Samuel Henry Ball

Family

Samuel Henry Ball was born in Dartmouth on 28th October 1892, the second of six children of George Ball and his wife, Mary Louisa Veale Alford.

George Ball was a carpenter and joiner, born and brought up in Dartmouth. In both the 1871 and 1881 Censuses, his family was recorded living in Crowthers Hill. Mary Louisa Alford was born in Kingswear - her father, Samuel Alford, was a ships carpenter, though in later life he took over the Ship and Plough Inn, in Dodbrooke, Kingsbridge. At the time of the 1881 Census, the Alford family lived in Smith Street, Dartmouth; and presumably George and Mary Louisa met in the town. However, they married in Plymouth, at St John the Evangelist, Exeter Street, on 2nd August 1890. Both were at least temporarily resident in Plymouth at the time - she lived in Exeter Street, a few doors from the church, and George lived in Holborn Street nearby.

By the time of the 1891 Census, George and Mary Louisa had returned to Dartmouth, where they were recorded living in South Ford Road. Mary Louisa was pregnant with their first child, Horace George, born on 5th July 1891 and baptised at St Saviours on 24th September. Samuel, named for Mary Louisa's father, was born thirteen months later, and baptised at St Saviours on 24th November 1892. By that time the family had moved to Crowthers Hill. George continued to work as a carpenter.

Reginald Clifford was born on 18th December 1893 and Gladys Louisa, the only girl in the family, in 1895 - they were both baptised together at St Saviours on 24th November 1895. The family now lived very close to St Saviours, in St Saviours Square. Another little boy, Edward Ernest, was born on 17th December 1896 and baptised in the church on 6th October 1898 - sadly he died only a few months later.

At the time of the 1901 Census, the family lived in Above Town. George still worked as a carpenter and joiner. The four children were all still attending school. Mary Louisa was pregnant with her sixth and final child, John Lawrence. He was born on 21st May, and named in part for George's father, Lawrence Wills Ball, who had died the previous year. Mary Louisa's parents had retired from the pub trade and had returned to Dartmouth; George's mother, Elizabeth, still lived in the town too.

Although there does not appear to have been any prior connection in the family with the Royal Navy, Samuel's brothers Horace and Reginald both made the service their career. Horace arrived at HMS Impregnable in Devonport as a Boy 2nd Class in February 1907, and Reginald followed him two years later in February 1909. So the 1911 Census recorded only Samuel, Gladys and John at home with George and Mary Louisa. Samuel, aged 18, was working as a ship plater's labourer; Gladys as a dressmaker. John, the youngest, was still at school. The family lived in Above Town.

Service

By 1913 Samuel was working as a boiler-maker's mate. Perhaps his brothers encouraged him to put this experience to good use in the Navy, because he signed on for twelve years as a Stoker 2nd Class on 7th April 1913. The requirements were not onerous - a man needed to be:

- over 18

- a desirable man for the Service

- fit for the rating

- able to read and write fairly

His pay was 1s 8d per day. Samuel was 5ft 4½ins tall, with light brown hair, blue eyes and a "fresh" complexion. Although giving his age as 18, he was in fact 20.

His first appointment after his training was to the Seventh Destroyer Flotilla, under depot ship Leander, based in Devonport. On 7th April 1914, having completed a year in service, he was rated Stoker 1st Class, having met the technical requirements:

- efficiency as a fireman when boiler is working at full power

- ability to attend and lubricate a bearing

- knowledge of the names and uses of the principal tools in ordinary use in the Engine Room Department

- intelligent use of the more simple ones eg spanner, hammer, chisel, file, screwdriver

- ability to plait gasket for packing

- fair knowledge of the Stokers' Manual

Samuel was appointed to the destroyer HMS Sylvia, operating out of the Humber, and was still there at the outbreak of war. His brother Horace was serving in the battleship HMS Centurion and his brother Reginald in the battleship HMS Thunderer. Both were Seaman Gunners. The names of the three brothers duly appeared in the lists of the men of Dartmouth serving in HM Forces published weekly at that stage of the war in the Dartmouth Chronicle, on 30th October 1914.

According to the Dreadnought Project, HMS Sylvia left the 7th Destroyer Flotilla sometime between October and December 1914, to become one of thirty destroyers attached to the four Battle Squadrons operating in Home and Atlantic waters, and then to the Grand Fleet. But Samuel was not with the Grand Fleet for long. His record shows that he moved from destroyers to submarines, being apppointed on 14th October 1915 to HMS Dolphin, the depot ship for the Portsmouth Defence Flotilla; and then on 10th December 1915 to HMS Maidstone, the depot ship for the Eighth Submarine Flotilla, at Harwich. After a few months at Harwich, he was appointed to HMS Adamant, the depot ship for "Special Service Submarine Flotilla I", in the Mediterranean, on 29th March 1916. His record, however, only names one specific boat, submarine E14, which he joined on 1st July 1917.

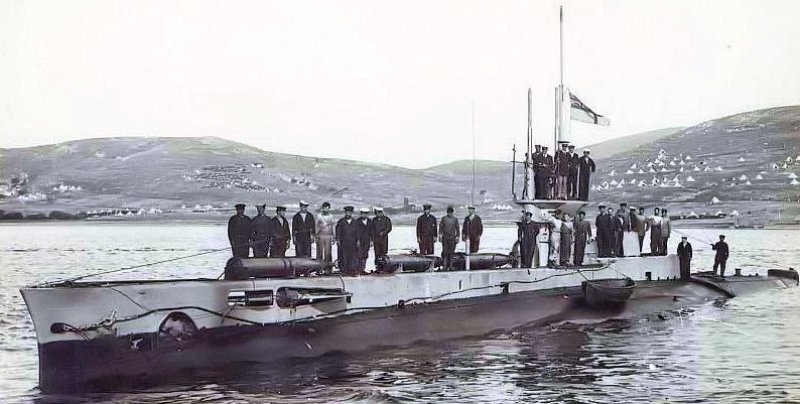

HM Submarine E14

E14 was built at Vickers in Barrow in Furness. She was laid down in December 1912 and commissioned on 18th November 1914. Like the rest of her class, she was an oceangoing submarine, 180 feet long, able to reach a surface speed of 16 knots and 10 knots when submerged; she was able to operate submerged for five hours, when travelling at 5 knots, and her range (at 10 knots) was 3,255 miles. Her maximum design depth was 100 feet (30 metres), though in practice some of the class reached greater depths. She was equipped with ten torpedoes.

In the engine room, Samuel looked after two diesel engines and two electric motors; he was one of a complement of three officers and 28 men. Conditions were extremely cramped and fairly basic - the three officers shared a bunk and the ratings slept where they could. As the submarines were fairly small, they could not carry large quantities of supplies, and so were very dependent on their depot ships to supply their needs when not on patrol.

Submarines in the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles, connecting the Sea of Marmara and the Mediterranean, presented a challenging operational environment for submarines. A deep layer of fresh water moving downstream through the channel, above a band of saltwater moving upstream, created real difficulties when submerged, and when the submarines surfaced, there were mines, nets, enemy patrols, and shore batteries to contend with.

HMS Adamant became the submarine depot ship in the Dardanelles in March 1915, having left Harwich on 27th March 1915 in company with three E class submarines, E11, E14 and E15. On 16th April 1915, E15 attempted to break through to the Sea of Marmara, but was caught in strong currents ten miles into the straits and ran aground. Ottoman guns ashore opened fire and her CO was killed. Chlorine released when the batteries were exposed to seawater forced the crew out to the surface and they were captured. Several attempts were made to ensure that E15 was not salvaged by the enemy, and she was eventually destroyed on the night of 18th April.

The first submarine successfully to force the passage was AE2, one of two E-class submarines ordered for the Royal Australian Navy before the war. Commanded by Lt Cdr Henry Stoker, she left Mudros the day before the Gallipoli landings with orders "to run amok" in the Narrows. Despite being grounded twice, and fired upon each time, she was successful. E14 was ordered to follow her, and she too was able to make the passage, entering the Sea of Marmara on 27th April 1915. The two submarines met in the Sea of Marmara on 29th April 1915. However, AE2 was involved in a collision with an Ottoman torpedo boat, and sank - Henry Stoker and his crew were taken prisoner. E14 was able to sink two gunboats and a large enemy transport. She remained in the Marmara until 18th May. As a result of her exploits, her captain, Lt Cdr Edward Boyle, was awarded the VC, Lt Edward Stanley and Acting Lt Reginald Lawrence were awarded the DSC, and all the ratings were awarded the DSM. E14's example was then followed by further success in the Sea of Marmara by her sister submarine, E11, under Lt Cdr Martin Nasmith, building on the experience gained by AE2 and E14; E11's crew were similarly recognised.

E14 undertook two further patrols in the Sea of Marmara, from 10th June 1915-3rd July 1915, and from 21st July 1915-12th August 1915, by which time she had spent a total of seventy days there. The allied submarine campaign in the Sea of Marmara was one of the few successes (if not the only one) of the Gallipoli campaign. Between April 1915 and January 1916, nine British submarines sank two battleships and one destroyer, five gunboats, nine troop transports, seven supply ships, 35 steamers and 188 assorted smaller vessels at a cost of 8 submarines sunk in the Strait or the Sea of Marmara. As a result, Ottoman forces largely abandoned the sea supply route. Overland transport added costs and delays to their military operations, and severely restricted food supplies to Constantinople itself.

In the middle of 1916, the Royal Navy reorganised the submarine flotillas, but E14 remained in the Mediterranean Flotilla, with her depot ship based in Malta. Lt Cdr Geoffrey Saxton-White took over her command on 10th August 1916. In 1917, E14 was one of four submarines sent to Corfu, where a new base was established to strengthen the Otranto Barrage, the allied naval blockade of the Otranto Straits connecting the Adriatic and Ionian seas. The crew lived in a tented encampment near an old Venetian gun battery. Samuel joined E14 during this period.

SMS Goeben/Yawuz Sultan Selim

On 19th January 1918, the battle cruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau finally broke out of the Dardanelles on a raid of British naval bases. Though officially part of the Ottoman Navy, and renamed the Yawuz Sultan Selim and the Midilli respectively, the ships still retained German crewmembers. They had taken refuge in Constantinople in the early days of the war (see the story of Frederick Santillo) and remained a considerable potential threat to the Eastern Mediterranean. For the action known as the Battle of Imbros, which took place the following day, see the story of George Edward Whitemore, who died when HMS M28 was sunk by Breslau. Breslau sank also, having hit several mines.

Following the engagement, and although damaged, Goeben was still able to make good speed and so reached the safety of the Dardanelles. But due to a navigation error, she ran aground off Nagara Point, north of Chanak (modern Canakkale). For the next six days, RFC and RNAS aircraft, operating from Mudros and Imbros and from aircraft carriers, flew 270 flights, dropping 15 tons of bombs. However, this had little effect - even the official History observed that:

These attacks, though executed with the utmost daring and pertinacity, did practically no damage.

Essentially the problem was that the bombs the aircraft carried were too small to do much damage to a very large battlecruiser, even when direct hits were achieved (on 22nd January, one bomb actually fell down Goeben's after funnel). Bad weather was also a problem.

A small monitor, M17, was then brought in, but weather conditions made spotting of her indirect fire difficult, so this also had no effect. Submarine attack was clearly the next option, but submarine resources were scarce. The only submarine immediately available at Mudros, E12, had a fractured engine shaft, affecting her surface speed (a replacement shaft had been ordered but the ship carrying it had herself been torpedoed and sunk). E2 was in Malta, just completing a dockyard refit; E14, in Corfu, was the nearest fully effective submarine. The remaining two submarines in the Mediterranean were far away, in Gibraltar.

Because of the damage to E12, both E2 and E14 were summoned when the news of the Goeben's sortie came through. Passing through the Corinth canal, E14 reached Mudros from Corfu on 22nd January. E2 arrived shortly afterwards from Malta, though one of her torpedo tubes was still out of action.

Saxton-White, with his colleague from E2, immediately reconnoitred the Goeben from the air, in preparation for any submarine operation, expected imminently. However, by this stage, the failure to deal with Goeben was causing considerable embarrassment to the Admiralty. The Commander in Chief Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral Gough-Calthorpe, was ordered to "use every effort to destroy the Goeben" and was sent to the Aegean to take personal charge. No decision was taken about the use of the submarines until he arrived on 25th January. At the resulting conference, it was decided to send in E14. No British submarine had entered the Dardanelles for two years, and Saxton-White thought he would have the advantage of surprise. Furthermore, his was the only one of the available submarines at full operational efficiency; and he and his crew had an excellent reputation.

The risks of the operation were recognised as considerable, and two days were taken to prepare, including the transfer of all E14's confidential papers to the depot ship. It was decided to attempt entry to the straits at night, even though this made navigation more difficult, and also to mount a diversionary attack on the Goeben before dawn by seaplanes carrying torpedoes. E14 would attack immediately afterwards.

E14 set off from Imbros at 5.0pm on the night of 27th/28th January. But in the meantime, Goeben had finally been refloated, although the considerable effort required had been delayed by the aircraft bombing; and she had been able to reach Constantinople that very day. Luck was with her - gale force winds had prevented any airborne reconnaissance the day before, which would have identified that she had left.

The seaplanes also duly took off, though only one was able to reach the target area; the pilot dropped his torpedo on the Goeben's estimated position, and there was an explosion, but the pilot did not know whether the battlecruiser was still there.

E14 entered the Straits without mishap and, just before dawn, surfaced to try to fix her position. However, she then found herself caught in some sort of obstruction. Saxton-White climbed down on to the bow to give the necessary orders to get the submarine clear, was successful, and the submarine once more dived, having seen two marker buoys indicating the position of a possible channel through the minefield in the Narrows. At about 7.0am, E14 reached Nagara Point, where the Goeben had been, but the battlecruiser had gone. E14 went further up the Straits but could see no sign of her target. She now had to return, in daylight; and due in part to the difficulties she had encountered in freeing herself from the obstruction earlier, her battery was already low.

As she neared Chanak (modern Canakkale), E14 sighted a large merchant ship and fired both her torpedoes. Exactly what then happened is not clear, but 11 seconds later there was a large explosion, close to the submarine. One account states that she was detected by hydrophones and forced to the surface by depth charges; another that the submarine's own torpedo exploded prematurely; another that perhaps the torpedo hit a mine at close range. Either way E14 was blown to the surface by the explosion and the Ottoman shore batteries immediately opened fire on her at short range.

However, she was able to dive once more - at this point, she was damaged but just about controllable, though air supplies and the battery were low. For two hours she continued her dived passage slowly towards the open sea, but things gradually became worse and eventually Saxton-White was forced to order the submarine to surface. When she did so, she was subjected to heavy gunfire from the forts at either side of the entry to the Straits.

To give his crew some chance of escaping, Saxton-White ordered E14 to be turned towards the shore. He remained on deck, and soon afterwards a shell exploded near the conning tower, killing him and his navigating officer, Lt Drew. The submarine began to sink. Some men were able to reach the water, some of whom were wounded, but others were still at their posts. Nine survived and were captured, remaining prisoners of war until the war was over. One of them, Able Seaman Reuben Mitchell RAN (who had previously served in AE2), later wrote the following account of E14's final moments:

After a time, the boat got out of control, and as we had only three bottles of air left, the Captain thought it would be best to surface. At once we could hear heavy fire and we could hear pieces hit the hull of our boat. As a result of a hit in the centre of the boat, it could not dive again. We ran the gauntlet for half an hour under murderous fire from all round, only a few hitting the hull of the boat. Our wireless operator was badly wounded in the mouth and the left hand, and fell unconscious. The Captain, seeing it was hopeless, ran the boat towards shore. His last words were, "We are in the hands of God, my men. Do your best to get ashore".

A few seconds later, I saw his body mangled by shellfire, roll into the water and was taken under. The same shell killed the Navigator and left me by myself, and other shells killed nearly all the hands. Had the Turks stopped firing as soon as they saw us sinking, with a few wounded on deck, many more might have been saved. It must have been half an hour before they put out for us. Amid the cries of wounded men in the water, several voices were heard saying, "Goodbye, goodbye all". Their hands went up and they disappeared for the last time. It was hell; when I look back at that fatal half-hour, it haunts me.

E14 had been unable to send a signal before she sank, but air reconnaissance on the morning of the 28th January noted a submerged object under attack by shore batteries, and also identified that Goeben had disappeared, though with no trace of any wreckage. A further flight over Constantinople on 29th January confirmed that Goeben had survived, and worse, that she might even be capable of coming out again (in fact, although she was repaired, she did not enter the Mediterranean again during the war). In the subsequent search for someone to blame for a catalogue of failures, the Admiralty removed Rear Admiral Hayes-Sadler, commanding the Aegean Squadron, from his post.

Death

Samuel was one of 23 officers and crew who died when E14 sank. News of the loss of the submarine appeared in English newspapers soon afterwards, but there were also Turkish reports of a small number of men having been saved, without any names given.

On 7th February 1918 the Western Morning News carried the names of seven members of the crew of E14, including Samuel, as "missing". It was not until 19th April 1918 that the Dartmouth Chronicle reported his death, in an announcement placed by his parents:

Deaths

In loving memory of our dear son Samuel Henry, aged 24 years, second son of George and Louisa Ball, of 2 Jessamine Cottages, Above Town, who lost his life through the sinking of HM Submarine ----, in the Dardanelles, January 28th 1918.

Until the day break and the shadows flee away.

The full circumstances of the loss did not emerge until the members of the crew taken prisoner had been repatriated after the Armistice. In 1919, Geoffrey Saxton-White was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross - the fourth submarine Victoria Cross of the First World War in the Dardanelles. E14 is the only vessel in the history of the Royal Navy in which two commanding officers have won the Victoria Cross.

Reuben Mitchell received the DSM, as did Petty Officer Robert Perkins and Signaller Timbrell. Signaller Pritchard was awarded a bar to his DSM.

Commemoration

Samuel is one of over 7,200 naval personnel lost at sea who are commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial.

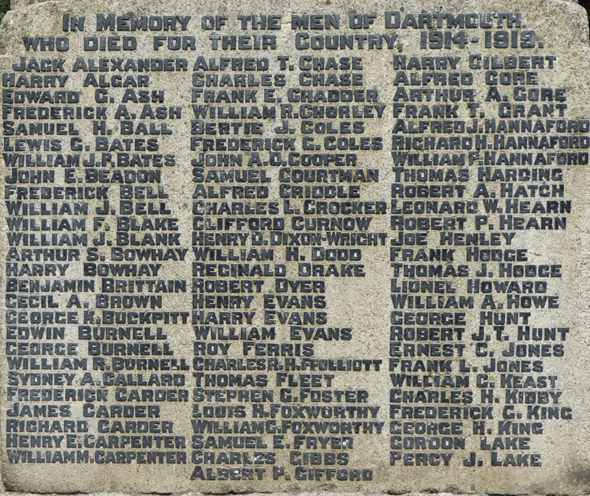

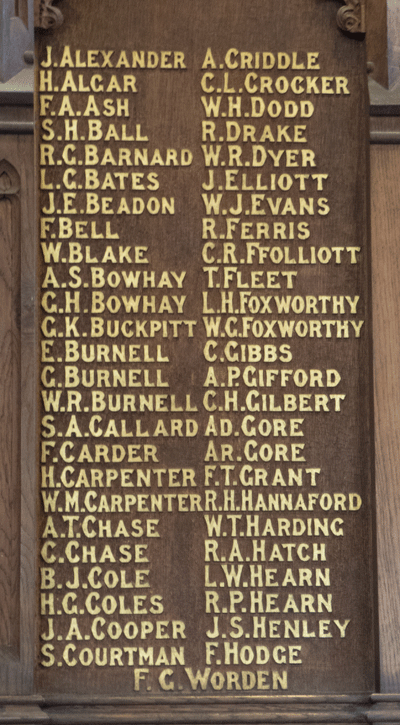

In Dartmouth, he is commemorated on the Town War Memorial and the St Saviours Memorial Board.

Samuel's brothers, Horace and Reginald, both served in the Royal Navy throughout the war, and survived.

The wreck of the E14 was found in 2012 and will now benefit from protection under the UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage.

Sources

Naval service records from the National Archives, fee payable for download, references:

- Samuel Henry Ball: ADM 188/904/18809

- Horace George Ball: ADM 188/423/238157

- Reginald Ball: ADM 188/654/3551 and ADM 363/256/120

Submarines in the Dardanelles, 1915, Australian Government Department of Veterans' Affairs

Australian Submarines: A History, Volume II, by Michael White, pub 2015, Australian Teachers of Media

Reuben Mitchell DSM RAN, Naval Historical Society of Australia

Submariners VC, by William Jameson, pub 1962, republished 2004 Periscope Publishing

Superior Force, Ch 19, The Last Sortie, by Geoffrey Miller, available online

Harwick and Dovercourt: Submarines World War I

History of the Great War, Naval Operations, Vol V, by Henry Newbolt, pub Longmans 1931, accessed online

Casualty and prisoner of war figures for E14 from naval-history.net

Underwater Cultural Heritage from World War 1, Proceedings of the Scientific Conference 26th & 27th June 2014, published 2015, UNESCO

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Ball |

| Forenames: | Samuel Henry |

| Rank: | Stoker 1st Class RN |

| Service Number: | K/18809 |

| Military Unit: | HM Submarine E14 |

| Date of Death: | 28 Jan 1918 |

| Age at Death: | 25 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Dardanelles |

| Place of Death: | Dardanelles |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated on Plymouth Naval Memorial |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Plymouth Naval Memorial |