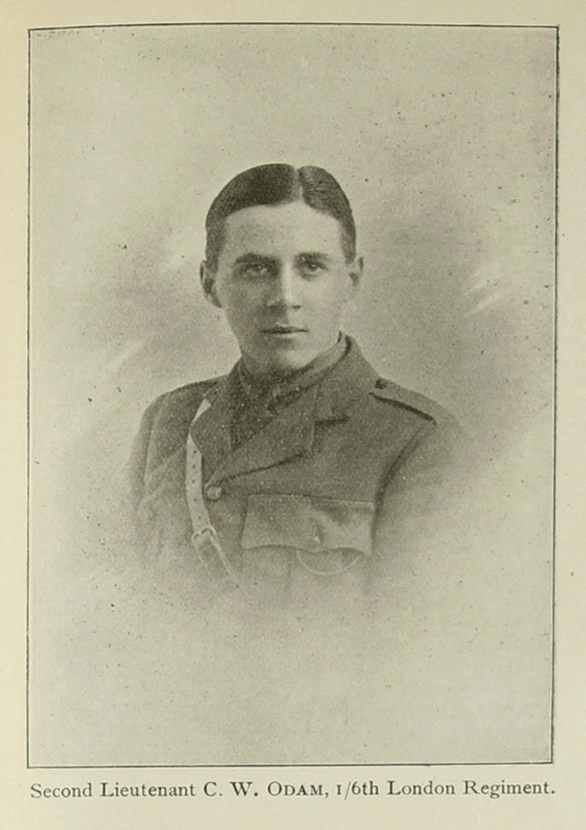

Cecil Wilfred Odam

Family

Cecil Wilfred Odam was born on 6th July 1897 in Dartmouth. He was the younger son of Charles Odam and his wife, Ellen Maria Bradford.

Charles and Ellen came from North Devon. Charles was born in the village of Filleigh, near South Molton. He was the son and grandson of Master Tailors, and he too went into the Tailoring business. The 1881 Census recorded him aged 18 working with his father in South Molton. Ellen was the youngest daughter of John Bradford, who at the time of her birth lived at Lapford, where he worked in the office of Mr Croote, steward of the Earl of Portsmouth's estate.

Although his professional career was as a land-agent and accountant, he was more notable for his role in "the life of village Non-conformity in North Devon", according to his obituary in the North Devon Journal (14th December 1905). The newspaper described him as "a man of considerable gifts, and of deeply religious character, he was a singularly able and impressive preacher, and it was for years his custom to devote his Sundays to fulfilling preaching engagements in village chapels, while he frequently spoke at week-night meetings, his services being in great demand throughout a wide district". At the time of the 1881 Census, Ellen Maria was still living at home with her parents, John and Maria Bradford. The family had moved to Barnstaple, and Ellen worked as a grocer's assistant.

How Charles and Ellen met is not known, but they married on 27th March 1889 at the Independent Chapel, South Molton. The announcement of their marriage in the Exeter Flying Post of 30th March 1889 indicates that Charles had already moved to Dartmouth, perhaps on his father's retirement from tailoring. It seems that at about the time of his marriage, Charles acquired the tailoring business of John Humphrey Hurrell, who had been a prominent member of Dartmouth's community, having been Mayor in 1870 and actively involved in many aspects of public life. The first advertisement for Charles' business that we have been able to trace, appears in the Dartmouth Chronicle on 8th March 1889. From then on, few editions appeared without an advertisement for his tailoring and outfitting business, which clearly did well.

The 1891 Census duly recorded Charles and Ellen living in Clarence Street, and their eldest son, Charles Leslie, was born there on 26th February 1893. In August 1896, the family and the business moved to a better business location at the very centre of Dartmouth, at Spithead. Cecil was born there the following year. As might be expected given Ellen's background, the family were members of the Flavel Congregational Church in Dartmouth.

By the time of the 1901 Census, the family no longer lived "over the shop", but on Ridge Hill - the business remained at Spithead. A governess had been engaged for the children. In October 1910, the family moved a little further up the hill towards Townstal, to "Mount Boone" (one of several houses built on the site of Mount Boone House between 1905 and 1907) - they were recorded there at the time of the 1911 Census.

Both Charles and Cecil attended Taunton School, founded in 1847 as a boys school for non-conformists. They did well, being recorded as prizewinners on a number of occasions. The Taunton Courier also chanced to record that Cecil was a good singer - at the dedication of a memorial window to Lord Winterstoke, whose father and uncle had helped to found the school, and who had donated the chapel and other facilities, Cecil was the member of the school choir who sang the solo in the hymn.

Neither of the two boys followed their father and grandfather into the tailoring business. Charles went up to Sidney Sussex, Cambridge, in 1911, graduating in the summer of 1914. He went into medicine; and Cecil evidently intended to follow him in this career. However, when war was declared, Cecil was a little over 17, and had just left school. At that age, he would have been just over the minimum age for a temporary commission, though overseas service was limited to those over 18. Such an application would have required his parents' consent - perhaps they refused it, or perhaps he thought he would wait until he was of the age when he could go overseas immediately.

Cecil therefore began an undergraduate degree in medicine in London, entering the Medical College in October 1914 in London, at the London Hospital (now the Royal London), and passing his first MB in July 1915. But he never completed his training. He had joined the OTC at London University, and had also been a member of Taunton School OTC. He had therefore some military experience, and he obviously wanted to use it. Aged 18, he applied for a commission and was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the 1st/6th Battalion London Regiment on 16th January 1916.

Service

The 6th Battalion of the London Regiment was a unit of the Territorial Force, but when war was declared, over 90% of its members volunteered for service overseas. The battalion went to France in March 1915 as part of 140th Brigade, in the 47th Division. Very soon after the outbreak of war, a second battalion was raised to supply drafts to the first, until a third, or reserve, battalion was authorised in March 1915, to raise and train men for both the 1st/6th and the 2nd/6th. The 2nd/6th then also went to France, in January 1917.

By the time Cecil joined the 1st/6th, the training battalion was based at Fovant, on Salisbury Plain, where, according to the Battalion's Official History, they:

took over the northern section of some newly erected hutments, forming an immense camp on the southern slop of a hill facing the Compton Down, against the steep sides of which were buit innumerable rifle, machine-gun, and bombing ranges ... Above and behind was a large parade ground, soon to be bounded on the north by a carefully-planned bayonet training course. The messing arrangements, for both officers and men, were excellent.

Cecil spent the first five months or so of 1916 in training. The obituary published in the London Hospital Gazette in 1917 stated that he went to France in May. Oddly, there is no mention in the Battalion War Diary of him joining during May or June (or indeed, at all). However, the Battalion History records that while they were in billets at Bruay, south-west of Béthune, fourteen officers and over one hundred NCOs and men arrived as reinforcements, to replace losses incurred during fighting on Vimy Ridge. The War Diary names thirteen officers joining at this time - presumably Cecil was the fourteenth.

Assuming this is correct, Cecil's introduction to trench warfare began on 12th June, when the Battalion moved from Bruay into the trenches at Souchez. According to the Battalion History:

It seemed that the battalion was moved to whatever sector required work on its defences ... wherever it went, it dug, it sandbagged and it wired...

During the rest of June, and for most of July, the Battalion returned to the trenches several times in this sector. Casualties were relatively few and activity levels relatively low on both sides. On 24th July, while they were still in the trenches, the War Diary records that the Brigade Major visited at night, to tell them that the Division was shortly to be moving south. They were to be transferred to the Somme.

The Battalion marched south-west in intense heat, eventually reaching Millencourt-en-Ponthieu, just north of Abbeville, on 5th August. The march was hard, but the countryside, untouched by war, made a most welcome change from the mining villages and trench mud of the Lens area. At Millencourt they began their preparation for the Somme, practising bayonet fighting; rapid fire, including on the move; advancing in line by short rushes; bombing; and other necessary skills. All this was as important for young officers like Cecil as it was for the men. On 8th August the writer of the War Diary observed:

The Battalion carried out an attack on enemy's first line system of trenches, these being marked out on the ground by flags. Officers being inexperienced, much time was devoted to instructing them how to handle their units. It is curious that although these Officers have served for lengthy periods in England they know so little.

On 11th August, there was a practice attack for the whole Brigade. They were required to capture all three lines of the enemy position, behind an artillery barrage represented by men waving red flags. How useful this was, is open to question; on 14th August, the writer of the War Diary recorded that:

The exercise consisted of an attack on Enemy's trenches. These proved too much for ordinary imagination, with the result that in the absence of defined trenches or objects to mark position of same, the 1st and 2nd lines, led by the Adjutant, gallantly swept forward and took the support Battalion's objective, much to the excitement of the Brigade Major, who galloped wildly about in all directions".

On 16th August, the Battalion marched to the Forest of Crecy, for a practice attack in woods. The attack was "fairly" successful though "all ranks too noisy".

Five days later they were on their way to the Somme battlefield, arriving at Franvillers, south-west of Albert on the Albert-Amiens road, on 23rd August. Here they continued to train hard, apart from a day off on Sunday 27th August, "much to the relief and joy of all ranks", according to the War Diary. On 2nd September, another Brigade practice attack was staged, which seems to have been more successful, except that "an aeroplane was supposed to cooperate and communication maintained by flags and signals", but the aeroplane did not turn up. Significantly, a key aspect of the practice was an infantry attack behind a creeping barrage, an artillery technique which had by now been accepted as fundamental to any successful attack. There was also more practice in attacking in "wood fighting formation".

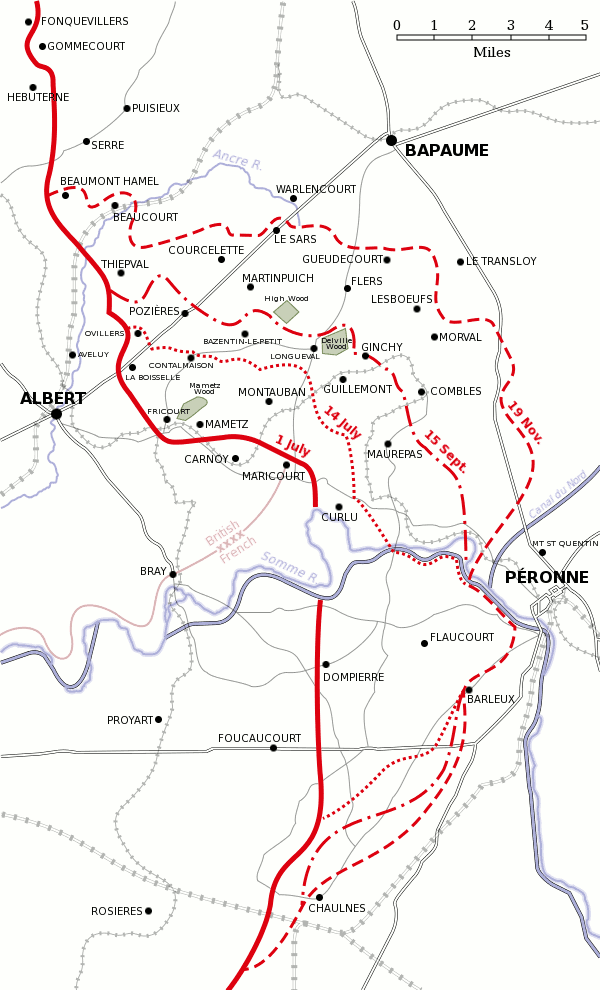

The Battle of Flers-Courcelette

The 47th Division, the 1st/6th Battalion, and Cecil, had been brought to the Somme for the offensive planned for the middle of September, which had the aim of capturing the original German third line defensive system (which it had been hoped might fall on 1st July).

General Haig hoped that this phase of the Somme would prove decisive, and that the much hoped-for breakthrough would finally follow. His plan was to:

"...establish a defensive flank on the high ground south of the Ancre, north of the Albert-Bapaume road, and to press the main attack south of the Albert-Bapaume road with the objective of securing the enemy's last line of prepared defences between Morval and Le Sars, with a view to opening the way for the cavalry".

During late August and early September, attempts had been made to establish a good "start line" for this third offensive, including the attack on Ginchy (see the stories of Robert Anderson Hatch and William Marks Carpenter). But certain strong points still remained, most notably, High Wood. This had first been attacked on 14th July and had been attacked again many times since, but had still not been taken (see our article on the 8th Devons at High Wood).

Furthermore, although the German Third Line was not as strongly fortified as the original defences attacked on 1st July, it had been significantly strengthened over the course of the summer, and there was now a new First, Second and Third Line of defence to overcome. And although all was not well with the German Army - as indicated by the replacement of General Falkenhayn by General Hindenburg on 29th August - it was not the case that the Army, or the country, was on the point of collapse.

However, the British now had a secret weapon - the tank. General Haig had been quick to see the tank's potential and had strongly encouraged as many as possible to be produced so that they could be put to the test. But as a completely new weapon, there could be no experience of how they might most effectively be deployed, and how infantry and artillery should operate with them.

After much debate, it was decided that the tanks should be used in small groups along the front line, in advance of the infantry, targeting specific German strong points. In particular, eighteen were planned to be used to lead the assault on the village of Flers, which was seen as key to taking the new German second line.

The tanks were supposed to reach their first line objective five minutes before the infantry, and gaps about 100 yards wide were to be left in the creeping barrage for them. For the second line, the infantry and tanks were supposed to advance together, under a new creeping barrage. The third line was beyond the range of the field artillery, so the plan was for the tanks to flatten the wire and then use their weapons to suppress the German defences. If the tanks were held up, the infantry were to press on; if the infantry was held up, the tanks were to wait, or, if necessary, turn back. In the meantime, they were to be kept as secret as possible, to maximise the shock of their first appearance, and to give the enemy no opportunity to think about how best to deal with them.

This is perhaps why the training undergone by 1st/6th Battalion included no mention of tanks, although some troops going into battle on the Somme were apparently given the opportunity to train with them.

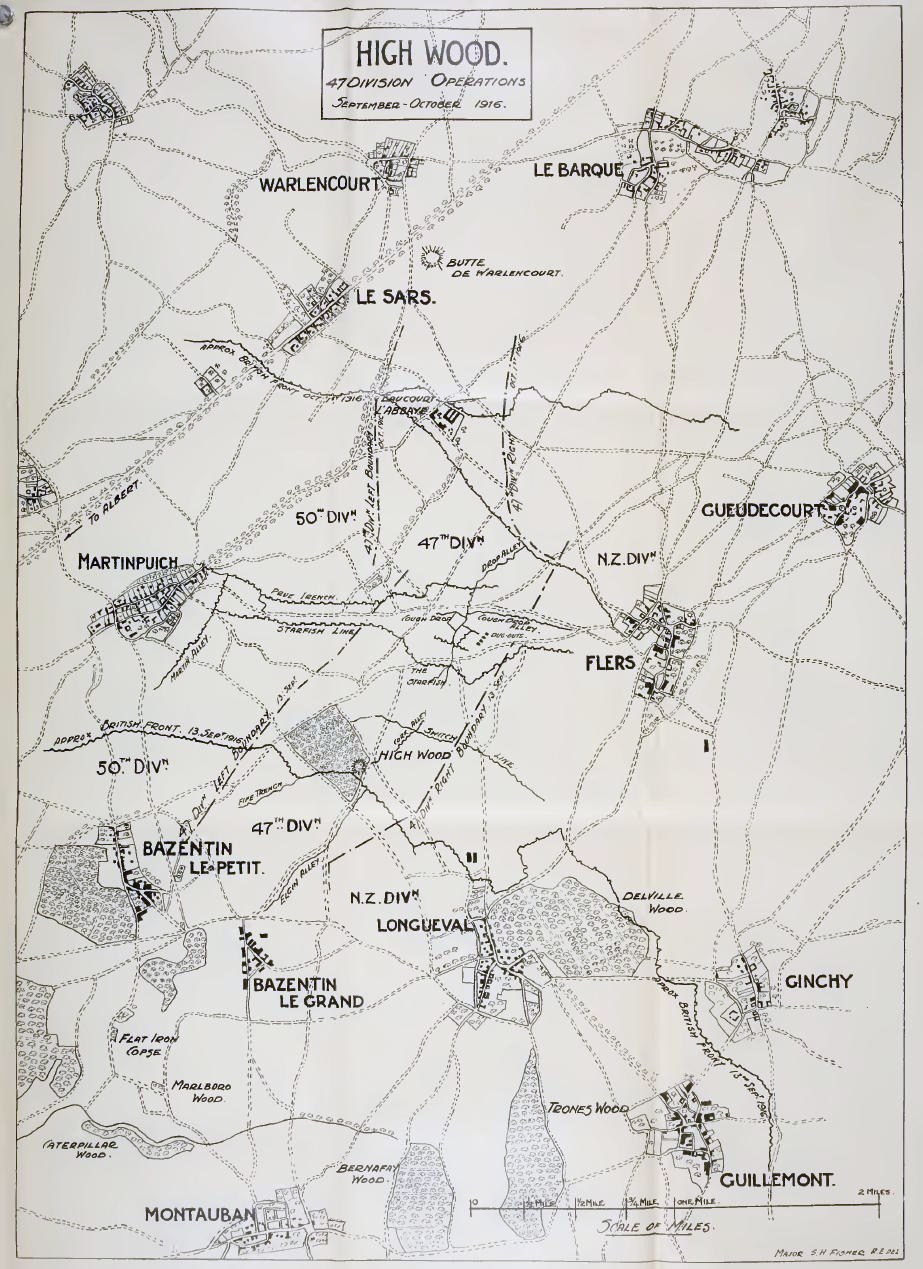

47th Division's task in the attack was, first, to clear High Wood, then to take the second line of defence, called the Starfish Line; then to swing round eastwards and take a section of the third line of defence, called the Flers Line, joining up with the New Zealand Division on the right; and finally, to form a defensive left flank, intended to become a temporary front line, facing north.

141st Brigade, on the left of the Divisional front, was to capture the wood. 140th Brigade, on the right, was to take the three lines of the trench system lying to the right (east) of the wood. Each of 140th Brigade's battalions had a separate task:

- the 1st/7th Battalion London Regiment was to attack the first line, called the Switch Line, on the right, and then link with the New Zealand division on the Brigade's right

- the 1st/15th Battalion London Regiment was also to attack the first line, on the left, working along the eastern edge of High Wood to suppress fire directed from there

- the 1st/8th Battalion London Regiment was then to continue the advance to the Starfish Line, passing through the ground held by the first two battalions

- finally, the 1st/6th Battalion was to take the advance to the final stage, attacking the Flers Line, over all the ground taken by all three battalions

Unfortunately, the General commanding III Corps, which included the 47th Division, had decided that, as the British and German lines were close together in High Wood, he would forego the creeping barrage for the initial attack (fearing friendly fire casualties), and rely on his four tanks (followed up by the infantry) to capture the front line.

Some indication that complete reliance on tanks might prove a flawed approach was provided as the 1st/6th prepared to move up into the assembly trenches. The War Diary reported that "the road leading into Caterpillar Valley was blocked up by a tank which capsized and completely stopped the way". Eventually they got round the obstacle and were able to reach their assembly positions just as the 1st/7th attacked, at 6.20am on the morning of 15th September.

Although the 1st/7th, attacking on the right, captured their first objective, this brought forth a heavy German artillery barrage on the British front line, and on the 1st/6th waiting to advance. The War Diary observes that "Some little loss was caused ... but in the circumstances losses were slight". The Battalion's History quotes a letter from an officer (unnamed) describing this moment:

The Sixth was now experiencing what is probably one of the greatest tests a soldier has to face - waiting. We had to wait an hour before "going over", and the enemy's retaliatory barrage was hitting the trenches with unpleasant frequency. It was a most unnerving experience; officers were wondering if they would be alive to lead their troops, and if so, would there be any troops to lead, and men were wondering if they would be alive to attack, and if so, would there be any officers left to lead them. It was a most interesting thing to note the different reactions of different temperaments - some were laughing and joking in high-pitched voices, others were white and tight-lipped, with flashing eyes and jerky movements, but all were keyed up for the great moment.

In High Wood, the tanks achieved nothing. Only one succeeded in reaching the German front line. One ditched in a shell hole, and another in no mans land. According to the testimony of an RFC pilot flying over High Wood on a contact patrol:

One [tank] had gone over both trenches, rather beyond the Boche line, and there had stuck. It was very heavily shelled for about ten minutes ... after smouldering for some time it burst into flames. The other two turned over on their side in our own trenches.

The final tank lost its way around the southern border of the wood (visibility from inside the tanks was extremely limited), and turned east in an effort to find clear ground. Waiting to advance, the 1st/6th found themselves actually under attack from their own side. The Battalion's War Diary reported that:

One of the tanks which was cooperating on the left swerved to the right, across the front of the 6th Battalion, and stuck partly across Worcester Trench [where they had assembled]. The Commander promptly opened a vigorous fire on our men, killing and wounding several. After a somewhat heated argument with the Officer commanding the Company affected, the tank ceased fire and took no further part on the day's proceedings.

At 8.20am, the 1st/6th advanced, in four waves. From right to left, the order of attack was C company, linking with New Zealand troops; B company; D company; and A Company on the left, linking with the 1st/15th Battalion. Each wave consisted of one platoon from each of the four companies - the first, second and fourth waves were led by Platoon Commanders, and the third wave by Company Commanders and Company Sergeant-Majors. Cecil's company does not seem to have been recorded so we don't know exactly when, or where, he attacked. However, he was most probably one of the Platoon Commanders.

With the benefit of all their prior training, the advance was, according to the Battalion History, "like a drill movement"; but this did not last. Without the tanks, and without the creeping barrage, the 1st/15th Battalion on the left had been exposed to heavy rifle and machine gun fire, and casualties were very high. The 1st/8th, attempting to reach the second objective, also suffered similarly. Nor had the 141st Brigade achieved their objectives, for the same reasons.

As it advanced, the 1st/6th was thus "exposed to a very severe machine gun and rifle fire and had to fight its way forward. [It] met with considerable opposition from the Starfish line and adjacent trenches [since this had not yet been taken]".

The position appears to have been saved by 140th Brigade Trench Mortar Battery, which by 11.40am had fired 750 mortar shells into High Wood. Under this onslaught, and following intense bombing attacks from determined members of 1st/8th Battalion, the Germans began surrendering. By the middle of the day the wood was finally taken, together with the first line trench running through it, called the Switch Line.

But at that point in the day, the Starfish line still had not been taken. Further, a strongpoint behind it known as the "Cough Drop" (because it was shaped like a lozenge) provided "considerable opposition". The Battalion History provides a description of the advance at this stage by Captain M J Macdonald, commanding C company, who survived the battle, though wounded:

As a result of enfilade fire, whole waves were mown down in line, but some thirty of C Company, making use of what dead ground there was, fought on until held up at the Cough Drop, where a machine gun was very active. A few lucky shots and this was put out of action, and a sudden assault with fixed bayonets captured the position. Some sixty prisoners were taken, as well as two machine guns and quantities of ammunition and stores.

The War Diary states that one of the Cough Drop machine guns was captured in the entrance to the German Dressing Station, and continues "at this time the Battalion had lost heavily". The Dressing Station, however "was very complete and extremely well adapted for its purpose, and was very well supplied with all medical necessaries" - facilities which must have come in most useful in the circumstances.

What was left of the 1st and 2nd wave of the Battalion's advance went on forwards, and reached the Flers Line, but according to Captain Macdonald "this was very strongly held by a pocket of enemy troops, and Lt Pickering and his gallant little band all became casualties". Indeed, Lt Pickering was killed.

Captain Macdonald therefore decided to consolidate the position in the Cough Drop, where he was joined by Captain Brooke, of B Company, with twenty NCOs and men. Links were made with the New Zealanders on the right.

At this point, according to the War Diary, there were only two officers and about 100 men left in the Battalion "the casualties in the advance having been very severe". However, despite heavy casualties amongst their crews, all eight of the Battalion's Lewis guns were successfully brought into the Cough Drop, further strengthening the position.

During the night "all available officers and men" normally employed on duties in the rear were brought up, and a company of 1st/22nd Battalion London Regiment, over 200 strong, joined the Cough Drop garrison from divisional reserve.

The following day, according to the 1st/6th's War Diary, "The Germans beyond little artillery fire were quiet" but to add insult to injury, the Battalion was once again subjected to friendly fire:

The Cough Drop trenches were subjected to a very heavy artillery fire by our own artillery for a brief period, causing some casualties.

(The word "some" is a correction in the original from "many").

The Battalion hung on in the Cough Drop for a further day. On 18th September, 200 men from 1st/8th Battalion and 100 from 1st/15th were brought up and, together with the remaining 100 of 1st/6th, an assault was launched on the Flers Line. According to the War Diary, "there was little opposition and losses were slight", though yet another officer was killed and a second wounded. Drop Alley, a trench running from the Cough Drop to the Flers Line, was taken (though subsequently lost). In the meantime, the Cough Drop continued to be subjected to heavy artillery fire. The remaining members of 1st/6th Battalion were finally relieved from the Cough Drop on 20th September.

Elsewhere, there was more success; famously tank D-17 reached Flers and entered the village, though its commander, finding himself on his own there, turned round and returned to find the infantry at the Flers Line. Two other tanks, D-16 and D18, were able to provide attacking infantry on the west with valuable support, and Flers was eventually taken.

Overall, 49 tanks were employed, of which 32 reached the starting point. Nine went ahead of the infantry, as planned; nine failed to catch the infantry, but helped in clearing captured ground; nine broke down; and five were abandoned in the centre of the battlefield.

Death

There seems to have been some doubt after the action about what had happened to Cecil.

In the Battalion War Diary, after the entries for the month of September 1916, is an undated page, listing casualties during the month. Amongst the officers, during the period from 15th - 18th September:

- seven were killed in action, six on 15th September, the first day of the attack, and one on 18th

- nine were wounded, seven on 15th September, one on 17th, and one on 18th. Two died of their wounds shortly afterward

- one suffered from shell shock, on 17th September

- three were declared as missing on, or from, 15th September, one of whom was Cecil.

Figures for other ranks are not shown in individual detail, but 51 were killed in action, 319 were wounded, and 67 were missing.

This is the only mention of Cecil in the Battalion's War Diary.

The Soldiers Effects Register showed Cecil as "presumed dead" with effect from 31st May 1917; and the Medal Roll for the 1st/6th Battalion, drawn up after the war, also recorded him as "missing 15th September 1916".

However, shortly after the action, Charles, Cecil's father, received a letter from Sec Lt R O Jones, of the London Regiment. According to the Western Morning News of 30th September 1916, and the Western Times of 2nd and 3rd October 1916, the letter informed him that:

his younger son Sec Lt C W Odam, was killed on the 16th [sic] inst at the battle of the Somme. The letter states that: "he died whilst very gallantly leading his men into action".

The newspapers also reported that a letter had been received from the Company Commander:

I and the other officers miss him now, for he was certainly one of the most popular officers this battalion ever had. Although he was so young, he made up for it with pluck and grit, and died leading his men. His death was instantaneous and painless".

If taken literally, this suggests that the Company Commander, Lt Col Mildren, had, by the time the letter was written, received specific information about Cecil's death. Equally, it is also possible that the letter was written in these terms to provide some sort of consolation to Cecil's parents, even though he was still officially "missing".

In January 1917, the London Hospital Gazette published Cecil's obituary, including a similar quotation from the letter sent to his parents from the Company Commander, but giving his date of death as 15th September 1916:

He was killed in action in the battle of the Somme on September 15th "whilst very gallantly leading his men".

We all officers and men deeply regret his death and feel proud of what he has done ..."

I cannot possibly tell you how much I and the other officers miss him now, for he was certainly one of the most popular officers this Battalion has ever had. Although he was so young he made up for it with pluck and grit, and died leading his men.

Not a single officer or man who is left will think of the Somme and not feel the tremendous loss of officers and men who fell, and uppermost in many minds will be the plucky "Boy".

Cecil was indeed a plucky "Boy", dying aged only 19.

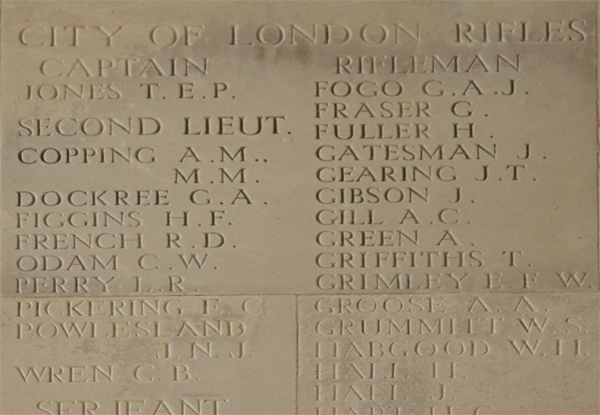

Commemoration

Cecil is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, one of more than 72,000 officers and men who died in the Somme sector before 20th March 1918 and have no known grave.

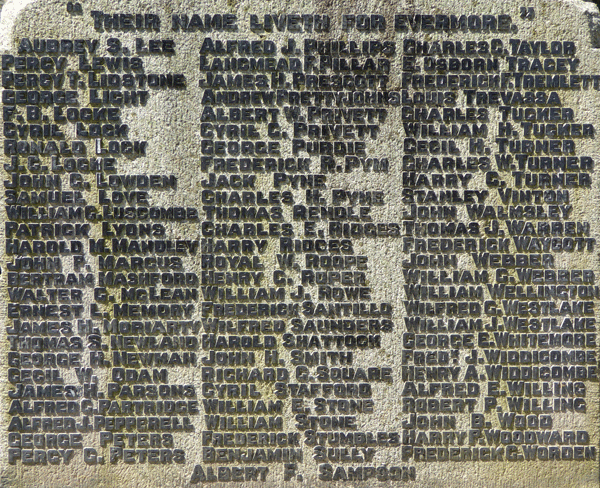

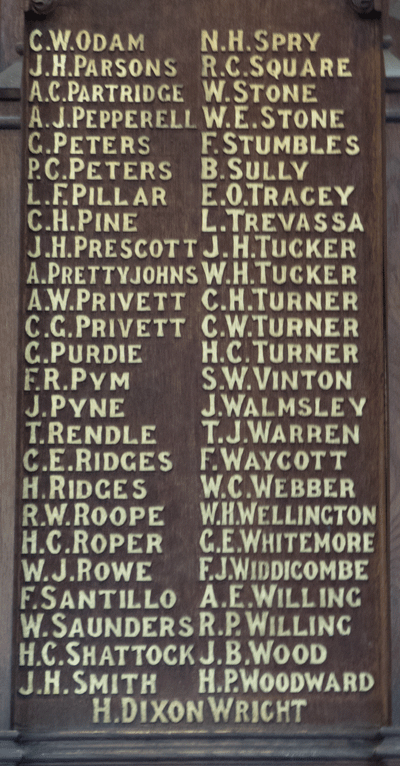

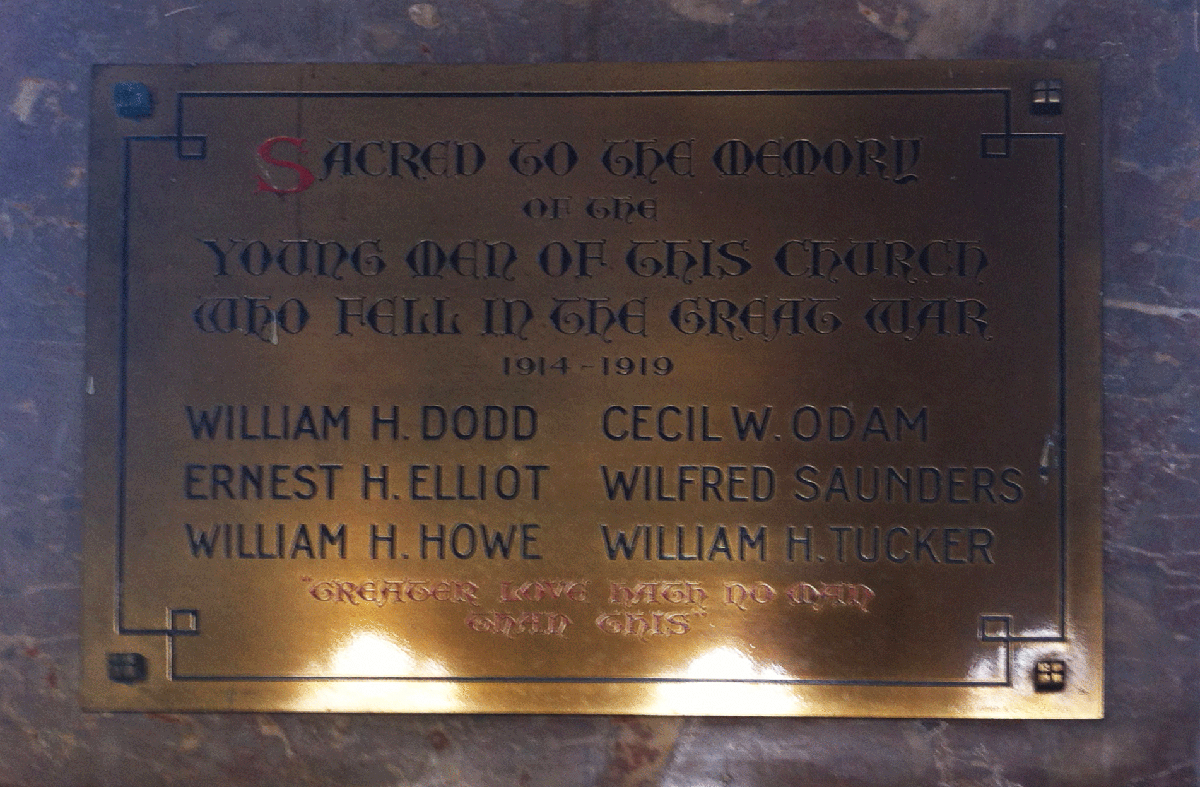

In Dartmouth, he is commemorated on the Town War Memorial, the St Saviour's Memorial Board, and on the War Memorial in the Flavel Church.

He is also commemorated on the War Memorial of the Royal London Hospital; and is listed in the University of London OTC Roll of War Service 1914-1919.

Sources

War Diary of the 1st/6th Battalion London Regiment (City of London Rifles) March 1915 - January 1918, downloadable at the National Archives, fee payable, reference WO 95/2729

The Cast-Iron Sixth: A History of the Sixth Battalion London Regiment (The City of London Rifles), by Captain E G Godfrey, MC, publ 1938 by F S Stapleton

Tanks on the Somme, Imperial War Museums

The Somme, by Peter Hart, publ 2006, Cassell

Somme 1916 A Battlefield Companion, by Gerald Gliddon, publ 2016, The History Press

London Hospital Gazette for 1917 accessed on Meanings of Military Service 1914 website

Memorial of the Royal London Hospital

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Odam |

| Forenames: | Cecil Wilfred |

| Rank: | 2nd Lieutenant |

| Service Number: | |

| Military Unit: | 6th (City of London) bn (Rifles) London Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 15 Sep 1916 |

| Age at Death: | 19 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of the Somme |

| Place of Death: | |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Thiepval Memorial, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | Yes |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |