William John Bell

Family

William John Bell was born in 1886 in Kingswear, Devon. He was the eldest son of John Amos Bell and his wife, Sarah Elizabeth Wills.

John was born and brought up in Dartmouth. His father Edward Alford Bell worked as a mason and shipwright. He died in 1871, when John was only six. John and his brothers were all baptised in St Saviour's, Dartmouth, on 21st March 1872, a few months after their father's early death (see also the story of Frederick Thomas Bell, the son of John's younger brother Frederick).

John's mother Elizabeth remarried in 1878. Her second husband, Samuel Callard, worked as a labourer. He was widowed, with a daughter, Minnie. Elizabeth and Samuel had two children, Charles Samuel, and Sydney Abraham, 5 months old at the time of the 1881 Census. Sydney Abraham Callard is also on our database). The family lived in Oxford Slip, close to the river. John, aged 16, worked as an agricultural labourer.

In 1886, John married Sarah Elizabeth Wills, who was also born in Dartmouth. She was the eldest daughter of Robert Wills, a sailor, and his wife Anna Browse. By the time of the 1881 Census, however, she was living with her paternal grandparents, in Strete, where she worked as a domestic servant. John and Sarah appear first to have lived in Kingswear - both William and his younger brother Frederick Gilbert (known as Gilbert) were born there. But at the time of the 1891 Census, they lived in Crowther's Hill, Dartmouth, next door to Sarah's father, Robert, and younger brother Frederick.

In that Census, John's occupation was shown as "laundryman". It seems likely that he had already gone to work at the Dartmouth and Kingswear Steam Laundry, since by the time of the 1901 Census, he was the foreman there. He and his family lived at Laundry Cottages - the picture below must have taken at about that time. The Laundry was located at Waterhead Creek, Kingswear. It was originally built as Pope's Brass and Iron Foundry in 1866 before becoming Polyblank's Shipbuilders and Engineers in 1874. George H Mitchelmore (1841-1919) took over the building in 1884 after his previous property in Dartmouth was destroyed by fire, and reopened it with the latest laundry machinery as the Dartmouth and Kingswear Steam Laundry.

By 1901, William and Gilbert had five younger brothers and sisters: May, aged 8; Wilfred Cyril (known as Cyril), aged 7; Irene, aged 4; Olive, aged 2; and Leslie, aged 11 months. William had attended Kingswear school, but by this time had started his working life, as an errand boy for the Post Office.

He soon moved on to other work. On 26th July 1902, he joined HMS Britannia as a Domestic 3rd Class, giving his date of birth as 26th July 1886, though in all probability he was not quite 16 years of age (his birth was not registered until the last quarter of 1886). His naval service record states that he was 5ft 2ins tall, with dark brown hair, hazel eyes and a "dark" complexion. Prior to joining the Navy, he had been a baker's assistant.

HMS Britannia was at this point still based in the old sailing ships in the River Dart - the new College building had begun (the foundation stone was laid on 2nd March 1902) but was not completed until 1905. HMS Britannia was a key client of the Steam Laundry, so links between the Navy and the family must have been strong.

William served for five years. After spending his first few months in HMS Britannia, he was sent to HMS Exmouth, a new "Duncan" class battleship which commissioned at Chatham on 2nd June 1903 for service in the Mediterranean Fleet. William joined her the following day as a Domestic 3rd Class. In May 1904 she returned to the UK and recommissioned as Flagship of the Vice Admiral of the Home Fleet. William left her for a few weeks leave and then joined HMS Lion, an old training ship at Devonport, followed by six weeks in early 1905 in HMS Barfleur, which was nearing the end of her refit. When Barfleur left for China, William was sent to Empress of India, also undergoing refit, and remained with her when she returned to the Reserve Fleet. He left the Navy on 18th August 1907, aged 21. Shortly before he left the service, William's younger brother Gilbert entered; he joined as a Boy 2nd Class on 3rd June 1907 and signed on the following year for twelve years service.

By the time of the 1911 Census William was back in the Royal Naval College (which had by then been completed) working as a Cook - it would seem, as a civilian. John and Sarah Bell, meanwhile, continued to run the Steam Laundry; and two more little boys had joined the family, Rodney and Reginald.

In 1913, William married Rosetta Hooper. She was one of twelve children of Francis Hooper, a stone mason, and his wife Mary Anne Kemp. Francis was a stonemason at granite works in Moretonhampstead. Rosetta had been born in Linkinhorne, Cornwall; she and her family had moved to Moretonhampstead when she was about seven. At the time of the 1911 Census, she was still living with her parents and younger brothers and sisters in Moretonhampstead, and working in domestic service as a cook. Perhaps it was this shared occupation that brought William and Rosetta together.

William and Rosetta had one child, Gilbert John, born on 25th May 1915, after William had joined up, but while he was still undergoing training in England - so perhaps he was able to see his son before he went overseas.

Service

William's service papers, like so many, have not survived. However, his name, and that of his younger brother Cyril, appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle on 26th February 1915 in a list of names of those from Kingswear serving in the Forces (the newspaper recorded weekly those joining up or already serving under the heading "Roll of Honour"). They both joined the 24th Battalion Royal Fusiliers, known as the second Sportsman's Battalion, having consecutive service numbers: Cyril was 3129 and William, 3130. Comparison of these service numbers with the numbers of those whose service papers have survived indicates that William and Cyril attested sometime between 10th February and 6th March 1915. This is broadly consistent with information given in the Dartmouth Chronicle at the time of his death, which stated that he had joined the Battalion on 8th February 1915. The choice of regiment may seem odd at first sight, for since 1881 the Royal Fusiliers had been the City of London Regiment. However, several men from Dartmouth joined the Sportsman's Battalion, following a recruitment campaign in Devon.

The 23rd and 24th Battalions Royal Fusiliers were recruited following the outbreak of war, as the result of a private initiative by Emma Cunliffe-Owen, a well-off "society lady". It is said that when she asked a group of her male friends why they had not yet joined up, they said they had been rejected because they were over age, and challenged her to raise a battalion of her own which would take them. So she sent a telegram to Lord Kitchener:

"Will you accept complete battalion of middle and upper-class men, physically fit, able to shoot and ride, up to the age of 45?"

The reply was: "Lord Kitchener gratefully accepts complete battalion."

Emma Cunliffe-Owen and her husband Philip hired the India Room at the Hotel Cecil on the Strand in London, and found twelve retired army men to act as recruiting officers. Adverts were placed in newspapers and recruiting events held all over the country. The First Sportsman's Battalion was recruited in four weeks, and so effective was the recruiting campaign that a Second Battalion was sanctioned by the War Office on 21st November 1914; attestations for the second Battalion began three days later.

On 7th December 1914, Captain A E Dunn, past Mayor of Exeter and past MP for Cambourne, began recruiting in Devon. Further recruiting took place in Devon and Exeter on 15th January 1915. The Dartmouth Chronicle of 29th January 1915 reported:

The Sportsman's Battalion

There are already Dartmouth men in the Sportsman's Battalion and more will be welcomed. During the last few weeks Lt Dunn, better known in the West as a past Mayor of Exeter and an ex-Member of Parliament for Cambourne, has been organizing a complete West-country company. Already out of the 250 men required over 150 men have enrolled themselves. Lt Dunn has organized the platoons on Territorial lines. There is a Cornish platoon, Plymouth Platoon, an Exeter Platoon, and last but certainly not least, a Devon County Platoon, composed of men from outside Plymouth and Exeter. This platoon is rapidly filling, but at present there is room for more. Here is a glorious opportunity for the men of Devon to show the metal of which they are made.

The timing of their attestation indicates that William and Cyril enlisted during this recruiting drive. Notwithstanding the original advertisement calling for "middle and upper class men", the Sportsman's Battalions were "cosmopolitan … every grade of life was represented, from the peer to the peasant", and included authors, artists, clergymen, engineers, actors, and archaeologists, as well as sportsmen. The Western Times commented that:

The character of the battalion has attracted recruits quite as much as the extension made by the War Office in the age limit.

William was about 28 at the time, towards the upper end of the recruitment age (19-30); perhaps it was indeed "the character of the battalion" that drew him to it. It is not known if he had a particular sporting connection. However, another member of the battalion was Alfred John Westlake, brother of James Westlake and Wilfred Westlake. Alfred also worked at the Royal Naval College, suggesting there may have been a recruitment focus through the College.

The "C" or "West-Country" Company of the 24th Battalion, while recruitment was going on, were temporarily headquartered in Exeter. On 16th March 1915, at 8am, they left the city for London, marching from St Sidwell's to Exeter St David's station through cheering crowds. The Western Times observed:

No one who saw the Battalion - fresh, smart, athletic and fit as the men are - march through the City with that litheness and swing which betokens perfect physical fitness and vigour, could help congratulating Capt. Dunn on having the proud command of such a splendid body of men.

The newspaper reported that there were 323 men of all ranks.

The following day, the full Battalion was inspected on Horse Guards parade and Emma Cunliffe-Owen was requested to take the salute. After responsibility for the two Battalions was handed over to the War Office in 1915, she continued to take an active interest, writing to every sick and wounded man and visiting many in hospital. Two days later the Battalion moved to new headquarters at Hare Hall, Romford, Essex. The Cunliffe-Owens had provided them with "the most up to date field barracks yet erected", according to the Chelmsford Chronicle. Beds turned to the wall during the day provided seats; there was electric light; there were sufficient shower baths, with hot and cold water; there was a hospital with 24 beds; plus a bootmaker, post office, tailor and barber.

In June they came under command of 99th Brigade, in the 2nd Division, and moved to Clipstone Camp, Nottinghamshire; and in July they moved to Tidworth Army Camp, Wiltshire. Also at Clipstone and Tidworth at the same time was Robert Prowse Hearn, a member of 22nd (Kensington) Battalion Royal Fusiliers.

The 24th Battalion's War Diary begins at Tidmouth on 8th November 1915. They departed for France a week later, arriving in Le Havre on 16th November.

On 28th November, having arrived at Annequin for their instruction in trench warfare, the Battalion transferred within the 2nd Division from 99th Brigade to 5th Brigade. In December, they were in the line near Bethune. The War Diary appears to be missing most of the pages for that month, but William's colleague Alfred John Westlake sent a letter on 5th January 1916 to the Dartmouth Chronicle, describing their early experiences, which was published in the paper shortly afterward.

Within a fortnight of our landing we had our first taste of the trenches ... To get to the entrance of the communication trenches from the billets we had to pass through a fair size village, which had been almost entirely destroyed by shell fire. What a sight it was! It was this awful spectacle and evidence of German methods of warfare, coupled with the continual roar of the guns around us that opened our eyes to ... war and its horrors. We soon got over the first shock of the roar of the guns, which we were told were simply carrying on the usual "quiet day" and keeping the Huns on the qui vive. What a heavy bombardment was like we did not desire to know at the moment!

Arriving at ... the communication trenches we were actually "in the soup" for we had not gone far toward the support trenches before Fritz sent over a little reception in the shape of a whizzbang, which set our nerves tingling and sent our heads below the parapet. Through mud and water up to our knees for about half-a-mile brought us to the reserve trenches some three hundred yards in front of the German front line. To be so close to our friends the enemy for the first time naturally made some of us curious to see what the front was like! One peep over the parapet was quite sufficient, for we were greeted by a hail of snipers' bullets. A quiet chuckle from our companions of a regular regiment at our evident newness brought us to our senses, and we set to work with our spades and pickaxes - thinking hard.

It is surprising how quickly one gets used to the continuous shellfire, and in a few days we reckoned ourselves amongst the cool-headed "veterans". One soon learns to distinguish between the shrill note of the light but dangerous whizzbang, and the heavier shells known as "coal boxes" and "Jack Johnsons" used by the Germans, and consequently to give them each due respect, according to their proximity to one's dug-out or duty post. It is impossible to run into safety from a shell: the only thing to do is to duck, or even fall flat in the bottom of the trench. This practice soon becomes second nature. Trench mortars are spiteful little creatures to deal with, for they are thrown high into the air and drop (if well aimed) right into an opposing trench and explode with a loud detonation, and have effect over a considerable distance, but there is this advantage; one can hear these customers coming, and therefore one is able to make oneself scarce. Snipers' bullets are treated with contempt - as long as one's head is below the parapet.

From the stand to at dawn throughout the twenty four hours day in and day out, a constant watch is kept on Fritz's movement, and our artillery also has the enemy well in hand. To relieve the monotony of the day (for there are few Germans who show themselves for target practice) a little novelty is given us in the shape of aeroplane duels, and in this department our aviators hold the upper hand. The most trying experience our company had was on the night before Christmas Eve when (with another battalion) we were in the firing line at the time the German artillery commenced a very heavy bombardment of our trenches. I can tell you we had the most exciting time of our lives, for shells were dropping thick and fast around us, though almost miraculous to relate, the sole result was one casualty in the company. To add to the "enjoyment" of the bombardment it rained in torrents the whole night, and throughout the following day (Christmas Eve).

The welcome order came to stand to at about 10am, and we knew our relief was due - we should be in billets for Christmas Eve. Alas! Owing to the terrible state of the trenches the company detailed to relieve us took nearly four hours to get to the firing line through thick mud - in some places three feet deep. We knew our fate by the appearance of the newcomers, who were literally covered from head to foot in Flanders mud. At last came the order to retire, but it was easier said than done, and it was only after three and a half hours' struggle that we emerged from the communications trench on to terra firma. We arrived in billets at seven o'clock in the evening thoroughly done in, but very glad to spend Christmas Day in comparative peace and enjoying the contents of the welcome parcels from thoughtful friends at home.

So many days at rest in the trenches; so many at rest in the billets. This is the programme with little variation, but plenty of excitement, and of course at the price of danger, but the infectious chumminess of each and every man compensates for the necessary discomforts and hardships of trench warfare ... We spend our time out of the trenches in fairly comfortable barns, with straw for beds and the luxury of a fire and blankets. We are now back some fifteen miles behind the firing line for some days rest, and sports of various kinds are indulged in, in the village schoolroom, all of which tend to recuperate the men who have had a fair share of the shot and shell of the trenches.

On 21st February 1916, the Germans attacked the French at Verdun. To relieve pressure on the French, British units took over during March a thirty-kilometre stretch of the front between Loos-en-Gohelle to Ransart, south of Arras. The 24th Royal Fusiliers took over trenches from the French on 27th February 1916. Their War Diary records: "trenches good with deep dug outs front and support lines on high ground, the communications trenches very long; owing to thaw trenches beginning to fall in". However, the following day the Diary recorded:

A general settling into the new trenches taken over ... Considerable difficulty found in bringing up stores along the long communication trenches ... Parapets thin and loopholed and in nearly every case the thickness above the loopholes is about 1 sandbag so not bullet-proof.

The French approach was to fire through the loopholes, but the British practice was to fire over the top, so much work was done to close the loopholes and build up the parapets. Bringing up what was needed along communications trenches nearly two miles long was exhausting, especially in the wet and muddy conditions - there was particular concern about whether the older men (those over 40) could sustain the pace. Further, as the Diary observed on 10th March:

We worked hard at repairs to trenches and improving sanitary arrangements, the French having in our opinion rather peculiar ideas on this important matter so a great deal of work has had to be done.

In the conditions, much attention was paid to care of the men's feet, and the author of the War Diary was gratified to find that the Battalion had the lowest numbers in the Division of men suffering from trench foot. Casualties from enemy fire were also fairly low at this point.

However, on 21st May 1916 the Germans launched a substantial offensive from Vimy Ridge. The 24th Royal Fusiliers were at this time out of the line, though under orders to move up at two hours notice. The British front line was taken and a counter-attack failed (at considerable cost); after this, it was decided that the resources that would be required to regain the former position would be better deployed on the Somme. When the Battalion went forward again:

... every available man [was put] on the consolidation of the new front line and support line and wiring of the same. Work [was] ... only possible under cover of darkness.

They remained in this sector of the front until July. On 3rd July, while they were on trench duty:

At 10.45pm the Twins Crater s. of Momber Crater in the right front of the line held by the Battn, was blown. The Western edge of the crater was immediately occupied by 12 bombers of C Coy ... a consolidating party of 2 NCOs and 30 men of C and D Coys ... followed closely ... and continued until daybreak. An attack by 12 German bombers on the s. of the crater was driven off.

Things were not improved by bombardment from both German and British artillery of the position; the next two days were spent repairing the line from the effects of the crater explosion, the artillery bombardment, and incessant rain.

Their final stint in this sector was the following week, from 9th - 13th July. They then began the process of their transfer to the Somme front, arriving in Corbie on 20th July 1916.

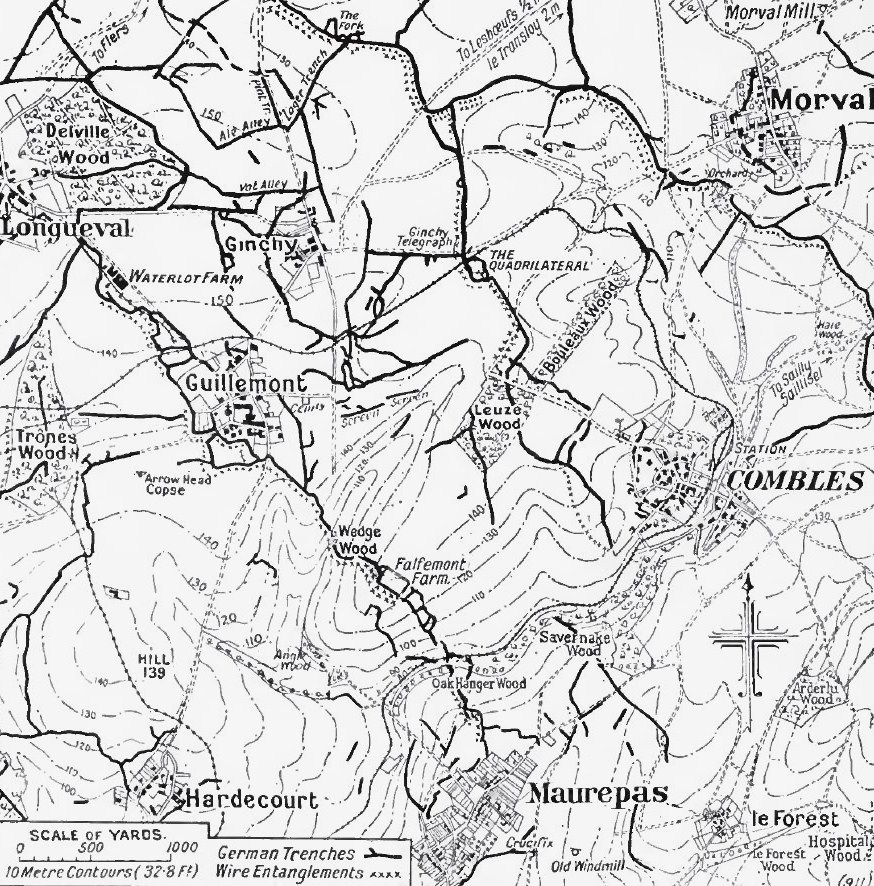

Delville Wood

On 25th July 1916 they relieved the 8th Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment at Bernafay Wood. By then, the British front line had moved forward from the positions held on 1st July, in the southern sector of the Somme front; Bernafay Wood, north-east of Montauban, had been taken by 8th July. On the way up to Bernafay, the 24th Royal Fusiliers were shelled, suffering two killed and seven wounded, and the shelling continued over the next two days. On 28th July, they moved further forward towards the front line, reaching the British position in Trones Wood; and finally on 29th July they were in the front line itself, occupying a position from the southern edge of Delville Wood to Waterlot Farm. Once again they incurred "several" casulaties from shell fire as they moved into position.

Delville Wood had been taken two days earlier, calling for "every available man" of the 22nd Battalion Royal Fusiliers - see the story of Robert Prowse Hearn - and had been temporarily cleared. 24th Battalion now had the job of taking the attack forward, just south of the wood.

According to the Battalion War Diary for 30th July 1916:

At 4.52am C Coy attacked the German trench 600 yds east of Waterlot Farm. The attack was unsuccessful owing to the wire not having been cut and difficulty of maintaining direction owing to thick mist. Of the 3 Officers and 114 other ranks who made the attack, [only] one officer [who was] wounded [and] eleven other ranks got back.

The Company Commander, Captain Meares, was one of those killed. The Battalion was relieved at 3.15am the following morning, going back into reserve trenches, and sustained further casualties while doing so. On 1st August, the Battalion was organised into two companies, such was the impact of the casualties of the last few days. They remained in the reserve trenches until 10th August, by which time they had reorganised back into four companies.

The War Diary includes lists of casualties for the month of July 1916. Other ranks killed during July totalled 57, 50 of whom died between 28th - 31st July. Other ranks wounded totalled 192, 39 of whom (and one officer) were wounded before the move to the Somme; 153 were wounded between 28th - 31st July (together with eight officers).

In addition, 101 other ranks are listed as missing as at 31st July. One of these names is William's. It seems that he was later reported "wounded", for his name appeared in casualty lists in this category, published in the UK on 13th September 1916.

How badly he was wounded, or when he returned to the Battalion, is not known, but it would seem that he did indeed do so, because he appears in the casualty lists in the War Diary a second time, after the Battalion was in action on 13th November.

The Battalion had returned to the trenches on 23rd August in the northern part of the Somme sector, near Beaumont Hamel. Here no progress had been made in pushing forward the British line, either on 1st July, or since. They spent two periods in the trenches during August and the first part of September, during both of which the situation was "quiet", according to the War Diary. In the second half of September and throughout October, they moved a little to the south, to hold the line opposite Redan Ridge.

The Battle of the Ancre

The fourth and final phase of the Battle of the Somme took place in November, with the aim of securing the best possible positions for the winter. It was decided that an attack would be made on either side of the river Ancre, as soon as the weather was sufficiently dry to provide reasonable ground conditions. The hope was that German resistance - which had proved so strong over the previous four months - would, or could, not be sustained much longer; that the artillery tactics so painfully learned by the British since 1st July would now bring about success; and that new mines and saps would considerably reduce the width of No Mans Land enabling the attackers to benefit from the advantage of surprise.

The 5th Brigade were on the right of the 2nd Division, opposite the Redan Ridge, with the 24th Battalion on the left of the Brigade front. The Regimental History describes the attack:

At 5.15am the attacking companies left the trenches in dense fog, reformed in No Mans Land, and moved forward with the general advance at 5.45am. The barrage was followed closely, the men being within 20 yards of it over the whole battalion front. Some shells, indeed, fell short and caused casualties, but the men followed coolly at walking pace into the German front-line trenches, and a numerous dug-out population emerged to surrender. The troops went on, and at 6.15am had taken the major part of their objective - the Green line - the German third line system.

They were able to consolidate this position sufficiently to hand it over the following day to the relieving battalion, the 2nd Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry; and thus contributed to the partial success of the attack on 13th November. However, the success had not been achieved without considerable losses. The War Diary listed:

3 officers killed in action on 13th November, one wounded, since died

9 officers wounded (three still at duty) on that date

22 OR killed in action on 13th November, 6 died of wounds subsequently

165 wounded on 13th November (eleven still at duty)

50 missing, as from the date of the attack.

For a second time, William was listed as "missing".

Death

On 29th December 1916, the Dartmouth Chronicle reported that “Mrs Bell, Sunny Bank, Ford Valley, has received news from the War Office that her husband, Pte W J Bell, Royal Fusiliers, has been missing since 13th November.”

On 10th January 1917, his name was amongst those reported in casualty lists as “wounded and missing”; and on 30th March 1917, the Dartmouth Chronicle carried a report providing some explanation for this status:

Private W J Bell Royal Fusiliers has been missing since the 13th November last. In the advance at Beaumont Hamel, he was seen in a shell hole very severely wounded, he was bandaged up waiting for the stretcher-bearers to take him away, as he had been there for many hours, but it appears that he was never found, for no news of him has been heard since.

It appears that it was not until the battlefields of the Ancre were cleared in 1917 that it was eventually confirmed that William had died. He was buried in Redan Ridge Cemetery No 3, near Beaumont Hamel, a cemetery made in the German front line trenches in which the battle had taken place.

William's parents placed an announcement of his death in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 17th August 1917:

Bell: Killed in Action in the advance at Beaumont Hamel, on the 13th November, 1916, Pte W J Bell, aged 30 years, eldest son of Mr and Mrs J Bell, Waterhead, Kingswear.

William had died almost exactly a year after landing in France.

Commemoration

William's grave in the Redan Ridge Cemetery was one of thirteen later destroyed by shell fire. His grave is now represented by a special memorial.

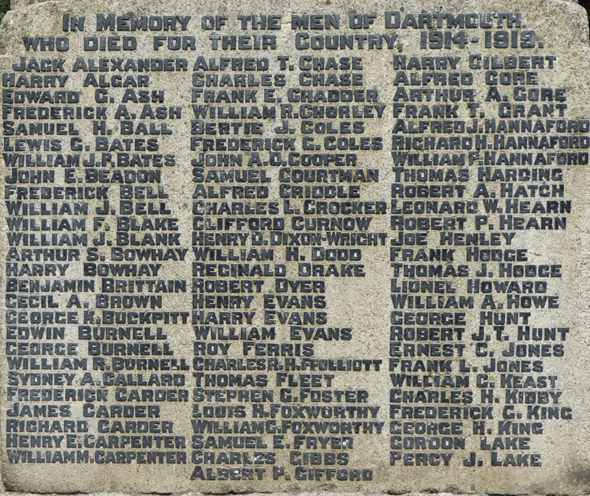

In Devon, he is commemorated both in Dartmouth, on the Town War Memorial, and in Kingswear, on the war memorial in St Thomas of Canterbury.

William's brother Cyril survived the war, being demobilised from the Royal Fusiliers on 16th May 1919.

His brother Frederick Gilbert also survived the war, leaving the Royal Navy as an Able Seaman on 3rd September 1920, having completed his twelve year engagement.

Sources

Kingswear's Heroes in Peace and War, by Tessa Gibson and Trevor Miles, publ Kingswear Historians

Dartmouth and Kingswear Steam Laundry, Reg Little, Kingswear Historian

The Chronicles of Dartmouth, a historical yearly log, by Don Collinson, publ 2009, Richard Webb

Naval Service records available for download from The National Archives, fee payable:

- William John Bell, reference ADM 188/548/360630

- Frederick Gilbert Bell, reference ADM 188/424/238972

War Diary of 24th Battalion Royal Fusiliers 1st November 1915 - 31st March 1919, available for download from The National Archives, fee payable, reference WO 95/1349

Army Service Numbers: The Royal Fusiliers - Sportsman's Battalions

The Sportsman's Gazette: a record of the Sportsman's Battalions

The Royal Fusiliers in the Great War, by Herbert Charles O'Neill, publ 1922, Heinemann (available online)

The Long Long Trail: Actions in the Spring of 1916 (Western Front)

The Somme, by Peter Hart, publ Cassell, 2005

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Bell |

| Forenames: | William John |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | SP/3130 |

| Military Unit: | 24th Bn Royal Fusiliers |

| Date of Death: | 13 Nov 1916 |

| Age at Death: | 30 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of the Ancre |

| Place of Death: | |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated at Redan Ridge Cemetery, near Beaumont-Hamel, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |