Reginald Pritchard Bawden

Reginald Pritchard Bawden was neither born, nor lived, in Dartmouth, though he had strong connections with the town - his mother was born there and his father lived there while young. He is on our database because his obituary appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle.

Family

Reginald Pritchard Bawden was born in Toxteth, Liverpool, early in 1898. He was the second son of Henry Bawden and his second wife, Bessie Adams.

Henry Bawden was born in 1854 on Achillbeg Island, just off the coast of County Mayo, where his father Isaac Bawden was a Coastguard (records sometimes show the name as Bowden). Isaac came originally from Antony, in Cornwall, and had served in the Royal Navy from 1841-1845, when he left to join the Coastguard Service (the service was formed in 1822, but not taken over by the Admiralty until 1856). He was sent to Ireland, where he did well, being soon promoted - Coastguard Service establishment records enable his career to be traced as follows:

- Jack's Hole, Co. Wicklow, Boatman, 13th September 1845 - 21st October 1846

- Keel, Co. Mayo, Boatman, 21st October 1846 - 22nd May 1847

- Mullaghmore, Co. Sligo, Boatman, 22nd May 1847 - 17th July 1847

- Achillbeg, Co. Mayo, Commissioned Boatman, 17th July 1847 - 4th April 1848

- Keel, Co Mayo, Commissioned Boatman, 4th April 1848 - 24th March 1852

Soom after his promotion and posting to Keel, he returned to England to marry. His wife, Agnes Priddis Moxhay, came originally from Brixham, though they married in St Germans, Cornwall. An attraction of the Coastguard Service was that accommodation was provided enabling the men to live with their families, so Agnes was able to go to Ireland too. However, even though they were able to stay together, familes were still required to make frequent moves.

In 1852 Isaac was promoted to Chief Boatman, and the family moved from Keel to Achillbeg, nearby, where Isaac had served before, and where they remained for nearly five years. Later Census records show that the couple's two older children, Charles and Henry, were born during this period, around 1852 and 1854. The Irish record known as "Griffith's Valuation" shows Isaac as the occupant of a "house and office" on Achillbeg.

On 17th January 1857, Isaac was moved to the station at Ventry, near Tralee, on the Dingle peninsula in County Kerry, to replace the Chief Boatman there, who had unfortunately drowned. The couple's third son, John, was born that year. The family stayed at Ventry until Isaac was promoted to Chief Officer of the 2nd Class on 31st July 1861. This meant a further move, to Whitegate, near Queenstown (now Cobh), on the east coast of Ireland, where he served as Chief Officer for just over a year. The family left Ireland for Devon on 19th August 1862. Isaac served as Chief Officer at Mothecombe, at the mouth of the River Erme, near Holbeton, until 2nd March 1865, and was then moved to the station at Dartmouth.

The Bawdens stayed in Dartmouth for about ten years. Isaac was able to buy a house in South Town, where the family was recorded in the 1871 Census. By that time, Charles and Henry had both gone into a similar line of work; Charles, aged 19, was an apprentice cabinet-maker and Henry, aged 18, an apprentice carpenter. John, aged 14, was working as a Clerk.

Close by, working as a servant and "nurse" in the house of Edward Marsh Turner, councillor and magistrate, and his wife, was Julia Kate Gillard, aged 16; the term "nurse" most likely meaning that she helped with the small children in the household. Julia was the daughter of Thomas Gillard, a mariner, and his wife Caroline, and came to Dartmouth from Salcombe. She and Henry Bawden married on 27th May 1875, at St Petrox in Dartmouth.

However, by the time of Henry's marriage, his father's term in Dartmouth had come to an end, and the family had moved to Merseyside. In the 1875 Electoral Register for Devon, Isaac Bawden was still entitled to vote in Dartmouth, because of his ownership of a "freehold house and garden" in South Town; but the register showed that he had moved to 124 Wellington Road, Toxteth Park, Liverpool. Henry therefore came back down from Lancashire to Dartmouth for his wedding. He had finished his apprenticeship and was working as a joiner in Southport. Henry and Julia settled in Merseyside.

Soon after their marriage, Henry's mother Agnes died and was buried in Toxteth Park Cemetery, on 11th September 1875. Henry and Julia suffered another bereavement when their first child, a girl, died before she could be named, in 1876. But by the time of the 1881 Census, they had two more children, William Henry, born 10th April 1878, and Florence Ida, born 12th February 1880. At the time of the 1881 Census, Henry, Julia, and the two children lived in 40 High Park Street, Toxteth; Isaac, now retired and a widower, lived with them. Henry continued to work as a joiner.

Shortly after the Census, Henry took on a chandler's business at 481 Mill Street, a shopping street in Toxteth. Florence Ida was baptised at St Cleopas, nearby, on 30th October 1881, and the St Cleopas registers also record:

- John Percy, born 29th December 1881, baptised on 9th April 1884 with

- Charles Francis, born 21st December 1883

- Ernest, born 8th March 1886, baptised 19th May 1886

Isaac Bawden died in 1886, and was buried in Toxteth Park Cemetery, with Agnes, on 23rd November.

For Sidney's baptism, Henry and Julia returned to St Paul's, Princes Park, on 3rd February 1889 (he was born on 30th October 1888); but their fifth son, Harold Edmonds, born 11th May 1891, was baptised on 15th July, back at St Cleopas. Sadly, he died when 10 months old, and was buried with his grandparents in Toxteth Park Cemetery on 22nd February 1892.

After Harold's death, Henry gave up the chandlery business, and obtained work as a foreman joiner. The family moved to 37 Fairfield Street, in West Derby, Liverpool, where Julia gave birth to a daughter, Olive Kate, on 6th June 1893. She was baptised at St Anne's, Stanley, on 14th June. But her mother failed to recover from the birth. Julia Kate was buried with Isaac, Agnes, and her little boy Harold, on 11th July. Olive Kate did not long survive her mother's death. She was buried with her mother on 26th July, aged only six weeks.

Henry was left with six children to care for, between the ages of four and fourteen. For a second time, he found a wife in Dartmouth. Early the following year, in Toxteth, he married Bessie Adams.

Bessie was the second of four daughters of Andrew Soper Adams, a fisherman, and his wife, Sarah Ann Blamey. Andrew was from Dartmouth and Sarah Ann from Brixham. Bessie was born on 8th May 1864, and baptised at St Petrox aged three, on 20th November 1867, with her older brother John Henry and younger sister Sarah Ann.

She was ten years younger than Henry Bawden. In 1871, when the Bawdens were living in South Town, she was living with her grandmother, Elizabeth Blamey, in Higher Street; her father and mother lived along the same street with the rest of their children. Whilst it is possible that she and Henry knew one another at that time, it seems more likely that some mutual friend put them in touch after Julia's death. By the time of the 1881 Census, Bessie was working as a Cook, in Kingswear, for a Scottish merchant, and his wife, Samuel and Emma Malcolm; the 1891 Census recorded her working in South Town as "Servant in Charge of House", for Jane Bailie, a widow.

Bessie's eldest sister, Ann Maria, had died in 1889, but, despite moving to Merseyside, she seems to have remained closely in touch with her other two sisters, Sarah Ann and Fanny. Fanny married Richard Jarwood in Dittisham in 1891, and their son Francis Richard Ferris Jarwood is also on our database. Sarah Ann married William Knapman in Stoke Fleming, in 1897, and was the person who placed an obituary for Reginald, Bessie's son, in the Dartmouth Chronicle (see below).

Bessie arrived in Liverpool to a ready-made family, and soon she had children of her own. By the time of the birth of her first child, Harry Harold Priddis, on 3rd November 1894, the family had moved back to Toxteth, and were living at 17 Wordsworth Street. Henry continued to work as a foreman joiner. Edith Irene Woodman was born in 1896 and Reginald two years later, both in Toxteth.

By the time of the birth of their next child, Agnes Kate, in 1899, Henry and Bessie had moved across the River Mersey to Littledale Road, Wallasey. At the time of the 1901 Census, they lived at 29 Percy Road; Henry was still working as a foreman joiner, and his eldest son William also worked as a joiner. Florence was still at home, no doubt helping Bessie with the younger children; Charles was a butcher, and Ernest, aged 15, a baker. Sidney, Harry, and Edith were of school age, while Reginald and Agnes were the babies of the family, at three and one. John Percy, Henry and Kate's second son, was not recorded at the family home, and may already have been working as a seaman in the merchant navy - he appears on several Liverpool Crew Lists in 1903.

Reginald thus grew up in a large family, which changed continually over the next few years:

- Bessie Phillis was born in 1901, and Eric Isaac in 1902,

- William married in 1903

- Henry and Bessie's fourth son, Redvers, was born in 1904

- Sidney left to join the Navy, in 1905, as a Boy 2nd Class

- Henry and Bessie's fourth daughter, and last child, Jeannie, was born in 1906

- Charles died, aged only 24, in 1908, and was buried with his mother, baby brother and sister, and Henry's parents, in Toxteth Park Cemetery

Then, on 3rd February 1910, at the relatively young age of 56, Henry Bawden died, at the family home, 5 York Road, Seacombe, Wallasey. He was buried near the rest of his family, in Toxteth Park Cemetery. Just a few weeks later, on 15th March 1910, Sidney was invalided out of the Navy with nephritis, and had to return home. Bessie was left a widow, responsible for the whole family, and the 1911 Census indicates that she may have found this a struggle. At the York Road house (which was quite large, with nine rooms (including the kitchen)) there were Bessie herself, and seven of the children - in order of age:

- Ernest, age 25, working as a barman

- Sidney, age 22, now working as a gas contractor for "Borough Council"

- Harry, aged 16, an apprentice signwriter

- Edith, aged 15, still at school

- Reginald, aged 13, at school

- Redvers, aged 6, at school

- Jeannie, aged 5

But in addition, the house also accommodated Bessie's sister in law, Jane Bawden, the widow of Henry's brother Charles; Bessie's nephew Francis Richard Jarwood, from Dartmouth, (already referred to above), working as a grocer's assistant; and a boarder, one James Mason, a housepainter - presumably to help bring in additional income.

Florence was now working in domestic service, not far away in Egremont, so was no longer at home; but Bessie had also sent some of her younger children away to school. The Census recorded both Agnes Kate and Bessie Phillis, aged 11 and 9, as "inmates" at the Liverpool Female Orphan Asylum, in Myrtle Street. Admission was limited to girls born within seven miles of the centre of Liverpool, and aged between 7 and 11 on entry - Agnes and Bessie junior were in the right age group and this presumably was why they were sent away rather than the older or younger children.

Other records show the admission of Eric Isaac on 29th June 1910, to Ripley Hospital School, Lancaster. This was a school founded by Mrs Julia Ripley, in memory of her husband Thomas, born in Lancaster and a wealthy Liverpool merchant. The school (which included excellent facilities) was founded to educate children whose parents had to have lived within 15 miles of Lancaster Priory or 7 miles of Liverpool Cathedral, for at least two years immediately preceding the father's death. Children were admitted in order of priority - orphans first, motherless or fatherless second, and the remainder from "indigent" parents. Although Eric met the second criterion, the admissions register records, under "circumstances of child": "mother poor". Eric stayed the course, leaving in 1916, when aged just short of fourteen, to be apprenticed as a shop assistant; but his younger brother Redvers, admitted to the same school on 3rd July 1912, and on the same grounds, was sent home, due to "chronic infirmity".

Then Bessie herself died, on 1st June 1913, aged only 49, and was buried with Henry in Toxteth Park Cemetery. Reginald, and all his brothers and sisters, had lost both their parents in three years. Nonetheless, some measure of stability may have been achieved, because it appears from various records that the family stuck together, and continued to live at 5 York Road for some considerable time. Although Florence married in 1914, it seems she did not leave York Road, and so probably took on the role of looking after all the younger members of the family.

The comings and goings continued. Sydney, clearly missing the sea, went into the merchant navy to work on "foreigngoing steamships" - records show that he was in Australia during the first half of 1914, obtained his 1st Mate's Certificate in Liverpool in 1915, and his Master's Certificate in 1916. Harry completed his apprenticeship, and became a signwriter. Reginald went to work at the Liverpool Corn Exchange, at the commercial heart of the city.

When the war broke out, the younger boys were still at school. Sadly, Ernest died aged 29, only a few days after the beginning of the war, on 15th August 1914. He was buried with Henry and Bessie in Toxteth Park Cemetery.

Service

Reginald's cousin Francis, who was a member of the Army Special Reserve, was mobilised at the start of the war, and by 2nd November 1914 was in France with the 1st Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and soon on the front line. Perhaps this encouraged Reginald to volunteer. He was about sixteen and a half at the outbreak of war, and although many boys of this age did enlist, the minimum age for recruitment into the Regular Army was eighteen, with nineteen the minimum age for going overseas on active service. However, the Territorial Army would take boys at seventeen, and sometimes provided a faster route to the front line, notwithstanding limitations on age for going overseas.

Reginald's Army service papers have not survived, but the Medal Roll of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, with whom he was serving at the time of his death, shows that he enlisted in the 3/5th Battalion of the King's (Liverpool) Regiment. "Soldiers Died in the Great War" records that he lived in Seacombe, and enlisted in Liverpool.

The 5th Battalion of the King's (Liverpool) Regiment was a Territorial Force Unit, which was mobilised when the war began. The 2/5th Battalion was formed in September 1914 initially as a second line Battalion, for those TF members who had not volunteered to serve overseas, were not fit enough to go, or were too young to go. However, in November 1914, TF units were told to raise third line Battalions, in place of first line units going overseas, and in January 1915, reserve battalions were authorised to recruit over establishment with a view to forming a further reserve Battalion. The 3/5th Battalion was formed in Liverpool in May 1915. So it seems likely that Reginald enlisted in the Territorials soon after his seventeenth birthday, and was posted to the 3/5th when, or soon after, it was formed.

The introduction of conscription in January 1916 meant that overseas service became compulsory in the Territorial Force. But as a Reserve Battalion, the 3/5th King's (Liverpool) did not go overseas. By August 1916, Reginald, whilst still in the King's (Liverpool), and though he was still not yet nineteen, was in France, "attached" to the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. Published casualty lists show that he was wounded twice - his name appears in lists of 28th August 1916 and 2nd October 1916.

The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry Medal Roll also records that Reginald transferred from the King's (Liverpool) to the 2/1st Buckinghamshire Battalion, with the service number 5438. It also shows that, as a member of the Territorial Force, he received a new service number, 267176, on 1st March 1917. This falls within the block of numbers allocated to the Buckinghamshire Battalion, within the Ox & Bucks Light Infantry. So his formal transfer to the Buckinghamshire Battalion presumably took place some time after early October 1916, when he was reported wounded for a second time, still with his King's (Liverpool) number.

No information has yet come to light enabling us to identify which Ox & Bucks Battalion he first joined in France, but it seems reasonably certain that he was with the 2/1st Buckinghamshire Battalion by, say, November 1916; and it is reasonable to assume that he remained with them until at least the time at which his new Territorial Force number was allocated.

According to the Oxford and Bucks Medal Roll, Reginald was serving with the 6th Battalion, Oxford and Bucks LI, at the time of his death. His gravestone, however, identifies him as a member of the Buckinghamshire Battalion (see below), so perhaps his period with the 6th Battalion was also an attachment, or he had not been with the 6th for very long at the time of his death.

The 2/1st Buckinghamshire Battalion

The 2/1st Buckinghamshire Battalion was formed in 1914 as a second line unit of the Territorial Force. It went to France in May 1916, with the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division, and went into the front line for the first time near Laventie (between Bethune and Armentieres). The first major action in which it was involved was the Battle of Fromelles, intended as a subsidiary and diversionary attack to the Battle of the Somme, underway further south. To attempt to further destabilise the enemy, and prevent them moving reinforcements south, an attack was launched on the Aubers Ridge, against heavily-defended German positions overlooking allied lines. Two divisions were used, the Australian 5th and British 61st. The attack was a disaster with very heavy casualties, and the 2/1st Bucks was no exception. The Battalion had gone into action with 20 officers and 622 other ranks; losses were, in total, 322.

The time needed to rebuild and reorganise the 61st Division was such that it was not used in a major attack for some time, being limited to trench duties. In November, the 2/1st Bucks began their transfer to the Somme. The War Diary records that, at Barly, west of Arras, where they stopped for several days whilst en route, the officers diverted themselves with a fox hunt, with hounds owned by a local farmer. "There was a great scent, but a poor country". The fox was not a casualty. A few days later, there was another hunt: "[this] was rendered all the more enjoyable by its contrast to the daily routine and by the noise made by the guns at the Somme front, which could be plainly heard throughout, and which served to make this hunt a unique experience". Once again, the fox survived.

On 20th November, they arrived on the battlefield, and the " "scenery" east of Albert was seen for the first time by all ranks". They went into the line on 26th November near Mouquet Farm for four days, suffering eight casualties - two men killed and six wounded.

Their next tour in the front line began on Christmas Eve. There was certainly no Christmas Truce in 1916 - the Battalion War Diary recorded:

Xmas Day. After a period of quietude every gun on the 5th Army front suddenly opened fire of the Bosche at 8am. One round per gun. This was repeated at 12 noon and 5pm. The Batt. very wet and muddy but quite cheeful. Xmas greeting sent to 1st Batt [who were nearby].

They were relieved on 28th December, but the process took a very long time, owing to the incoming Battalion becoming stuck in the mud. They eventually arrived in their billets "wet through and exhausted". However there had been no casualties, and they had "received congratulations for good patrol work".

After a couple of weeks in support, they marched to their training and rest area at Gapennes through heavy snowstorms: "The Battalion thus marched back from the Somme almost to Abbeville without losing a man". They spent the rest of January and the first part of February resting and training, and began their move back towards the front line on 13th February, this time covering much of the distance by train.

They took over the line from a French Regiment at Deniecourt, south of the Somme river, near Peronne, on 19th February, remaining there until 2nd March. When they arrived: "All available men [were] engaged in clearing trenches which are falling in after the thaw". Four men were wounded on 23rd, and two on 25th. Three days later there was a sudden enemy raid on the Battalion on their left; "After heavy bombardment enemy got through our line of resistance. Bombed dug-outs causing over 30 casualties and took back over 20 prisoners including two officers". However, the following day was quiet and they were relieved on 2nd March, returning for another tour between 9th - 15th March. Here their main preoccupation was the effects of the continuing wintry weather:

Deep snow reduced [the trenches] to state of ditches again however during this tour work was concentrated on the trenches and they were kept open for all necessary traffic.

On their last day, they attempted a trench raid of their own, but the enemy post they had targeted was more strongly held than they had expected, so they had to withdraw. One NCO was killed.

On 18th March, the War Diary reported that the rumours of the German withdrawal (to what is now called the Hindenburg Line) were confirmed, and suddenly the Battalion was on the move. The German Army had implemented a "scorched earth" approach to make the pursuit as difficult as possible, so for the next ten days:

The Battalion was engaged repairing roads and filling in Mine Craters ... Villages passed through [were] found in most deplorable state, the Hun having done [every kind of] deliberate damage conceivable. Buildings burnt to ground, trees cut down, wells contaminated with filth.

By the end of March, they were resting at the village of Tertry, south-east of Peronne. On 1st April, they received orders to move into the line at Soyecourt, to take part in an attack on German positions, from the embankment of the railway running northwards from Vermand. This was the Battalion's first significant attack since the previous July, and the War Diary describes it in considerable detail. They attacked on a two-company front at dawn, without very much time to prepare. D Company, on the left, "went forward without opposition". C Company, on the right, had a harder time. They hugged the artillery barrage too closely and advanced too quickly, so casualties were caused by shellfire; and in addition, they briefly came under friendly fire from the neighbouring Battalion to their right, who in the half-light, apparently mistook the Bucks men for the enemy. However, the enemy positions were taken, and some prisoners were captured. Casualties were one officer and eight other ranks killed, and one officer and 29 other ranks wounded.

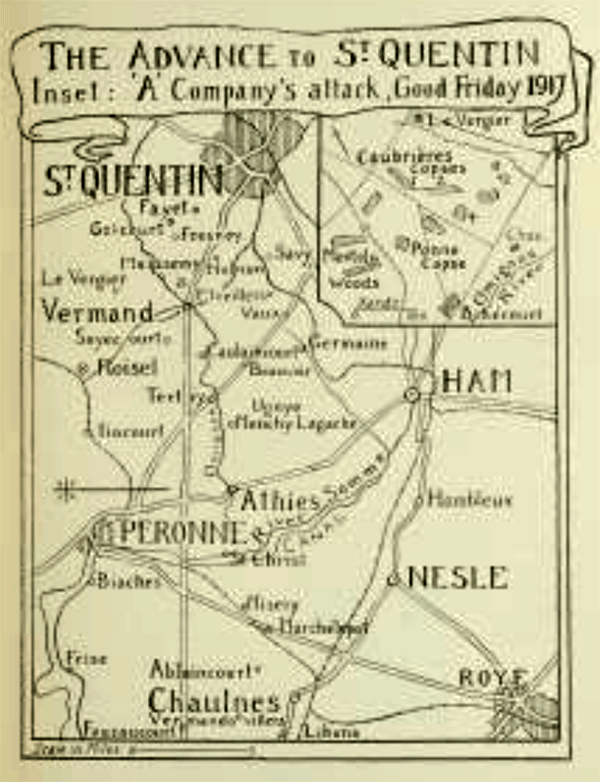

On 3rd April, the Battalion took Caubrieres Woods, which was found to be unoccupied by the enemy, and that night was relieved by the 2/4th Oxford and Bucks, who took the advance further forward. A map of the area concerned is included in a memoir written by Captain G K Rose, MC, of the 2/4th.

After this, the 2/1st were billeted in Caulaincourt, "an utter ruin"; shacks had been constructed out of salvaged corrugated iron, and many were not water-proof. Unfortunately, the weather was wet, with hail, rain and snow.

On 7th April, they returned to the line. The previous night, an unsuccessful attack had been made upon the German positions at Le Vergier, described in Captain Rose's memoirs. The 2/1st Bucks cautiously sent out a patrol to reconnoitre the enemy front line, and, to their surprise, found it empty. They took the trench, and at dawn, the Le Vergier garrison was seen to be withdrawing.

On 10th April, they returned to Tertry, and from there marched to Offoy, on the Somme, which, after everything they had seen, was notable for the absence of destruction. The 61st Division was relieved the following day, to return ten days later to hold the line opposite St Quentin. In the sector where the 2/1st Bucks Battalion was located:

An outpost line is held by one battalion of the Brigade. This outpost line runs approximately 1000 yards east of the village of Fayet, and then curves in a SW direction just north of the town of St Quentin. This line, including the village of Fayet comes under close observation from the high buildings of the town. The main resistance line runs approximately 800 yards in front of the village of Holnon, which is also under observation from St Quentin.

The 2/1st Bucks spent two days working on the resistance line, which was "far from complete" and then moved to the outpost line, on 23rd April. This line "forms an unpleasant salient and accordingly receives a large amount of hostile artillery fire". On 25th April, the line was taken forward towards Cepy Farm, and the following evening, an enemy attack on the outpost line was successfully fought off, before the Battalion was relieved and moved back to working on the resistance line.

In early May the 61st Division was relieved by the French, and the 2/1st Bucks went into billets at Germaine, well behind the line, moving later to Talmas, near Amiens, for rest and training. On 21st May they were billeted in Barly, where the officers had so much enjoyed their hunting the previous November, and were welcomed back by the inhabitants. They were then moved up to the Arras area in early June, for a short tour in the front line east of Guemappe, on the Arras-Cambrai road. They spent most of their three days on work to improve trenches and lay wire, and afterward spent the rest of the month in training.

6th Battalion Oxford and Bucks

There is nothing in the 2/1st Battalion's War Diary to give any clue about when, or why, Reginald moved to the 6th Battalion Oxford and Bucks. They were part of 20th (Light) Division and had also been involved in following up the withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line. Their War Diary records that, some time during June, they received a draft of 40 reinforcements - perhaps Reginald was one of these, because no further drafts were recorded until after the action in which he died.

On 21st July, they moved from rest billets in Montrelet, France, by train to Hopoutre, in Flanders, and marched to Proven Camp, near Poperinghe, as part of the preparation and build-up to the Flanders Offensive. Also in the 20th (Light) Division was the 10th Rifle Brigade, including William Burnell, who arrived in Proven the previous day.

The 6th Battalion was not required for the initial attack, on 31st July, as they were in reserve, so training continued up to, and beyond, the beginning of the battle. (For an account of the first day of the Battle of Third Ypres, see the stories of Richard Henry Goodman Carder, who was part of 51st Division, attacking north of Ypres, and William John Farrow Bates, part of 8th Division, attacking east of the city.)

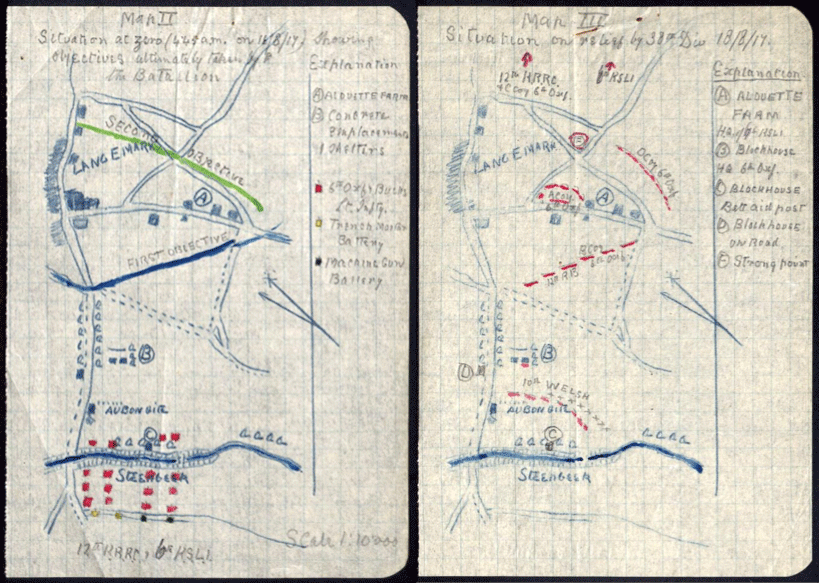

The 6th Battalion remained in camp near Proven until 5th August, when they were moved forward by train to Elverdinge, north-west of Ypres, and marched from there to a wood near Makaroff Farm, where they bivouaced. Parties of 1 officer and 3 NCOs and runners from each company went in turn to reconnoitre the ground up to the front line, but visibility was poor and not much was learned. The 20th (Light) Division was to be involved in the action following up the assault of the first day; their task was to take the village of Langemarck, beyond the River Steenbeek.

The conditions were extremely challenging. In his diary, the Battalion Intelligence Officer, 2nd Lieut Willes, wrote on 7th August: "The country on either side of the Steenbeek resembled what I imagine Sodom and Gomorrah looked like more than anything else". The plan of attack was discussed by the officers the following day, while the rest of the Battalion was engaged in working parties pushing trucks of stores for filling up forward dumps. The advance pack-pony lines at Saragossa Farm were shelled on 9th August, and one mule was killed; on 11th August, two men were killed and nine wounded. 2nd Lieut Willes spent a great deal of time liaising with other Battalions involved in the planned attack on Langemarck: "Nothing has been left undone with regard to this attack to make the liaison as complete as possible".

On 12th and 13th August, the 6th Battalion practiced the attack. On 14th August, according to the War Diary:

59th Brigade made an attack at dawn with the object of establishing themselves on the east bank of the Steenbeek and then give us a better "jumping-off" place for our attack on the 16th. They were tolerably successful, but the strong point at Au Bon Gite still remained in the hands of the enemy.

William Burnell, already referred to, was killed during this attack - for a description of the 10th Rifle Brigade's action, see his story here.

At 8pm, 6th Battalion left camp and moved into the line, into trenches west of the Steenbeek. Towards midnight on 15th August, they moved into position, ready for the attack at 4.45am on 16th August. "A" Company was on the left, with "C" Company behind them, and "B" Company on the right, with "D" Company behind them. Four platoons of the 12th Rifle Brigade provided "moppers up", one for each company; and one company of the 11th Rifle Brigade was given the task of dealing with the Au Bon Gite stronghold (which had provided 10th Rifle Brigade with considerable difficulty two days earlier). The two forward companies were on the east bank of the Steenbeek, having moved across in small groups so as not to betray their presence. The other two companies were on the west bank. Royal Engineers helped with laying the bridges, with the aim of getting them all in position before zero-hour.

The Battalion War Diary describes the attack:

Precisely at that hour the 11th Rifle Brigade put up a smoke barrage on Au Bon Gite and rushed forward to the assault and our first wave moved out and got well under the barrage, which started just on the far side of Au Bon Gite.

At the same time the remainder of the leading Companies successfully crossed the Steenbeek on the portable bridges which had been laid for the purpose during the night.

A & B Coys had been detailed to take the first objective (the Blue Line) and C & D Coys the second objective (the Green Line).

The two left Coys met with the most opposition, as they not only had to get past Au Bon Gite but had also other strong positions on their front (including the Blockhouse marked A on sketch). They also had the most ground to advance over, the mud in places being fearful.

The first objective was reached with trifling loss to the first Companies.

When the time came to move forward to the 2nd objective, D Coy got up their to time and with little loss. C Coy were somewhat late, but the whole line was eventually carried and consolidation proceeded with ...

The barrage appears to have worked excellently throughout. About 35 prisoners were taken at Au Bon Gite and a similar number at Blockhouse A.

At about 8pm, C Coy was sent to assist 12th King's Royal Rifle Corps forward in the "Red Line", and remained there for two days. A threatened German counter-attack was successfully prevented.

The Battalion War Diary includes the following sketches of the attack and of the positions reached.

2nd Lieut Willes provides a vivid description of the attack in his diary:

At 4.45am it sounded as if someone had been careless about leaving the lid off hell. The scene beggared description. It was just light enough to see one's way. The first thing that struck me was the immense variety of fireworks that the Hun was sending up. There was every known variety of Very light, and some I had not seen before. In fact, the only thing that he did not send up was a set-piece, with a portrait of the Kaiser, and God bless our Home in golden rain ...

The Au Bon Gite concrete block-house ... had loopholes for machine guns, was irregular in outline, but wonderfully well sited. Around it were five or six smaller posts, and from it to the stream a barbed-wire entanglement ran diagonally in such a way as to break up any attacking party ... With the smaller block-houses in the vicinity, there was formed a kind of triangular position of immense strength, and absolutely impervious to artillery fire. The capture of Au Bon Gite seemed well-nigh impossible; the general advance went on regardless of it, and it was perhaps this fact that upset the calculations of the enemy and caused him to surrender about an hour after the attack had been launched. Captain Slade and his company of the 11th RB, with the aid of a smoke barrage, succeeded in getting under the walls, and after much discussion, the defenders agreed to surrender, when 32 Germans were made prisoners and two machine guns captured. Had they stuck to their post could have absolutely hung up the attack of half our Battalion frontage...

Our first wave moved forward with parade-ground precision, getting well up to the barrage ... and the rear platoons came over the bridges with perfect steadiness, taking up their correct dressing, and moving on as they got their distance ... Our advance was well and steadily carried out. The two left companies suffered heaviest all the way, due to the fact that Au Bon Gite and other positions were firing on them as they advanced ...

Shortly after the attack, he visited the Blue and Green lines, to discover:

A Company: estimated casualties, 40, up to that time; company commander wounded; well dug in but getting badly shelled on left

B Company: 17 other ranks killed or wounded; one officer wounded

C Company: 54 other ranks not accounted for, but not believed all killed or wounded; company commander wounded. Connected up with Somerset LI on left.

D Company: 40 other ranks lost. Well dug in; connected up with 7th Dorsets on right

His verdict on the engagement was that:

To the military student the fight itself has no special interest. It was merely the conventional advance well carried out. But as an example of troops forming up under the noses of the enemy without shelter trenches, or indeed, any shelter, and with nothing to guide them, it will, I venture to say, stand for long in military history among the offensives of the war. It is an excellent example of what may be done with well-disciplined and well-officered troops.

The Battalion was relieved during the night of 18th/19th August, returning to the camp at Malakoff Farm. Although the attack had succeeded, casualties were heavy. According to the War Diary, their losses were:

Killed or died of wounds: 33 other ranks

Wounded: 3 officers and 148 other ranks

Wounded & missing: 4 other ranks

Missing: 4 other ranks

Death

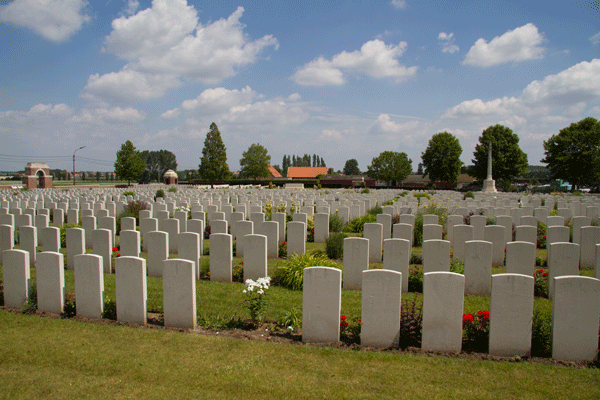

Reginald was one of those killed in this action. According to Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, he was first buried as an "unknown british soldier", with his grave identified with a cross, but date of death unknown, in a battlefield or small burial ground near Langemarck and Poelkapelle. Soon after the Armistice these graves were brought into Cement House Cemetery, in Langemarck, and it appears that his body was identified then. He was identified as a member of the 2/1st Buckinghamshire Battalion, rather than of the 6th Oxford & Bucks, with whom he had been serving.

His brother Harry, who had enlisted in the Royal Field Artillery a few months after Reginald, authorised the engraving on the headstone of the words:

A Tender Thought A Silent Tear Keeps His Memory Every Near.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission records also show that, as one of those dying in the Ypres salient with an unknown grave, his name had been included on one of the panels of the Tyne Cot Memorial. When his body was identified, and the headstone engraved, his name was removed from the panel.

The Liverpool Echo of 15th September 1917, and the Liverpool Daily Post of 17th September 1917, carried the same short note of his death, presumably as a result of information from his family. It appears that they did not know of his transfer to the Buckinghamshire Battalion:

Wallasey casualties

Private Reginald Bawden, 5 York Road, Poulton, belonging to the King's, Liverpool Regiment, died in action on August 16th. He was formerly in the employ of the Liverpool Corn Exchange.

News reached Dartmouth a little later, where his aunt, Bessie's sister Sarah Ann, placed an announcement in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 28th September 1917:

Bawden - August 16th, killed in action in France, Private Reg Bawden, King's Liverpool Regt, beloved nephew of Mrs W Knapman, jun, Stoke Fleming, aged 20 years.

(In fact, Reginald had died in Belgium - the precise location of his death was probably unknown to his aunt).

The Army Soldiers Effects Register shows that Reginald's pay and gratuities were divided amongst all his surviving brothers and sisters; Harry's was sent at his request to the British Red Cross Society.

Commemoration

Reginald is commemorated on the War Memorial at the Victoria Central Community Hospital in Wallasey, which is an engraved brass frame holding parchments listing those who lost their lives in the Great War.

The War Memorial on the promenade in Wallasey shows no names, but inside is a casket containing a Book of Remembrance with the names of the fallen.

His name does not appear on memorials in Dartmouth.

Sources

Coastguard Establishment books and registers are free to download from the National Archives, reference ADM 175. Those consulted for Isaac Bawden (shown as Bowden) were:

- ADM 175/19 Ireland 1845-62

- ADM 175/20 Ireland 1862-1866

- ADM 175/10 England Part III (Dover to Salcombe) 1862-1866

See also the National Archives Research Guide on Coastguard Officers

Other information sourced from Coastguards of Yesteryear website

Liverpool Female Orphan Asylum

Ripley Hospital School, now Riply St Thomas Church of England Academy

Ripley Hospital School admission register on subscription website

Toxteth Park Cemetery Inscriptions

Battalion War Diaries are availabe from the National Archives, fee payable for download. References:

- 2/1st Bucks Battalion September 1915 - February 1918 WO 95/3066/2

- 6th Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry July 1915 - January 1918 WO 95/2120/2

Diary of 2nd Lieutenant H Willes accessed on Lightbobs website, dedicated to the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

The Story of the 2/4th Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, by Captain G K Rose, MC, publ 1920 Blackwell, Oxford accessed online at archive.org

Renumbering the TF Infantry in 1917

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Bawden |

| Forenames: | Reginald Pritchard |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 267176 |

| Military Unit: | 2nd/1st Bn Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry |

| Date of Death: | 16 Aug 1917 |

| Age at Death: | 19 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Third Battle of Ypres |

| Place of Death: | Langemarck |

| Place of Burial: | Buried Cement House Cemetery, Langemark, Belgium |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | No |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | No |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Dartmouth Chronicle Obituary |