Cyril Francis Stafford

Cyril Francis Stafford was neither born in Dartmouth nor, so far as we have been able to establish, did he live there. He most probably appears on Dartmouth's town War Memorial because his mother came from the town, and two of her sisters lived there.

Family

Cyril Francis Stafford was born in 1895 in the district of West Ham, Essex. He was the only surviving son of Francis Bernadine Stafford and his wife, Bessie Bourne Langdon.

Francis Bernadine Stafford came originally from Avon Dassett, Warwickshire, where he was born, but by the time of the 1881 Census his family had moved to Great Malvern, where his father, William Stafford, was a Brewery foreman and agent. Francis himself had left home to work in London, where the same Census shows that he was one of two Footmen in the household of Lord Alexander Gordon-Lennox, in 21 Pont Street.

In 1890, he married Bessie Bourne Langdon, from Dartmouth. Bessie was the fourth daughter of Henry Langdon, who described himself at different times both as a Baker and Basketmaker, and his wife Anna Bourne, from Harberton. By the time Bessie is first recorded in Census records, in 1871, aged 9, the family lived in Broadstone.

In 1881, Bessie was no longer living at home with her mother and father in Broadstone, but with her eldest sister, Anna, nearby in New Road. Anna had married Mark Whittle in 1867. He was born in Dodbrooke, Kingsbridge, but had come to Dartmouth to work for his uncle, Mark Fox, who ran a grocery and wine business on the Quay, and was a councillor. By 1881, Mark and Anna Whittle were running the Commercial Hotel, and Mark Whittle was becoming increasingly prominent in the town, representing Dartmouth on the Totnes Board of Guardians (a role he continued for forty years), and active in several other local organisations.

How Bessie and Francis met is not known - perhaps Francis came to Dartmouth on a visit and stayed at the Hotel. Francis was a Catholic, and he and Bessie were married at the Catholic Church in Willesden on 4th September 1890. The 1891 Census shows them living in the City of London, at Blue Hart Court, Coleman Street, where Francis was the caretaker or concierge for Copthall Buildings. Bessie's cousin Emily was visiting them at the time.

They were not in the City for long, however, for Bessie and Francis' first child, Agnes Bernardine, was born in Brixton in 1892. By the time of Cyril's birth in 1895, they were living in West Ham, where the couple's third child, John William was also born, in 1898. Sadly he died later that year, aged only 3 months. Francis Bernardine Stafford appears in Kelly's Directory for that year as a Beer retailer, at 352 High Road, Tottenham.

The 1901 Census found the family back in central London, in Goswell Road. Francis now worked as a rent collector, and the family also took boarders: the Census recorded two, both working as clerks. The 1903 Electoral Register shows additionally that Francis and his family occupied the house by virtue of his employment.

On 30th December 1904, when Cyril was only nine, his father died, aged only 40. This must have meant that the family had to move, but Bessie remained in London, perhaps because of Cyril's schooling. In 1911, Bessie, Agnes and Cyril were recorded at 59 Cranwich Road, Stamford Hill. Cyril, now aged 16, was at "College". From a very brief newspaper mention, listing boys who had passed the Oxford Local Examinations in 1909, it would appear that he attended St Ignatius College, Stamford Hill.

According to the London Electoral Registers, Bessie (and so therefore most probably Agnes and Cyril too) was still living at 59 Cranwich Road in 1914. (Although women were not able to vote in parliamentary elections, they were able to vote in county elections if they were ratepayers). Cyril was recorded at the same address at the time of his death in 1917.

Service

It seems that, on leaving school, Cyril had joined the Civil Service, for various records indicate that he volunteered for military service soon after the outbreak of war, joining the 15th Battalion London Regiment, otherwise known as the Prince of Wales' Own Civil Service Rifles. The 15th Battalion was one of 26 battalions of the London Regiment of the Territorial Force. It was formed of Civil Servants living and working in London. In August 1914 they were mobilised and brought up to strength by wartime recruits, but so many others volunteered that a second battalion was raised; the originals became the 1st/15th Battalion and the new one, the 2nd/15th, with a 3rd/15th providing replacements for the other two.

The Medal Roll of the 15th Battalion London Regiment shows Cyril as 2929 Private Cyril Francis Stafford and records that he served in France from June 1916 to August 1916; this, together with his service number, suggests that he joined up sometime between 1st September and 7th October 1914 and that he joined the 2nd/15th, going to France with them in June 1916.

The 2nd/15th Battalion's War Diary begins on 4th January 1915, when they left White City, London, for training in Dorking. By 22nd February they were back in London, where they were billetted in their homes for a week, whilst carrying out route marches during the day "with a view to recruiting" and exercised in Hyde Park and Regents Park. They returned to Dorking on 28th February to continue their training, moving to Watford on 30th March and then in May to Saffron Walden, where they moved into tents.

Training continued over the summer; a large draft was sent to reinforce the 1st/15th Battalion, which had gone to France in March 1915. The War Diary reported some excitement when a "hostile airship ... of the Zeppelin type" approached the camp. The men were turned out and "scattered to the special alarm posts". However, the airship just flew over the parade ground and disappeared to the north-east.

With the approach of winter, they were moved out of the tented camp in October to billets near Bishops Stortford, where they remained for most of November, during which the War Diary reported "nothing of interest" on many days. At the end of November, they moved to Ware and began a programme of exercises in which they were required to prevent an invasion of London from various directions.

Evidently the Battalion was not yet up to strength, which may account for the long training period; but on 12th January 1916, 6 officers and 249 recruits arrived from 3rd/15th Battalion, and on 22nd January 1916 all went by train to Warminster to a camp at Longbridge Deverell. Here, on 31st January 1916, the 60th (London) Division was inspected by Field Marshal Viscount John French, Commander in Chief Home Forces. The War Diary reported that the strength on parade was 30 officers and 712 other ranks.

Divisional training then continued during February and March, followed by musketry training in April. On 28th April, the Battalion received orders to move - but not to France. Instead, the Brigade was bound for Ireland, where the Easter Rising had begun four days earlier. However, by the time they arrived at Queenstown (now Cobh) on 2nd May, the Rising was over, though Ireland remained under martial law. The Brigade went into barracks at Ballincollig, west of Cork, and then into camp in the town of Macroom. Having trained for trench warfare against the Germans, the Battalion found themselves instead doing house-to-house searches of their fellow citizens on 9th May. The War Diary reports only that three arrests were made.

But their time in Ireland was brief. On 11th May, they were ordered to return to England, by way of Rosslare and Fishguard. They were back in camp at Longbridge Deverell for church parade on 14th May; and resumed their normal training. On 31st May, they were inspected by the King; finally, they were to go to France. Embarkation leave was given in groups over the next few days; they left Warminster by train on 22nd June and embarked at Southampton, arrriving at Le Havre early the following morning.

By 29th June, they were in the trenches near Maroeuil, north-west of Arras, undergoing trench instruction for real - they sustained their first casualties on 1st July, when one man was killed and two wounded. After six days, they moved back into billets in Neuville St Vaast, north of Arras (at that time, a relatively quiet sector of the line).

The Battalion began its first full tour in the front line on 15th July, going into support trenches on 19th July and back into the front line on 27th July until 4th August. However, it seems that Cyril's experience of the front line as a private soldier was limited to this tour, for the Regimental Medal Roll records that his service in France ended on 4th August, the day on which the Battalion moved to billets for eight days rest. He had been withdrawn for officer training, and was on his way back to England.

Cyril completed his officer training successfully, being commissioned as a 2nd Lt and transferring to the Royal Fusiliers on 22nd November 1916. He was posted to the 24th Battalion, known as the second Sportsman's Battalion. This was raised in London but included several Dartmouth men due to a recruiting drive in the West Country - see the story of William John Bell.

The 24th had gone to France in November 1915; they had served in the Arras sector and had gone to the Somme on 20th July 1916. There they had fought at Delville Wood and in the Battle of the Ancre in November. They had spent December well to the rear of the line, north-west of Abbeville, resting and training and playing a great deal of Brigade football, but by the middle of January had returned to the front line on the Somme near Courcelette, on the Albert-Bapaume road. Cyril's name first appears in the 24th Battalion Royal Fusiliers War Diary on 4th February 1917, when he is listed in Battalion Orders as in charge of a permanent working party of 25 men, prior to the Battalion's return to the trenches near Courcelette the following day. Unfortunately there is no detail in the War Diary or its attached notes of what his working party was doing.

The War Diary suggests that the principal preoccupation at this time was less the enemy than the weather, which was extremely cold - the coldest winter in Europe for many years - and taking all necessary precautions to prevent trench foot, including attention to ensuring gum boots were in good condition, and that there was proper foot care. The tour lasted until 15th February, after which they were in billets in and around Albert, providing large working parties on a daily basis for several different tasks.

When they returned to the front on 27th February, however, the Germans had begun the early stages of their withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line and the Battalion was facing a significantly different situation. Their position, when they moved forward, took them to a new front line in Gallwitz Switch Trench; and Battalion Orders included a warning about booby-traps left by the enemy to trap unwary souvenir hunters:

Great care must be taken in handling any articles left behind by the enemy. Already the Battalion on our right has found a German helmet which, when picked up, set off a bomb and blew a man's hand off.

The main German retirement took place on 16th March and took three days. During that period the 24th Battalion was in billets, but on 19th March they "moved up during the morning to dig trenches south of the Bihucourt-Biefvillers-les-Bapaume line, lately evacuated by the enemy". More or less as soon as they got there they were ordered to return to their camp, but did not arrive until 3.30am "due to congestion on the roads". The War Diary does not explicitly say so, but the process of moving the British army forward to follow-up the German withdrawal produced huge traffic jams, partly because roads had been blocked with trees and mines; but also because, after years of stalemate on the front line, there was little experience of organising rapid forward movement en masse.

The new circumstances meant that 24th Battalion's time on the Somme was over. They were ordered north to the build-up for the new spring offensive at Arras. On 30th March 1917, having marched for several days, they arrived in billets at Cauchy-a-la-Tour, north west of Arras. Cyril thus found himself back in the sector where he had spent the few short weeks of his previous front-line service, only a few months before.

The Battle of Arras

During the freezing winter of 1916/1917, there had been a number of significant casualties amongst the Allies' top decision-makers. On 13th December 1916, General Joffre had been dismissed as Commander in Chief of French forces, being promoted to Marshal of France, but sidelined to an essentially advisory role (from which he quickly resigned). His replacement as Commander in Chief of French Forces on the Western Front was Robert Nivelle, who had led the successful French counter-offensive at Verdun.

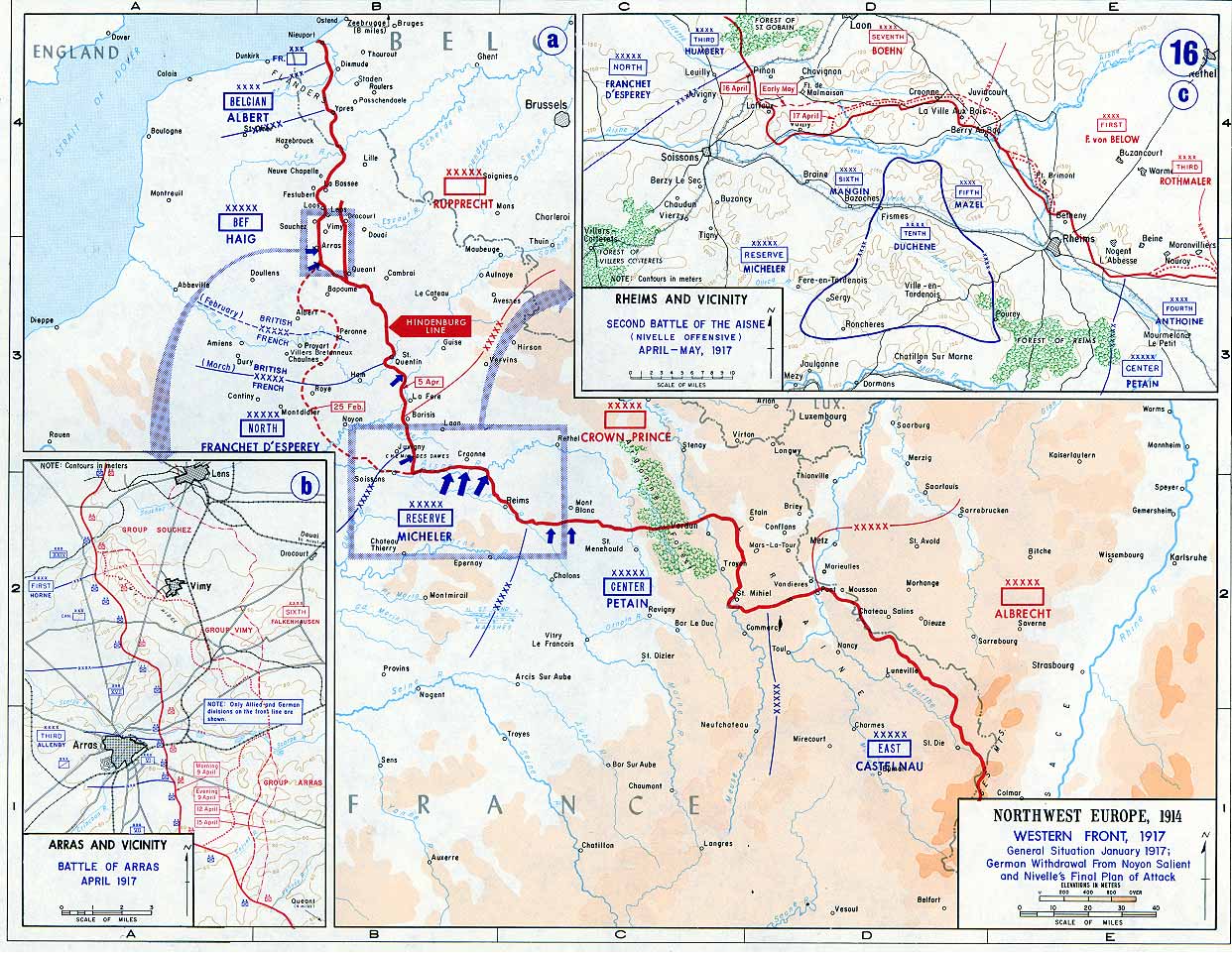

Only a week before, the Asquith Coalition had collapsed in Britain, and David Lloyd George had taken over as Prime Minister. Lloyd George was deeply critical of the outcome of the Somme, wanting to pursue any alternative to continued fighting on the Western Front, and very distrustful of his senior generals. But General Nivelle persuaded him that a preliminary diversionary British attack near Arras, large enough to bring in German reserves from further south, and swiftly followed by a huge French offensive to the south against the Chemin des Dames Ridge, behind the River Aisne, would achieve the longed-for breakthrough to final victory. So much so, that he put General Haig under General Nivelle's command for the duration of the campaign (his original proposal went rather further in integrating the command structure, but had to be watered down).

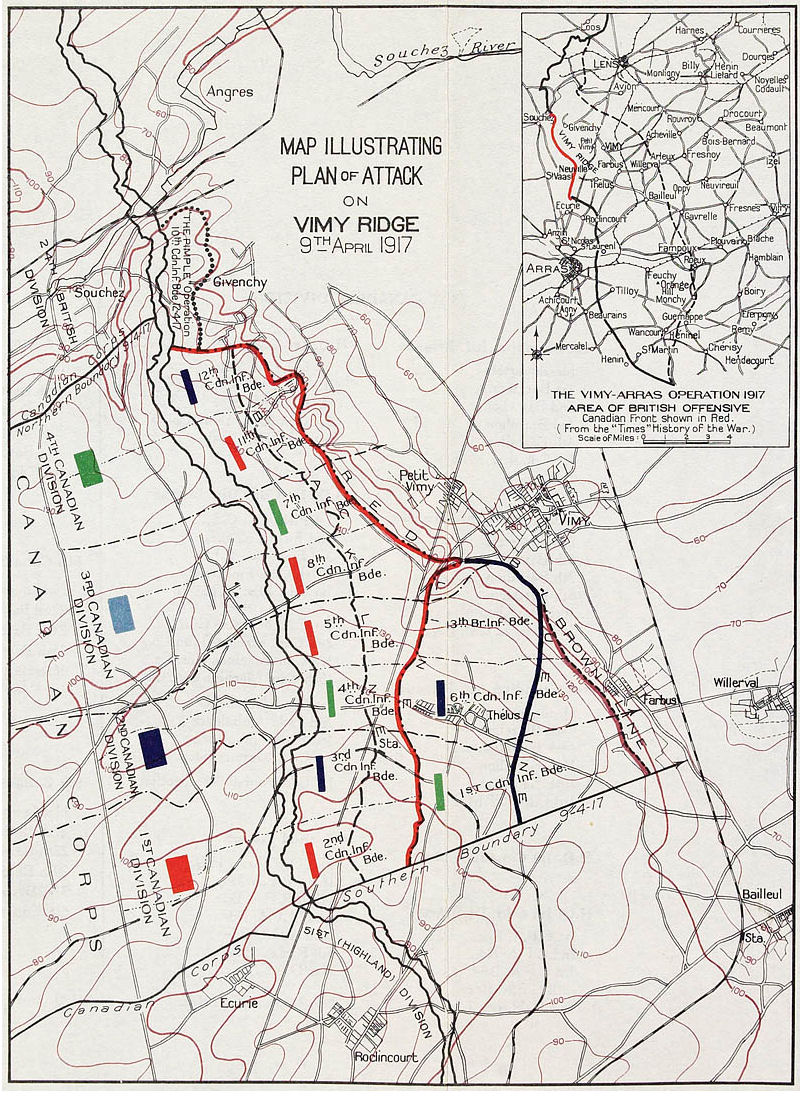

The Battle of Arras, though envisaged as a "diversionary" operation, was nonetheless a huge undertaking. Third Army, under General Allenby, was planned to attack along a ten-mile front to the north and south of Arras, with the aim of breaking through the main German defensive lines either side of the River Scarpe and allowing a push southwards; immediately to the north of Allenby, part of First Army, under General Horne, including the Canadian Corps, was planned to attack Vimy Ridge.

Artillery was vital to the plan and a vast array of firepower was brought up: 2817 guns, 863 of heavy or medium calibre, delivering more than 50,000 tons of shells, faced only 1014 German guns. Fewer shells were duds and the more sensitive "106" fuses made shells more effective in clearing barbed wire. The creeping barrage incorporated not only high explosive and shrapnel but also smoke and gas. Artillery observation flights allowed gunnery to be corrected and accuracy improved, and photographic flights provided rapid information about damage; the RFC aimed to dominate the air above the battle and for twenty miles beyond it - though at heavy cost. In addition, mines were dug under German positions and extensive tunnels under Arras protected many of the assaulting troops as they assembled for the attack.

A preliminary bombardment began three weeks before the attack and the bombardment intensified in the four days immediately prior. The infantry attack began at 5.30am on 9th April. On the main part of Vimy Ridge, the attack by the Canadian Corps was a resounding success. The first two lines of German trenches were virtually obliterated by the artillery barrage; and there was no time for the Germans to bring up reinforcements before the position on the Ridge was consolidated. Over the next three days the eastern slopes of the Vimy Ridge were secured. By 12th April a small fortified hill at the northern end of Vimy Ridge, called The Pimple, which had initially resisted capture, had been taken, and the front line had advanced to the far side of the reverse slope of the ridge, reaching the village of Farbus.

On 11th April, the attack was renewed, and the village of Monchy-le-Preux, close to the Arras-Cambrai road, was captured after very heavy fighting. However, the heavily defended village of Roeux, on the Arras-Douai railway, where an old Chemical Works provided an apparently unassailable position, remained untaken (it did not finally fall until 11th May).

The 24th Battalion Royal Fusiliers, along with most of the rest of 2nd Division, though part of First Army, were not part of the attack. They were in reserve at the start of the battle, with instructions to be prepared to move at four hours' notice after "zero" hour on "Z" day, as the day of the attack was called. On 8th April, they were brought forward, leaving Cauchy-a-la-Tour to march to La Comte, a few miles nearer Arras. At midnight on 9th/10th April, the 2nd Division received orders to move the following day to the Maroeil area, preparatory to relieving the 51st Division, which had attacked the south end of Vimy Ridge alongside the Canadians. On 10th April, therefore, they marched to camp west of Maroeuil Wood, to the north-west of Arras. By this time, it was once again extremely cold, with frequent heavy snow and sleet showers.

Death

On 11th April, the 24th Battalion arrived in the front line at Farbus, a village below the eastern slopes of the Vimy Ridge. The War Diary reported:

Relieved the 9th Royal Scots in front line ... Battalion on our right 1st KRRC, Battalion on our left 8th Canadian Infantry. A heavy snowstorm fell in the afternoon and evening.

On 12th April 1917, the War Diary recorded no enemy activity, only the continuing bad weather - "very wet, with snow and sleet showers".

On 13th April 1917 the 24th Battalion's neighbours, the Kings Royal Rifles, had sent out a patrol across the line and had discovered that German defences on the embankment of the Arras-Lens railway, running north-south just in front of the British line, were unoccupied. At 3pm the 24th were ordered to move forward across the whole Battalion front towards the village of Willerval (on the right hand edge of the map above):

The 1st objective being the railway line and the second a line from [the eastern] edge of Willerval to that of Bailleul [to the south], covering the Sugar Factory, midway between [the two villages]. At 5pm the leading waves advanced, and reached both objectives, under heavy artillery fire, from which C Coy on the left suffered most severely. 30 or 40 Germans were seen to leave the Sugar Factory as our line approached it. A line of posts was dug on the second objective, where the Battalion remained for the night. A German naval 6-inch gun was captured in an orchard at the Sugar Factory.

The following day the War Diary records:

At 1pm orders were received to press forward and gain touch with the enemy and dig in. At 3pm Battn moved forward on whole front and advanced to 500-600 yards from Arleux-en-Gohelle [to] Oppy line, and dug in a front and support line of posts under heavy artillery and machine gun fire, the flanks being bent back to maintain contact with troops on either flank, who had not moved. Relieved that night by 2nd Oxf & Bucks LI and proceeded to dug-outs in old British and German front lines, arriving on morning of 15th April. Weather wet, snow and sleet".

Cyril was one of three officers listed in the Battalion War Diary as wounded in the action on 13th April 1917; the diary's summary of Officer Casualties in April further notes beside his name "since died of wounds". One officer was killed. Amongst the men, four were killed, 17 were wounded, and one was missing.

It would seem that Cyril was evacuated from the battlefield but died the following day whilst being cared for in the field ambulance unit; he was buried in Haute-Avesnes British Cemetery, nine kilometres west of Arras.

Commemoration

As one of the 579,206 casualties in the region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Cyril is commemorated on the new memorial at Notre Dame de Lorette, "The Ring of Memory".

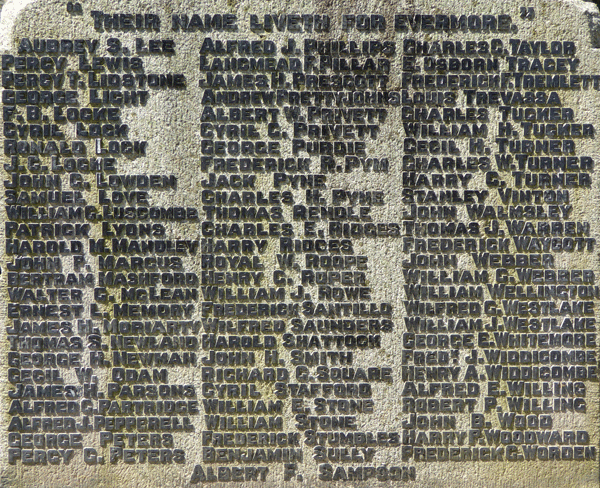

Cyril is also commemorated on the Town War Memorial in Dartmouth. His mother does not seem to have returned to the town - she continued to live in Stamford Hill, in later life making a home with her daughter, Agnes, who had married in 1921. However, Cyril's aunt, Anna Bourne Whittle, remained in Dartmouth - her husband Mark had died in 1912; as did her youngest sister Clara, who had married Alfred Kendall in 1893. This may explain the inclusion of his name on the Dartmouth War Memorial.

Cyril, his father and mother, and his baby brother Jack, are all commemorated on a private family memorial in St Patrick's Roman Catholic Cemetery Leytonstone.

Sources

War Diary of 2nd/15th Battalion London Regiment 4th January 1915 to 30th November 1916, available at the National Archives, fee payable for download, reference WO 95/3030

War Diary of 24th Battalion Royal Fusiliers 8th November 1915 to 31st March 1919, available at the National Archives, fee payable for download, reference WO 95/1349

The History of the Second Division 1914-1918, Volume 2, Everard Wyrall, publ Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1918

Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras 1917, by Jonathan Nicholls, publ Pen & Sword 2005, reprinted 2015

The Great War, by Peter Hart, publ Profile Books, 2014

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Stafford |

| Forenames: | Cyril Francis |

| Rank: | 2nd Lieutenant |

| Service Number: | 2929 |

| Military Unit: | 24th Bn Royal Fusiliers |

| Date of Death: | 14 Apr 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 22 |

| Cause of Death: | Died of wounds |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of Arras |

| Place of Death: | Haute-Avesnes, France |

| Place of Burial: | Buried Haute Avesnes Cemetery, near Arras, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | No |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |