Francis Richard Ferris Jarwood

Family

Francis Richard Ferris Jarwood was born in Dartmouth in 1893 and baptised on 9th April 1893 at St Saviour's. He was the second son of Richard Ferris Jarwood and his wife Fanny Adams.

Richard Ferris Jarwood was born in Dittisham in 1871 where his father was a farm labourer. By 1881 the family had moved to Townstal, Dartmouth, where they lived at Mount Boone Cottage. Richard became a blacksmith, and in 1891 married Fanny Adams, the daughter of Andrew Soper Adams, a fisherman, and his wife Sarah Ann Blamey. Fanny was born and brought up in Dartmouth.

Richard and Fanny's eldest son Andrew was born in 1892, followed by Francis in 1893. When Francis was only a few months old, Richard decided to practice his craft in the Royal Navy. He signed on for a twelve-year continuous service engagement as a Blacksmith on 5th September 1893. His first posting after his initial training took him to the other side of the world, to the Australia station in Sydney, where he served in HMS Katoomba and HMS Mildura, both in the auxiliary squadron, and did not return until 1st September 1897. His third child, Fanny, was born whilst he was in Australia.

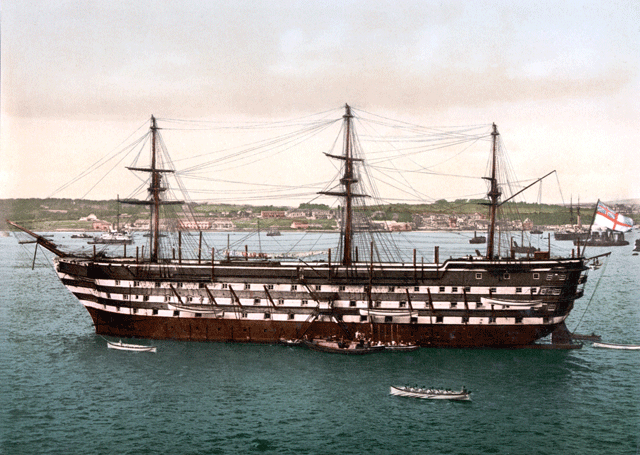

Whilest Richard was away, Fanny (senior) remained in Dartmouth, to be close to her family. But his next posting was to HMS Impregnable, the Navy's training ship for boy seamen, in Devonport, where he remained for the next three years, followed by eighteen months in the Devonport Naval Base.

So the family moved away from Dartmouth to Devonport, where all their remaining children were born. In 1901 the Census recorded the family at 20 Pembroke Street Devonport; by this time two more little girls had been added to the family, Gladys in 1899, and Laura in 1901, just before the Census. Richard remained in the Navy, signing on for a further ten years service in 1905, and the family remained in Devonport. Lilian was born in 1902, but sadly, died the following year; William followed in 1904; and Edward in 1906 - sadly he too died when only a few months old. Reginald was born in 1907 and Gertrude in 1910. By the time of the 1911 Census, when Richard was recorded serving as a Blacksmith in HMS Argyll, in Gibraltar, Fanny and the younger children had moved a bit further up the street, at number 90 Pembroke Street.

Both Francis, and his elder brother Andrew, had left home. Andrew, having worked in a canteen, joined the Navy on 5th January 1911, as an officer's steward 3rd class. On 8th August 1911 he joined the dreadnought battleship HMS Colossus as she was commissioned at Devonport, and served in her for several years.

Francis had moved north. The 1911 Census recorded him living with his aunt Bessie, in 5 York Road, Seacombe, Wallasey, across the river Mersey from Liverpool. Bessie Adams, his mother's elder sister, had married Henry Bawden, a widower, who was a joiner, in Liverpool in 1894. Bessie and Henry had a large family but Henry had died the year before the Census. Francis thus joined his aunt Bessie and his cousins Ernest, Sidney, Harry, Edith, Reginald, Redvers and Jeannie, as well as his uncle's sister Jane, also widowed, and a boarder, James Mason, in the house at York Road. At the time of the Census, Francis was working as a grocer's assistant.

Service

Unusually, Francis' army service papers have survived (though they are damaged and in some places, fragmentary or difficult to read). We therefore know that he enlisted directly into the Army Special Reserve on 19th September 1911, at Birkenhead, joining the Royal Welsh* Fusiliers as a private, number 4404. The Special Reserve was a form of part-time soldiering, similar to the Territorial Force. Men enlisted for six years, accepting the possibility of being called up in the event of a general mobilisation. Their service began with up to six months full-time training (paid the same as a regular) and there were three-four weeks training per year thereafter.

In Francis' case, he completed four months training on 18th January 1912, followed by another month of "recruits' musketry" between 17th May 1912 and 16th June 1912. He was then free to return to civilian life until next called up for training; and some Liverpool crew lists show that he worked as an Ordinary Seaman on the merchant ship Haverford, sailing from Liverpool, on three trips during the second part of 1912. His army record states that he completed his special reserve training in 1913 and 1914. During this period he continued to live at 5 York Road, Seacombe, despite the death of his aunt Bessie on 1st June 1913.

With the outbreak of war, the Special Reserves were mobilised immediately and Francis was one of 63,933 men called up to fight. According to his service records, he reported to the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion at Wrexham on 5th August 1914, the day after war was declared. At that time the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion was in Wales but by 8th August had returned there to deal with the large number of reservists who had reported for duty, so many that the barracks were unable to hold them and tents had to be put up on the football field.

The role of the 3rd Battalion was to provide trained reinforcement drafts for the active service battalions, but Francis was not yet called upon to go overseas - he was posted to the Regimental Depot at Wrexham, where he was shortly joined by the writer Robert Graves, who was awarded a permanent commission in the Special Reserve Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers a week after war was declared. Robert Graves included a description of this early period of his service in his memoir of the war, "Goodbye To All That". He mentions that men at the Depot frequently deserted for short periods, and indeed, on 4th October 1914, Francis went absent without leave for 3 days and 22 hours, earning himself a penalty of fifteen days confined to barracks. Soon afterwards, he was posted to the 1st Battalion on 1st November 1914, arriving in France the next day.

In Dartmouth, the Chronicle recorded three members of the Jarwood family amongst "Dartmouth men serving with HM Forces":

Francis Richard Jarwood, RW Fusiliers

1st Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers

The 1st Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers had been in Malta at the beginning of the war, and came home to England on 3rd September 1914 to form part of the 7th Division. They landed at Zeebrugge on 7th October 1914 to assist in the defence of Antwerp, and were then involved in the First Battle of Ypres, suffering heavy casualties. The War Diary of the Battalion is in a rather damaged state at this point, but it reports much needed reinforcements arriving on 5th, 9th, 11th, and 12th November - possibly Francis was one of these. On 13th November, the Battalion having come out of the trenches to billets at Merris (just to the west of Bailleul), "the details 1RWF and drafts were reorganised into four companies ... while resting at Merris". They were back in the trenches again on 14th November, with more reinforcements arriving on 22nd November and 4th December. The Battalion remained in the trenches until that date without relief, though "companies were relieved for three days at a time and were billeted in rear of the trenches". Over the next few months they remained on nearly continuous trench duty.

Between 10th-12th March 1915 the Battalion participated in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. As part of the 7th Division, they were in reserve but nonethess sustained several casualties (for an account of the battle, see the story of James Maddick Moses Tuckerman). They went into billets at Fort d'Esquin on 17th March 1915, returning to the trenches near Laventie on 11th April for two days. During this period, the MP William G C Gladstone, the grandson of William Gladstone the Prime Minister, arrived to serve with the Battalion as a second lieutenant, and died of wounds only two days later, on 13th April, having been shot by a sniper (Robert Graves comments that he exposed himself unnecessarily). The 1st Battalion was relieved on 14th April and marched to billets in La Gorgue, Merris on 28th April, and back to La Gorgue on 6th May 1915. They were about to go into the attack at the Battle of Aubers Ridge, a British offensive undertaken in support of a French attack further to the south.

Aubers Ridge

The battle was a disaster for the British Army. The page of the Battalion's War Diary is quite badly damaged but the following can be read (or safely inferred):

During the night of the 8th-9th the [8th and 7th] Divisions took up their respective positions [in the] assembly trenches preparatory to the attack, the general idea being for the 8th Division [to] break the line and the 7th Division to [go] on through the gap, the RWF being [given] the task of taking Aubers Village and La Plouigh and La Cliqueterie farm[s]. Our artillery bombardment began at 5am the bombardment being less intense and prolonged than that of Neuve Chapelle.

At 5.40am the infantry of the 8th Division advanced to the attack and captured the 1st and 2nd German trenches but suffered heavily in the advance. The enemy brought a most intense fire to bear on the captured trenches and in consequence our infantry had to fall back to the British trenches. The RWF did not leave the assembly trenches. The want of success can only be attributed to the British artillery bombardment which failed to destroy the enemy's barbed wire entanglements and in other respects was a complete failure.

However, as the 1st Battalion RWF had not got anywhere near attacking, they suffered only 5 other ranks wounded. They were moved to Essars on 10th May, to be brought back into the attack at the follow-up Battle of Festubert.

Festubert

The bombardment opened on 13th May and units were brought into attacking positions on 15th May. The first wave of the attack went forward at 11.30pm, with some success on the right of the British front. On the left, heavier resistance was encountered. The 1st Bn RWF left Essars at 8.30pm, to be brought into the second wave of the attack, after a further bombardment.

At 2.45am the intense bombardment commenced and ceased at 3.16 am. The Battalion immediately assaulted - Each company in two lines and company behind company - order of companies A, B, C, D. The parapet was mounted by scaling laders - our wire had been previously cut and bridges thrown across a broad ditch which ran along our front ... The Battn suffered very heavily from shell and machine gun fire both in crossing the parapet and the space between our parapet and the 1st German line.

Several officers were killed but:

... the German front line was however quickly stormed ... the 2nd German line was also quickly carried and the line pushed on. A heavy MG & rifle fire then opened from the left front ... The rear half of the Bn suffered very heavily in getting to the German trench only 3 officers of the company reaching it unwounded ....

Command of the Battalion had passed to Captain Stockwell, who was able to pull together remnants of companies and organise a further advance toward the objective of La Quinque Rue, in the village:

... until forced to halt by the fire of our own guns from which they suffered severely. About 7am touch was obtained with a platoon of the Warwicks sent in support and the Northern end of the long German communication end which was the Battn objective was carried ... shortly afterward 2 coys of the Queens and two companies of the Warwicks worked up the trench and the trench was fully occupied. The N end of the trench ended in some houses and an orchard. One of the houses was cleared by the Battn and placed in a state of defence but the other houses and orchard were held by the Germans. The enemy made no effort to attack but sniped from front flank and rear.

About 2pm the enemy commenced shelling the trench with HE. The trench afforded little cover. Reinforcements were asked for to clear the orchard and houses ...

100 men of the 7th Londons were sent up for this purpose and the orchard was taken, but machine gun fire forced them to fall back.

... in the meantime about 600 yards of the trench occupied by other corps was heavily shelled and rendered untenable and the Bn found themselves separated from the rest of the Brigade.

At about 7.30pm the Battalion was ordered to fall back and was then withdrawn during the night.

The Battalion War Diary records the following very heavy casualties:

| Officers: | killed: | 6 |

| died of wounds: | 2 | |

| wounded: | 9 | |

| wounded and missing: | 1 | |

| missing: | 1 | |

| Total: | 19 |

| Other ranks: | killed: | 118 |

| wounded: | 271 | |

| wounded and missing: | 6 | |

| missing: | 164 | |

| Total: | 559 |

The strength of the Battalion going into the action had been 25 officers and 806 NCOs and men. Unusually, the Battalion's War Diary includes a copy of a private letter sent to his parents by Lt A K Richardson, who survived the battle:

My dear mother and father,

We have just had the most awful Battle and thank God I have come through unscathed ... the Artillery bombardment commenced at 2.15am ... Then came the time, the whole of our line with one leap were over our parapet, and on towards the German lines. It was a sad spectacle owing to fearful rifle and machine gun fire mowing our poor fellows over, not to speak of high explosive and shrapnel shells ... Stockwell with a handful of men were on the extreme left of line with no support - I at once packed off there, on arrival I found Stockwell with Warmsley who appeared to be the sole survivors of the Regt, holding a communication trench leading to an orchard and some ruined houses. The trench was like brown paper as far as being bullet proof went ... All day we remained holding our trench ... We were shelled throughout the day ... we were very short of ammunition. Stockwell sent for reinforcements and ammunition which never came ... This last show was the worst I have ever been in. We only have 400 men left in the Batt...

Perhaps Francis was one of those "mown over" in the initial advance, for his service records show that on 16th May 1915, he suffered a gunshot wound to his left leg. He must have been taken off the battlefield quickly, and the rest of the casualty evacuation chain operated swiftly and effectively - he was admitted that day to No 23 Field Ambulance, in Bethune, and transferred the following day to Rawalpindi British General Hospital at Wimereux. From there, on 18th May 1915, he was transferred to England, where he spent 31 days in hospital (his record does not state to which hospital he was sent). His wound recovered well and there was no fracture. He was discharged to "light duty" on 18th June 1915, and on 19th August 1915, he was posted once again to 3rd Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers, which by this time had moved to Litherland Army Camp, on Merseyside.

Marriage

On 1st September 1915, at Birkenhead, Francis married his first cousin, Edith Irene Woodman Bawden, a younger daughter of his aunt and uncle Bessie and Henry Bawden. Edith was by then aged 19; although both her parents were dead by this time, she still lived at 5 York Road, Seacombe, where Francis had lived before the war. Francis' army record states that he forfeited pay between 5-16th September 1915, and again between 26th September - 5th October, though it does not state the reason - perhaps he extended his honeymoon, for he was due to go back to the front.

On 11th October 1915, he embarked the SS Princess Victoria at Southampton, arriving in Rouen the following day. He reported to No 4 Infantry Base Depot in Rouen and then joined 2nd Bn Royal Welsh Fusiliers "in the field" on 15th October 1915.

2nd Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers

On 15th October 1915 the 2nd Battalion had been in billets at Annezin, near Bethune, for twelve days. This must have been welcome relief after their participation in the Battle of Loos, memorably described in "Goodbye to All That" by Robert Graves, who had joined the Battalion the previous July. Francis was one of a party of 100 other ranks arriving as much-needed reinforcements after the heavy casualties incurred after the battle - as Robert Graves says:

At Annezin we reorganised. Some of the lightly wounded rejoined for duty, and a big draft from the Third Battalion arrived, so that within a week we were nearly seven hundred strong, with a full supply of officers.

The following day the Battalion moved to billets in Bethune, and from there went into the trenches in Cambrin for a five-day spell of duty, which was reasonably quiet. During November they were first in the support line, supplying working parties "bricking and improving communication trenches", and then on 13th November, in the front line, until 19th November. The War Diary records that Robert Graves, who had been gazetted Captain in the Special Reserve the same day Francis arrived in the Battalion, transferred to the 1st Battalion RWF on 26th November. There Graves famously met, and became friends with, Siegfried Sassoon, who had arrived in France on 17th November 1915, joining the 1st Battalion RWF. Thus, although Francis and Sassoon were in the same battalion, they did not serve at the same time.

On 6th December, the 2nd Battalion RWF went into the line at Windy Corner, a cross-roads north-west of the village of Cuinchy, for five days, where, according to the Battalion's War Diary, things were "comparatively quiet". They enjoyed Christmas out of the line, returning to the trenches on 29th December at Cambrin, and remained in this sector for several months. There was mining, and counter-mining, and trench raiding, but the sector remained relatively quiet most of the time. On the other hand, as Robert Graves famously remarked:

Cuinchy bred rats. They came up from the canal, fed on the plentiful corpses, and multiplied exceedingly. While I stayed here with the Welsh [Regiment][earlier in 1915] a new officer joined the company and in token of welcome, was given a dug-out containing a spring-bed. When he turned in that night, he heard a scuffling, shone his torch on the bed, and found two rats on his blanket tussling for the possession of a severed hand. This story circulated as a great joke.

If this sort of experience was only half true, Francis must still have been more than pleased to have been given two weeks leave in England from 19th March 1916 to 26th March 1916, during a period in which the Battalion was out of the trenches.

His record also shows that on 1st May he was admitted to a Field Ambulance (unidentified). The Battalion War Diary records that on 1st May 1916, whilst the Battalion was in the trenches near Cuinchy, "four other ranks wounded, slightly, at duty". Francis returned to duty from the Field Ambulance two days later. He most probably was aware of his father and brother both taking part in the Battle of Jutland, on 31st May 1916.

In his own war, the previously quiet sector hotted up on 22nd June, according to the War Diary:

the enemy exploded a mine on the right of Givenchy Left, under B Company's front line, wrecking completely about 80 yards of the line and doing considerable damage to the support line. At the same time a very intense bombardment was put up by the enemy on the front line, support line and Battalion Headquarters, of all calibres up to 8". This lasted for 1½ hours, after which the enemy attacked with 150 men and entered our first trench, but were promptly evicted by the small remnant of "B"Company left after the mine explosion and bombardment.

Casualties were high - one officer was killed and three were missing; the company sergeant major was also missing, as were 45 men. 34 men were wounded and 8 men were known to have been been killed.

There were also casualties amongst a Royal Engineers tunnelling company who had been underground at the time and who were buried alive, one of whom, Sapper William Hackett, remained with an injured colleague, Thomas Collins, until they were both killed when the gallery collapsed again. The resultant crater, now known as the Red Dragon Mine Crater, was the largest crater on the Western Front at the time.

"B" Company (what was left of it) were promptly relieved by a company of the 1st Cameronians while the rest of the Battalion repaired the damage as quickly as possible. Then, enraged by the losses, "A" and "D" Companies carried out their own raid in retaliation on 5th July:

after a concerted bombardment of the salient by trench mortars, artillery and rifle grenades with an expenditure of 10,000 rounds in ¾ hour, "A" Company on the left and "D" Company on the right assaulted the enemy trenches with the intention of staying in them 2 hours, and in that time to completely wreck the enemy mining system, dug-outs, trench mortar emplacements etc. This was more than fulfilled ... 39 prisoners were captured, 4 dead brought in, 14 identity discs taken off others, and many others known to have been killed and wounded. In addition, 1 machine gun, 1 trench mortar, much equipment, food, correspondence, knicknacks and rifles were captured. The enemy third line was entered and destroyed by us".

A large minnenwerfer was also destroyed.

One officer and ten men were killed, one man was missing, and one officer and 47 men were wounded. Robert Graves, who had left the 1st Bn RWF to go back to England for an operation to straighten his nose so that he could use a gasmask, returned to join 2nd RWF the day after the retaliatory trench raid, just in time to go south. The Battle of the Somme had started.

The 2nd Battalion left the Cuinchy/Cambrin area by train on the 8th, arriving near Amiens at 7am two days later. By 15th July, they were at the south-east corner of Mametz Wood, in Brigade Reserve, and close to the 1st Battalion RWF, who had arrived on the Somme in time for the initial attack. Graves and Sassoon were able to meet. Here, they were surrounded by the dead bodies of the British who had fought to capture the wood, and the Germans who had fought equally hard to prevent them. Both men later wrote about the scene - Sassoon in "The Road", and Graves in "A Dead Boche".

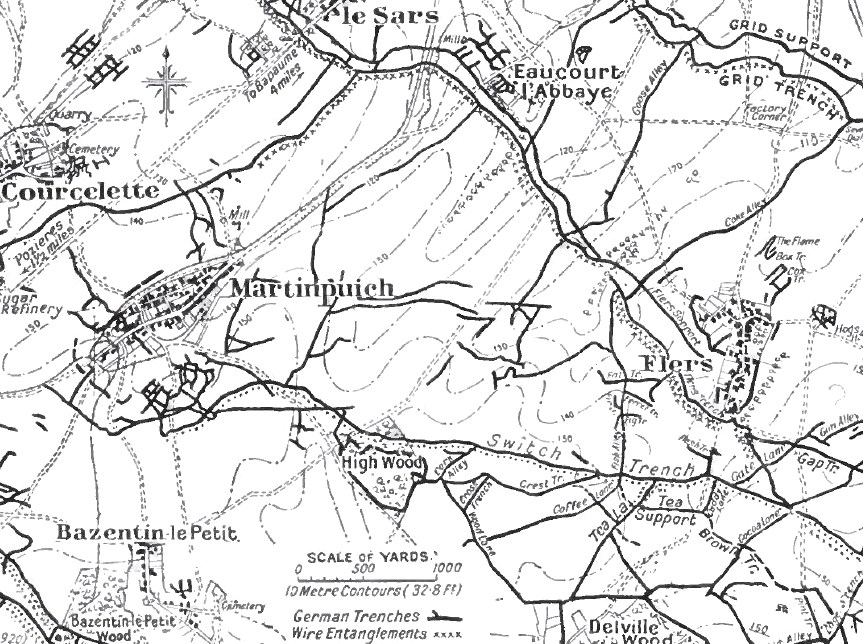

Over the next couple of days, forces were assembled for the next phase of the attack on High Wood; at midnight on 17th/18th July, the 2nd RWF were "aroused at midnight and moved to Bazentin-le-Petit" where they held the support trenches. Here they were "shelled heavily for about six hours from noon".

The attack on High Wood was launched at dawn on 20th July. Thirty Third Division attacked the wood itself, whilst 7th Division attacked just to the south-east (for the experience of the 8th Devons, see our article here)

The 2nd RWF were in the 33rd Divisional Reserve. At midnight they were woken again from their bivouacs and moved to Flat Iron Copse, southwest of High Wood. They were "heavily shelled from 3am to 8am", then intermittently until noon. Robert Graves records that:

The Germans put down a barrage along our ridge, and we lost a third of the battalion before the show started ... the German batteries were handing out heavy stuff, six and eight-inch.

Graves was badly wounded at this point and evacuated to England. Meanwhile the Battalion was ordered at noon to go up to High Wood to provide support to the first wave of the attack, reaching the wood about 2pm. According to the War Diary:

our attack succeeded in capturing and clearing the wood, including the Strong Point in the NW corner. Owing to the presence of [enemy] machine guns in the Switch Line [trench], a defensive line was dug 100 yards within the N edge of the wood.

At about 9pm the Germans began a counter-attack and an hour later the edges of the wood were heavily shelled. At 1am other troops were brought up to try to hold the position in the wood, and the 2nd RWF was withdrawn.

The War Diary reported that they had once again sustained heavy casualties:

Officers: one killed, one wounded and died of wounds, nine wounded

Men: 29 killed, 180 wounded and 29 missing

Amongst the men wounded on 20th July was Francis Jarwood. He was admitted on 20th July with "shell-shock" to No 23 Field Ambulance, then transferred to No 45 Casualty Clearing Hospital, still on 20th July, and then transferred the same day to No 12 General Hospital at Rouen. The timing of these transfers, all on the day on which he was wounded, suggests he may have been affected by the heavy shelling of the early hours of the morning, before the Battalion moved up to the Wood. This followed exposure to heavy shelling the day before.

The diagnosis of "shell-shock" became increasingly common during the first half of the war to account for a wide range of functional disorders occurring without organic injury, but apparently arising from proximity to explosions, or, more generally, the acute stress of combat. Francis' service papers provide no detail about his symptoms, so we don't know the form his illness took. Evidently he was not referred to England for specialist treatment, as was the practice in very serious cases, but remained in Rouen. After four weeks, he was posted to No 5 Infantry Base Depot at Rouen on 21st August 1916. On 10th September 1916, he returned to 2nd Bn RWF, when the War Diary records that:

Sergeant Prime and Sergeant Owen joined with thirteen other ranks.

By that date, the Battalion had moved to the northernmost part of the Somme sector, and was in billets at Humbercamps, three miles behind the lines. They had been through a long period of reinforcement, reorganisation and training, after the attack on High Wood on 20th July.

Shortly after Francis rejoined, they undertook a tour in the trenches near Hannescamps on 16th September for six days, but this was their only period in the front line during that month. At the end of September, they marched to the training camp at Lucheux, where they spent most of October on more training, introducing new arrivals to the trenches and preparing for the next "big push". As Peter Hart puts it:

Even though the Somme campaign was now moving deep into autumn and the onset of winter was approaching, there was still no question of abandoning the offensive. On the contrary, to General Sir Douglas Haig and the General Headquarters it seemed that the hammer blows of the previous months were bearing fruit at last. There were some indications that the German resistance was weakening and the tantalising possibility that they might at long last be on the very verge of collapse ... Haig ... was not prepared to give them any chance to recover... [he] had seen the Germans stop attacking just as they were about to break through to victory during the First Battle of Ypres and he had sworn never to make the same mistake.

Another concerted attack was planned all along the Somme front: from south to north, the Le Transloy Ridge, Pozieres Ridge, and the Gommecourt salient, and in the meantime smaller attacks took place to improve the British position at a tactical level and keep the enemy under pressure. Fresh troops were brought up for an attack on 12th October but battalions were under strength and inadequately trained. There were also many tactical failures - Peter Hart lists lack of surprise, difficult starting positions for the attacking troops, short and inadequate preliminary bombardment, and increasing use by the Germans of machine guns positioned well back behind their lines to escape the bombardment. A further attack was launched on 18th October; this also failed.

In addition, worsening weather meant that the conditions were very difficult. The Battalion began their move back to the front line on 18th October and by 21st October was in tents and huts in Méaulte. The following night they "lay in old and battered trenches" at Trones Wood. The War Diary observes that it was "very cold". On 23rd October, an attack was launched by 4th Division from Lesboeufs towards the village of Le Transloy. 2nd RWF were in reserve, moving into the trenches in Lesboeufs at 5pm on 24th October. There was continuous shelling and sniping during the night. For the next three days 2nd RWF remained in the trenches at Lesboeufs whilst attacks by the French, immediately to the right of the British position, were planned and then called off. They were finally relieved at 2.30am on 28th October.

The War Diary records the appalling conditions, as so many testimonies do of this period:

The weather conditions during the whole tour had been bad, the trenches were very wet and muddy and in the early stage of construction. Carrying parties were very heavy, ration and water parties having to go three miles from the line over ground much cut up by shell holes and in a bad state owing to the rain.

There were many wounded and dead of the 11th Brigade in the sector left from previous attacks by that Brigade. During the tour the Regiment evacuated about 20 wounded of the 11th Brigade and buried as many of their dead as was possible. We had contemplated and arranged for an attack each night on the German lines opposite ours but on each occasion were unable to carry the attack out.

On their way back from the front, they passed the night of 28th/29th October in shell holes at Guillemont, where they spent the day in "making cover for the men"; on 30th, they were between Trones and Bernafay Woods in bivouacs, where it was very wet and muddy and the cover was "very bad indeed". On 31st October, they were out of the line at Briqueterie, in quarters which were "bad as regards mud but the men are in tents and have blankets for the first time since leaving Trones Wood on 23rd".

Their relief did not last long - on 3rd November they were back in the trenches at Lesboeufs, and the next day they received orders to advance the front line towards the cemetery just south of Le Transloy. On the night of 4th/5th "an attempt was made by 2nd Lt Loverseed and a party of men from "B" Company to dislodge a packet of Germans occupying a position likely to cause great annoyance to a daylight attack" but it was unsuccessful and "heavy casualties incurred" (the numbers are not given in the War Diary). The following morning, at 11.10am, they moved forward, following a prior artillery barrage:

The Battalion was to push forward strong points under cover of the Barrage up to the [new forward trench] line we were to dig, and patrols still further forward for the purpose of closely reconnoitring the Le Transloy Cemetery Circle. The new line was not to be dug until dusk.

The War Diary reported that they were able to establish a new line 100 yards short of the objective "and were sapping out towards it"; on 6th November, "work continued and a good trench dug. Saps with ‘T' heads now only 15 yds from our original objective"; by the night of 6th/7th November, they had managed to dig "70 yards of continuous trench on the objective line".

On 7th November, they handed over to 1st Devons, and moved back to La Briqueterie Camp during a very wet night, then further back to billets in Méaulte.

But Francis had suffered badly from the conditions. On 10th November, whilst the Prince of Wales met the officers of the Battalion over tea, he was admitted to No 19 Field Ambulance with bronchitis and moved the same day to No 21 Casualty Clearing Station, at La Neuville, near Corbie. His condition worsened quickly - two days later he was in No 3 General Hospital at Le Treport, along the coast from Dieppe, from which he was invalided to England on the hospital ship Gloucester Castle on 15th November 1916. He was taken to the Seaforth Military Hospital, in Merseyside. On 30th November 1916, due to his condition, he was posted back from 2nd to 3rd Battalion RWF.

Death

During the next few weeks, Francis evidently failed to make progress. As he was in Merseyside, Edith was (presumably) able to visit him, but he was a long way from his mother and the rest of his family in Devonport. His father, Richard Ferris, was by now serving in HMS Blake - his elder brother Andrew was still in HMS Colossus.

On 11th February 1917, he was transferred to the Liverpool Stanley Hospital, in Stanley Road. He died the following day. His papers include a letter describing his condition when he was admitted:

This man was admitted at 2.0pm 11th February 1917 from the Military Hospital Seaforth. He was in a dying condition deeply cyanosed with marked dyspnoea suffering from Pneumonia and extensive capillary bronchitis.

He died 27 hours after admission at 5pm on 12th February 1917.

P M Powell MD

(Dyspnoea - shortness of breath)

A further letter (of illegible date) recorded:

In reply to your telephone enquiry it is difficult to say from the condition this man was in when admitted but it is probable that his death was accelerated by his military service.

from E W Osburn for M/O

Indeed, it is highly likely that, though dying of bronchitis in Liverpool, Francis was as much a casualty of the Battle of the Somme as any of those who had died in action.

The army duly recorded that he had served 5 years and 147 days of his six-year commitment to service in the Army Reserve.

Francis was buried in Toxteth Park Cemetery in the same plot where Edith's parents, his uncle and aunt Henry and Bessie, had been buried in 1910 and 1913. A new headstone was provided for his grave in 1991, by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Commemoration

The Dartmouth Chronicle of 23rd February 1917 carried the following announcement, placed by Edith:

Death:

Jarwood - February 12th, at Stanley Hospital, Liverpool, of bronchitis, Private Francis R F Jarwood, Welsh Fusiliers, with BEF 2 years, beloved husband of Edith, and second son of R and F Jarwood, Dartmouth, aged 24 years.

On 16th April 1917, the Army forwarded a letter of sympathy to Edith from the King and Queen (addressed incorrectly to Mrs Garwood). At that time she was still living in Birkenhead. On 5th September 1917, however, she married Robert Henry David, a stoker in the Royal Navy, at St Mark's, Ford, Devonport, and moved to Devonport. But by 1919 she had returned to Birkenhead and died there, aged only 23 in 1920. The memorial plaque and scroll produced for Francis Jarwood was returned to the Army undelivered.

Francis' immediate family remained in Devonport after the war: his father Richard survived the war, being demobilised from the Navy on 24th June 1922, but died six months later in Devonport. Francis' brother Andrew survived the war too. He married and settled in Plymouth. Francis' mother Fanny died in 1945 in Plymouth.

Though he had been listed amongst the "men of Dartmouth" serving in HM Forces in the Dartmouth Chronicle in January 1915, Francis was not commemorated on any of the public memorials in the town. He is on our database because of the obituary in the Dartmouth Chronicle.

For at any time I may come upon them, and find that long silence descended over them- their faces grey and disfigured - dark stains of blood soaking through their torn garments; all their hope and merriment snuffed out for ever, and their voices fading on the winds of thought, from memory to memory, from hour to hour, until they are no more to be recalled. So does the landscape grow dark at evening, embrowned with dusk, and backed with a sky full of gun flashes. And then the night falls and the darkness of death and sleep.

From the Journal of Siegried Sassoon, 13th July 1916

Sources

*Note: At the time of the First World War, the title of the Regiment was spelt "Royal Welsh Fusiliers", reverting to the old spelling of "Welch" in 1920. We have used the First World War spelling.

The War Diaries of the 1st and 2nd Battalions Royal Welsh Fusiliers are available from the National Archives, fee payable for download, references:

- 7th Division 22nd Infantry Brigade Royal Welsh Fusiliers 1st Battalion October 1914-November 1917: WO 95/1665/1

- 2nd Division 19th Infantry Brigade Royal Welsh Fusiliers 2nd Battalion August 1914 - November 1915: WO 95/1365/3

- 33rd Division 19th Infantry Brigade Royal Welsh Fusiliers 2nd Battalion December 1915 - December 1917: WO 95/2423/1

Francis Jarwood's Army service papers are available from subscription websites.

Naval service records are available from The National Archives, fee payable for download, references:

- Richard Ferris Jarwood: ADM 188/289/175831

- Andrew James Jarwood: ADM 188/993/2554

Goodbye To All That, by Robert Graves, revised edition published Cassell, 1957; Folio Society reprint, 1999

On the Trail of the Poets of the Great War: Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon, by Helen McPhail and Philip Guest, publ. Pen & Sword Books, 2001

The Journals of Siegfried Sassoon, viewable online at Cambridge University Library

"Shell-shock" revisited: An Examination of the Case Records of the National Hospital in London" by S C Linden and Edgard Jones, Medical History 2014 October, accessed online

The Somme, by Peter Hart, publ Cassell, 2006

Somme 1916, A Battlefield Companion, publ. The History Press, 2016

Toxteth Park Cemetery Inscriptions

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Jarwood |

| Forenames: | F R F |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 4404 |

| Military Unit: | 3rd Bn Royal Welsh Fusiliers |

| Date of Death: | 12 Feb 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 24 |

| Cause of Death: | Pneumonia and bronchitis |

| Action Resulting in Death: | |

| Place of Death: | Liverpool Stanley Hospital |

| Place of Burial: | Toxteth Park Cemetery, Liverpool |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | No |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Dartmouth Chronicle Obituary |