Charles Gerald Taylor

Charles Gerald Taylor was not a native of Dartmouth or Devon, but came to the town because of his naval career. As a young man he was a distinguished athlete and rugby international; in later life he became a distinguished naval engineer.

Photograph kindly provided by Charles' grandson, John Taylor.

Family

Charles was born in Ruabon, Wales, on 8th May 1863, though not to a Welsh family. His father, Alfred Lee Taylor, was born in Rochdale, Lancashire, a younger son of William Taylor, a solicitor, and his wife Mary Fetzer. Alfred was admitted to Corpus Christi College Cambridge in 1845 as a "sizar". (This originally meant that lower fees were paid in return for acting as a servant to fellow students, but by the mid 19thC sizarships were in effect a sort of scholarship, awarded on the basis of an examination). After graduating BA in 1849 he became a schoolmaster in Carnarvon, and in January 1854 (having taken his MA the year before) he married Annie Bevington. Annie was the third daughter of Alfred Bevington of Bermondsey, from a prosperous London Quaker family, and owner of a glue factory.

Alfred and Annie first made their home in Carnarvon, and their first son, Richard, was baptised there in January 1856. However, in 1855, Alfred was appointed as the schoolmaster at Ruabon Boys Grammar School. This was a charitable foundation providing free education for the poor of Ruabon established originally in 1618. The school had recently been reconstituted with new trustees following criticism of it in a government report of 1847 into the state of education in Wales (the report became infamous due to its observations on the influence of the Welsh language and of religious nonconformity on standards of education). The services of the previous headmaster were dispensed with, Alfred was appointed, and the school was moved to a new site in new buildings and facilities, including accommodation for the headmaster. All Alfred and Annie's six subsequent children, including Charles Gerald, were born and brought up in Ruabon.

Shortly after his appointment to the school, Alfred Lee Taylor was ordained deacon in 1856 and priest in 1857. In 1875 he became the chaplain to Bersham Church, the private chapel on the Plas Power estate, built by the FitzHugh family in that year; and between 1883 and 1903 he was also curate to the Vicar of Wrexham. Meanwhile he remained the headmaster of Ruabon School until his death in 1903. During his time in the post, the school continued to grow and develop, with more new buildings opened in 1896.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Charles Gerald was educated at Ruabon. In 1877, during the time he was at school there, the Wrexham Advertiser reported speeches at prize giving saying that there were at that point 105 boys in all, 20 of whom were boarders. An inspection reported on the same occasion had shown good standards in Greek, Latin, English, French, Mathematics and also in Freehand and Mechanical Drawing. Charles was one of the prize-winners, receiving "Lives of the Stephensons" by Samuel Smiles, chosen, like all the prizes, by his father. Presumably the book either stimulated, or reflected, an interest in engineering. He was also developing as a sportsman, representing the Grammar School several times at cricket, and also competing in the championship race of the Wrexham Bicycle Club. He was also a gifted player of association football.

Evidently Charles decided to become an engineer and to do so by joining the Royal Navy. There do not seem to be any obvious prior family connections with the service - his choice is therefore interesting, as naval engineering was at that time faced with many challenges. During his career, Charles was to become centrally involved in the continuing changes affecting the naval engineering service.

Engineering in the Royal Navy

The change from sail to steam in the Royal Navy during the nineteenth century meant an increasing need for engineers to look after the engines; and as the number of engineers grew, so, slowly, did the arrangements for their training develop and change. When the very first steam ships appeared in the Navy, in the mid-1820s, engineers had first been recruited informally and employed on a local basis without uniform or rank. They were usually older and experienced men who had held responsible positions and had certain expectations about how they should be treated. However, to begin with, they were not granted commissioned status, were required to mess separately, not allowed the use of cabins, and, due to the manual nature of their work, considered socially inferior.

Not surprisingly this state of affairs failed to attract the most talented individuals. By 1846 the Royal Navy had to admit "great difficulty in inducing competent engineers to enter", at a time when steam power was becoming an integral part of warship design. Notwithstanding considerable opposition from those both within the Navy itself and elsewhere, who considered that engineers were not "gentlemen", the Navy in 1847 awarded the most senior engineers commissioned status and improved pay, rank, status and uniform, emphasising the equivalence between the "executive" and the "engineering" branch.

Training of future naval engineers still lagged behind, however. The assumption was that junior engineers would come from the dockyards or would enter the Service already trained. In 1842 the Navy had begun to develop a more formal system of training within the dockyards. Schools for young apprentices, including Engineers' Boys, were established at Woolwich, Sheerness, Portsmouth and Devonport, with external supervision, and soon developed a sound reputation. In 1863, Engineers' Boys were renamed Engineer Students. They were to enter at age 15, twice yearly, by examination. They then spent six years in Dockyard factories, including two evenings per week at Dockyard school. They would then enter the Navy if they passed a final examination.

However, although a limited number of outstanding scholars were selected for higher training, the scheme was not envisaged as a source of engineer officers. A small number of naval engineer officers came from the Royal School of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, established in 1864 in South Kensington, and then amalgamated with the new Royal Naval College at Greenwich in 1873. But the majority of engineering staff were still recruited locally, trained in dockyards, and lived in lodgings ashore. There were thus social divisions not just between the engineers and the executive branch, but within the engineers themselves. Further, the introduction in 1868 of the new class of engineering rating, to be known as Engine Room Artificers, who were qualified as engine fitters, boiler makers or smiths, also increased the need for the role of the engineer officer to focus more on professional supervision and less on "hands-on" functions.

These issues prompted a review under Admiral Sir Astley Cooper Key, which reported in 1876. Most of his Committee's report dealt with issues of pay, rank, promotion and retirement of the various engineer classes serving in the Fleet. The report also recommended the end of separate messes, cabin accommodation for senior engineers, and, most far-reaching, that engineers should cease to be "civil" officers and instead be incorporated within the "military" branch, though without any prospect of actually commanding a ship. Though this was broadly accepted, these changes took many years to come into effect.

The Committee also considered engineering recruitment and training. As they saw it, parity between engineers and executive officers could not be achieved unless those becoming engineering officers were "of the right class of society" - and those of the "right class" were deterred from entering the Navy by "indiscriminate admission of lads from the lower ranks of society".

They accordingly recommended more enquiry into the background of applicants, the payment of fees by parents to help cover the costs of training, and a similar sort of approach to the naval cadet entry system: candidates to be aged between 14 and 16, entry examination to be administered by the Civil Service Commissioners, and a competence in arithmetic, algebra, geometry, geography, English and French. However, the practical training would continue in the dockyards as before, under close supervision. On satisfactory completion of the practical training, candidates would be appointed as Acting Assistant Engineers, and then go on to the Royal Naval College Greenwich to pursue theoretical studies.

They also recommended that engineer students should be provided with a dedicated residence, both to assist with finding accommodation and to help to accustom them to naval practice and discipline. Though actual instruction would continue in the Dockyards, this recommendation in effect provided for engineer students a similar facility to that which HMS Britannia provided for naval cadets. The vessel chosen, HMS Marlborough, was an old first rate 121 gun sailing ship converted to steam. She had served from 1858-1864 as flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet but since then had been laid up. The first students boarded her in Portsmouth in December 1877.

HMS Marlborough was followed three years later by another such establishment at Keyham, next door to Devonport dockyard, this time in buildings ashore. The aim seems to have been to split the annual entry into two and operate two parallel establishments. At that time, neither were educational establishments as such - study took place either in the yards or in the dockyard schools.

Given his social and educational background, Charles must have seemed to the engineering recruiters certainly to be someone from "the right class of society". His father's school would have equipped him to pass the entry examination without too much difficulty. He joined HMS Marlborough in Portsmouth two years after she opened, in 1879, aged 16, as an Engineer Student. His apprenticeship training lasted six years, until 1885. Evidently he did well enough to be accepted into the Royal Navy on 1st July 1885 as an Acting Assistant Engineer. He then was selected for a year's further higher-level study at the Royal Naval College Greenwich, and on completion of this was commissioned as an Assistant Engineer on 1st July 1886 (equating to Sub-Lieutenant).

Rugby and Athletics

Charles first encountered rugby during his time at HMS Marlborough. The game of rugby had only fairly recently been codified and standardised through the formation of the English Rugby Football Union in 1871. The Scottish Rugby Union followed in 1873, the Irish in 1879 and the Welsh in 1880. At HMS Marlborough, the preferred sport was rugby rather than football, and Charles was converted into a three-quarter. He was a natural for the game and soon became a key member of the team.

The Hampshire Telegraph of 24th January 1880 (only a few months after he joined) recorded Charles as a forward in a winning match played by HMS Marlborough against Ryde Club, and again on Saturday 13 March 1880, as a member of HMS Marlborough (2nd 15) against the 2nd 15 of The Royal Academy Gosport (a "crammer" catering for those wishing to join the naval, military and diplomatic services). On that occasion, "C G Taylor, seizing an opportunity, made a very neat drop kick between the posts, thus placing the first goal to the credit of the Marlboroughs".

In the summer, his undoubted sporting talent led him to cricket, athletics, and swimming. In 1882, for example, he played many times for HMS Marlborough at cricket, and in the HMS Marlborough Students Athletic Sports of that year he won the long jump, with a jump of 10 feet; tied first in the high jump, at 4 ft 11ins; came second in the two miles bicycle race; and also won "a slow bicycle race of 100 yards, which excited great amusement, each competitor being dressed in an eccentric costume". Charles appeared as a "Christy minstrel". Previously he had also won first prize in the swimming tournament for swimming the longest distance underwater.

In 1883 he competed for HMS Marlborough at the annual event of the Fareham Amateur Athletics Club and won the pole vault, with a height of 9ft 8ins, subsequently clearing 10ft 2ins for exhibition. This became his speciality - in 1884 he competed in the pole vault at the national Amateur Athletic Championship in Birmingham and came second, with 10ft 4ins, 4ins below the winner. A few months later, at the annual Naval and Military Athletic Meeting in Portsmouth, he cleared 10ft 9ins.

His rugby career, meantime, continued to develop. In December of 1883 he played rugby at county level for Hampshire, in a match against Devon, playing this time as a three-quarter; we can infer from this, and from his prowess as a long jumper and pole vaulter, that he was a fast sprinter. He came to the notice of the Welsh selectors, and during that season he was selected to play for a scratch Welsh team against Oxford University. He scored the only two tries obtained against the very strong Oxford team, and shortly afterwards was chosen for Wales. He made his debut for Wales on the wing against England at Leeds in the 1884/5 season and put in some wonderful flying kicks. A drop goal nearly brought off a great victory, but was disallowed. He played in both the subsequent games against Scotland and Ireland; and also continued to play for Hampshire and for HMS Marlborough, captaining the team in his final months of his training there in 1885.

Charles became an automatic choice for Wales over four seasons, winning nine caps in all, and missing only one through injury. Against Scotland, in a match played at Cardiff, he "brought off a grand run to the middle of the field right through the thick of his antagonists" and "all but scored". In 1885, after his move to London to attend RNC Greenwich, he was able to join one of the best club teams in the country, at Blackheath. As a Welsh "exile", he was one of the founder members of London Welsh Rugby Club, though did not play for them frequently.

When commissioned into the Royal Navy on 1st July 1886, he was first appointed to Chatham Dockyard. Perhaps this was fortuitous, or perhaps the naval authorities were happy to facilitate his international rugby career a little longer. He continued to play for Blackheath and London Welsh. In 1887 he played again for Wales, against England and Ireland. The latter was his final international game, and was a win for Wales. But his next appointment, to the Mediterranean Fleet in the summer of 1887, necessarily ended his rugby-playing career. Nonetheless his reputation remained considerable: an article in the Western Mail of 7th January 1895, seven years after his last matches, described him as "the sheet anchor of the Welsh committee for many a season".

Charles' Naval Service

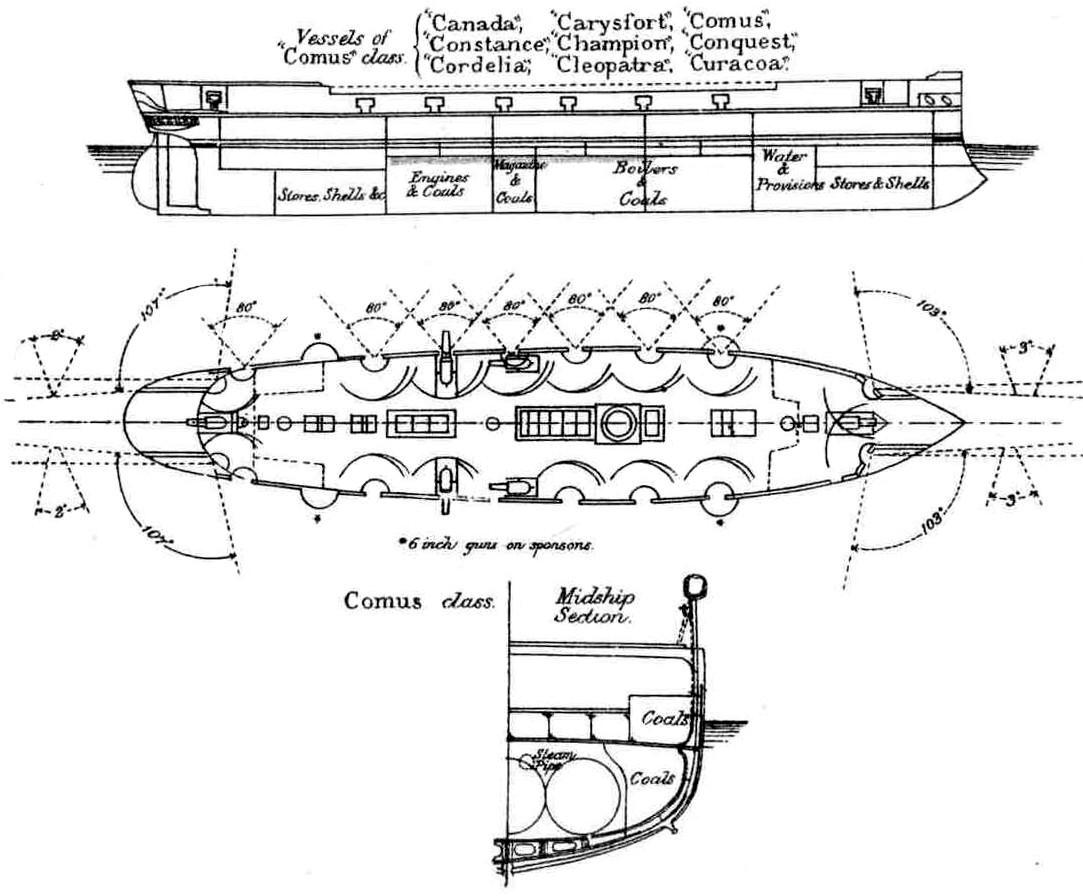

Charles joined HMS Thalia on 17th May 1887 for his journey out to the Mediterranean, where he was appointed to HMS Carysfort as an Assistant Engineer on 9th June 1887. Carysfort was a Comus-class corvette completed in 1880, perfectly illustrating the so-called "transition period" of the late Victorian Navy. She had both an extensive sailing rig and a steam engine; she was made of both wood and metal, with a metal hull encased in timber, extending to the upper deck; and she carried her large guns very much as old sailing ships had done.

According to Charles' naval service record, during his time in Carysfort he was also attached for around six weeks to Torpedo Boat 22. Torpedo Boats were a fairly recent addition to the Navy's small ships - the first British Torpedo Boat (No 1) was built in 1877. No 22 was built in 1884-5 as a "first class" torpedo boat - of sufficient size to operate offensively and independently inshore, patrolling coastal waters for limited periods beyond her supporting port or tender ship.

Charles must have been due for a move when on 29th April 1890 he was admitted to hospital with malaria. Evidently he was quite seriously ill because in June he was invalided home on leave and put on half pay on 27th August. On 1st September, however, he was promoted to the rank of Engineer - though still on half pay. He was not found fit for active service until the end of September.

He was next appointed in October 1890 to HMS Gossamer, a "Sharpshooter" class torpedo gunboat, then being completed at Sheerness Dockyard. Torpedo gunboats were designed to screen battle fleets from attacks by torpedo boats, but proved not to have sufficient speed, and were rapidly superseded by "torpedo boat destroyers" (see below). Charles' time in the UK ended in early 1891, with three weeks allocated to HMS Wildfire, at that time the Flagship to Commander in Chief The Nore, perhaps for some specialised duty.

On 10th February 1891 he boarded HMS Tamar, a troopship, to travel to China to join HMS Imperieuse, then serving as the flagship of the China Station, based then at Singapore and Hong Kong.

HMS Imperieuse was an armoured cruiser completed in 1886. She was originally fitted with a sailing rig to help economise on fuel, but after trials, the masts and yards were removed and replaced by a single pole mast between the funnels. Armoured cruisers attempted to combine the protective virtues of armour cladding, with capability for long range and speed. Imperieuse represented a compromise between protection and speed, involving armoured protection covering roughly half of the length of the ship in the middle of each side, with the boilers and engines positioned behind it, and the coal stored in bunkers at either end.

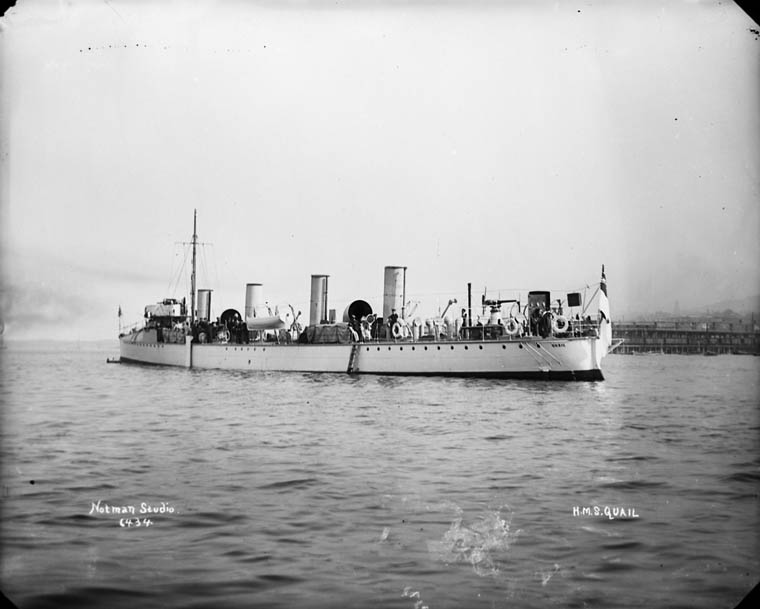

Charles spent three years on the China Station, returning to England in HMS St George. After a period of leave spent at Ruabon, during which the Cheshire Observer reported him winning a prize at Wrexham Dog Show, he was next appointed to HMS Banshee on 20th October 1894. HMS Banshee was a torpedo boat destroyer, then under construction at Laird's, in Birkenhead - she was launched on 17th November 1894. A little under a year later, on 28th September 1895, he was transferred to HMS Quail, another torpedo boat destroyer built by Laird's, which had been launched at Birkenhead four days earlier.

Torpedo boat destroyers, or simply destroyers, as they came to be known, were the next stage in the mini-arms race provoked by the development of the torpedo. Their key characteristic was speed - they were intended to be faster than torpedo gunboats, and thus able to keep up with their fleets and with the opposing torpedo boats. HMS Quail was one of four destroyers ordered from Lairds in 1894-5. Her detailed design was left to the builder, provided she met a required speed of 30 knots - consequently, the class became known as "the 30 knotters". Trials conducted in December 1896 showed that she could indeed achieve this and she was commissioned in June 1897. The journal "The Engineer" commented, in its 1st January 1897 issue, that: "the construction of torpedo boats and torpedo boat destroyers goes on apace. Anything that is asked for in the way of speed seems to be provided. Probably the most noteworthy high speed work of the year has been done by Messrs Laird of Birkenhead". As the Engineer responsible for the destroyer's machinery, Charles must have played a key role in working with Lairds to achieve this performance.

Marriage

Charles' time in Birkenhead was not only taken up with HMS Banshee and HMS Quail. On 9th September 1896 he married Mary Cardwell, always known as "Minnie", at St Johns Church, Whittle le Woods, near Preston, Lancashire. Mary was the second daughter of James Bryham Cardwell and his wife Mary Coward Birch. James was the joint owner of the Crown Brewery at Whittle Springs, which used spring water discovered in 1845 in the manufacture of beer and soft drinks. The brewery, coupled with a hotel, had become extremely successful, and James had become a wealthy man.

Charles met Minnie because she and his sister Lillian were friends at boarding school. The couple were married by Charles' cousin, Robert Fetzer Taylor, Vicar of Gomersal, who was the son of Alfred's eldest brother, Robert Fetzer Taylor senior. Alfred assisted in the fully choral service. The dresses were described in loving detail in the Wrexham Advertiser of 13th September 1896:

The bride, who was given away by her father, was attired in white duchesse satin trimmed with chiffon and trails of orange blossoms, and her tulle veil was fastened with sprays of real orange blossoms and white heather. She carried a choice shower bouquet of roses and white heather, and wore a diamond and pearl bracelet, both the gift of the bridegroom. The four bridesmaids ... were Miss [Bessie] Cardwell, Miss Edith and Miss Lillian Cardwell, sisters of the bride, and Miss Lillian Taylor, sister of the bridegroom. They wore pale blue glace silk dresses, with white chiffon fichus, and black velvet picture hats, and carried bouquets of red carnations tied with red, white and blue ribbons, the naval colours, and wore gold signet rings, both the gifts of the bridegroom. The bridegroom, who was in uniform, was attended by his brother, Mr Guy Taylor, as best man.

After the ceremony a reception was held at Clayton Green, the residence of the bride's parents, which was attended by a large gathering of relatives and friends ... Later in the day the bride and bridegroom left amid showers of rice and slippers for Scotland, where the honeymoon will be spent ...

A (long) list of the principal wedding presents followed - china, glass, linen, and a great deal of silver.

Charles' Naval Service (continued)

Charles and Minnie first seem to have settled in Southport, as their eldest daughter, Mary Kathleen, always called Molly, was born there in 1898. However, by the time she was born, her father had once again been sent overseas. HMS Quail had taken part in the naval review off Spithead on 26 June 1897, presumably with Charles on board. He was then reappointed to Quail on 10th August 1897 when she was sent to the North America and West Indies Station, based at Bermuda.

The North America and West Indies Station was at that time Admiral Sir John (Jacky) Fisher's command. Apparently Charles caught the great man's eye, perhaps because of Quail's excellent performance in her speed trials, for Fisher recommended him for the charge of the engineering department in the dockyard at Halifax, Nova Scotia. Charles took up the role in February 1898, being appointed to the rank of Chief Engineer (equivalent to a Lieutenant of over eight years service) on 30th December 1900.

Although the Halifax appointment meant he was away from Britain, this does not seem to have been any disadvantage. Rather, achievement of this appointment (and rank) appears to have represented the entrée to the senior echelons of the naval engineering service, and to wider professional recognition outside it. On 27th October 1899 he was proposed for membership of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers by Sir William White, KCB, leading naval architect and President of the Institution; and Sir John Durston, the then Chief Inspector of Machinery (the title was subsequently altered to Engineer Rear-Admiral) who subsequently became Engineer Vice Admiral (the most senior Engineer in the Navy). His three "supporters" were nearly as distinguished: John A F Aspinall, who subsequently became President of the Institution, and who would appear to have been a Liverpool connection; Arthur Tannett Walker, of the engineering firm Tannet, Walker and Co, an Admiralty contractor; and Edward Pritchard Martin, General Manager of the Dowlais Ironworks, who also subsequently became President of the Institution.

Nor did the appointment mean complete separation from his family. Minnie sailed for Canada on 28th May 1898, with their daughter Molly. The couple's next child, Philip Cardwell Taylor, was born in Halifax in 1902. Minnie and Molly also returned to England at least once during this time, for the 1901 Census recorded them in the household of Minnie's father, James Cardwell, at Pear Tree House, Clayton.

Charles and his family returned to England in March 1903. In that year, the titles of the Engineer Officer senior ranks were changed to reflect those of the executive branch more closely:

- Chief Inspector of Machinery became Engineer Rear Admiral

- Inspector of Machinery became Engineer Captain

- Fleet Engineer became Engineer Commander

- Chief Engineer became Engineer Lieutenant

But his patron, Sir Jacky Fisher, had yet more radical plans. In 1902, on becoming Second Sea Lord, Fisher proposed complete reform of the Navy's officer education (see our article "The Unjust Load"). Amongst other things, his plans involved not just parity between the two branches but a single, common, system of entry and training. Indeed, his original plan appears to have been to attempt to achieve complete interchangeability thoughout a naval career lifetime, but this was a step too far, and eventually the new scheme involved common entry followed by specialisation.

Charles, as a Fisher protégé, was to be centrally involved in the development and implementation of the new scheme of training from the start. In April 1903 he was appointed to HMS Britannia, as senior engineer officer, and came to Dartmouth for the first time. A little over a year later, he was transferred to the Royal Naval College Osborne, being promoted to Engineer Commander in December of that year. In that capacity he was also a member of the Douglas Committee, set up to consider various issues arising from the implementation of the new scheme for officers' training, and to negotiate a way through the resistance to some of Jacky Fisher's more radical ideas. He appears to have managed the politics of this with some success, as he was commended by the Admiralty for his contribution.

On 11th September 1905 he was transferred back to the new Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, where he remained until early in 1911, apart from eight months between September 1907 and April 1908 during which he went to sea in HMS Cumberland, a Monmouth class armoured cruiser in the Home Fleet, used during that year as a cadet training ship. At the College he was responsible for the engineering training of the new scheme cadets. He was also responsible for developing the workshops at Sandquay. His work in developing and carrying out the engineering instruction involved in the new scheme received an official commendation from the Admiralty. Further, as one of the cadets for whose teaching he was responsible was the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII) he was made a Member of the 4th Class of the Royal Victorian Order, which recognises distinguished personal service to the monarch (10th February 1911). A close colleague at the time, also honoured in the same way, was Reverend Henry Dixon Dixon-Wright, Chaplain at the College. He is also on our database.

During Charles' time in Dartmouth the family occupied Townstal House (now Barrington House), in Mount Boone. The house was advertised for immediate possession and occupation in the London Standard in 1905: "a freehold detached marine residence, standing in high grounds of about one acre, commanding a fine sea prospect across the harbour and town ... having a winding carriage drive to the porch entrance; it contains a lofty dining room, cheerful drawing room, conservatory, library ... on the upper floor, eight good bed and dressing rooms ... the grounds are well laid out... large tennis lawn, good kitchen gardens, detached stabling, coach house etc". Charles and Minnie's third and last child, Nancy Elizabeth, was born in Dartmouth in 1907, and baptised at St Clements Townstal on 23rd May 1907.

Minnie and her two younger children were recorded in Townstal House in the 1911 Census (Molly was away visiting her aunt, her mother's sister Edith, and her husband, in Shropshire). Charles, however, was once more at sea, having been posted from Dartmouth to HMS Superb, after a month's course of instruction in turbine machinery. Superb was a dreadnought-type battleship completed in 1909, powered by four Parsons steam turbines.

On 7th February 1912 Charles was promoted to Engineer Captain, passing over 72 of his seniors on the engineer-commanders list. From February to October 1912 he served at the Admiralty, once more working on engineer officer training (most probably in preparation for his role at Keyham, see next paragraph). He was then appointed for ten months to HMS Hercules, the flagship of the 2nd Battle Squadron, where he was employed as principal engineering officer to Admirals Sir John Jellicoe and Sir George Warrender.

On 15th August 1913 he was appointed in command of the Royal Naval College Keyham, the first Engineer Officer ever to be appointed "in Command" of any ship or shore establishment. Keyham had opened as accommodation for Engineer Students in 1880 to run in parallel with HMS Marlborough, where Charles himself had been trained (see above). However, from 1888, all engineering students were brought together at Keyham, where instruction was provided as well as accommodation, though much of the students' time was still spent in the Dockyard. Gradually Keyham had become a more academic institution, though of a somewhat austere kind (electric lighting was installed only in 1891 and the Admiralty directed that students should undertake this task themselves!). Higher training continued at Greenwich.

The college had continued to take engineering students on the "old scheme" until 1905, when the last cohort arrived for a five-year course. The college then closed temporarily in 1910, to reopen in 1913 with the first intake of the "new scheme" Lieutenants (E). The engineering officer training arrangements now in place were very different from those which Charles had experienced himself:

- Two years at RNC Osborne, commencing between the ages of 13-15

- Two years at RNC Dartmouth

- Three years in the fleet as a midshipman

- Two years in the fleet as a sub-lieutenant

- Eight months at RNC Greenwich

- One year at RNEC Keyham (for Lieutenants (E) only).

Keyham thus had to provide much higher level, concentrated, expert, professional engineering training than it had done before, in effect, to become a naval engineering university.

Outbreak of War

Charles' role in leading Keyham in its new function was very much the summation of everything he had done and in which he had been involved for the last ten years. But what he might have made of this challenge would never be known, for war was declared just under a year after he took up his appointment. He remained at Keyham until 15th September 1914, when he joined the staff of Sir David Beatty, the Vice Admiral Commanding the First Battlecruiser Squadron, to provide engineering expertise and advice.

Although the flagship was HMS Lion, Charles was accommodated first in HMS Queen Mary. However, in November 1914 she needed to go into Portsmouth for repairs. On 24th November 1914 he transferred to HMS Tiger. Tiger had been rushed to completion at the shipbuilders at the outbreak of war to get her into the fleet and had not been through a lengthy trial period. She joined the Grand Fleet with construction staff aboard working day and night, and Charles' expertise as Squadron Engineer Officer was essential to oversee the process of bringing her up to full effectiveness. She had not had time for full training and work-up, but nevertheless went into action at the Battle of Dogger Bank on 24th January 1915, with Charles on board.

The Battle of Dogger Bank

At 5.45 pm on 23rd January 1915, Admiral Franz Hipper sailed from Germany with battle cruisers Sedlitz, Moltke, and Derfflinger, the large armoured cruiser Blucher, four light cruisers, and two destroyer flotillas comprising nineteen ships. His aim was to attack British and other fishing vessels on the Dogger Bank, which he suspected of providing intelligence on German fleet movements. The operation was intended only to involve his battle cruisers, with their escorting light cruisers and destroyers, but their withdrawal would be covered by the High Seas Fleet, from their base in Wilhelmshaven.

The Admiralty was indeed receiving intelligence on German fleet movements, though not from fishing vessels. Unknown to the German navy, the British had since November 1914 been able to break German wireless codes, and were thus able to read intercepted German messages. The Admiralty therefore knew what Admiral Hipper's plans were, and was able to anticipate him. Some five hours earlier, orders had gone to Admiral Beatty at Rosyth, and Commodore Tyrwhit at Harwich, to take all available battle cruisers, light cruisers and destroyers and rendezvous thirty miles north of the Dogger Bank, and 180 miles west of Heligoland, at 7.00 am the following morning.

The British rendezvous was successful and very soon afterwards the two fleets encountered each other's screening force. Fire was briefly exchanged between Aurora, a destroyer from Harwich, and Kolberg, one of Admiral Hipper's four light cruisers. Hipper was uncertain what forces he faced, and turned his entire force to run for home, heading south-east. Beatty pursued, on a parallel course. As the wind was from the north-east, his ships could then open fire unimpeded by smoke - whereas Hipper's gunners would be in exactly the opposite position. The British ships were able to make exceptionally fast speeds and gradually they gained on the German fleet.

_Map.png)

At 8.42am, at the extremely long range of 20,000 yards, Lion, in the lead, opened fire on Blucher, the slowest of the German ships, and at 9.05 am, Beatty told his squadron to engage the enemy. At 9.15 am, the German ships began to return fire. Tiger and Princess Royal took on Blucher while Lion aimed at Moltke, Derfflinger and Seydlitz. By 9.35 am, New Zealand had come within range of Blucher and had opened fire.

At this point Beatty told his squadron to "engage the corresponding ship in the enemy's line", meaning:

- Lion against Seydlitz

- Tiger against Moltke

- Princess Royal against Derfflinger

- New Zealand against Blucher

Indomitable, the slowest of his ships, was still not within range.

Unfortunately, Captain Pelly of Tiger assumed him to mean something different: that the first two ships, Lion and Tiger, should engage Seydlitz, and so on; partly because he thought in error that Indomitable was already engaging Blucher. His error left Moltke untargeted (the official history says Derfflinger); and left Lion under constant, heavy fire from both Seydlitz and Moltke (Seydlitz had earlier been hit badly, but had been saved from a massive explosion by her crew flooding the magazines, and continued to fire). By 10.52 am, Lion was out of action, listing badly, and losing speed without her port engine.

However, by this stage, Blucher, which had been fired upon by all the British ships as they came up the line, had suffered major damage. At 10.48 Beatty ordered Indomitable, finally coming into action, to attack her. Meanwhile, with Lion dropping back, Tiger began to pass into the van, and so became the primary target. She was hit on the roof of Q turret; on a large compartment below the signal bridge; and also in the boat stowage area, causing a major fire (which was put out, but which caused the German ships to think she must have been lost).

Suddenly, at 10.54 am, Beatty, believing he saw a submarine periscope, and thinking he might be heading into a submarine trap, ordered a 90 degree turn to port. He was also concerned about the German destroyers laying mines. His plan was still that Indomitable should destroy the cripped Blucher whilst Tiger, Princess Royal and New Zealand would overtake and, preferably, annihilate the damaged Seydlitz and perhaps the other two of Hipper's battlecruisers. Realising that a 90 degree turn was too far, he ordered a countermanding signal for a 45 degree turn, to bring his ships back more quickly in pursuit of Hipper. In addition, he also ordered a second signal, "attack the rear of the enemy".

These signals, sent by flag as all Lion's other forms of communication had been destroyed, were misinterpreted by the rest of Beatty's squadron. They took them to mean "attack the rear of the enemy course north east" which was where the Blucher happened to be. Accordingly all the British ships swung towards the crippled Blucher, and away from the pursuit of Hipper's other ships. More or less at the same time, Hipper (most unwillingly) took the decision to abandon Blucher, to save his other ships. With the British ships targeting Blucher, he was able to escape. By 3.30pm, Hipper's fleet, though heavily damaged (apart from Moltke) was safely back home.

Blucher fought hard, but targeted first by Tyrwhitt's destroyers with torpedoes, and then by the four British battlecruisers, her fate was inevitable. She sank shortly after noon, with considerable loss of life. Tyrwhit's destroyers began to pick up survivors, but the crew of a German seaplane, having come upon the battle, and apparently having misidentified Blucher as a British vessel, thought they were watching British ships pick up British survivors, and began to bomb the rescue effort, so the destroyers were forced to withdraw.

Beatty, meanwhile, had commandeered a destroyer, intending to reach his remaining battle cruisers and resume the attack. However, too much time had been lost, and in addition, the Admiralty had signalled that the German High Seas Fleet was coming out (in fact, they came no further than was necessary to protect Hipper's returning ships). Beatty realised the battle was over, and applied himself to getting Lion safely back to Rosyth. Though public opinion regarded the Battle of Dogger Bank as a British victory, Beatty himself was bitterly disappointed at failing to achieve the total annihilation of the enemy for which he had hoped. Nonetheless, for a year thereafter, German capital ships did not venture into the North Sea.

The circumstances of Charles' death were described by Captain Henry Pelly of HMS Tiger in a letter to his widow:

I had arranged with him that when the ship went into action he should accompany me in the Conning Tower to help me with his advice and make notes as they occurred.

He was most probably killed instantly when a shell exploded nearby. Captain Pelly also commented that Charles

had been invaluable to the Tiger during her teething troubles, and a constant help to all onboard.

Burial

Notwithstanding the hits on HMS Tiger, Charles was one of only ten men killed (and the only officer to lose his life in the battle). Five were buried at sea, but three were buried at South Queensferry on HMS Tiger's return to the UK, with full naval honours, and attended by Admiral Beatty and Captain Pelly. Two were buried elsewhere: Able Seaman O'Rourke was buried in Manchester, his home town, and Charles, apparently at his own request, was buried in Tavistock.

The funeral took place on Thursday 28th January, only four days after the battle. It was reported in the Western Times as follows:

HMS Tiger Officer's Funeral at Tavistock

Yesterday afternoon the funeral took place at Tavistock with full Naval honours of Engineer Captain C G Taylor, MVO, who died from serious injuries sustained on board HMS Tiger in the North Sea battle on Sunday last. The body was brought to Tavistock by the 4.38 train from Plymouth, and shortly after the sad procession left for the Parish Church, at the entrance to which the remains, which were conveyed on a gun carriage, drawn by eight stalwart sailors, were received by the Rev H L Bickersteth, curate of Tavistock, who officiated both at the church and at the new cemetery, where the interment took place, and where the Last Post was sounded. The coffin was covered with the Union Jack. There was a carriage full of beautiful floral tokens, and several sailors also carried wreaths. A large number of brilliantly uniformed Naval commanders and officers of the Royal Marines stationed at Tavistock were present. The deceased, it is stated, expressed a wish to be buried at Tavistock.

According to Charles' obituary in the Journal of the Institute of Metals (of which Charles had been elected a member in 1913) Sir David Beatty, in announcing Charles' death in his report of the action, said that "his services have been invaluable" and "expressed the deep regret of all connected with the Fleet". The obituary continued:

This feeling is shared not only by Captain Taylor's colleagues in the Navy, but by a very large circle of constructive engineers, who recognised his special engineering skill and resourcefulness, while knowing also his great administrative and educational ability as displayed in connection with the training of officers, for which he was at various periods of his career directly responsible ... He was in his early years a great athlete, and in all his earlier appointments a valuable leader in athletic exercises, which greatly assisted him in the work of training officers for the Service ... He was a popular and highly efficient naval officer, whose loss will be much felt".

Charles was the first Welsh rugby international to die during the Great War.

Memorials

Charles appears on the Town War Memorial in Dartmouth. His name was evidently a late addition, as it did not appear on any of the three provisional Rolls of Honour published in the Dartmouth Chronicle in 1919 and 1921.

At the time of his death, a full obituary appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 29th January 1915. This makes clear that by the time of his death Charles' family had left Dartmouth, so the impetus for the inclusion of his name on the town memorial must have come from friends and colleagues in the town.

Charles is also commemorated on the Ruabon War Memorial and on a private memorial inside Ruabon church.

His grave in the Tavistock New Cemetery is listed on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database, but is commemorated by a private memorial, which also commemorates the death of his wife Minnie in 1954. Charles is also commemorated on memorials at Blackheath FC, and the Millennium Stadium, Cardiff.

Within a few months of his father's death, Philip Cardwell Taylor joined the RN College. He served in the Second World War, and reached the rank of Rear Admiral.

Sources

We are most grateful to Charles' grandson John Taylor for the information he has provided for this article.

Charles' naval service record is available for download (fee payable) from the National Archives, reference ADM 196/25/446

For sizarships:

- A History of the University of Cambridge: Volume 3 1750-1870, Peter Searby, Cambridge University Press 1997

For Ruabon School:

- History of Ruabon Grammar School

- The Blue Books of 1847 (Reports of the Commissioners of Enquiry into the state of education in Wales)

Bersham Church (Plas Power Chapel)

Rugby:

Many thanks also to Gwyn Prescott of the World Rugby Museum blog for his article on Charles Gerald Taylor.

- "Into Touch: Rugby Internationals Killed in the Great War" by Nigel McCrery, Pen & Sword Military, 2014

- Rugby Football history

Royal Navy Engineering Officer Training:

- Educating the Royal Navy: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Education for Officers, by H W Dickinson, publ Routledge, 2007

- The Royal Naval Engineering College, Keyham and Manadon

James' Cardwell's brewery at Whittle Springs

Naval service:

- Comus-class corvettes (Wikipedia)

- Torpedo Boats (Wikipedia)

- Torpedo Gunboats

- Torpedo Boat Destroyers:

- The Engineer, 1st January 1897

Dogger Bank:

- The account of the battle is based principally on that in Castles of Steel, by Robert K Massie, publ 2007, Vintage Books.

- Casualty figures are from naval-history.net

Obituaries available online:

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Taylor |

| Forenames: | Charles Gerald |

| Rank: | Engineer Captain RN |

| Service Number: | |

| Military Unit: | HMS Tiger |

| Date of Death: | 24 Jan 1915 |

| Age at Death: | 51 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of Dogger Bank |

| Place of Death: | |

| Place of Burial: | Tavistock New Cemetery |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Private Memorial: | Ruabon Church & Tavistock New Cemetery |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Ruabon War Memorial |