William John Evans

Family

William John Evans was born in Dartmouth on 15th February 1893 and baptised at St Saviours on 27th April of that year. He was the eldest of three children of Stephen Martin Evans and his wife Sarah Maria Hayman.

Stephen Evans was born in Kingswear, where his father, also Stephen Martin Evans, was an agricultural labourer. By 1891, Stephen (junior) had moved to Dartmouth to work as a groom, lodging with his eldest brother John and his family, on the Embankment.

In 1892, Stephen married Sarah Maria Hayman, one of two surviving daughters of Thomas Hayman, a sailor, and his wife, Rhebena Roberts. Thomas had worked on ships sailing from Dartmouth to Liverpool and had met Rhebena in the city; Sarah and her elder sister Edith were born there. Sadly, Thomas Hayman had died when Edith was five and Sarah was three, and their younger sister, Mary Ellen, born that year, died two years later, in 1877. Their mother Rhebena then formed a relationship with Robert Davies, a dock labourer, by whom she had four children. She remained in Liverpool - Edith and Sarah were not recorded living with her in the 1881 Census. It appears that they moved to Dartmouth to live with their paternal grandparents, Thomas Masters Hayman and his wife Maria Allery. Thomas Masters Hayman farmed at Lower Swannaton, just outside the town.

By the time of the 1891 Census, Edith had married. She and her husband, George Henry Marshall, and their infant son Thomas, were recorded sharing a house in Lake Street, Dartmouth, with Thomas and Maria Hayman, and Sarah Maria, aged 19. Sarah worked as a dressmaker; her grandfather, though aged 72, was recorded as a "general labourer".

Stephen and Sarah made their home in Lake Street too, where William was born in 1893. By the time their next child, Ethel Mary, was born, in 1896, Stephen and Sarah had moved to Silver Street (now Undercliff). The 1901 Census recorded them living there with the two children and also Sarah's uncle, her mother's brother John Allery. Stephen worked as a domestic gardener and coachman.

By 1911, William, now 17, was working for, and living with, Frederick Sanders Bowhay, a butcher in Victoria Road (for more on the Bowhay family, see the story of Harry Bowhay). William worked as Frederick's Assistant; Frederick's brother in law, Arnold Lentern, aged 14, was an apprentice.

William's parents, Stephen and Sarah, still lived in Silver Street, with Ethel, aged 15, and their younger son Frederick, born in 1907. Stephen now worked as a cartman for a coal merchant; Sarah continued to work as a dressmaker, on her own account.

Service

Like so many, William's Army service papers have not survived. However, his name appeared in the first list published in the Dartmouth Chronicle of "Dartmouth patriots who have responded to the National Call to Arms during the present great European War", on 11th September 1914. As this indicates, he was amongst the first in the town to join up. Along with several other men from Dartmouth, he joined the 8th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment. The eager recruits, including William, featured again in the newspaper on 25th May 1915, looking forward to their arrival in France. They disembarked on 25th July 1915 - see the story of Andrew Prettyjohn, who was the first of the men of Dartmouth in the 8th Battalion to be killed in action, on 8th September 1915.

On 25th September 1915, the 8th Devons went into the attack at the Battle of Loos, where eight more men from Dartmouth lost their lives. For the Battalion's experiences at Loos, see our separate article.

The 8th Devons then served in the Cuinchy sector until they moved south to the Somme, at the end of 1915. For their experiences after Loos and during the early part of 1916, see the stories of George Burnell, killed whilst on sentry duty at Becordel on 10th February 1916, and Thomas Arthur Chase, who was serving with the 8th Devons until he was wounded sometime in early March 1916.

The 8th Devons spent the months leading up to the opening of the Battle of the Somme in the southern part of the sector, near Fricourt. On 1st July 1916, the 8th Devons were in Brigade Reserve for the attack, required to move up into the trenches vacated by 9th Devons, as soon as they had gone forward in the attack on Mametz. For the action on 1st July 1916, involving the 8th and 9th Devons, see the story of Robert Phillips Willing. The attack was successful, but the 8th Bn lost three officers killed, with 47 men killed or missing, and seven officers and 151 men wounded.

William's name appears as one of those "wounded" in the Devonshire Regiment in a casualty list of 31st July 1916 (though the list does not of course refer to any particular action). The names of the vast majority of those killed in the 8th Battalion on 1st July (as we now know) appeared in a casualty list published very soon after, on 5th August 1916. This suggests that William was most likely wounded in the attack on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

No record or other information has yet come to light about the severity of William's injury, how long he took to recover, or where he was during that time - whether treated in France, or back home in "Blighty". At some point, however, most likely after he had recovered, he was transferred to the 6th Battalion of the Dorset Regiment, and given a new service number, 22168.

The 6th Dorsets were also on the Somme. On 1st July 1916 they had been in reserve, but were ordered up later in the day to take forward the attack on the Fricourt salient. Fortunately for them, the attack was cancelled only ten minutes before they were due to go in. In August they were first at Longueval, near Delville Wood, and then at Hebuterne, a relatively quiet sector, where they remained for much of September. They came back into the front line at Le Transloy at the end of October. For the conditions at that time, see the story of Thomas Arthur Chase, referred to above, who by that point had also transferred from the Devonshire Regiment to the Dorset Regiment, number 22837. His number is higher than William's, which may suggest that William transferred to the Dorsets before Thomas. If so, the date of Thomas' death - 9th November 1916 - provides a latest date by which these transfers must have taken place.

By 15th November 1916 the 6th Dorsets were "at rest" at Molliens Vidames, west of Amiens; but they returned to the Somme front a month later, to spend Christmas week in the trenches at Les Boeufs. The conditions were extremely challenging. According to the War Diary:

A great deal of work was done in this tour. The battalion got an extra day in the trenches, but when it was relieved by the 22nd Australian Battalion on Jan 2nd there was dry standing for all the garrison of the front trenches. This meant a reduction of about 3 feet of water by incessant pumping and bailing.

They remained in the same sector until 20th February, when they moved to Meaulte for rest and training, plus much-needed baths, and issue of new clothes. The War Diary comments that "shirts drawn [ie to replace those taken off] were poor, several of them being "alive" with lice". From Meaulte, they moved to Warloy, north west of Albert, for "intensive training" according to a programme prepared by the Brigade called "Attack on Strong Point", where they stayed until 14th March 1917.

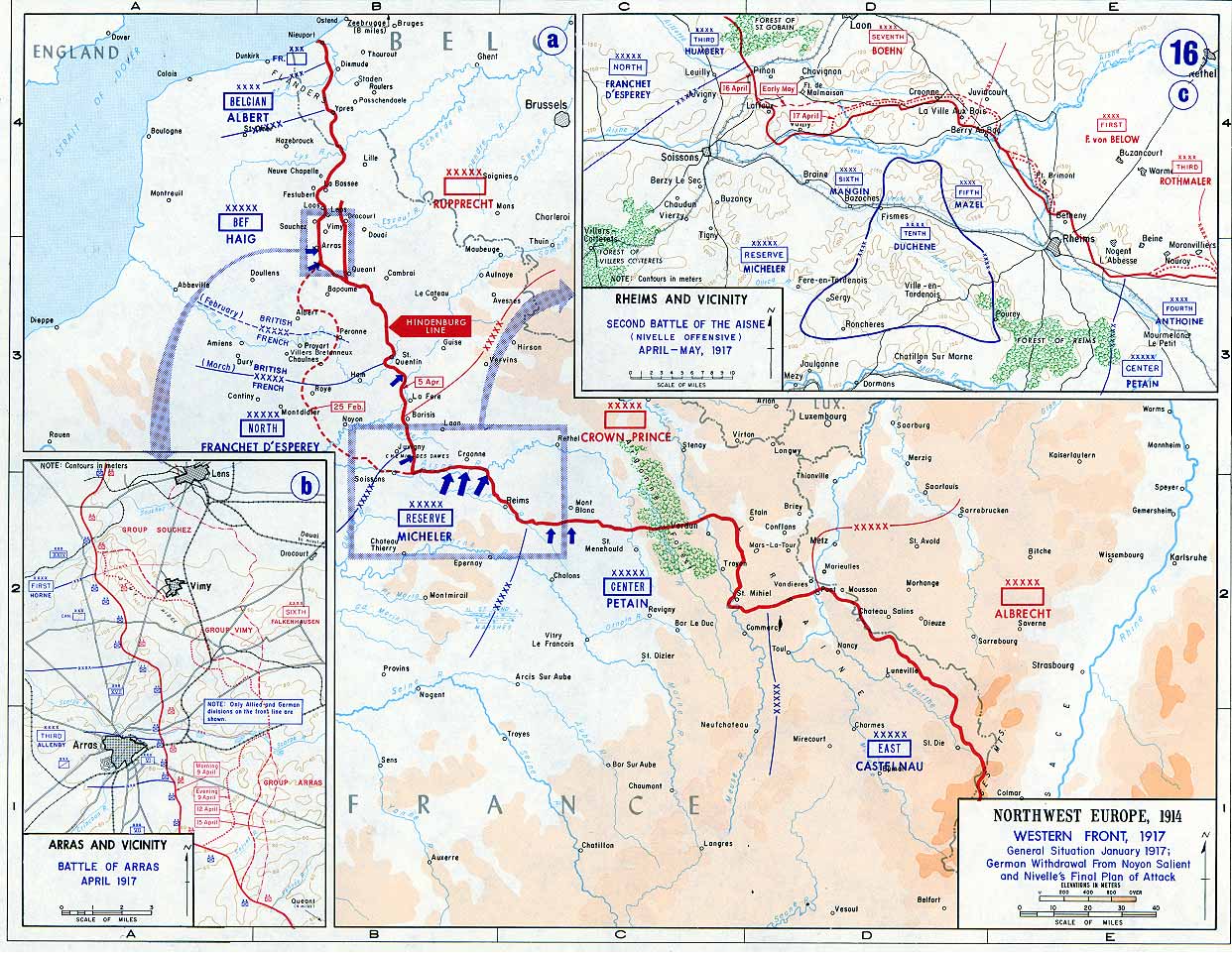

The Battle of Arras

While the Dorsets were honing their attacking skills, the strategic situation changed. During the middle of March, the Germans withdrew to the new line of defence called, by the British, the Hindenburg Line. The British front had moved forward, away from the old battleground of the Somme. For the coming spring, a major offensive was planned by the British around Arras, diversionary to an even larger French attack further south. For the background to the plans for the Arras offensive, see the story of Cyril Stafford.

Between 14th -16th March, the Dorsets were moved north to Fillievres, and after a week there, to Ivergny, closer to Arras, where they remained, still training, until 3rd April. Unfortunately, the Battalion War Diary is missing the usual daily summary sheets between 31st March and 18th April, but other enclosures enable the reconstruction of the Dorsets' activities and movements.

17th Division (of which the Dorsets were a part) was in reserve for the first day of the Arras offensive, which began on 9th April. Two days before, they had moved to the village of Montenescourt, a few miles to the west of Arras, where they celebrated Easter. On 10th April, they were brought forward, moving into billets in Arras itself, and on the 11th April, came into the new front line, replacing 15th Division between the village of Monchy le Preux and the River Scarpe, to the east of Arras. Monchy had been taken after very fierce fighting, the previous day.

On 12th April, they were ordered to continue to take the attack forward against the new German defensive lines east of Monchy. Verbal orders were issued at 3.30pm; zero hour was 6.20pm. They had had very little time to familiarise themselves with the ground, and they faced heavily fortified enemy positions. Furthermore, there had been no time to bring forward enough heavy artillery to deal with the strength of the enemy defences.

"A" Company was on the right of the Battalion's front, "C" in the centre and "D" on the left; "B" company was in Battalion reserve. The report of the action included in the Battalion's War Diary states that:

From the start "C" and "D" Companies were subjected to heavy hostile machine gun fire ... The three companies all reached the first objective, but "C" and "D" Companies suffered heavy casualties, all the officers of both companies being either killed, wounded or missing, with the exception of one. These heavy casualties are attributed to the lack of artillery preparation. The area from which the hostile machine guns fired had been almost entirely missed by the artillery fire. To the south of the River Scarpe the artillery fire was observed to be extremely erratic. No regular barrage was apparent, the ground for a depth of 2000 yards being bespattered with shells.

The attack was delayed at this point, other divisions having also been unable to make progress. Two platoons were sent forward from "B" Company to reinforce "D" Company and one to reinforce "C" Company; the position reached was consolidated and patrols sent out, which met the enemy's advanced posts about 200 yards east of the position gained. At about 11pm, orders were received to return to the original British front line as soon as the 7th East Yorkshires had been brought up to hold it. The operation was completed, leaving the 7th East Yorkshires holding the original front line, "as daylight was breaking". Nothing had been gained and the Battalion had suffered heavy losses - three officers had been killed with one missing believed killed, and four were wounded; amongst the men, there were 20 killed, 61 wounded with three missing.

The Battle of Arras continues: the "Second Battle of the Scarpe"

During the next few days, while there was a brief pause in British operations, it became clear that the attack launched by the French further south on 16th April would not provide the immediate and much longed-for breakthrough that had been promised. To maximise the chances of success overall, and despite misgivings at the highest level, pressure had to be maintained through continuing with the British offensive around Arras.

A renewed attack took place on 23rd April 1917, on a nine-mile front between Bailleul, to the north-east of Arras, and Bullecourt, to the south-east. For the fighting north of the River Scarpe, see the story of James Henry Moriarty. The 6th Dorsets were involved in the attack immediately to the south of the river.

The 6th Battalion's War Diary resumes its daily account a little beforehand, on 18th April, when the Dorsets moved up past the "Railway Triangle" (the intersection of the Arras-Lens and Arras-Douai railways) and the following day relieved the 10th Sherwood Foresters in the Support Line at Orange Hill, to the west of Monchy le Preux. Battalion HQ was shelled and one fell in the midst of carrying parties, killing one man and wounding fifteen others.

On 21st April, they were relieved and returned to the shelter of the underground caves in Arras, coming back the following night into the same trenches for the attack. As they left the Caves for the trenches, at 11.30pm, a shell fell at the head of the exit, killing six men and wounding six more.

At 3am on 23rd April, they arrived at their designated positions in support behind the 7th Lincolns, who were behind the 7th Borders - who were to lead the attack in that sector of the line. Behind the Dorsets were the 7th Yorks. The attack went in at 4.55am after about ten minutes of "intense bombardment"; at about 8am the Dorsets moved up into the original British front line.

According to Jonathan Nicholls, the movement of the 7th Borders to the jumping-off trench had been seen by a concealed enemy outpost, and they were easily targeted. He quotes Private Reg Eveling of the 7th Borders:

As soon as we went over I kept well back from the creeping barrage ... Then we came to the barbed wire and it wasn't properly cut ... It was sheer murder ... There were paths cut through the wire and, like animals, we crowded into the paths. That's where most of our casualties came from, machine guns were trained on the gaps, blokes just fell in heaps ... I looked to my left and right and couldn't see another soul ... I dived into the nearest shell hole and stopped there till it was dark.

The 7th Borders lost 15 officers and 404 other ranks, although one of the attacking companies did manage to take a German strong point, which they were able to enlarge and consolidate.

When the 7th Lincolns moved up, they too were seen by the concealed enemy outpost. Furthermore, a request that the creeping barrage be brought back to cover their advance was refused. When 17th Division then cancelled their attack, the message did not reach them in time - so they went forward without any artillery cover. As they reached the wire, they too were cut down.

At 6.30pm the Dorsets in their turn went forward to continue the attempt to take the objective of "Bayonet Trench", but, according to the Dorsets' War Diary:

... our men were unable to occupy it, although they were almost on it, on account of the severe machine gun fire from front and north bank of Scarpe River, which inflicted heavy losses on the companies as they advanced the 1200 yards from the Trench from which they set off. "A" and "B" Coys especially suffered heavy losses."

Again it seems that the artillery preparation had been insufficient; the wire had not been cut, and, as on 12th April, enemy machine gun positions north of the river were untouched, with the same terrible results. At 3am on 24th April, they were relieved by the 7th Yorks, in reserve behind them, and returned to the original British front line; from there, on 25th April, they were relieved at 11.30pm, and returned to their billets in Arras, arriving there at 2am on 26th. Later that day, they were taken to their rest billets west of Arras by train.

According to the Battalion War Diary, two officers were killed and four wounded; amongst the Warrant Officers, NCOs and men, seventeen were killed, with 84 wounded and three missing. Total battle casualties for April, adding together those for 12th and 23rd, were 235.

Along the whole front, some gains were made - the villages of Gavrelle and Guemappe. But, in an all too familiar story, a terrible price had been paid.

Death

It is evident that there was considerable uncertainty about what had happened to William after the Dorsets' participation in the two actions described above.

On 15th June 1917, William's name was amongst those reported as "wounded" in casualty lists appearing in West Country newspapers. A further report appeared in the Western Times of 3rd July 1917, when his name appeared as one of those "previously reported wounded, now reported wounded and missing".

At the same time, Stephen and Sarah, William's parents, evidently received official news too. The Dartmouth Chronicle of 20th July 1917 reported, in its "Local Intelligence" column (all too frequently used for news of this kind):

Wounded and Missing: Mr and Mrs Evans, of 4 St Saviour's Place, have received information from the War Office that their son Private W J Evans, of the Dorsets, was wounded on April 25th, and has since been missing. Private Evans was one of those who volunteered on the New Ground at the commencement of war, and was only 23 years of age. He was previously employed by Mr Bowhay, butcher, of Victoria Road.

Set against the account in the 6th Dorsets' War Diary, the quoted date of 25th April for William to have been wounded and gone missing, appears odd. No casualties were reported there as having occurred on 25th April, which was the day on which the Battalion moved back into Arras from the original British front line, though of course many were incurred in the attack two days earlier.

William's death was not officially confirmed until 2nd November 1917, when West Country newspapers reported him "previously reported wounded and missing, now reported killed". The date of 25th April was apparently now regarded as the date on which he had been killed, rather than wounded. All official records therefore give his date of death as 25th April 1917.

Commemoration

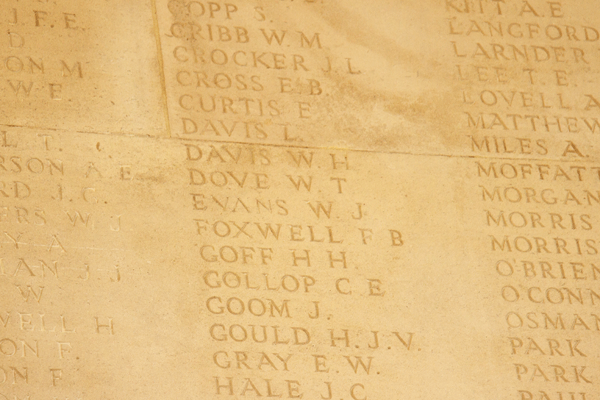

William's body was never found (or was never identified). He is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, which records the names of almost 35,000 men dying in the Arras sector between spring 1916 and early August 1918, who have no known grave.

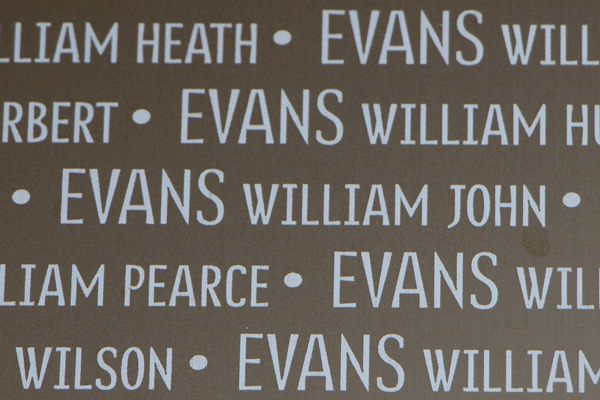

As one of the 579,206 casualties in the region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, William is also commemorated on the new memorial at Notre Dame de Lorette, "The Ring of Memory".

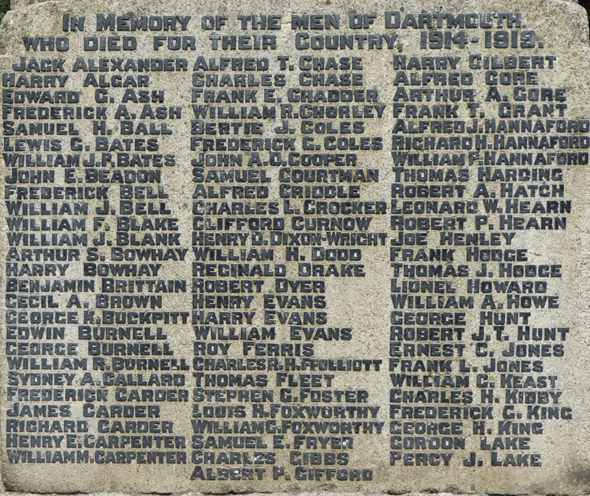

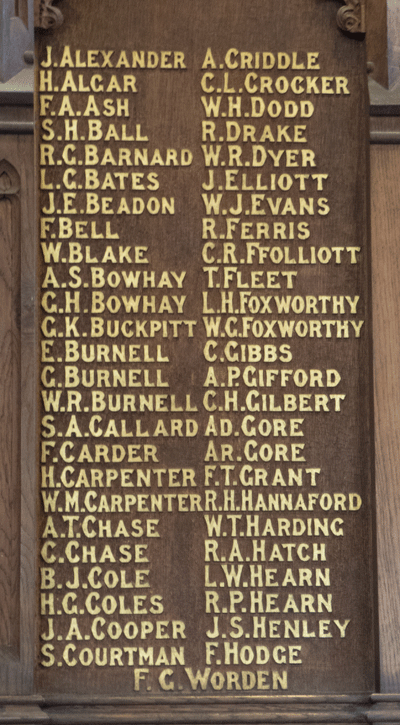

In Dartmouth, William is commemorated on the Town War Memorial and the St Saviours War Memorial Board.

Sources

The War Diary of the 6th Battalion Dorsetshire Regiment is available for download from the National Archives (fee payable), reference WO 95/2000/3 (1st July 1916 - 31st December 1916) and WO 95/2000/4 (1st January 1917 to 30th April 1917).

West Country Regiments on the Somme, by Tim Saunders, publ Pen & Sword, 2004

Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras 1917, by Jonathan Nicholls, publ Pen & Sword 2005, reprinted 2015

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Evans |

| Forenames: | William John |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 22168 |

| Military Unit: | 6th Bn Dorsetshire Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 25 Apr 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 24 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of Arras |

| Place of Death: | Near Monchy le Preux, France |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Arras Memorial, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | "The Ring of Memory" at Notre Dame de Lorette |