Leonard Rolfe

Leonard Rolfe was not a native of Dartmouth and his name does not appear on any of the public memorials in the town. However, his wife Thirza came from Strete, near Dartmouth. Presumably for this reason, his obituary appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle. He is included on our database for this reason.

Family

Leonard Rolfe was born in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire in 1886 and baptised at St Mary's Beaconsfield on 21st November 1886. He was a younger son of John Rolfe and his wife Mary Ann Lesley (the marriage is also recorded in the name of Lidgley but this appears to be a mistake). They were both born in Beaconsfield.

John Rolfe was a chimney sweep, though he also worked as an agricultural labourer. He seems to have learned his chimney sweeping in London - the 1871 Census recorded him at 41 Margaret Street, Clerkenwell, aged 17, a "sweep and servant", sharing the property with a W Field, also a chimney sweep. But by the time of his marriage to Mary Ann Lesley on Boxing Day, 1874, he had returned to the more rural surroundings of Beaconsfield. In all likelihood, he had known Mary Ann from childhood, as she had been born and brought up in the town - she was the eldest daughter of Edward Lesley, a carter.

By the time of the 1881 Census, the couple had three children. John was working on a farm as a labourer - Mary Ann also worked, probably at home, as a "needlewoman". At that time the family lived in Aylesbury End. By 1891, there were six children at home, including Leonard, aged 5, and they had moved to Windsor End, at the other end of the town. John had gone back to chimney sweeping. The family remained in Windsor End, and John remained a chimney sweep. By 1901, several of the older children were at work - Mary, aged 20, was a housemaid; Elizabeth, aged 16, a beadwork trimmer; and Leonard, aged 14, worked as a "shop boy" for a grocer.

In 1911, the family was still living in Windsor End. John was doing labouring work. The return records that the couple had nine children in all, two of whom had died by the time of the Census. Four were still living at home. Elizabeth was now working as a laundry maid. Leonard, age 24, was a "jobbing gardener" - his younger brother Alexander, age 22, also worked as a gardener. No occupation was given for the youngest, Arthur, aged 19.

In early 1915, Leonard married Thirza Wallace. Thirza was born in Strete, between Dartmouth and Kingsbridge, Devon, on 30th July 1886, and baptised at St Michael's, Strete, on 26th September 1886. She was a younger daughter of Samuel Wallace and his wife Kitty. Samuel was a farm labourer.

Thirza obtained work in domestic service and by 1911 she was working for Basil Humbert Joy and his wife Mary at Cherry Tree Cottage, Beaconsfield, as a lady's maid, one of three servants. Basil Humbert Joy was, by 1911, a consulting engineer; but previously he had been the manager of Simpson, Strickland & Co, one of Dartmouth's leading engineering and shipbuilding firms. He and his family lived in Kingswear at the house called "The Mount", and played an active part in the life of Dartmouth and Kingswear. Two of his children were born in Kingswear. However, for "reasons of health" (according to Grace's Guide) he left his job at Simpson Strickland in 1910, and returned to work in London. It seems reasonable to assume that Thirza went to work for the Joys whilst they lived in Kingswear and then moved to Beaconsfield with them when they left Devon.

Service

Leonard's service papers, like so many, have not survived. He joined the 6th Battalion of the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. This was a new Battalion formed at Oxford in September 1914 as part of Kitchener's Second Army. Comparison of Leonard's service number, 11923, with those of members of the Battalion whose papers have survived, suggests that he joined around the time the Battalion was first formed (number 11675 joined up on 29th August 1914, and number 11744 on 13th September 1914).

The Battalion was part of 60th Infantry Brigade, in 20th (Light) Division, and spent the autumn of 1914, winter and early spring of 1915 around Aldershot. Leonard and Thirza married in Buckinghamshire during this period. Subsequently the Battalion moved to Lark Hill, Salisbury Plain. They arrived in France on 22nd July 1915. The 1914-1915 Star Medal Roll for the Regiment shows that Leonard had already been promoted to Sergeant by the date of disembarkation.

By 9th August 1915 he and the rest of the Battalion were receiving their first instruction in trench warfare near Bailleul. For the next eleven months, they took no part in any major engagement - their role was to hold various parts of the line. Nonetheless, over this period they sustained nearly 300 casualties - two officers and 71 men killed, and six officers and 214 men wounded.

When the Somme offensive began on 1st July 1916, the 6th Battalion was in the trenches at Zillebeke, and remained in that part of the line for the next three weeks. Though not part of the great attack, the line around Ypres was far from quiet - from 1st-24th July, one officer and eleven men were killed, and three officers and 52 men wounded.

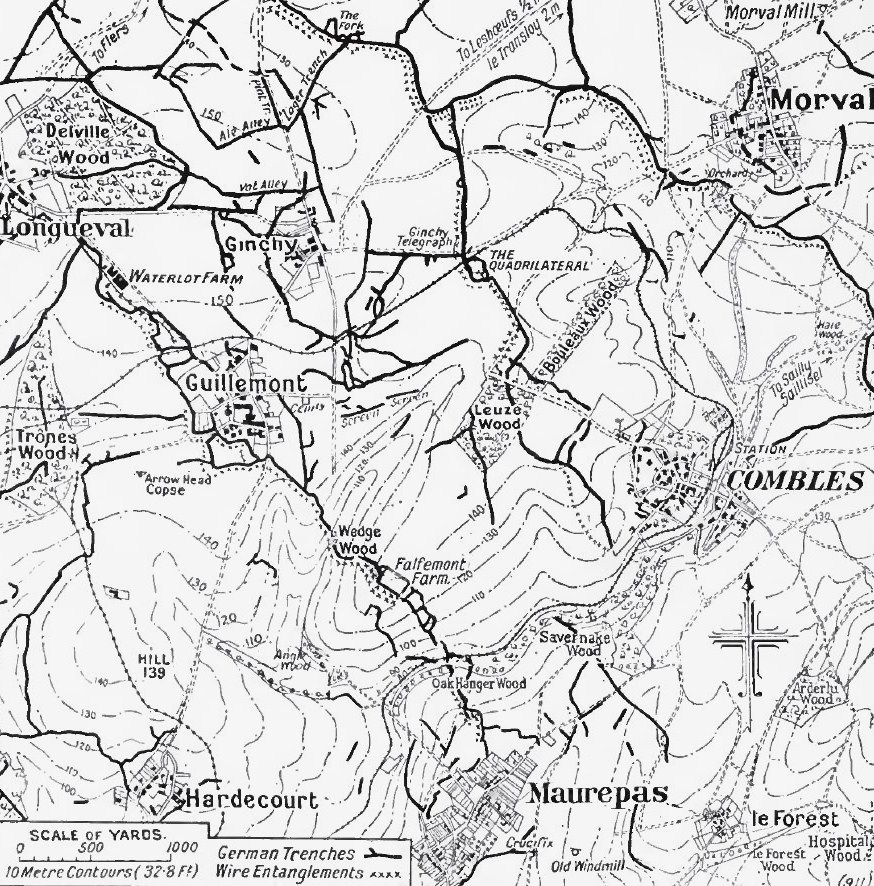

The Division left the Ypres area on 25th July, arriving in the trenches opposite Serre (in the northern half of the Somme front) on 29th July, where they remained for a week. After a week's relief, they moved to the southern sector of the front, near Ville-sous-Corbie (now Ville-sur-Ancre). For the next ten days they provided working parties for support and front-line positions in the Trones Wood area. An attack was in preparation, with the aim of overrunning all the remaining "start-line" objectives - High Wood, the heavily fortified villages of Ginchy and Guillemont, and the strongpoint of Falfemont Farm.

Finally the Battalion found itself in line for an attack when they were temporarily attached to the 59th Brigade for the attack on Guillemont on 3rd September. As Guillemont was part of the original German line of defence on the Somme, it was still strongly fortified. Running more or less south from the south-west corner of the village were two sunken roads, which had given much trouble in earlier attempts to capture it.

The plan was to attack the village from the north, west and south. The 59th Brigade had the southern part of the village as their objective, with the aim of reaching a road on the eastern side, which runs from a feature known as Wedge Wood, to the south-east of Guillemont, to the village of Ginchy, a little to the north-east. Their intermediate objectives were the two sunken roads. Leading the attack were the 10th and 11th Battalions of the Rifle Brigade, with the 6th Battalion following immediately behind (along with the 7th Somerset Light Infantry). On their right, 5th Division attacked Falfemont Farm - see the story of George Peters.

Although the three leading companies of the 6th Battalion "lost all their officers and all their Company Sergeants Major" before reaching their second objective, the attack was a success. The Wedge Wood-Ginchy road was reached "with very little opposition" at 2pm; the attack was not taken further forward at that point, because the 5th Division had not yet reached Leuze Wood (they did so later that evening). The 6th Battalion therefore consolidated their position, despite "a shortage of tools".

The official account by the Battalion's commanding officer, Lt Col E D White, recorded that "eight company officers, 72 NCOs and about 200 men were casualties, mostly early in the attack ... nearly all the losses ... were from shell and machine gun fire before reaching the second Sunken Road, and more especially before reaching the first Sunken Road." He also commented, perhaps with a slight air of surprise, or perhaps just quiet gratitude, that "casualties from our own barrage were slight, if any at all".

An account of the village soon after the attack observed that "Guillemont was blotted right out, not one brick standing on another - nothing but a sea of crump holes of all sorts and sizes".

6th Battalion was relieved from Guillemont progressively on 5th and 6th September, and over the next few days, changed camp several times whilst doing a certain amount of training. On 16th September, they were back in the front line not far away, at Waterlot Farm, which they held for five days, with six men killed and eight wounded.

On 21st September, they were relieved and withdrew to the camp at the Citadel, near Fricourt, but they were allowed little rest, once again changing camp several times before going into the trenches again to the north of Trones Wood, until 6th October.

Meanwhile, yet a further general attack was under preparation. To General Haig and his planners "it seemed that the hammer blows of the previous months seemed to be brearing fruit at last. There were some indications that the German resistance was weakening and the tantalising possibility that they might at long last be on the very verge of collapse". But, as Peter Hart also points out: "Miserable letters home [from prisoners] did not mean that the men would not fight when they had to - otherwise half the British Army would have been good for nothing". The plan was for the Fourth Army to continue the attack along the "Le Transloy Ridge". Very heavy rain delayed the start, which finally took place on 7th October.

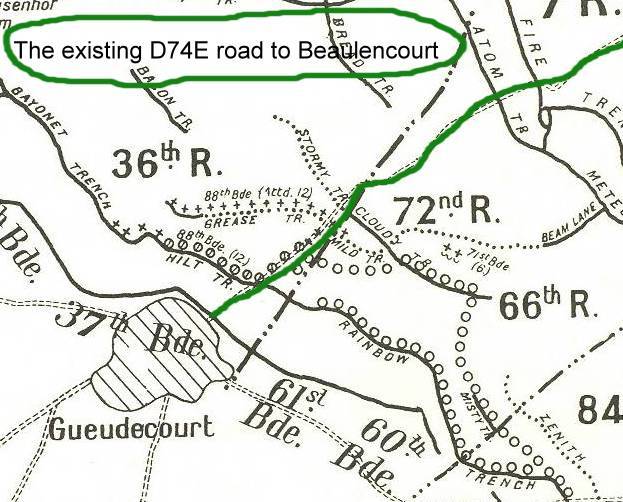

The Battalion had by this time returned to 60th Brigade, which attacked on the right of 20th Division's front, to the south east of the village of Gueudecourt. They were to follow a north-easterly line of advance to approximately between the villages of Beaulencourt and Le Transloy, on the main road from Bapaume to Peronne (now the D917). This time, the 6th Oxford and Bucks were in the Brigade front.

Tactics had improved considerably from earlier in the Somme offensive. There was no preliminary bombardment, thereby allowing for a measure of surprise. The troops attacked behind an intense creeping barrage, commencing at zero hour, and moving forward at about 50 yards per minute - the importance of leaving the front line trenches quickly and keeping up with the barrage was stressed in the Battalion's orders. Their first objective was "Rainbow Trench", just north of the village of Gueudecourt, and the second objective, the second line of German defences to the north-east, was "Cloudy Trench". Once gained, the position was to be consolidated for the next phase of the attack - a "bite and hold" approach, though the aim was to push forward with fresh troops for the next phase as quickly as possible, to prevent the German defence from regrouping.

The report of the attack, this time by Major J E Osborne (Lt Col White having been invalided back to England) described the attack as a success:

On 7th October zero hour was 1.45pm ... the Battalion left its trenches and attacked Rainbow Trench (1st Objective)... the leading waves moved out of the British line close up to our barrage, arrived at the German barbed wire (about 40 yards in front of our trench) and lay down. The enemy had manned his parapet some 60 yards to our front, and was delivering a very hot fire from six machine guns and from rifles, to which our troops replied. Shortly after the advance began again; some men were able to crawl through the wire; others were able to move round through the gaps; others, by placing their feet on the top strand of the wire, were able to get through. The wire obstacle was one single length of barbed concertina wire, extending along the whole of the frontage of the Battalion's left company. It was about 2 ½ft high, and appeared more of an alarming obstacle than it actually was.

During the period zero to zero+4 minutes the enemy's machine gun fire was very intense, but at the latter time was silenced. The enemy then left their trenches unarmed, and ran back towards their second line. During their retreat our Lewis guns did considerable damage to them; large numbers were seen to fall, and few Germans got back, those remaining in their front line being bayoneted or captured.

The advance from the first German line to the second ... was accomplished with comparatively little loss, although some casualties occurred from snipers on our extreme right, who took advantage of that flank being temporarily in the air. Shortly afterwards a portion of the Division on the right pushed forward their attack and commenced digging in; thus, by joining up with our troops, they made our extreme right secure. The consolidation of this position was at once commenced, our troops having reached their final objective ...

But success was secured at a fairly high price:

The Battalion lost most of its officers early in the attack; the Company Commanders of A, B and C were killed, and D Company Commander was severely wounded. Casualties amounted to 13 officers and 230 other ranks.

The following day, 8th October, the position was successfully consolidated, and 6th Battalion was relieved that night, to Bernafay Wood; to be followed by a month of rest and training. For them, and for Leonard, the Battle of the Somme was over.

Death

The available records give no clue as to when during the 6th Battalion's time on the Somme Leonard was wounded - it may have been in the September attack on Guillemont, in the period afterward in which the Battalion was holding the front line near Waterlot Farm, or possibly, in the October attack near Guedecourt - though if it was the last of these, he must have been picked up quickly afterwards, to have reached as far back down the casualty evacuation chain as Rouen within five or six days. We know only that he died of his wounds in one of the hospitals in Rouen on 13th October 1916. The city, well behind the lines, was a major logistics centre, with many base hospitals.

The British and Victory Medal Roll for the Regiment shows that although Leonard's substantive rank was still that of Sergeant at the time of his death, he had achieved acting rank of Warrant Officer Class II.

Commemoration

Leonard was buried in the St Sever cemetery to the south of Rouen.

When the Imperial War Graves Commission engraved his headstone in the St Sever Cemetery, Thirza requested the words:

At home, Leonard is commemorated on the Beaconsfield War Memorial, which was erected at the entrance to Windsor End, close to his family home.

Sources

The account of the experiences of the 6th (Service) Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry comes from the extracts from the Regimental Chronicles available on the Lightbobs website

Somme 1916, A Battlefield Companion, by Gerald Gliddon, The History Press, 2016

The Somme, by Peter Hart, Cassell, 2006

For the Beaconsfield War Memorial, please see the Buckinghamshire Remembers website and the Beaconsfield and District Historical Society website

For Basil Humbert Joy, please see Grace's Guide to British Industrial History

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Rolfe |

| Forenames: | Leonard |

| Rank: | Sergeant |

| Service Number: | 11923 |

| Military Unit: | 6th Bn Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry |

| Date of Death: | 13 Oct 1916 |

| Age at Death: | 30 |

| Cause of Death: | Died of wounds |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of the Somme |

| Place of Death: | Rouen, France |

| Place of Burial: | St Sever Cemetery, Rouen, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | No |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | No |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Beaconsfield War Memorial; Dartmouth Chronicle Obituary |