William Henry Wellington

William Henry Wellington was born in Kingswear on 28th July 1896. He was the second son of Henry Wellington and his wife Susan Anne Uren. He spent much of his early life migrating between Kingswear and Dartmouth.

Henry Wellington was born in East Allington but came to Dartmouth with his family some time before the 1881 Census, where they were recorded living in Oxford Slip. Aged 13, Henry was already at work as a domestic servant. By 1889, he was working as a labourer, and living in Kingswear. On 23rd February 1889 he married Jane Court, the daughter of Edward Court, a bootmaker, at St Thomas of Canterbury, Kingswear; their daughter Jane was born in 1890. In the 1891 Census, the family was recorded at 2 Summerland Terrace, Kingswear, and Henry continued to work as a labourer. But tragedy struck the small family when Henry's wife Jane died in 1892, followed by their daughter Jane (or Jenny), aged 3, in 1893.

On 20th June 1894, Henry married for the second time at St Thomas of Canterbury in Kingswear. His second wife was Susan Anne Uren, daughter of Simon Uren and his wife Agnes Justham. Susan was born in Milton, in Buckland, north of Plymouth. She attended Mary Tavy School, where the register shows her (and also other members of her family) attending between 11th April 1881 and September 1884. She had previously attended school in Buckland. In the 1891 Census, she was recorded as a general domestic servant in Tavistock, in the house of Susan Crocker, and her family. How Henry and Susan Anne met is not known.

Henry and Susan Anne made their home in Kingswear. Their first child, Albert Henry, was born in 1895 (according to birth registration records) and William followed a little over a year later. On 6th January 1898, Albert was sent to school in Kingswear, and the family were recorded living at Boohay, near Kingswear. He stayed only six months, however, leaving because the family moved from Kingswear to Dartmouth. Agnes Gladys was born in Dartmouth towards the end of 1900 and in the 1901 Census, the family were recorded living in Crowthers Hill. Henry was working "on his own account" as a Stone Quarryman.

Frederick was added to the family in Dartmouth in 1901, but the following year the family was once again on the move back to Kingswear. Albert and William were both admitted to Kingswear school on 27th October 1902. The family's address was first shown as Nethway (presumably Nethway Farm, near Kingswear) and subsequently as Hillside Terrace. Both boys had previously attended school in Dartmouth. But again the family did not stay long. On 22nd May 1903 they left Kingswear school, to return to Dartmouth. Soon, another baby was on the way, and was born shortly after the return to Dartmouth, in 1904. The little girl was named Jenny (perhaps in memory of Henry's first daughter, who had died). She was followed by Doris (1907), Sidney (1909) and Edward (1910).

Henry and Susan took their whole family to be baptized at St Saviour on 29th March 1906. Henry was working as a labourer in Dartmouth and the family lived in Clarence St at that time. Shortly after Edward's birth, however, the family once again moved back to Kingswear, where Henry obtained work as an agricultural labourer. At the 1911 Census the family was living at Brownstone, near Kingswear. William too had begun his working life in agriculture, as a shepherd. Albert, in the meantime, must have blotted his copybook, because the 1911 Census recorded him at the Devon & Exeter Boys Industrial School, a young offenders' institution.

In 1913, both Albert and William decided to join the Royal Navy. Both seem to have overstated their age. William signed on for a twelve year engagement as a Stoker II on 4th November and Albert did likewise shortly afterwards, on 11th December. William's naval record says that he was 5' 7" tall, with brown hair, hazel eyes, and a "dark" complexion (perhaps from his life outside with the sheep). His brother Albert was half an inch taller, with light brown hair, blue eyes, and a "fresh" complexion. He had been working as a labourer in a ship yard, after leaving the Industrial School.

Service

William and Albert both began their training at Devonport. William, having started a month earlier than his older brother, was posted first, and afterwards the brothers' paths diverged completely. On 18th April 1914, William was posted to HMS Gibraltar, an old Edgar class cruiser launched in 1892, and by 1913 used as a training ship. On 18th April 1914, the day he joined her, according to his naval record, she was in Devonport, where she remained for a month. On 17th May 1914 she arrived at Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland. According to her log, she was involved in some gun laying practice and on 3rd June fired a royal salute of 21 guns for King George V's birthday. On 13th July she left for Pembroke, in Wales, where another group of boys under training joined her from Devonport. On 17th July she departed en route to Spithead, off Portsmouth, for the Naval Review of that summer. Three days later, she "proceeded for the Combined Fleets passing the Royal Yacht in two lines" and at 11.20am, the ship's company "cheered ship in honour of HM the King".

HMS Gibraltar then headed back to Queenstown, by way of Plymouth, where she "discharged mobilising party". She arrived at Queenstown on 24th July but did not stay long. On 29th July she left for Devonport, where she arrived on 31st July. The following day, she "discharged 61 boys and 19 Stokers 2c to Royal Naval Base" - one of them was William.

He may perhaps have had the opportunity for some time at home before his war began. On 22nd August, his naval record shows that he was appointed not to sea, but to the Naval Camp at Deal. William was thus involved right from the very start in what became the Royal Naval Division.

The Royal Naval Division

The Royal Naval Division originated in plans made before the war for an "Advanced Base Force" - a force of Royal Marines operating under the direction of the Admiralty to seize, fortify, or protect any temporary Naval Bases established during a conflict to sustain the Fleet or provision an army in the field. The force was to consist of a Royal Marine Brigade of four infantry battalions and one from the Royal Marine Artillery.

At the outbreak of war therefore this Brigade was duly formed. On 16th August 1914, the Admiralty (led at that time by Winston Churchill) decided to increase this force by adding two brigades of Naval Reservists who had reported for duty but who were, at least for the moment, surplus to the needs of the Navy. In his orders setting this up, Churchill wrote that "the first essential is to get the men drilling together in brigades; and the deficiencies of various ranks in the battalions can be filled up later".

A camping ground was selected near Deal with 160 Royal Marine tents and a further 700 tents were to be supplied from the War Office. 608 personnel, drawn from both active service and the Royal Fleet Reserve, were appointed to set up the Camp. Evidently, one of them was William. Naval reservists flooded into the Camp between 22nd-26th August.

At this time the situation in Europe was developing rapidly and at home, recruits were flooding in whom the Army was unable either to train or equip. On 3rd September 1914 it was decided to train and equip the two Brigades of Naval Reservists, with the hitherto independent Marine Brigade, as an Infantry Division.

The naval reservists were divided into two Brigades, consisting of four battalions. Although known first by numbers, very soon the battalions were given the names of eight famous admirals:

| 1st Naval Brigade | 2nd Naval Brigade |

|---|---|

| 1st Bn - Drake | 5th Bn - Nelson |

| 2nd Bn - Hawke | 6th Bn - Howe |

| 3rd Bn - Benbow | 7th Bn - Hood |

| 4th Bn - Collingwood | 8th Bn - Anson |

On 15th September, William was appointed to "C" Company in Anson Battalion, which on 9th September had moved from Deal to Betteshanger. He was in elevated company - Rupert Brooke and his friend Denis Browne reported to Betteshanger on 27th September 1914 (Brooke and Browne subsequently transferred to Hood Battalion).

The Royal Naval Division presented an unusual mix of men. In the words of Douglas Jerrold, the historian of the Division:

Those from the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, whether they had joined before the war, or were recruited after the war ... were men of no inconsiderable education, inspired by an enthusiasm which more than made up for that lack of mere physical stamina inevitable in men whose daily life is one of office routine. In sharp contrast were the newly-joined recruits taken over from the War Office, men who had enlisted in the very first days of the war ... These men, of truly remarkable physique, inexhaustible patience and unfailing courage, were almost all miners from Durham and Northumberland ... In many ways resembling these North Country recruits ... were the men of the Royal Fleet Reserve ... they never became "smart" soldiers ... they were resentful of incompetence in their officers, and they were inclined to assume it any newly joined officer till the contrary was proved ... as a body, these men were possessed of a remarkably high sense of duty ... only completely evoked under the most trying conditions.

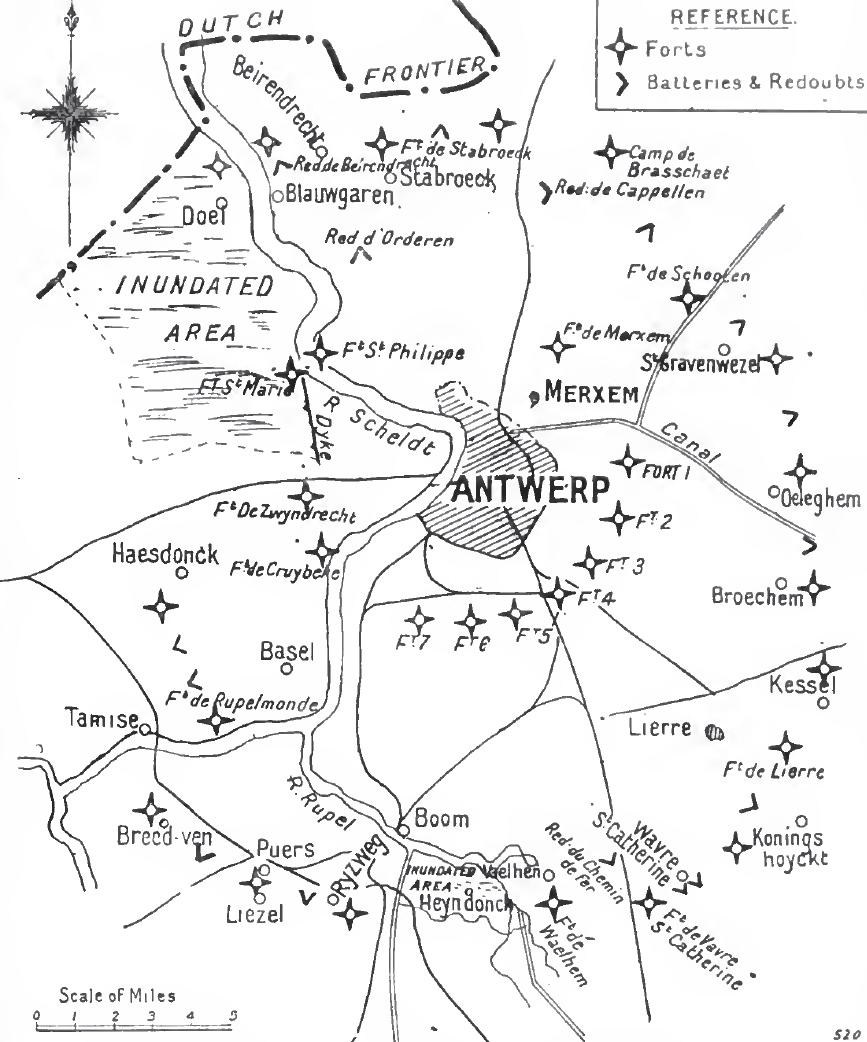

The Division had been together only a very short time, however, when on 4th October they were ordered to move overseas. Four days earlier, on 30th September, the German Army, which was attacking Antwerp, broke through the outer line of the fortifications of the city. The Belgian Government at first planned to withdraw their Field Army immediately, but, persuaded by Winston Churchill in what subsequently became a controversial flying visit to Antwerp, they decided to try to hold on for longer, with the support of British troops. The Marine Brigade of the Royal Naval Division (who were, more or less, fully trained and ready) were deployed immediately, and the two Naval Brigades followed.

Jerrold describes them as "a slender asset from a military point of view" and to add to their lack of training and experience, they had a difficult journey - the transports were overcrowded and many had to stand the whole way. Few had bandoliers or haversacks and many carried hastily issued ammunition in their pockets. On the train to Antwerp, they were ordered not to sleep in case the train was attacked.

They arrived in Antwerp on the morning of 6th October and went into the line of inner forts which covered Antwerp from the east and south, alongside Belgian forces and the fortress garrison.

The 1st RN Brigade were on the left of the line (Forts 2-5) and the 2nd RN Brigade were on the right (Forts 5-8). The night of October 6th/7th passed quietly and during 7th October they were kept occupied in attempting to strengthen the defences. The night of 7th/8th October was also largely quiet, though there were some casualties due to shelling. During the afternoon of 8th October, however, Belgian positions began to fall, the situation became untenable, and the Royal Naval Division was withdrawn. The 2nd Brigade (including Anson) and the Marine Brigade were able to reach the rendezvous at Zwyndrecht, a western suburb of Antwerp, though in extremely difficult conditions, through refugees fleeing from the city. The 1st Brigade, however, received the order to retreat later, and on receiving (incorrect) information that the railway line for which they had been heading had been cut, decided to cross the Dutch border. Some 1500 men were interned, though a small group were able to make their way along the Dutch border and escape. Meanwhile, the rearguard, which was Royal Marine (Portsmouth) battalion, together with a large group of "stragglers" from the Royal Naval battalions, had managed to reach Kemseke station. But the train they were on was derailed. On leaving the train, many were surrounded and captured, though several were able to escape. The city fell shortly after, on 10th October.

The Royal Naval Division had, in all this, suffered serious losses:

- Killed: 7 officers and 53 men

- Wounded: 3 officers and 135 men

- Interned: 37 officers and 1442 men

- Captured: 5 officers and 931 men

William's Royal Naval Division service record confirms that he served in Belgium during 1914.

The work to rebuild and train the Division started again on the return to England. The three Battalions that had been lost to internment were re-formed. A supply depot was established at Crystal Palace and a training school set up. The nine Battalions that had survived the Antwerp expedition were overhauled and many changes were made in command personnel. Divisional troops, such as engineers and medics, were recruited and trained, and a divisional training camp organised at Blandford. Meantime, Anson Battalion returned to the summer camp at Bettyshanger and then in November went into barracks at Chatham.

The Division was still under training when orders were received to move to an unknown destination. Two Royal Marine Battalions went first and the rest left for Avonmouth on 28th February 1915. The Royal Marine Battalions were to provide support to the Fleet in the destruction of the Dardanelles forts; at the time the Royal Naval Division left England, their intended purpose was as part of the military concentration of troops required to follow up what was expected to be a Naval success in forcing the Straits.

The Division arrived in Mudros during the second week in March and on 18th March 1915 arrived off the eastern shore of the Gallipoli peninsula. However, their first sight of this fatal land was an anticlimax. The naval attack had failed and the Division was ordered to return to Lemnos. From there they were sent to Egypt, to await the rest of the troops being brought together for the military operations. For more detail on the build up to the landings, please see our Gallipoli timeline.

The Landings on Gallipoli

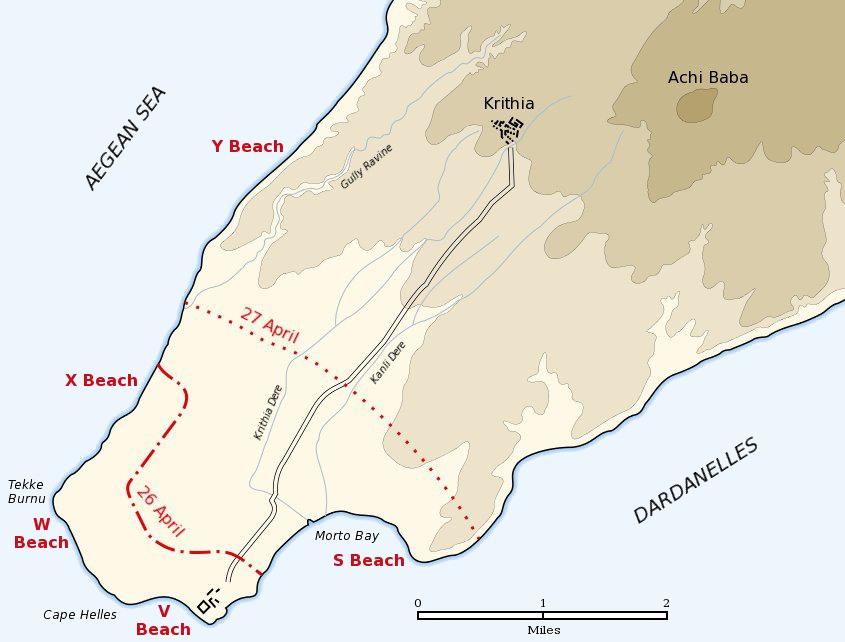

The majority of the Royal Naval Division was involved in a diversionary attack at Bulair, but Plymouth and Anson Battalions were attached to the forces involved in the main landing at Cape Helles.

The two Battalions were spread amongst the southern landing sites as follows:

- V beach: A Company Anson, 1 Platoon D Company Anson

- W beach: B Company, Anson, and Anson Battalion HQ

- X beach: C Company and D Company Anson (less the platoon landing on V beach)

- Y beach: Plymouth Battalion RMLI

As a member of C Company, William presumably found himself attacking X beach. He was, relatively speaking, fortunate. The landing site was lightly defended and the covering fire from HMS Implacable was effective. By 6.30 am the landing party had reached the shore and had climbed to the top of the cliffs without a casualty. The remainder of the troops and equipment had arrived by 7.30am. As they pushed inland, however, they met Ottoman forces moving towards W beach. The officer commanding the forces at X beach, Lt Col Newenham, secured his left and front and on his right, attacked "Hill 114", lying between X and W beach, and reached the top by 11.00am.

The main landings at V and W beaches had suffered very heavy casualties. Nevertheless, a foothold was secured on W beach and the landing of the main body was accordingly diverted from V beach to W beach. But the costs of achieving this had been so great that it was decided not to attempt to advance further, and instead to consolidate the fragile landing position. French forces arrived from their diversionary attack at Kum Kale to strengthen the allied line on the right; and Ottoman forces meanwhile retired to a strong defensive position at Krithia, awaiting reinforcements. Allied forces were therefore able to advance approximately two miles inland by 27th April.

On the night of 1st/2nd May Ottoman forces counter-attacked. Anson Battalion was sent to support the French on the extreme right of the allied line, and stayed there for 3rd and 4th May, "doing much to restore the confidence of the French native troops, who had not as yet got acclimatised to the strange conditions" (according to Jerrold). The counter-attack was defeated and Ottoman forces once again applied themselves to strengthening the defences of their Krithia line.

On 5th May Anson was withdrawn from the front line, but respite was brief, for a further attack on Krithia was ordered on 6th May. Again Anson, this time with Hood, was deployed on the left of the French position, and had some success, reporting an advance of 600 yards. Elsewhere little progress was made and so Hood and Anson were ordered not to advance further. There was little success anywhere on either of the two following days. However, an Ottoman counter-attack on 10th May was successfully resisted. Jerrold comments, ruefully: "As ever the allied armies were as irresistible in the face of defeat as they were ineffective in the organisation of victory".

On 12th May the Naval Battalions withdrew to bivouacs southwest of Achi Baba and were rejoined by those Battalions which had been sent to support the Anzac landings. The campaign entered the phase of trench warfare - the Naval Division remained on the French left, responsible for a stretch of front between the Achi Baba nullah and the Krithia nullah. However, it was a feature of Gallipoli that there was no area behind the line which was free from fire, and "rest" areas provided neither comfort nor safety. As the heat of the summer grew, and the dead multiplied, the conditions were dreadful.

A new attack was planned for 4th June, across the British front. Howe, Hood and Anson Battalions were to attack the two front-line trenches immediately opposite them, with support from three companies of the recently arrived Collingwood Battalion. A prior bombardment was ineffective; but nonetheless, at 12 noon the attack began. Severe casualties were sustained, and the attack failed. To the right, the French had also failed; though in the centre of the British line, three lines of Ottoman trenches had been captured and held. But as no progress had been made on the right of the line, the position was not held.

In what Jerrold calls "this disastrous engagement", more than 60 officers and 1300 men of the Royal Naval Division were casualties, and of these, nearly half were killed. The Division had to be restructured - Hood, Howe and Anson Battalions absorbed the officers and men of Collingwood and Benbow, and the Naval Brigades were reduced to three Battalions each.

Following the failure of the third attempt to take Krithia, the campaign south of Achi Baba once again settled into the routine of continuous trench warfare. The Naval Division remained in their position to the left of the French; the 1st Brigade and the Marine Brigade took over the line alternately, and the 2nd Brigade (including Anson) were taken to Imbros for a (much-needed) rest.

Most of what remained of the Naval Division was once more thrown into an attack planned for 12th July, though Anson was not involved, having been detached to be trained in pack mule work. William was thus spared the final fighting challenge thrown at the Division as a whole. In the attack, the Division was able to achieve some advances, and improve the position of the sector of the line for which it was responsible. But this was once again at very heavy cost. After the battles of June, the strength of the Division had been 208 officers and 7141 other ranks. On 1st August, it was shown as 129 officers and 5088 men. Further, the conditions in which they had been forced to exist were appalling, and this badly affected the health of many men. It is highly likely that the disease which eventually caused William's death had already developed by this stage.

The withdrawal at this point of 300 Fleet Reserve Stokers, for fleet service, also had a severe impact on the Division. When they left, the 2nd Naval Brigade ceased to exist. The Marines also had no adequate reinforcements, and the casualties they had sustained meant that their four Battalions were amalgamated into two. With them were brigaded Anson (still on detached duty) and Howe Battalions.

The Division as a whole was too weak to be involved in any subsequent significant engagement, but Anson continued detached for special duty in support of the landings at Suvla Bay in early August, providing pack transport with their mules. The attack at Suvla failed to break the deadlock, and the campaign was at a standstill. As Jerold puts it: "During the September and October, the war-weary divisions at Cape Helles melted like snow in the noon-day sun". One of those finally to succumb to the terrible conditions on the peninsula was William.

Death

On 14th September 1915, he was admitted to the 3rd Field Ambulance Station, Royal Naval Division, with "debility and cardiac enteritis", according to the record (this must surely have been "cardiac debility and enteritis")

That day he was evacuated from Gallipoli to Mudros, and transferred to No 1 Australian Stationary Hospital, Mudros, with "diarrhoea". He remained in Mudros for five weeks, being invalided home to England on the Hospital Ship Aquitania, still with "diarrhoea", on 21st October 1915. He was taken to the Royal Naval Hospital at Portland, where he remained for over three months. Henry and Susan were able to visit him there. Gallipoli finally claimed yet another casualty at 1.30 am on the morning of 5th February 1916.

The Dartmouth Chronicle of 18th February 1916 reported his death as follows:

Dartmouth Naval Stokers Death After Service at the Dardanelles

We regret to have to record the death of a young Dartmouth naval stoker, William Henry Wellington, of the Royal Naval Division, son of Mr and Mrs Wellington, Higher St. Deceased, who was only twenty one years of age joined the Navy two or three years ago, and not only did he display much efficiency in the discharge of his duties, but he was very popular with his comrades. Whilst at the Dardanelles he was unfortunately taken ill with dysentery. On his arrival in England he was taken to the Royal Naval Hospital Portland, where he was seen by his parents, and everything possible was done for him, but unfortunately his disease proved fatal.

The announcement of his death was conveyed to his mother in the following letter from the Record Office, Royal Naval Division, dated Feb 5th, 1916:

I deeply regret that a telegram from the Royal Naval Hospital Portland has been received here today announcing the death of your son Stoker William Henry Wellington, DEv K 21848 RN late of the Anson Battalion, 2nd RN Brigade, RN Division, on 5th February 1916, at 1.30am, from dysentery. Any further information that may be received shall be made known to you at once.

The funeral took place at Portland with full naval honours, and was attended by a firing party from deceased's own Battalion. There were several beautiful wreaths. Mr and Mrs Wellington, whose eldest son is also in the Navy, were both present.

In fact, William was not yet twenty years of age.

Commemoration

William is buried in the Royal Naval Cemetery at Portland where he is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

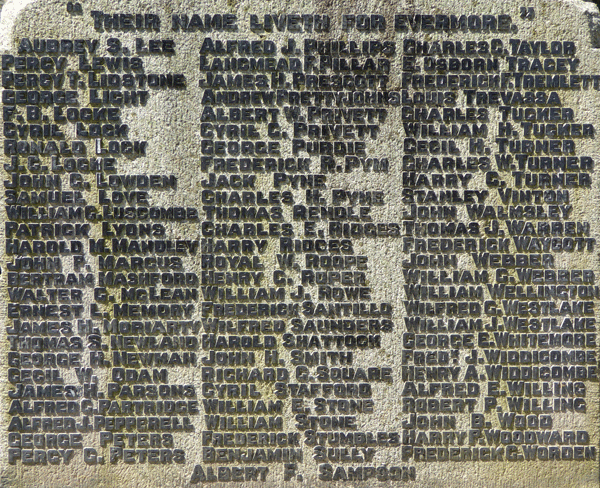

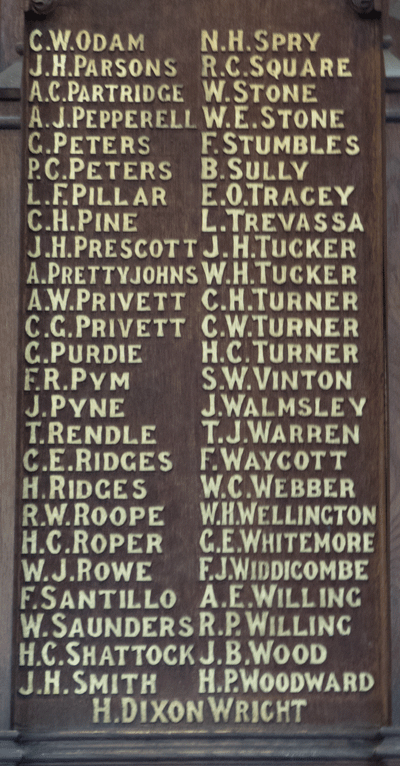

He is commemorated in Dartmouth on the War Memorial in St Saviour's Church, where he was baptised 10 years before he died, and on the Dartmouth Town War Memorial.

Records indicate that his mother and father had moved back to Dartmouth at the end of the war, but later moved once again to Kingswear.

William's brother Albert served with the Royal Navy throughout the war and beyond.

Sources

Naval Service Record for William Henry Wellington is downloadable from The National Archives, fee chargeable, reference ADM 339/2/4980

Naval Service Record for Albert Henry Wellington is downloadable from The National Archives, fee chargeable, reference ADM 188/910/21517

The Royal Naval Division, Douglas Jerrold, Naval & Military Press reprint

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Wellington |

| Forenames: | William Henry |

| Rank: | Stoker 2nd Class RN |

| Service Number: | K/21248 |

| Military Unit: | C Company, Anson Battalion, Royal Naval Division |

| Date of Death: | 05 Feb 1916 |

| Age at Death: | 19 |

| Cause of Death: | Disease: dysentery |

| Action Resulting in Death: | |

| Place of Death: | Royal Naval Hospital Portland |

| Place of Burial: | Royal Naval Cemetery, Portland |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |