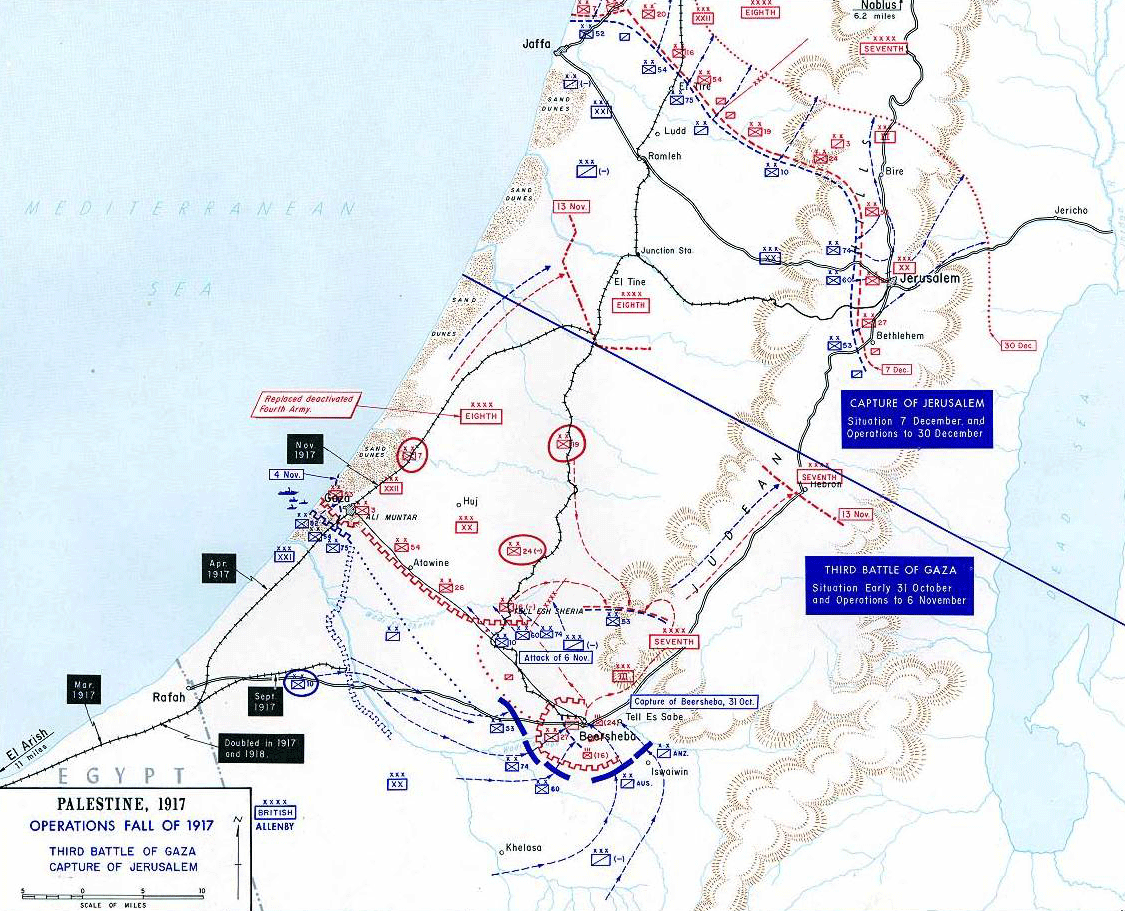

For the third attack on Gaza, General Allenby decided to focus first on Beersheba, where British intelligence had identified that Ottoman defences were not as strong. If he could take and hold Beersheba, he could be assured of a reliable water-supply (essential to maintain the Army) and could outflank Ottoman positions at Gaza. His plan involved moving infantry and cavalry units gradually into positions over ten days, to avoid alerting the defenders. In addition, an elaborate deception attempted to mislead Ottoman forces about General Allenby's intentions.

For the attack on Beersheba on 31st October, the 229th Brigade was in divisional reserve. Infantry attacked from the west of the town, but even though the attack was a surprise, and Ottoman forces were weak, there was stiff resistance.

Riding overnight, the Desert Mounted Corps circled around the town to attack from the north-east. In a direct cavalry assault, the largest cavalry charge of the Great War, the defenders were overcome. The infantry moved in from the west, and the town fell. That night the 16th Devons bivouacked north-east of Beersheba, and the following day held a position to the north of the town while the next phase of General Allenby's plans were put into operation. On 1st and 2nd November, other British forces attacked Ottoman positions facing Gaza, while the Desert Mounted Corps moved in the direction of Hebron, north of Beersheba. The purpose was to draw off Ottoman defences from the centre of the Gaza-Beersheba line at Hareira and Sheria, which was General Allenby's next objective.

The attack was launched on 6th November, the 74th Division advancing against the eastern end of the Turkish positions. The 12th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry were in the Brigade front, and the 16th Devons in the rear - for the Somersets' experience, see the story of Bertram Mashford, already referred to - he was wounded in the attack and died the following day. Atkinson includes the following account from one of the Devons' officers, emphasizing the speed of the attack:

The advance was marvellously rapid … we all went on in successive lines … like a pack of hounds. The artillery fire was pretty severe, and so was the machine-gun fire, and all the time there was enfilade fire from our right.

Supports and reserves had to reinforce the leading battalions, and all units became heavily intermingled, some of the Devons becoming involved in the attack of the 230th Brigade to the right, helping to defeat an attempt by Ottoman forces to recapture a battery. Nonetheless first objectives were secured and the 229th Brigade then reorganized for a fresh advance to the left, against positions near the Sheria-Beersheba railway line. Although this attack was successful too, there were some casualties - the 16th Devons lost their commanding officer and four men killed, while three other officers and 35 men were wounded.

General Allenby's plans were successful - that night, Ottoman forces withdrew, evacuating Gaza (which had been heavily bombarded). For the next fortnight, the 74th Division, including the 16th Devons, remained encamped near Gaza, while the British advanced towards Jerusalem. On 14th November, the British captured an important railway junction ("Junction Station" on the map below) to the south-west of Jerusalem, cutting the Jaffa to Jerusalem railway and securing a key centre of communication. The following day Ramla and Lidda were taken, and Jaffa was occupied on 16th November.

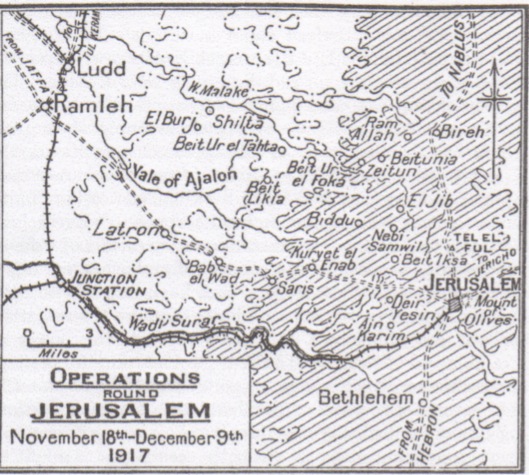

Ottoman forces (the Seventh Army) then fell back into the Judean Hills to defend Jerusalem. Here the British advance slowed down, meeting stiff resistance and operating in very demanding conditions. General Allenby thus brought up fresh forces from Gaza, including the 74th Division. On 22nd November, the 16th Devons left Gaza, and on 28th November they reached the village of Latrun, west of Jerusalem, coming into the line on 1st December. In the meantime Ottoman forces had launched a series of counter-attacks against positions held by the British. In particular, the village of Beit Ur El-Foqa was lost on 30th November.

At 1am on 3rd December, the 16th Devons launched the attack to recapture the village "in a desperate scramble over steep and broken ground". The village was taken at about 3am, 60 prisoners and 3 machine guns being taken also. But Ottoman counter-attack was immediate, with fierce fighting involving bombs and bayonets at close quarters. As daylight broke, it became clear that the position was impossible to hold, because it was overlooked by higher ground from all sides, including from the rear. Nor could any defences be quickly constructed, due to the rocky ground. The 16th Devons evacuated the village in the afternoon, having suffered heavy losses (see below).

Those that remained were withdrawn to reserve and took no part in the very severe fighting against Ottoman forces in the Judean Hills. But by 8th December, all the city's prepared defences had been taken, and neither the British nor the Ottomans, and their German allies, wanted to fight in Jerusalem itself, running the risk of damaging shrines sacred to three of the world's great religions. Ottoman forces were withdrawn from Jerusalem after sundown on 8th December and the city was surrendered the following day. General Allenby made a carefully choreographed entry to the city, on foot, through the Jaffa gate, on 11th December 1917.

In Dartmouth, the bells of St Saviour rang out to celebrate the entry of British troops into the city. Leaving aside any religious dimension in what was predominantly a Christian country, this was a significant victory after many months of bitter disappointment.

Death

The 16th Devons sustained heavy casualties in this operation; five officers and 140 men were killed or missing, and nine officers and 132 were wounded.

Henry was reported as missing in a casualty list of 10th January 1918 and it would seem that his body was not found, or could not be identified - the Devonshire Regiment British War and Victory Medal Roll states "death regarded 3.12.17".

Commemoration

Henry is commemorated on the Jerusalem Memorial, within in the Jerusalem War Cemetery. The memorial commemorates 3,300 Commonwealth servicemen who died during First World War operations in Egypt or Palestine, and who have no known grave.

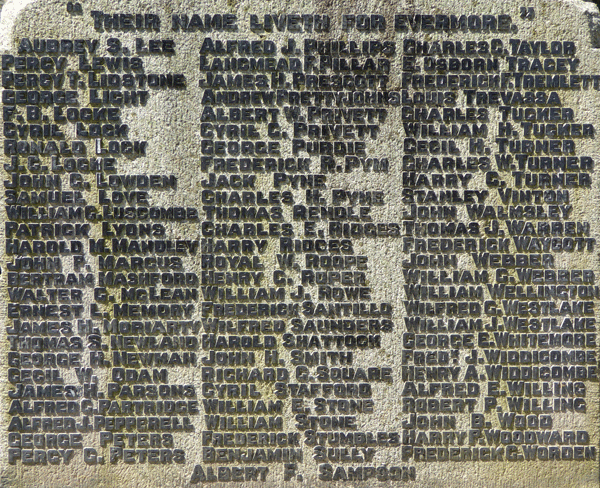

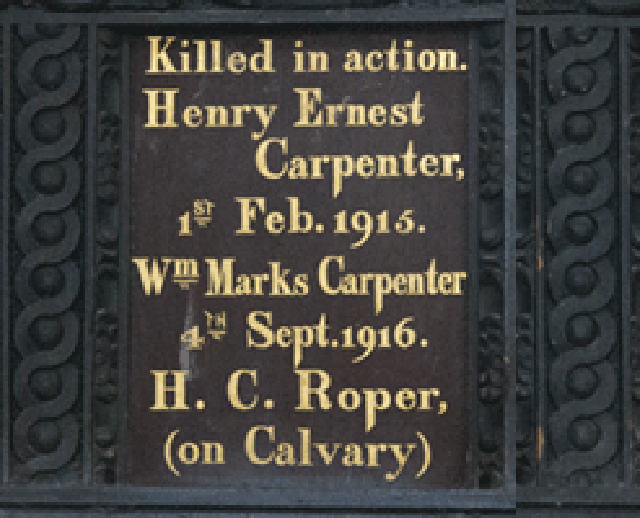

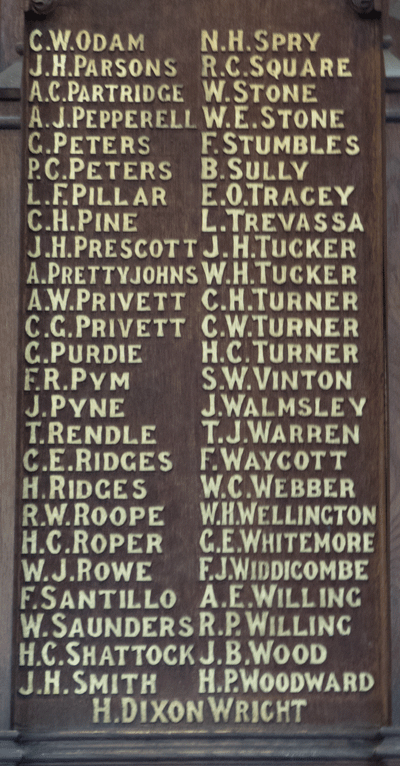

In Dartmouth, Henry is commemorated on the Town War Memorial, the St Saviours Memorial Board, and on the Memorial in St Petrox. Some indication of the religious resonance to the deaths involved in the Palestine campaign is given by the description on the St Petrox Memorial of where he died - "On Calvary".

Sources

The Devonshire Regiment 1914-1918, complied by C T Atkinson, publ 1926, London and Exeter

The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East 1914-1920, by Eugene Rogan, publ 2015 Allen Lane

The Great War, by Peter Hart, publ 2014, Profile Books

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Roper |

| Forenames: | Henry Chard |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 26783 |

| Military Unit: | 16th Bn Devonshire Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 03 Dec 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 38 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Advance to Jerusalem |

| Place of Death: | Beit Ur El-Foqa, Israel |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Jerusalem Memorial, Israel |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | Yes |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |