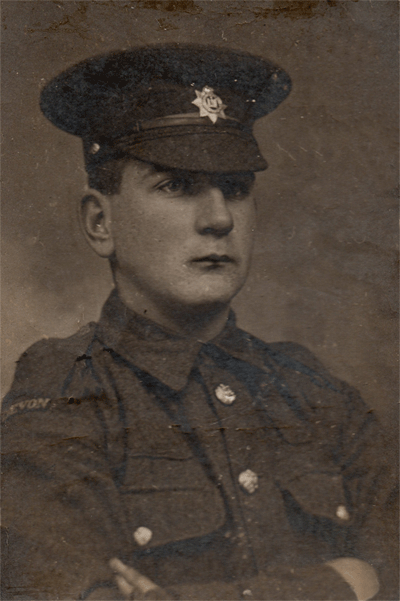

James Maddick Moses Tuckerman

Family

James Maddick Moses Tuckerman was born in Slapton on 10th October 1890 and baptised in St Saviour's, Dartmouth, on 30th November of that year. He was (according to Census records) the third son of Robert Henry Tuckerman and his wife, Fanny Susanna Maddick Moses.

Robert Henry Tuckerman was the youngest son of John Ash Tuckerman, who farmed at Langstone Farm, Blackawton, where the Tuckerman family had lived for many generations. Robert worked with his father on the farm until John died there in 1882. At the time of his marriage in 1885 he was still farming, but after this he evidently followed a number of occupations - in the 1891 Census he was recorded as a miller, at one of the three mills at Gara Bridge; by 1901, the family were living in Smith Street, Dartmouth, and he was recorded as a Timber haulier and Carrier; and in 1911, he was recorded as a stone quarryman.

James' mother, Fanny, was the daughter of James Henry Moses, a Master Mariner, and his wife, Sarah Jane Prescott. (The name Maddick came from James Moses' mother). James Moses was the son of a Brixham fisherman and pilot who had moved to Dartmouth around the time of his son's birth. James Moses had followed in his father's trade, but it was a dangerous calling - he was drowned age 29 in 1862, when Fanny was about a year old. Fanny's mother Sarah had married again, two years later. Her second husband, John Gilbert Sheen, was another mariner, and tragedy struck a second time when he too was drowned, when his ship was wrecked in the Bay of Biscay in 1874.

Sarah, twice widowed, was left with five children to bring up, three by her first marriage and two by her second. She supported herself by working as a Milliner, and Fanny also went out to work. She was recorded in the 1881 Census in domestic service as a parlourmaid, in the household of Stephen Jenning Goodfellow, a retired physician, and his wife Elizabeth, in "Swinnerton", Townstal (now Summer Hill).

In 1885, Fanny and Robert married in St Saviour's, Dartmouth. They were both aged 24. They settled first in Blackawton, where their first son, Robert Henry junior, was born in 1886. John Ash, named for his grandfather, followed in 1888; and after James Maddick Moses, named for his mother, her father, and her grandmother, in 1890, there were two girls - Armenia Olivia Prescott, named for Fanny's sister, half-sister, and mother, born 1893, and Frances Mary, born 1895. Their sixth and last child was George Edwin, named for his father's elder brother, born in 1899.

But between April and June of 1902, both Fanny and her younger daughter Frances died. Fanny was only 41, and Robert had young children to look after. Fanny's elder sister Sarah had lost her husband, William Prescott, five years earlier. She came to live with her brother in law, Robert, as his housekeeper, and to provide a home for his and her children - in the 1911 Census she and Robert were recorded living in 3 Charles Street, looking after his youngest son George, at the age of 12 still at school, and her second youngest son, also George.

The rest of the family, however, had dispersed. The boys did not follow their father's rural occupations but instead joined the services. Robert Henry junior had joined the Royal Engineers. In the 1911 Census he was recorded as a Telephonist, with the rank of Lance Corporal. John Ash junior had joined the Royal Navy as a Boy 1st Class in 1903. Armenia, by 1911, was living in Newport Street, Dartmouth, with her aunt Mary, her father's elder sister, who had not married, and was working with her as a dressmaker.

Service

Before the war

It was perhaps his eldest brother's example that led James to join the Army. His service papers have not survived. However, his service number, 8459, suggests that he joined the Devonshire Regiment in September 1907, approaching his seventeenth birthday. "Soldiers Died in the Great War" records that he enlisted in Dartmouth.

At that time, adult recruits had to be aged between 18 and 38, and were not meant to be sent overseas until they were 19. In 1907, the 1st Battalion of the Regiment was in the Far East and the 2nd Battalion was based at home in Devonport. James' first experience of Army life will have been garrison duties, training, and ceremonial events, such as the funeral in 1908 of Sir Redvers Buller (who had commanded British troops, including the Devonshire Regiment, during the Second Boer War).

James' chance to see the world came early the following year when the 2nd Battalion was sent to Malta. On 8th January 1909, they embarked on the Braemar Castle and arrived in Malta eight days later. There they were joined by a detachment of the 1st Battalion, which was on its way back from India; meanwhile a detachment of the 2nd Battalion (we don't know whether this included James) were sent to Crete. Here there was an international peace-keeping force, which had been set up in 1897, after fighting between Turkey and Greece over the island. Their posting there was short, however, since by July, diplomatic agreement had been reached to hand over the peace-keeping role to the civil authorities. The detachment of the 2nd Battalion left with due ceremony on 24th July 1909, arriving in Malta to rejoin the main body of the Battalion four days later, where they were quartered in Imtarfa.

The History of the Regiment observes that life in Malta for the 2nd Battalion involved many social occasions and a great deal of sport, but no important events. They remained there for three years (during which time their members, including James, were recorded in the 1911 Census); and then moved on in January 1912 to Egypt - first Alexandria, and then Abbassia, in Cairo. Apart from one company going on a short detachment to Cyprus, life was pleasant - a modicum of training, a great deal of social activity, and a great deal of sport. Pictures appeared in the Exeter papers of the Battalion marching past Lord Kitchener at the King's Birthday Parade in 1913, with a substantial contingent mounted upon camels; and of members of the Battalion picnicking in front of the Sphinx.

Outbreak of war

The Battalion was still in Egypt at the outbreak of war, and was first ordered to Ismalia as part of a force detailed to guard the Suez canal. The regimental history says that "though all kinds of rumours and alarming reports were current, nothing had occurred" by 10th September, when the Battalion was ordered to return to England. By 6 am the following morning the men were on trains to Alexandria and before nightfall had embarked on SS Osmanieh which sailed for Southampton two days later. Their journey home was untroubled, and they arrived in England on 1st October.

The Devons had been brought home as much needed reinforcements. Two new Divisions, the 7th and 8th, were being pulled together to add to the original six divisions of the British Expeditionary Force sent to France in August 1914. Both were formed in September and October 1914 by bringing together regular army units stationed at various points around the Empire.

The Devons were allocated to the 8th Division, which brought together three battalions from India, one from South Africa, another from Bermuda, another from Aden, and the rest from Egypt and Malta. Its engineers came from Egypt and Gibraltar, but its Artillery, Signal and Cyclist companies, and other divisional units, were improvised from other sources, as were its senior commanding officers. Reservists were quickly called up but completing the equipment, and bringing together all the units required, took several weeks. The concentration area for the Division was Hursley Park, near Winchester. The 2nd Devons were amongst the first to arrive. They were allocated to the 23rd Brigade, with the 2nd Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment, the 2nd Battalion Middlesex Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion Scottish Rifles (Cameronians).

The men had all returned from hot climates and were about to face the rigours of winter trench fighting in Flanders. Calls went out for help: the Mayoress of Exeter mounted an appeal in the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette to the "women of Exeter and Devon" to set to work without delay to ensure that the 2nd Devons received "1000 shirts, 1000 pairs socks, 1000 scarves and helmets, 1000 pairs woolly gloves or mittens, and also comforts - pipes, tobacco, and cigarettes". Although the weather in England through most of October was fine, when the 2nd Devons left Hursley for France at 2.30am on 5th November, they paraded and marched off "in torrents of rain and through a sea of mud", according to the Regimental History, a foretaste of what was to come.

The crossing from Southampton to Le Havre on the SS Bellerephon was quiet and the 2nd Devons reached France on the morning of 6th November. By this point (according to the 1914 Star Medal Roll) James had been promoted to Corporal. He was not the only man from Dartmouth on our database who arrived in France with the 2nd Devons that morning. Harry Ridges had joined sometime in 1908, and William Charles Webber sometime around 1911/1912.

France

The 8th Division was to concentrate at Neuf Berquin, two miles north east of Merville. The 2nd Devons arrived on 9th November but within two days were ordered up to the trenches south of Ypres, to relieve troops required to reinforce the Ypres salient, at the tail-end of the battle of Ypres. Most of the next four days was spent in "improving" trenches. On 17th November they rejoined the rest of the Division at Estaires. The 8th Division was to hold a portion of the front line around the village of Neuve Chapelle (the line went around the west side of the village, which was in German hands). Here they were at the southernmost sector of the front held by the British, which extended from the La Bassée canal, through Armentières, up to the area northeast of Ypres. (Shortly after, French divisions replaced British troops north and east of Ypres, and the upper end of the British line consequently moved south to Wijtschate).

According to the Divisional History, the entry of the 8th Division into the line "coincided with the gradual settling down of both combatants to the first winter of trench warfare". The trench lines were close, about 100-200 yards. Houses and other buildings still provided cover for snipers, and hedges and trees had not yet gone. Aside from these threats, the major source of difficulty was the weather - November was cold and very wet; on 18th November it started to snow, and three days later it was freezing hard. The troops were unacclimatised, and they lacked the equipment and experience which later in the war made trench life just about bearable. Notwithstanding the socks, mittens and vests provided by the women of Devon, frost-bite had accounted for more than 70 men sick within a few days.

The Battalion's routine consisted of short tours of a few days in the trenches, interspersed with similarly short periods of time in billets as reserve. The main focus of activity was to maintain and improve the trenches, but the Battalion was subject to both shelling and sniping, especially during the periods of handover and takeover, causing some casualties.

On 18th December, however, there was a more significant operation, to attack the village of Neuve Chapelle. It is described in Harry Ridges' individual story for he was severely wounded there, and died as a result. Total losses for the 2nd Devons were substantial - four officers killed and five wounded, and 121 other ranks killed, wounded or "missing".

We don't know how James fared during this first attack on Neuve Chapelle. Presumably he saw Christmas in the trenches with the rest of the Battalion. The 2nd Devons kept Christmas Day in billets on 23rd December. The war diary records "innumerable presents of plum puddings etc". On Christmas Eve they relieved the 2nd Scottish Rifles in the trenches: "very wet". On Christmas Day the Battalion's War Diary records:

Informal armistice during daylight. Germans got out of their trenches and came towards our lines. Our men met them and they wished each other a merry Xmas, shook hands, exchanged smokes etc

However, the "informal armistice" did not last long, for the War Diary goes on:

About 7.30 pm sniping began again. We had one man killed and one wounded. Hard frost.

During January and February 1915 the routine continued of short periods in the trenches followed by short periods in billets. The weather continued very cold and very wet. Though this was officially a "quiet" period, the Battalion was subject to steady attrition, particularly on takeover and handover. The War Diary reports the following:

| 1st January: | one man killed two wounded |

| 6th January: | one man killed one wounded |

| 12th January: | one man killed and one wounded |

| 13th January: | three men killed and two wounded |

| 14th January: | one man killed and one wounded |

| 17th January: | one man killed and two wounded |

| 18th January: | one man killed and three wounded |

| 19th January: | three men wounded |

| 23rd January: | five men wounded, one of whom died later |

| 24th January: | three men killed and six wounded |

| 25th January: | one officer and three men killed, six men wounded |

| 26th January: | four men wounded |

| 29th January: | one man wounded |

| 30th January: | one officer dangerously wounded (died the following day); one man killed, seven wounded |

| 31st January: | one man wounded |

| 1st February: | two men killed one wounded |

| 2nd February: | one man wounded |

| 4th February: | three men wounded |

| 5th February: | one man killed six wounded |

| 7th February: | five men killed four wounded |

| 11th February: | one man killed four wounded |

| 13th February: | two men killed five wounded |

| 15th February: | seven men wounded when billets shelled, one of whom died the following day |

| 17th February: | two men wounded |

| 18th February: | two men killed and two wounded |

| 22nd February: | four men wounded |

| 23rd February: | "casualties" (the War Diary is unspecific - CWGC's casualty database has one man from 2nd Battalion killed in action on this date) |

| 24th February: | one man wounded |

| 25th February: | one man killed, one wounded |

There were also some self-inflicted casualties. On 11th January, one man was wounded whilst in billets by friendly fire; on 20th February one man died while asleep in billets, from suffocation by fumes from a coke fire; and on 26th February two men died from severe wounds when a wagon load of "bombs" (early grenades) blew up in front of them.

On 27th February the Battalion received orders for a much needed "rest", and the following day they marched to billets in the Forest of Nieppe, at that time untouched by war, between Merville and Haverskerke. As the Regimental History puts it, they had been taken out to "fatten" for a coming battle. Once again, the target was the village of Neuve Chapelle.

At some point during this period, James was promoted to Transport Sergeant, responsible (under the oversight of the Transport Officer) for the transport section of the Battalion. In this role his major preoccupation would have been the daily care of the Battalion's riding, draught and pack horses; and the organisation of, and arrangements for, the six ammunition carts, two water carts, three general service wagons, and the Medical Officer's cart.

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle

In January the French and the British generals had agreed, whilst contemplating how best to break the stalemate on the Western Front, that joint offensives would be launched in the north against the Aubers and Vimy Ridges, and in the south in Champagne, targeting two of the key rail supply routes to the German front line, and - hopefully - threatening them with encirclement. When plans for a joint offensive failed (because he was unable to agree to a French request for British troops to take over more of the French line) Sir John French nevertheless pressed on with his plan for an attack in the British section of the line.

At the strategic level, the aim was to help relieve the pressure on Russia, on the eastern front, by opening up an offensive on the western front. Many German troops had been moved from west to east and consequently the British substantially outnumbered the German forces facing them along their section of the line. There was thus a significant opportunity, and Sir John French had decided to make Neuve Chapelle the centre of the British attack. If the village could be taken, the nearby Aubers Ridge could also be taken, opening up German lines of communication to attack. The current position of the line also had many weaknesses - as the Devons' experience of continuous attrition indicates - and so there would be tactical advantage too, even if the full strategic gain could not be realised. The date selected for the attack was 10th March.

The overall plan was, first, that enemy front-line trenches and certain rear strongpoints were to be bombarded heavily in preparation; second, massed infantry would then attack; third, an artillery "barrage" would be fired parallel to the front of attack once it was underway, to prevent German reinforcements moving forward; fourth, as the attack was taken further forward, reserves would then be brought forward to hold the position gained. This process would (ideally) continue until the Aubers Ridge, beyond the village to the east, could be gained and held.

The attack was to be carried out by the 8th Division on the left, to the north of the village, with the Indian Corps to the right, to the south of the village. The 7th Division were in reserve.

In the 8th Division, the 25th Brigade were on the right and the 23rd on the left. In the van of the 23rd Brigade were the 2nd Middlesex and the 2nd Scottish Rifles, with the Devons in support.

At 7.30am the artillery bombardment began, and after 35 minutes, at 8.05 am, the infantry attacked as the artillery moved the barrage forward. The 25th Brigade, attacking the village itself, made good progress and had taken the village by mid-morning.

The attack of the 23rd Brigade alongside them to the north was less fortunate. The heavy artillery to be used in the attack had arrived only the day before the battle and, with no experience of range or of terrain, the initial bombardment had completely failed to destroy the German positions. There were thus very heavy losses, especially amongst the 2nd Middlesex and the 2nd Scottish Rifles, as they attacked, but also amongst the Devons when coming up to assist. Further bombardment was ordered, which had the desired effect, and after hard fighting, the target positions were achieved by 1.30pm. The Battalion War Diary says "the Germans everywhere appeared to be well on the run".

To the south, the Indian Corps had also encountered stiff resistance in one section of the line, delaying the order for the general advance. Eventually this was given at 2.45 pm. But, as the Devonshire Regiment History says: "communication between the advanced troops and the formations in rear proved extremely difficult to maintain. Wires were cut or broken, the congestion of traffic behind the lines delayed runners and mounted messengers". Due to misunderstanding and confusion caused by these difficulties, the 7th Division did not come forward to take the attack further until much later in the afternoon, and was unable to make much progress, halting 200 yards in front of the Devons' line.

In addition, lack of effective communication between the first line of infantry in attack and the supporting artillery meant that an attempt by the Devons to move further forward earlier in the afternoon had been thwarted by shelling from British guns. The Regimental History comments: "The splendid opportunities which the prompt advance of reinforcements might have exploited thus gradually slipped away". At 3pm the Devons received orders to consolidate their position and they remained there for the next two days.

Overnight the Germans had brought up what available reserves they had and constructed a new defensive line. Fog prevented effective British artillery bombardment. Consequently the continuation of the British attack at 7am met heavy German fire "too great to be withstood". The Divisional history continues: "Telephone lines were cut and cut again faster than they could be repaired, and the constant fire ... made it almost impossible for runners to get through ... telephone communication between division and brigade and brigade and battalion was practically non-existent". No progress was made and casualties were heavy.

The 2nd Devons, meanwhile, remained where they were. The War Diary states:

Enemy had evidently brought up considerable amount of artillery and we were heavily shelled. Two shells falling in our HQ killed five signallers and orderlies and wounded six. "B" Company ... was heavily shelled in afternoon and had several casualties, otherwise position remained the same till evening, when we extended our left ...

Death

James was killed on the third day of the battle, 12th March. The precise circumstances are not known. On the morning of that day, the Germans counter-attacked, but this was repulsed. The War Diary reports that the Devons, still holding the position they had gained two days earlier, were once again "heavily shelled". "D" Company suffered several casualties, six killed and 26 wounded.

Later that day the Battalion received orders to cooperate with all other available troops in a renewed attack. They assembled and got into position. The Regimental History states:

It was a difficult move. The ground was unfamiliar, much cut up by ditches, trenches and hedges, and covered with dead and wounded ... The men, who had been without sleep since the night [before the start of the battle] were so exhausted that it was almost impossible to keep them awake.

The attack was due at 6.30pm, but was twice postponed. The opportunity was taken to reconnoitre, and a thorn hedge, very strongly wired, was found 150 yards in front of them. At 1.30 am, the Battalion started off, but had gone only 200 yards when it was stopped, and called back. "B" Company, however, being cut off from the rest of the Battalion by a dyke, never received the order to halt, and came under very heavy fire before it could be pulled back, with over 30 men wounded and missing.

Eventually, the attack was cancelled. Although the German bombardment continued, there were no further attacks on either side - the battle was over. The Aubers Ridge had not been reached - but Neuve Chapelle had been taken, and the line had moved forward. 11,652 British had been killed, wounded or were missing. John Keegan states German losses at about 8,600.

Commemoration

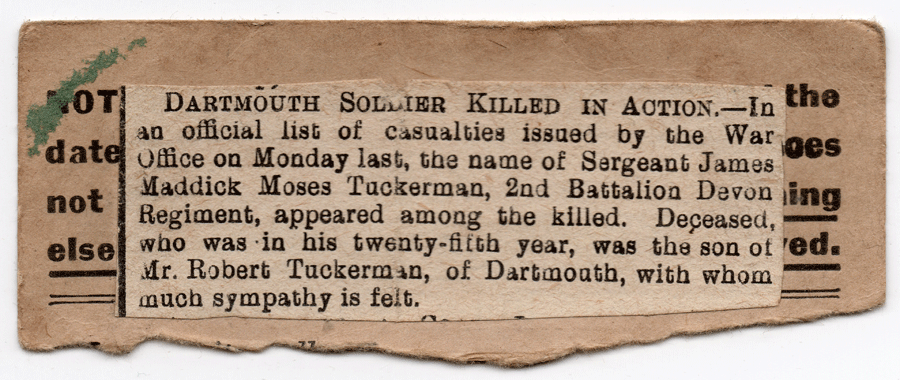

Though James died on 12th March, it took several days for the news to reach home. The Dartmouth Chronicle of 2nd April 1915 carried the following short piece:

Dartmouth Soldier Killed in Action

In an official list of casualties issued by the War Office on Monday last, the name of Sergeant James Maddick Moses Tuckerman, 2nd Bn Devon Regiment, appeared among the killed. Deceased, who was in his 25th year, was the son of Mr Robert Tuckerman of Dartmouth, with whom much sympathy is felt.

The following announcement also appeared in the same edition:

Deaths: Tuckerman - March 12th, 1915, killed in action James Maddick Moses, sergeant, 2nd Btn Devon Regiment, third beloved son of Robert and the late Fanny Tuckerman, aged 24 years and 5 months.

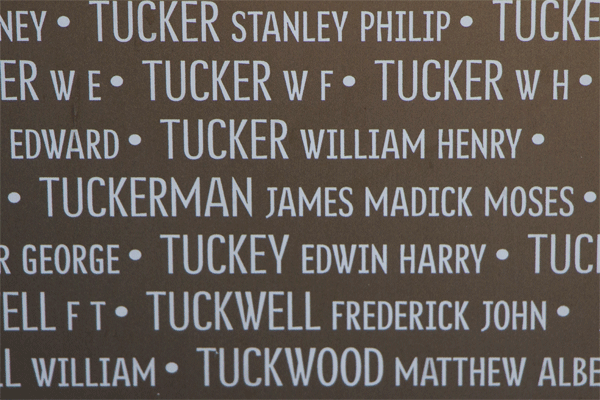

James is commemorated on the Le Touret Memorial, which commemorates over 13,400 British soldiers killed in this sector of the Western Front from October 1914 to September 1915, and who have no known grave.

As one of the 579,206 casualties in the region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, James is also commemorated on the new memorial at Notre Dame de Lorette, "The Ring of Memory".

James' name does not appear on any of the memorials in Dartmouth, although his father and his aunt continued to live in or near the town after the war. This omission is all the more striking as his aunt Sarah Prescott's youngest son, another James, James Henry Moses Prescott, James' cousin, appears on the War Memorial and the St Saviour's Memorial. He also reached the rank of Sergeant in the 2nd Battalion Devonshire Regiment and was killed in action in 1918. His story will be published in 2018.

Both James' elder brothers survived the war and had long careers in their chosen service.

We would like to thank James Tuckerman's family for permission to reporduce these images, downloaded from ancestry.co.uk.

Sources

The 2nd Devons War Diary, Martin Body, published by Pollinger in Print, 2012

The Devonshire Regiment, 1914-1918, C T Atkinson, published Exeter and London, 1926 (still in print)

The Bloody Eleventh: History of the Devonshire Regiment, vols 2 and 3, W J P Aggett, published by The Devonshire and Dorset Regiment, Exeter, 1994 and 1995

The Eighth Division, Lt Col J H Baraston, CB, OBE and Captain Cyril E Bax, 1926, reprint published by Naval and Military Press

The First World War, John Keegan, published Hutchinson, 1998

1915, The Death of Innocence, Lyn Macdonald, published Penguin Books, 1997

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Tuckerman |

| Forenames: | James Maddick Moses |

| Rank: | Sergeant |

| Service Number: | 8459 |

| Military Unit: | 2nd Bn Devonshire Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 12 Mar 1915 |

| Age at Death: | 24 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Neuve Chapelle, 10-12 March 1915 |

| Place of Death: | Neuve Chapelle, France |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Le Touret Memorial, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | No |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |