James Henry Moriarty

Family

James Henry Moriarty was born in Dartmouth in 1895. He was the younger of two surviving sons of Patrick Moriarty and his wife Mary Ann Gore, both of whom came to the town from elsewhere.

Patrick Moriarty was born in Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland, in 1852. He joined the Navy in 1867 as a Boy 2nd Class, signing on for a ten year continuous service engagement in 1870. He first came to Dartmouth in October 1875, when as an Able Seaman he was appointed to HMS Britannia, at that time still the old wooden training ship moored in the Dart. His tour in Britannia lasted two years, and it seems that during this period he met his future wife, Mary Ann Gore.

Mary Ann was born in Teignmouth in 1857. She was a younger daughter of John Gore, a police constable, and his wife Sarah. Soon after Mary Ann's birth, John was posted to Slapton, and Mary Ann was baptised there in 1860. By the time of the 1871 Census, however, John had left the police force. He and his family moved to Dartmouth, where the Census recorded them living in Higher Street. Mary Ann's eldest brother James had joined the Navy and was already serving in HMS Britannia, where he remained until at least 1889. He most probably knew Patrick Moriarty, which may have been how Patrick and Mary Ann met. For more on James Gore and his family, see the story of Alfred Francis Gore, Mary's nephew.

In September 1877, Patrick's time in HMS Britannia came to an end. His next appointment took him back to southern Ireland, to HMS Black Prince, the harbour training ship in Queenstown (now Cobh). But from July 1878 he was once again in Devon, this time in Plymouth, where he stayed for some time, alternating between HMS Indus and HMS Royal Adelaide. In early 1879, he and Mary Ann married in Plymouth. Their first home was at 5 Prospect Place, where their first child, Patrick John Moriarty, was born in July 1879. Very sadly, the little boy lived only three days. He was buried in Ford Park Cemetery, Plymouth, on 30th July 1879.

Patrick and Mary Ann's second child, Lily, was born on 20th November 1880, also at 5 Prospect Place. By the time she was born, Patrick had been sent to HMS Penelope, the guard ship at Harwich, where he remained until April 1881. Perhaps he was home on leave, for the 1881 Census, taken at about the same time, recorded him not in Harwich but in Prospect Place with Mary Ann and Lily, four months old. His occupation was given as "bluejacket in Navy" - the previous year he had signed on for a further ten years service, to qualify for a pension.

In May 1881, Patrick joined HMS Hercules, the flagship of the Reserve Squadron, under command of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, the second son of Queen Victoria, which took him to the Baltic and to the Mediterranean. He was most probably away at sea when Mary Ann gave birth to their second daughter, Elsie May, in Plymouth in 1882. His next appointment, in December of that year, to HMS Thalia, took him to the Straits Settlements and Hong Kong, taking out new crews for HMS Curacoa and HMS Victor Emmanuel - he appears then to have transferred to Victor Emmanuel, remaining in Hong Kong. He finally returned to Devonport in 1885.

In 1886 he was once again appointed to HMS Britannia, and so the family returned to Dartmouth, where Mary Ann's family still were. Patrick remained in HMS Britannia until he reached the end of his naval service on 14th April 1890. A third daughter, Florence Mabel, was born in Dartmouth in 1887, and another son, Frank, in 1889. At the time of Frank's baptism the family lived in Foss Street, but by the 1891 Census, they had moved to Crowthers Hill. Although Patrick had left the Navy, his occupation was still given as "seaman". Another son, John, was born after the Census, in 1891, followed by Rose in 1893, James Henry in 1895, and Gertrude Kate in 1896. Sadly, John died aged not quite seven years old, in 1898.

With a large family to support, Patrick could not rely only upon the income from his naval pension, and by the time of the 1901 Census, he was working as a general labourer. The family lived in Above Town; Elsie and Florence were by this time both working in domestic service, though Florence was only thirteen. Lily had married a few months earlier - her husband, Patrick Flynn, was an Able Seaman in the Royal Navy, like her father, and also came from Ireland. They had a son John, three months old, and at the time of the Census lived in Duke Street, Dartmouth. (Oddly, in 1901, Lily was also recorded in her maiden name as living with her parents). Lily and Patrick had a daughter, Kathleen, born in Devonport in 1903, but only two years later, Lily died, aged only 26. She was buried in St Clements, Townstal.

By 1911, Patrick and Mary Ann had moved back to Crowther's Hill. Patrick, aged 59, was still working, as a coal porter. Frank had left home and was working in Ipplepen, where he was a tripe dresser; Florence and Rose both worked for a laundry company, as did Elsie, who was still living at home despite having very recently married. James Henry, now 17, was working as a general labourer in an engineering works.

Patrick and Mary Ann's youngest daughter, Kate, was still at school; in addition, there were two grandchildren in the household, Violet and Richard Moriarty, aged 4 and 2.

Service

Like so many, James' individual service records have not survived. However, the British War and Victory Medal Roll for the Somerset Light Infantry, the Regiment he was in at the time of his death, shows that he was previously a member of the 7th Battalion Devonshire Regiment - the Devon Cyclists - with the number 1568. Comparison of this service number with others joining the Devon Cyclists, whose papers have survived, suggests he may have joined up in early November 1914 (1562 and 1563 attested on 7th November 1914, while 1572 attested on 9th November 1914). Soldiers Died in the Great War states that he enlisted in Totnes.

At the time he joined the Devon Cyclists, they were serving on coastal defence duties in the north-east of England - see the story of Frederick Bell. By the middle of 1915, they were back in Devon, and indeed still recruiting- see the story of Frederick Coles. Although members of the Territorial Force had no liability to serve overseas, many volunteered to go; and with the coming of conscription in 1916, that limitation was in any case removed. The 7th Devons, as such, never left England, but many of its members transferred to front-line units. A large contingent transferred to the 2nd/8th Worcesters, including Frederick Coles; see also Joseph Henley and Patrick Lyons.

There are no records showing exactly when James transferred to the 8th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry, although his Medal Index Card shows that he did not go to France until some time in 1916. However, the Battalion's War Diary records on 6th August 1916 that:

Draft of 100 OR arrived from Base - 7th Devon Territorial Cyclist Battalion

and on 6th September 1916 that:

100 Other Ranks Devon Regt, and 23 OR Hampshire Regt (attached to this Unit) were transferred as from 30th August 1916, new numbers having been allotted.

It seems highly likely that James was one of this group. The 8th Battalion SLI, a New Army battalion, had disembarked at Le Havre on 9th September 1915 as part of 63rd Brigade, in 21st Division, and very soon after had fought at Loos, suffering heavy casualties. At the beginning of 1916, they were in the line near Armentieres, but were moved down to the Somme on 9th April 1916 and went into the trenches in the southern part of the front, near Fricourt. They attacked there on 1st July 1916; during the first three days of the battle they sustained approximately 50% losses.

On 6th July 1916, their Brigade transferred from 21st to 37th Division, and shortly afterwards, they were transferred to the sector between Arras and Lens, near Souchez, opposite Vimy. During August and early September they were out of the line; when they finally took over trenches near Souchez in late September the situation was, in general, "quiet". Here, it appears, James and the other Devon Cyclists joined them.

Towards the end of October, having received further reinforcements, the 8th Somersets were once again sent back to the Somme. On 18th November, they were brought into the very last phase of the Battle of the Ancre, itself the last phase of the Battle of the Somme, in an attack on Pusieux Trench. Weather and ground conditions were horrendous; they suffered heavy enemy rifle fire; and the attacking companies were also hit by the British barrage - the attack was halted while the barrage was stopped. Bombing parties then entered the trench and took it; it was held, but no further advance was made. Casualties were high - four officers were killed, including three Company Commanders, and "up to" 100 other ranks. They were relieved that evening, remaining in support; on 20th November they moved into "old German second line" and spent the next three days on battlefield clearance, leaving the Somme finally on 24th November. They then marched by stages to billets in L'Ecleme, north west of Bethune; and on from there to Paradis, north of Bethune. Here they spent December and presumably, celebrated Christmas (though the Battalion War Diary is silent on the point).

On 8th January 1917 they were back in the front line near Neuve Chapelle for a week, obtaining "valuable information" (unspecified in the War Diary) when carrying out patrols of the enemy's wire. On 28th January, they were back in the line again, but this time only for two days, moving into Bethune on 1st February; after a fortnight in Bethune, they took over trenches near Loos until 3rd March 1917. Since the start of the year, casualties had been very low, but the winter of 1916/1917 was extremely harsh. The War Diary reports quite a lot of sickness amongst the officers, necessitating many comings and goings, so this was probably an issue amongst the men too.

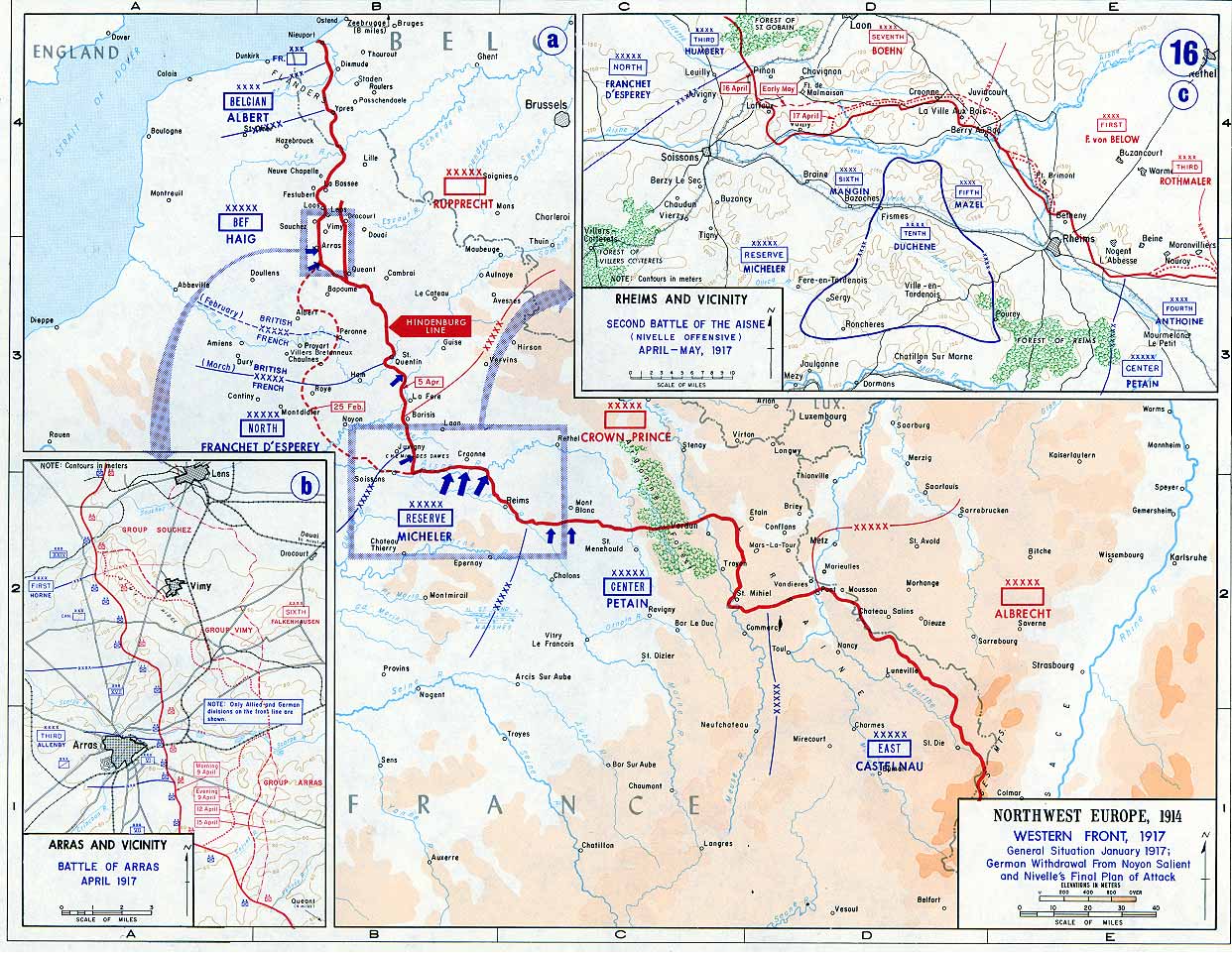

The Battle of Arras

In the first week of March, the Battalion moved out of the front line, southwards to the little village of Monts en Ternois, where they spent the remainder of the month in training. During the middle of March, the Germans accomplished their withdrawal to the new line of defence called, by the British, the Hindenburg Line, and a major offensive was planned by the British around Arras, diversionary to a very large-scale French attack further south. For the background to the plans for the Arras offensive, see the story of Cyril Stafford.

The 8th Somersets' War Diary makes little reference to the wider context for their activities, noting only that "a number of officers have been attached for two days at a time to a Division in the line at Arras", presumably to be briefed on the planned attack and to familiarise themselves with the ground, so far as possible. The plan for the infantry attack involved not just an initial assault but also required supporting infantry divisions to "leapfrog" through the positions gained, so as to maintain forward momentum and penetrate deep into enemy lines. 37th Division was positioned in the centre of the Third Army's front, behind the attack of the 15th (Scottish) and 12th (Eastern) Divisions, ready to "leapfrog" through at the right moment, and (it was hoped) capture the village of Monchy le Preux.

The 63rd Brigade, of which the 8th Battalion was a part, was in Divisional Reserve. They began their march to the battlefield on 5th April, arriving at Duisans, on the western outskirts of Arras, at 11.30am on 8th April; at 5.30am on the morning of the 9th April, as the attack began, they took the road to Arras to their assembly positions. The 12th and 15th Divisions, leading the attack in the centre, had made excellent progress, and in the middle of the afternoon, 63rd Brigade advanced to a position called Battery Valley, a deep depression between Arras and the village of Monchy le Preux, where enemy artillery had been positioned to shell Arras.

At about 7.30pm the Brigade advanced to Orange Hill, the Somersets leading on the right of the Brigade front, and dug in. The attack toward Monchy was resumed at 7.30am on 10th April, with the Somersets again on the right of the Brigade front, aiming for a position called Lone Copse Valley. The advance took place under heavy shell and machine-gun fire, but by the evening a line was consolidated along the crest of the ridge west of Monchy.

On 11th April, the attack on Monchy continued, with the 37th Division in the centre of an attacking front of three divisions. Once again the 63rd Brigade was in Divisional Reserve, waiting for the advance of those in front; and the Somersets were in Brigade Reserve. Monchy was taken that day after very heavy fighting, much of it street-to-street and house-to-house; but the Somersets were not required to move forward, and remained in the same position all day. At 4am on 12th April they were brought out of the action, staying that night in Arras and returning to their billets in Duisans on 13th April.

Although they had been in reserve, they had still incurred significant casualties, 103 in all - two officers and 70 men were wounded; 26 men were killed and 5 were missing.

While the Somersets rested and reorganised, General Robert Nivelle, Commander in Chief of the French Armies on the Western Front, launched his massive attack on a forty kilometre front on 16th April. Crucial documents giving details of his plans had been captured by the enemy in February, and they had plenty of warning and time to prepare, concentrating their forces accordingly. The preliminary bombardment was massive, but even so, not intense enough. On the first day, there was some early success but casualties were extremely high. and it was already clear that "breakthrough" was unlikely for some time. Pressure thus had to be maintained at Arras, and a further British offensive was planned.

The Battle of Arras continues: the "Second Battle of the Scarpe"

The renewed offensive west of Arras took place on a nine-mile front between Bailleul, to the north-east, and Bullecourt, to the south-east. There had been very little time for preparation and reconnaissance, and much heavy artillery was still too far back to assist with the barrage. Further, several of the nine divisions involved had been part of the fighting earlier in the month, and were reduced in number and in experienced officers.

37th Division, including the 8th Somersets, had been moved up to relieve 4th Division on the night of 20th/21st April, and were to the north of the whole front. Their final objective was the northern end of "Greenland Hill", behind, or to the east, of the village of Roeux, and straddling the Arras-Douai railway. Today the area of ground which was their objective is occupied by the intersection of the A1 and A26 autoroutes.

Roeux was an extremely heavily fortified position, with a large blockhouse concealed in the outbuildings of an old chateau, connected by tunnels to a derelict dye factory near the railway station, known as the Chemical Works. In and around Roeux were no fewer than three enemy divisions. 37th Division attacked to the north of the village; 51st (Highland) Division attacked the village itself.

As the attack was launched at 4.45am on 23rd April, 63rd Brigade was on the right of the divisional front; the 8th Somersets were in support behind the 4th Middlesex on the right of the Brigade front; while on the left the 8th Lincolns were supporting the 10th Yorks and Lancs. The area was thick with a dense mist, intensified by smoke from the British barrage. By 6.30am, the Middlesex had succeeded in reaching a line 200 yards east of the road running between Roeux and Gavrelle, the neighbouring village to the north, but then came under heavy enfilade fire from both flanks and could go no further. To their left, the Yorks & Lancs had been unable to reach and take Chile Trench, from where heavy enemy fire prevented the Middlesex from moving forward. The Lincolns, however, were able to pass through the Yorks and Lancs, and their attack on Chile Trench eventually forced the enemy troops there to surrender.

Behind the Middlesex, the Somersets ground to a halt within 200 yards of the start-line with very heavy casualties - only two officers remained (Captain Saunders and 2nd Lt Owen) of fourteen that started. According to the account of the operation in the Battalion's War Diary:

The 8th Somerset LI with the 4th Middlesex in front pressed straight on to the cross roads ... Progress during the morning was slow, owing to direct rifle and machine gun fire. By noon the 8th Lincolns [on the Battalion's left] had reached Cuba Trench ... but a party of our troops were still held up by a party of 50 or 60 Germans [in Chile Trench] ... These surrendered to the OC 8th Lincolns who ... approached them from the rear. The 8th Somerset LI meanwhile had collected their main body in the sunken road south of the cross roads .. At this stage the Adjutant was wounded and [the Commanding Officer] was killed, while the enemy in artillery formation came down over Greenland Hill to a trench about 800 yards [away from] the sunken road running parallel to it ...

Captain Saunders collected all Somersets and dug in [in] Clasp Trench ... The afternoon was spent ... in the consolidation of Clasp Trench. The relief was accomplished the same night [24th/25th April] without incident, the Battalion returning to Heron Trench about 200 strong in other ranks ...

A map of the area where the attack took place may be seen here, showing the position of Clasp Trench just to the west of the motorway intersection.

The 8th Somersets' War Diary shows officer casualties for 23rd April as two killed and ten wounded, two of whom later died of their wounds. Unfortunately, casualty figures for the men are given as a total for the period from 20th - 28th April, during which the Battalion was in action twice, and are not broken down by date. Total figures for that period for other ranks are:

| Killed: | 17 |

| Wounded: | 180 |

| Missing: | 99 |

However, the impact on the Battalion is clear from the statement that those returning after the attack on 23rd April numbered only about 200.

Although 51st (Highland) Division initially took the village of Roeux, they were unable to hold it - they sustained massive casualties in the attempt. To 37th Division's left, however, 63rd (Royal Naval) Division had succeeded in taking the village of Gavrelle.

Death

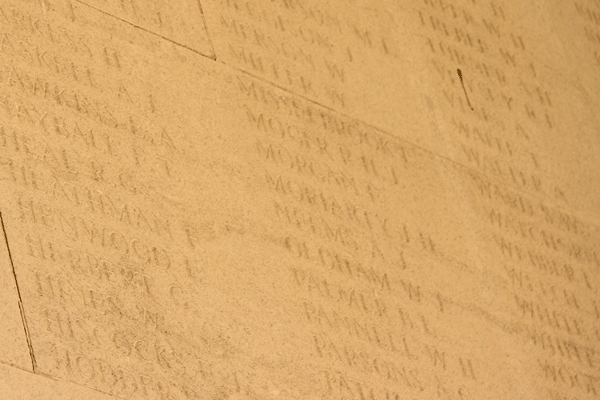

It seems that James was one of those missing following the action on 23rd April and that his body was never found, or never identified. Both the Army Register of Soldier's Effects and the Medal Roll for the Somerset Light Infantry state that his death was "presumed" to have occurred on 23rd April 1917. Accordingly this is the date now recorded for his death by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. He is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, which records the names of almost 35,000 men who died in the Arras sector between spring 1916 and August 1918.

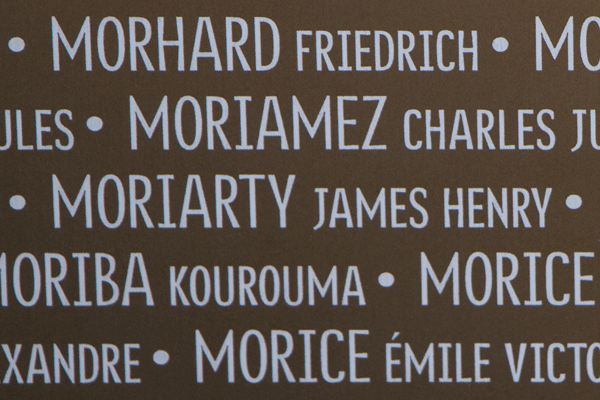

As one of the 579,206 casualties in the region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, James is also commemorated on the new memorial at Notre Dame de Lorette, "The Ring of Memory".

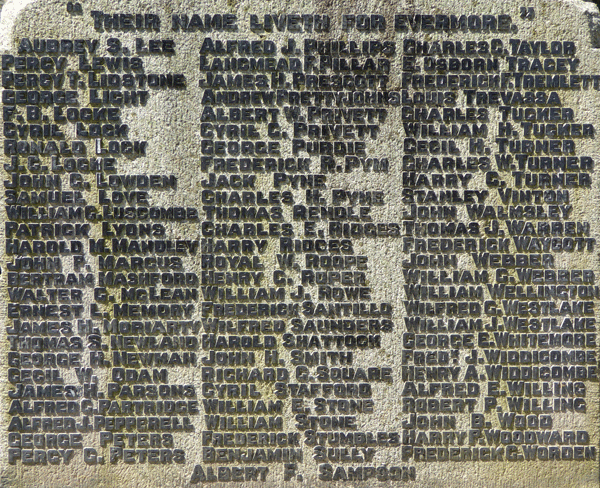

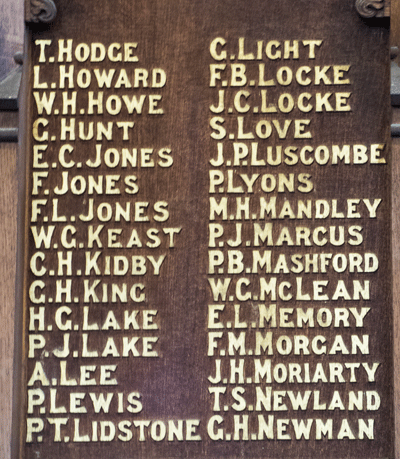

In Dartmouth, James is commemorated on the Town War Memorial and the St Saviour's War Memorial Board.

Dartmouth Museum has on display his official Memorial Plaque.

Sources

Naval Service Record for Patrick Moriarty is available from the National Archives, fee payable for download, references ADM 188/6/40863 and ADM 139/813/1243

The War Diary of the 8th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry, 1916 August to 1919 April, is available from the National Archives, fee payable for download, reference WO 95/2529/2

Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras 1917, by Jonathan Nicholls, publ Pen & Sword 2005, reprint 2015

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Moriarty |

| Forenames: | James Henry |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 29965 |

| Military Unit: | 8th Bn Somerset Light Infantry |

| Date of Death: | 23 Apr 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 22 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of Arras |

| Place of Death: | Not known - see story |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Arras Memorial, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Private Memorial: | His official Memorial Plaque is in Dartmouth Town Museum. |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | "The Ring of Memory" at Notre Dame de Lorette |