Harold Montague Mandley

Family

Harold ("Harry") Montague Mandley was born in Ilfracombe in 1890. He was the eldest son of John Mandley and his wife Frances Hexter. His parents lived at 12 Wonford Road, Exeter, where his father ran a grocery business, and he was baptised at St Leonard's, Exeter, on 25th September 1890.

John Mandley came from Clyst St Lawrence, where his father Henry farmed 74 acres. His elder brother Thomas followed their father into farming, but John decided on a different career. He obtained work as an assistant in the business of John Lethbridge, a wholesale and retail Grocer in Fore Street, Exeter. There he met Frances Hexter, the eldest daughter of William Hexter, who ran the "Star Stores Inn" in Fore Street (later The Mint Tavern). They married on 30th October 1889 at St Olave's, Exeter. We know a little more of their subsequent history than might usually be the case, from newspaper reports of an "interpleader case" brought by Frances at the County Court at Totnes in March 1897.

Frances' mother, Ellen Hexter, née Battershill, had died two years earlier, leaving her eldest daughter the fairly substantial sum of £1000, interest on which was paid to her until she came into the whole sum when she reached the age of 21, soon after her marriage. With her inheritance, John set up in business in Exeter as a grocer; Frances took the house at 12 Wonford Road, Exeter, buying furniture and other items necessary to set up a family home there. She also received several generous wedding presents from her family.

John, Frances and Harry were recorded living at 12 Wonford Road in the 1891 Census, and a daughter, Ethel Gwendoline, was born in 1893. Unfortunately, John Mandley's grocery business was not a success. He went bankrupt, and the money that Frances had put into the business was lost. With some difficulty, she managed to hold on to the family's furniture and other items of value, on the grounds that they were hers and not her husband's and so could not be taken in settlement of his debts.

The family then moved to Torquay, where John and Frances' third child, William Reginald, was born in 1895. John Mandley opened another grocery business, but this too failed. Frances, clearly a resourceful woman, decided to draw on her experience as an innkeeper's daughter, and set up in business herself. With the benefit of a gift of £500 from an aunt, a Miss Cousins, in 1896, the family moved to Dartmouth, and Frances took the lease of the Lindsay Arms in Lower Street, paying £150 for the goodwill, and additional money for the stock and license. According to newspaper reports, she carried on the business, and paid for everything. Only the license was in her husband's name, at the wish of the Magistrates granting it.

Frances was able to demonstrate to the Court that nothing in the Lindsay Arms belonged to John Mandley, and so was able to recover from the executors of her husband's latest bankruptcy, various items which the court accepted were hers, including a number of items given to her as wedding presents. Costs were also awarded in her favour. Nonetheless, at the judgement summons in John Mandley's bankruptcy case later that year, he was ordered to pay back his creditors at £2 per month, on the basis of takings at the Lindsay Arms of between £9-10 per week.

Frances Mandley would appear to have moved out of the innkeeping business fairly soon, as she was reported as having transferred the license to Mr Cross, of Torquay, in 1898. Although two more children were born to Frances and John in Dartmouth, Frances Gertrude in 1897 and Frederick Charles in 1900, it seems that by the time of the 1901 Census the couple were living separately. Frances and the children were recorded living in Bayards Cove, Dartmouth, where her household also included two boarders. John Mandley lived on the other side of Dartmoor, in South Tawton, near Okehampton, with his elder brother Thomas, who was the farm bailiff for the Wood House estate. It appears that he had found work looking after the mentally ill, because his occupation was recorded as "mental attendant".

John's story came to a sad end in 1902. Several newspapers reported an inquest by the Bristol Deputy Coroner at Redland, on 3rd March 1902:

...on the body of John Mandley, aged 43, a nursing attendant, formerly of Portview House, Bears Cove, Dartmouth. The evidence showed that the deceased was seen at Kingswear Station on January 9th, when he was going to Bristol, being an attendant at Dr Fox's Asylum and elsewhere. He had shown no suicidal tendencies, and had no worries. Nothing was heard of him by his wife after January 11th, until last Saturday when his dead body was found in the river Avon, near Rownham Ferry, having apparently been in the water about a fortnight. On his clothes were found various references, and four pawntickets, issued on the 13th and 14th January, by Mr Graham, of Broadmead, Bristol. Dr Parker, the divisional police-surgeon, could not definitely assign the cause of death, and the jury had to return an open verdict of "Found dead in the river Avon". The references found on his body gave him the highest character.

("Dr Fox's Asylum" was a private lunatic asylum at Brislington House, Bristol, established by Edward Long Fox in 1806 for patients who were segregated by class as well as by behaviour and condition).

Despite these very difficult circumstances, Frances was still able to create some stability for her children. They remained at Port View House, Bayards Cove, and as they grew older were frequently reported in the columns of the Dartmouth Chronicle winning prizes in sports events (the boys) or contributing to plays and pantomimes (the girls). By the time of the 1911 Census, Harry, aged 20, had begun his working life as a carpenter, apprenticed to John Heydon, a carpenter and builder in Dartmouth. His younger brother (William) Reginald had been apprenticed as a copper-smith, at one of Dartmouth's two large engineering firms, Simpson Strickland & Co. No occupation was recorded for Ethel, 18; the two younger children, Frances and Frederick, were still at school. William Polglass and George Brown continued to board with the family.

Service

7thBattalion Devonshire Regiment (Cyclists)

Harry's Army service papers are amongst the few that have survived (though damaged), so we know that he joined the 7th Battalion Devonshire Regiment (Cyclists) on 1st March 1910, reporting regularly every year for training. He signed on for four years, and on 28th August 1913, extended his service for a further year, to March 1915.

The 7th Battalion had been created as part of the Territorial Force in 1908 - the 5th Volunteer Battalion had a cyclist company based at Torquay, and this was used as the nucleus of Cyclist Battalion. By 1914 there were several cyclist companies; "F" Company was based at Dartmouth, very much a part of the local scene. Harry's younger brother Reginald was also a member, in May 1914 representing the "Dartmouth Territorials" in a shooting match with the Royal Naval College "under Bisley conditions - 200 and 300 yards, one sighting shot, seven rounds each distance. The Territorials won by one point.

At the outbreak of war, 7th Battalion had just finished its annual training at Churston Race Course, Paignton, and on 3rd August was at Battalion and Company headquarters. Harry was mobilised on 5th August 1914. Before the war, he had volunteered for the Special Service Section, responsible for South West Coast Defences, and so his first duty was to carry out coastal patrols. Detachments of the Battalion were sent all along the coast from Lands End to Lyme Regis.

Very soon, however, it was decided that the north-east coast was a higher priority. The following week the 7th Battalion, including both Harry and his brother Reginald, was sent by train to the north-east, responsible for coastal defence from Scarborough in Yorkshire, to Seaton Delaval in Northumberland, based at Whitby.

As part of the Territorial Force, which had been created for the purpose of home defence, members of 7th Devons had no liability to serve overseas. Most territorials, however, soon undertook to serve abroad, and Harry was no exception - he signed the form accepting this liability on 26th September 1914. (See also the story of Frederick Coles, a fellow member of the Battalion from Dartmouth, who had joined on 7th August 1914, who similarly accepted this liability on the same day). In the meantime, Harry's time in the north-east was not uneventful. On 30th October 1914, the Battalion was involved in helping to save the passengers and crew of the Hospital Ship Rohilla, wrecked off Whitby. During his time in Whitby, Harry also met a young lady, a "Miss Harland". At some point during his service in the north-east (or possibly when he later came home on a short leave), they became engaged to be married.

Army Cyclist Corps: 7th Divisional Cyclist Company

Harry did not stay long enough with the 7th Devons, however, to be involved their role assisting the civil powers when, on 16th December, the Germans shelled the north-east coast, including Whitby, causing many casualties. On 7th November 1914, the Army Cyclist Corps had been set up to bring together all the Regular Army cyclist companies attached to each infantry division (including the new army divisions raised under Kitchener). This did not affect the Territorial cyclist units, or the men in them, which remained as they were. However, it seems to have provided an opportunity for Harry, for he was discharged from the 7th Battalion on 13th December 1914, and reattested the following day in the Army Cyclist Corps at Southampton, being allocated a new service number, 564. Perhaps the attraction was the pay - this was the same as for the infantry, but "proficiency pay" was given to men who qualified as a proficient cyclist, and who had the necessary physical endurance. Harry was granted "Proficiency Pay class I" when in the field, as from 19th December 1914; and class II, with effect from 1st July 1915. Alternatively, perhaps it was the opportunity to get overseas more quickly.

On Christmas Eve 1914, he left Southampton for France, arriving at Le Havre on Christmas Day. He was posted to the 7th Divisional Cyclist Company "in the field" on 29th December 1914. The primary roles of cyclists were reconnaissance and communications, but as mobile infantry, could provide mobile firepower if required. However, the nature of trench warfare meant that much of their time in practice was spent on manual labour. According to Charles Messenger:

The original [cyclist] companies had performed well during the opening weeks of the war, but once the fighting became static there was little scope for their reconnaissance role. During First Ypres they helped to hold the line, but after the fighting died down, divisions began to see them as a source of manpower for the many humdrum tasks which needed to be carried out. Thus, the cyclists found themselves being used for patrols in the divisional rear areas, both to assist the military police and checking for spies. They were employed on digging and repairing trenches and burying signal cables.

During First Ypres, 7th Division had suffered very heavy losses, and so had to be substantially reinforced and rebuilt during January and February of 1915.

The War Diary of the 7th Divisional Cyclist Company is fragmentary, but it does record the arrival of one officer, Lt W Hill, and 56 men "from Army Cyclist Corps" on 29th December 1914. Harry's start with his new unit was not entirely happy - his records show that he fell foul of army discipline in February 1915, when he received 7 days "field punishment No 2" (hard labour and loss of pay) for "quitting his post when on active service when a Police Sentry about 10.30pm without being properly relieved".

The War Diary records that, during 1915, the Company was at Neuve Chapelle in March, Aubers-Fromelles and Festubert in May, at Festubert and Givenchy in June, and at Loos in September. However, no detail whatever is provided on these operations, other than the following on 26th September, the second day of the Battle of Loos:

On the night of 26th September 1915, the Company proceeded to the front line trenches near Hulluch and removed from them four German fieldguns which were captured on 25th September 1915 by 7th Division. It also assisted in the removal of three more. On the night of 27th September 1915, a party located and attempted to remove another. The attempt failed owing to lack of material for bridging three lines of trenches over which it was necessary to pass. These guns are now in England.

The Company's activities for the first three months of 1916 are listed on one sheet of paper. On 6th February 1916, they arrived at Sailly-Laurette on the Somme, south of Albert. Here, they were employed on road-building. On 6th March 1916, they moved to Buire-sur-L'Ancre, west of Albert, where they were "employed with Signals". On 31st April 1916, they were moved back to the Somme river, at Vaux-sur-Somme, where they were once again employed on road-building. Harry had another run-in with army discipline, this time more serious, involving "insubordination to an NCO and volunteering for the Guard Room [sic]" for which he received 14 days "field punishment No 1" - hard labour, loss of pay, and possibly, depending upon the policy of the unit, shackling for up to two hours in three days out of four during the period of the punishment.

Army Cyclist Corps: XV Corps Cyclist Battalion

In May and June 1916, the Cyclists went through another organisational change. Divisional Cyclist Companies were removed from divisional command level, and concentrated into Cyclist Battalions, at Corps level. Thus, the Cyclist Companies of 7th, 21st and 39th Divisions were amalgamated to form XV Corps Cyclist Battalion - and so Harry's record shows that he was posted to XV Corps on 11th May 1916.

The War Diary for XV Corps Cyclist Battalion accordingly begins on 11th May 1916 at Heilly, on the Ancre, south-west of Albert:

The 7th, 21st and 39th Divisional Cyclist Companies assembled at Heilly to form the XV Corps Cyclist Battalion, 326 strong, under the command of Major A J Hay.

Five days later the Cyclist Battalion was formed into three Companies, A, B and C. There were 159 NCOs and men who were surplus to the required number, and they were sent off to various infantry battalions.

The XV Corps Cyclist Battalion's War Diary is a much fuller record than Harry's previous unit. It shows that the Battalion spent the next ten months in the Somme sector. As the day of the great offensive approached, they were trained with mounted troops, to be ready if the much hoped-for "breakout" occurred; on 1st July 1916 itself, they moved upriver to Ribemont "ready to move at a moment's notice". They "stood to" for five days, but mounted troops were not called for. Instead, they were called upon for a variety of tasks. On 2nd July, three parties of one NCO and eight men were "sent out in reliefs to assist in turning back stragglers from the battlefield". On 4th July, four officers and 88 other ranks were sent to Becordel to mend the road into Fricourt. On 6th July, small parties were sent off on various tasks - one group was sent with Corps Cavalry to search for stray enemy prisoners, where the advance had been successful in overcoming German defences; another group was detailed off to assist a Royal Engineers Special Company (ie one dealing with gas or flame throwers); and a third group was required to report to 38th Division to hold Marlborough Wood in advance of infantry, against surprise attack.

On 13th July, with a new attack in the offing, they were brought up to the Citadel camp, near Fricourt, at midnight, "ready to move forward at shortest notice". But once again, they were not required, and after two days, returned to Ribemont. Much of the latter part of July and the early part of August was spent with the Royal Engineers, burying signals cables. In September they were back at Heilly, engaged on a variety of tasks. The Battalion War Diary mentions that one party of 50 men worked with the Ordnance Officer at the Meaulte railhead; a small party of two NCOs and ten men guarded a working party of 200 prisoners.

On 7th September, they were again brought a little further forward, to Becordel, where they were held in readiness for several weeks, presumably in case of the hoped-for breakthrough - which once again did not materialise. After several weeks, the Australian Cyclist Corps arrived on 26th October to relieve them.

As the final days of the Battle of the Somme continued into November, they were at a camp near Amiens called Le Catelet, with detachments at Poulainville, Talmas, and Flesselles, though there is no details given in the War Diary about their activities. Those not on detachment were undergoing training to keep up essential military skills, which might otherwise disappear amidst all the road building and trench digging - and the bicycles had to be maintained and kept clean, in case they were required. On 11th December, they were back on the Somme river, near Albert, at Sailly-le-Sec, where they spent Christmas Day; and during January, February, until mid-March, at Etinehem, nearby.

On 25th January, Harry went on leave to England for ten days - the first time he had been home since arriving in France over two years earlier. It seems that his priority on that visit was Miss Harland, in Whitby (see the newspaper report below) - whether he might also have found time for a visit to Dartmouth, is not clear. While he was away, and for several days after he returned, the Cyclists, working for the Royal Engineers, were burying water pipes to prevent them from freezing, in one of the coldest winters for several years. Late February and early March involved work on the construction of a "prisoners cage" near the village of Suzanne, upriver on the Somme, and on Hangers for No. 14 Wing Royal Flying Corps.

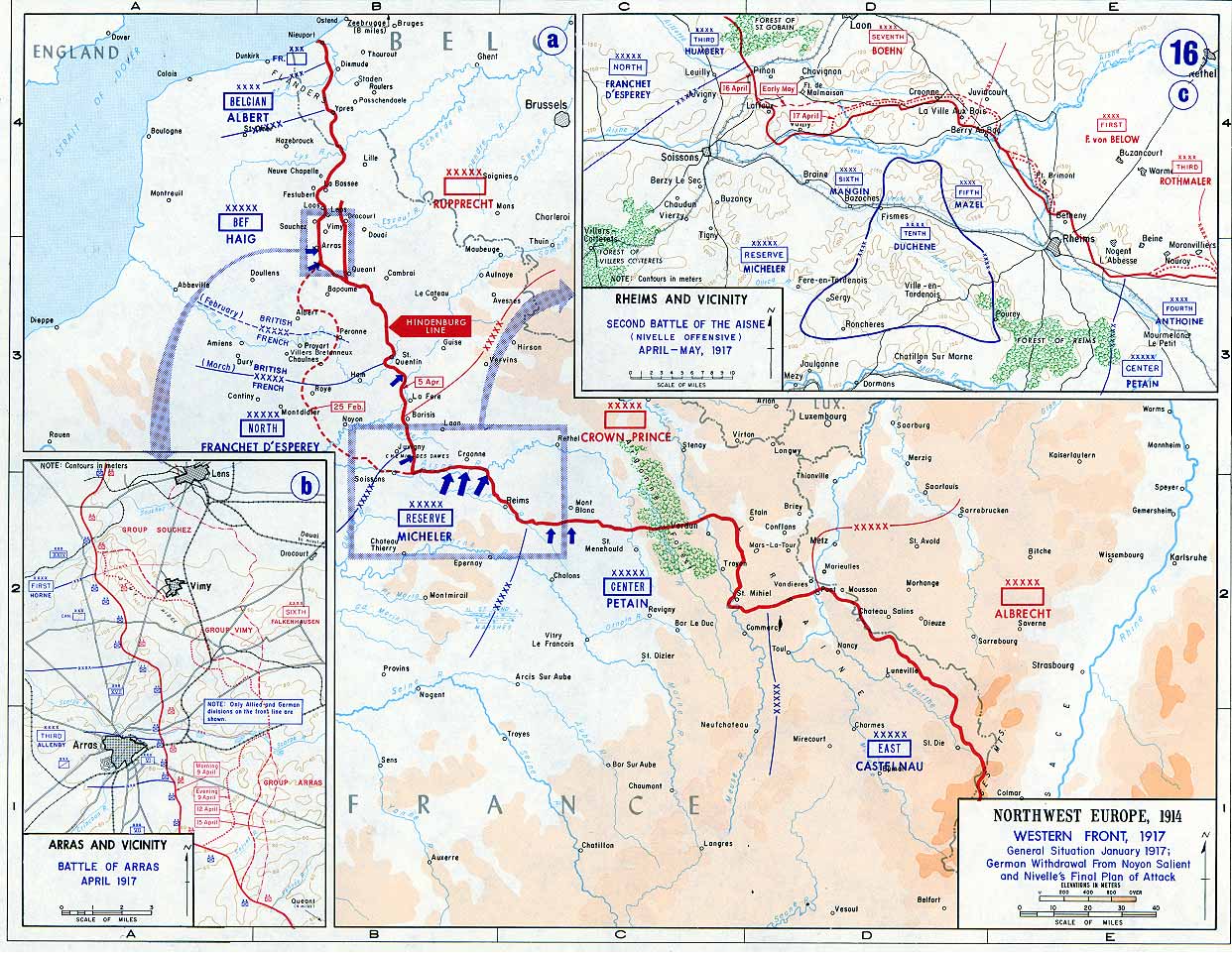

At some point, Lewis Guns had been issued to each company, and the sections responsible were instructed in their use, and carried out firing practice whenever possible. On 19th March 1917, the Battalion moved from Etinehem to Clery-sur-Somme, near Peronne; and suddenly, the tempo and nature of their activities changed. Though the Battalion War Diary does not say so, this was due to the overall military situation - the Germans had withdrawn on 16th March to a new defensive position on the Hindenburg Line.

The front-line had consequently moved more during those three days than over many months and there was much uncertainty about the new situation. Suddenly the Cyclists recovered their primary military purpose. One company was attached to 8th Division and another to 40th Division "for patrol duty and advance guard work". Moving cautiously forward through the evacuated areas, the latter Company occupied the village of Tincourt, three miles east of Peronne. Tincourt had been under German occupation since the autumn of 1914 and had been far enough behind the line to be used by German forces for billeting. On 21st March, the Cyclists were, according to the Battalion War Diary, "the first troops to enter the village. The Lewis Guns were brought into action and did well". They occupied Tincourt; the War Diary does not mention it, but other sources show that, due to the "scorched earth" policy followed by the Germans as they withdrew, the village was badly damaged and the area was partly flooded. Two men were wounded as the village was taken, one of them the company sergeant major.

The Battalion headquarters and transport then moved forward to the village of Moislains, north of Peronne, while the companies attached to Divisions continued their patrol and reconnaissance work. On 26th March, the company attached to 8th Division 23rd Brigade took part in the attack on, and capture of, the village of Equancourt; on 30th March, "B" Company, attached to 8th Division 25th Brigade, took part in the attack on the neighbouring village of Fins, positioned:

... between the two attacking [infantry] battalions and kept up communication between them. It was held up outside Fins but managed to push forward again with the assistance of its Lewis guns to cross-roads 2000 yards NE of Fins. Lewis Guns did good work.

One prisoner was captured; one cyclist was wounded, but remained at duty.

As the cautious British advance proceeded, the companies attached to Divisions continued with patrols and reconnaissance. On 4th April, "B" Company, attached to 25th Brigade, took part in the infantry attack between Fins and the neighbouring village of Gouzeaucourt, and "did excellent work. All three Lewis Guns were brought into action". However, there were some casualties - one officer was wounded, but remained at duty; two men were wounded, one of whom died; two others were slightly wounded, remaining at duty.

At this point, the advance stopped - for just beyond Gouzeaucourt was the new German defensive line. The new British front line began to consolidate accordingly. Two Cyclist companies remained attached to Brigades and carried out patrol and reconnaissance work until 15th and 16th April, when they returned to the Battalion. On 19th April, one officer and 20 men were involved in preparing the Corps "Prisoner of War Cage"; for others, a Battalion programme of training began again in their camp at Moislains.

Death

On 25th April 1917, the Battalion War Diary records:

Battalion Training. 18 other ranks return from Corps HQrs. One officer and 13 other ranks return from Prisoners Cage. Pte Mandley accidentally killed.

Because Harry's service papers include those from the Court of Enquiry held the day after he was killed, at the Battalion Headquarters in Moislains, we know in some detail what happened.

The Court was chaired by Captain R McDougill of XX Corps Cyclist Battalion, with two other officers from Harry's Battalion. Where possible the evidence is quoted in full - one statement is missing its final sentence, due to the condition of Harry's file. The culprit was one of the Lewis Guns that had done such "excellent work" during the previous few weeks.

Number 670 Lance Corporal RG Pridham was the witness to the death itself. He stated:

On the 25th April 1917 I was in charge of the Regimental Guard and about 3.30pm I was standing up in the Guard tent talking to the deceased who was also standing. I then heard the report of a gun and the deceased fell to the ground. I asked the deceased where he was hit but he was unable to reply. I then reported to the Regimental Sergeant Major that Pte Mandley had been shot. I examined the deceased and found that he had been hit through the back. It was obvious to me that death was instantaneous.

No 1312 Lance Corporal G Jones was running the Lewis Gun class in which the gun that killed Harry was fired. He stated:

On the 25th April 1917 I was instructing a class of one NCO and four men in Lewis Gun work between the hours of 3pm and 4pm. I was to instruct the Class in stoppages and immediate action. I obtained five dummy cartridges from the Armourer Sergeant (in addition to one given to me in the morning by Lt Hill, my Coy Lewis Gun Officer) which consisted of .303 SAA with the explosives taken out. Before commencing, I strictly warned the class not put any live rounds on the table. Pte Pattison was the second man to operate the gun. I placed the dummies in the magazine at an interval of one and two spaces and told Pte Pattison to carry on with the immediate action. The first time that he pressed the trigger a dummy cartridge was ejected in the proper manner. After reloading the second time he pressed the trigger, there was a report of an explosion. The bullet passed through the instruction hut, I immediately went outside and was then informed that a man had been hit in the guard tent. The only possible way that I can account for a live round getting amongst the dummy rounds is that a live round was picked up from the floor when the dummies were collected after ejection in the first stoppage.

No 6221 Private Pattison fired the shot that killed Harry. He said:

On the 25th April 1917 L/Cpl Jones was giving instructions in stoppages of the Lewis Gun. I saw the dummy cartriges put in the magazine for Pte [Nichol] and they all passed through the gun correctly. L/Cpl Jones then reloaded the magazine, I did not see this done as I received instructions to turn my back on the gun. When the magazine was put on the gun, I carried on with the stoppages. The first time I pressed the trigger the cartridge was all right but on pressing the trigger the second time an explosion took place. L/Cpl Jones warned us to be very careful not to put live cartridges anywhere near the dummies. I can offer no explanation as to how a live round got amongst the dummies.

No 10618 Pte H R Nichol was the first member of the class to fire the gun. He said:

On the 25th April 1917 I was receiving instruction in stoppages of the Lewis Gun under Cpl Jones. Before commencing Cpl Jones made sure that there were no live rounds on the table. I worked out the stoppages and nothing unusual happened. Cpl Jones then reloaded the magazine after collecting the dummies, some of which had fallen on the floor. Pte Pattison then took over the gun, the first time he pressed the trigger everything was correct but either the second or third time he pressed the trigger an explosion occurred.

No 9901 Pte C W Palmer, No 7162 Acting Cpl E Skelton and 6758 Pte R Collier were the other members of the class and gave evidence "as given by the 4th witness" (ie Pte Nichol).

L/Cpl Jones was then recalled and gave additional evidence. He said:

The five dummy cartridges used consisted of an ordinary .303 SAA with explosives taken out and the cap exploded and with two small holes drilled in the cases. The one handed to me by Lt Hill consisted of a .303 SAA with the explosive out and the cap removed. The case of the cartridge is of a lighter shade than the Regulations ... [last line illegible due to loss of bottom of page]

The Court accepted what they had been told and decided that the death was an accident and no-one was to blame. Their verdict was:

The deceased met his death accidentally from a bullet fired from a Lewis Gun during a class of instruction. The NCO in charge of the Class took all necessary precautions and Pte Pattison who fired the shot is exonerated from all blame. We consider it possible that a stray round of live ammunition could be picked up from the floor among the dummies and placed in the magazine.

However, when on 30th April 1917 Lt Col Thynne, the CO of XV Corps Mounted Troops, sent the Court of Enquiry papers up the chain of command in XV Corps, he did not take the same view:

Reference enclosed, I cannot concur in the finding of the Board.

- I do not consider the NCO in charge of the class, nor the officer supervising Lewis gun instruction, free from blame in view of last paragraph A.R.O. 321 dated 9.12.16, in spite of that having since been cancelled.

- With ordinary precautions it should not have been possible to pick up a live round on the floor of a hut used for Lewis Gun instruction.

- I think it a mistake to have used two patterns of dummy cartridges at the same time, also there is no doubt that the patterns used were not authorised by G.R.O. 2065, A.R.O. 669, and A.R.O. 841, but there appears to have been difficulty in obtaining the correct patterns, and so it was found necessary to use improvised ones made by Cyclist Armourer Sergeant. I think if more holes had been bored in these latter dummies an accident would have been less probable.

Brigadier Frith, Corps Deputy Assistant Adjutant and Quarter Master General, agreed, replying to Lt Col Thynne on 1st May 1917:

With reference to attached Court of Enquiry:

It is considered that there is no evidence [sufficient?] to warrant trying anyone by Court Martial for negligence [in] causing the death of Pte MANDLEY. There is no doubt, however, that there was great slackness in the manner in which Lewis Gun instruction was carried out. If proper supervision by the Lewis Gun Officer, Lt Hill, and L/Cpl Jones had been exercised, there should have been no possibility of a live round getting mixed in with the practice rounds, nor should the gun have been pointing in the direction where it could do damage.

Lt Hill should be severely censured for not having exercised closer supervision of the Lewis Gun practice. It is for your consideration whether L/Cpl Jones should not be reverted to the permanent rank of Private.

A brief note is included within Harry's papers stating that: "Disciplinary action has been carried out". Another note states, however, that L/Cpl Jones was not put on a formal disciplinary charge because he had been exonerated by the Court of Enquiry. But he had been "admonished" by Lt Col Thynne, who "lectured" him - he was told to keep stricter watch on classes in future. No reference is made in Harry's papers to any action taken in relation to Lt Hill. Ironically, it was Lt Hill who had accompanied the draft of Cyclists to France, including Harry, to join 7th Divisional Cyclist Company on 29th December 1914.

Subsequently there was a flurry of correspondence at XV Corps over why improvised dummy cartridges had been used when "there has always been an ample supply of the dummy cartridges with metal bullets and holes drilled in the case, provided for by A.R.O. 669"; fairly swift action was taken to obtain sufficient supplies of the new dummy bullets meeting the particular regulations mentioned in Brigadier Frith's comments.

News of what had happened reached Dartmouth quickly. An announcement of Harry's death, though with no reference to the circumstances, appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle on 11th May 1917:

Mandley: April 25th 1917, killed in France, Harold Montague Mandley, Army Cyclist Corps, aged 26, eldest son of Mrs F Mandley, Port View, Dartmouth

This preceded the formal publication of Harry's death in the casualty list, which was printed in the Western Times of 22nd May 1917. This did identify the death as accidental:

Latest Casualties in West-Country Regiments

Accidentally Killed: Army Cyclist Corp - H Mandley (Dartmouth)

Extensive coverage appeared in the Whitby Gazette on 25th May 1917, presumably thanks to Harry's fiancee Miss Harland. It appears that letters of condolence were sent to her from Lance Corporal Pridham, who had been with Harry at the moment he was shot; and apparently, from Lt Hill also. The Whitby Gazette was much interested because of the time spent in the town by the 7th Devons in the early months of the war:

Letters have been received from the Western Front bearing the sad tidings that Cyclist Harry Montague Mandley, Devonshire Cyclist Corps, had been accidentally shot. He was in Whitby at the time of the wreck of the hospital ship Rohilla, and rendered much assistance in the work of rescue. In November 1914, he volunteered for active service and was drafted abroad on the following Christmas Eve, and, with the exception of ten days leave, which he spent in Whitby three months ago, has been abroad nearly two and a half years. He was twenty-six years of age and his home was at Dartmouth Devonshire, but at the time of the outbreak of war he was at Exeter, where he was following the occupation of joiner and cabinet-maker.

Writing to the deceased soldier's mother, on May 7th, Lance-Corporal R G Pridham, of the same Regiment, says:

"I am writing to you to offer my deepest sympathy in the great loss you have sustained through the death of your son. He and I were the greatest of friends, having come to France together and been together practically all the time. He was well liked by all who knew him in the Battalion, and his friends wish me to express for them their deepest sympathy towards you in your bereavement. That he died for his country, I know, is but small comfort for you, yet it is some little consolation, for no man can die more honorably".

Writing on May 14th to Miss Harland, 5 Marine Parade, Whitby, to whom Cyclist Mandley was engaged to be married, his Commanding Officer says:

"Please accept my sincere sympathy, because he was one of my best men and always did his duty, whatever it was, with the utmost energy and keenness. He was killed one afternoon by a bullet fired in mistake by a machine gun, which was being cleaned, about a hundred yards from where he was standing. He didn't suffer in any way as his death was absolutely instantaneous. I was on the spot about a minute after he was hit, so can vouch for that. It was a very unfortunate accident and nobody was more sorry than I was, having brought him out from England in 1914, and having had him in my Company ever since! He was buried with full Military honours. The whole Battalion attended the funeral, his coffin was covered with the Union Jack, and his grave is marked by a cross; with flowers around. I will probably come to tell you all about the accident and the exact location of his grave when next on leave."

Cyclist Mandley had served four years in the Territorials prior to the outbreak of war. His brother, Sergeant W R Mandley, who was also in Whitby at the time of the wreck of the Rohilla, and assisted in the work of rescuing the crew, has been transferred to the Royal Flying Corps as a 1st Class Mechanic, an injury he received to his shoulder at the time of the Rohilla wreck, and for which he was for a time a patient at the Whitby Cottage Hospital, having incapacitated him for active service.

Harry's papers, together with Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, show that he was buried in the German Hospital Cemetery at Moislains - which must have been the location for the ceremony described in Lt Hill's letter.

On 30th October 1917, Frances received Harry's personal belongings, from Army Cyclist Corps Records at Hounslow, all recorded in detail in Harry's papers:

- one pair leather gauntlets

- one metal cigarette case

- one brass matchbox case

- one purse containing one blank disc and three farthings

- one jack knife

- one gold ring

- one leather wallet

- two cardboard wallets

- one comrades writing wallet with envelopes and paper

- one pair scissors

- one wrist watch with broken metal strap and cover

- one sparking torch

- one set upper false teeth

- one piece broken badge

- one address book

- one Testament

- one note-holder

- one soldiers diary 1916

- one Soldiers Prayers

- Correspondence-cards

- Photos in linen bag

Commemoration

Harry is now buried in the extension to the Peronne Communal Cemetery. After the Armistice, graves were brought in from battlefields north and east of Peronne and from several small cemeteries in the area, including all those in Moislains. His service papers confirm that his body was exhumed from Moislains and reburied in Peronne.

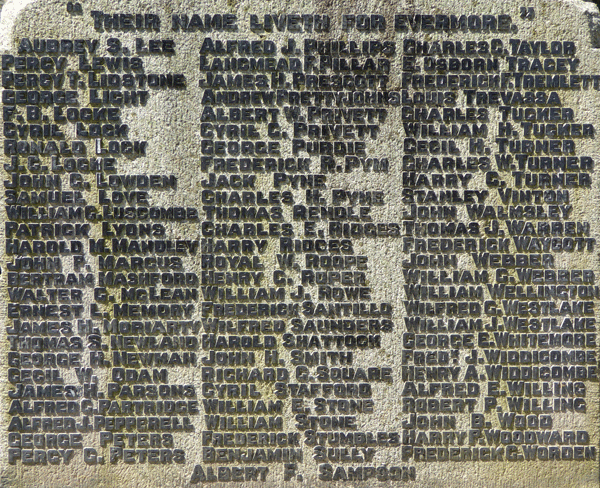

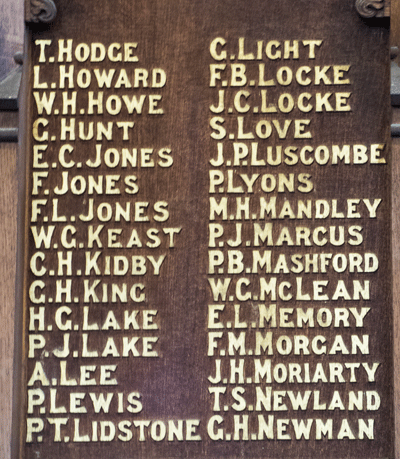

In Dartmouth, Harry is commemorated on the Town War Memorial and on the St Saviour's War Memorial Board (where the initial letters of his first and second name were inverted in error).

Sources

Army Service records for Harold Montague Mandley accessed through subscription websites, fee payable

War Diary for 7th Division Divisional Cyclist Company available at the National Archives, fee payable for download, reference WO 95/1642/2

War Diary for XV Corps Cyclist Battalion available at the National Archives, fee payable for download, reference WO 95/930/2

Call to Arms: The British Army 1914-1918, by Charles Messenger, publ Cassell, 2007

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Mandley |

| Forenames: | Harold Montague |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 564 |

| Military Unit: | XV Corps Cyclist Bn, Army Cyclist Corps |

| Date of Death: | 25 Apr 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 26 |

| Cause of Death: | Accidentally shot |

| Action Resulting in Death: | |

| Place of Death: | Near Moislains, France |

| Place of Burial: | Buried Peronne Cemetery, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |