Thomas Coxon Lidstone

Thomas Coxon Lidstone came from a well-known Dartmouth family. Although he does not appear on any of the town's memorials, his death and burial was reported in some detail in the Dartmouth Chronicle.

The Lidstone Family

Thomas Coxon Lidstone was born on 25th May 1889 and baptised in St Clement's Townstal on 21st July 1889. He was the son of Joseph Parnell Lidstone and his wife Annie Lidstone Coxon, and his family had lived in Dartmouth for over a century.

Thomas' great great great grandfather Joseph Lidstone, a carpenter, was born in Stokenham in 1744. He and his wife Priscilla moved to Dartmouth some time between the baptism of their second child, Reuben, at St Michael's Stokenham, and their third son, Thomas, in March 1770, in the Presbyterian church in Dartmouth. It was Thomas who began to develop a substantial business as a builder, in Dartmouth and elsewhere - for example, he built All Saints Church, Brixham, 1819-1824. Thomas Lidstone senior died in Dartmouth in 1856, having become a freeman of the town.

Thomas Lidstone senior's business was taken on and developed by his son Joseph Lidstone (1796-1865) and grandson, Thomas Lidstone junior, (1821-1888), who became not only builders but also surveyors and architects, most likely learning "on the job", rather than through receiving any formal academic or professional training.

In Dartmouth, Joseph was responsible for improvements to St Petrox, in 1824-1826, and for building the chapel of St Barnabas in 1831. Later, as a "Street Commissioner", he was responsible for planning improvements to the town. In 1844-1849 he was responsible for survey work in connection with the rebuild of St Thomas of Canterbury, Kingswear. Elsewhere, he was involved in designing, surveying, and/or building a number of churches:

Joseph's only son Thomas developed his father's business further and diversified into a number of other business ventures - in the 1869 Post Office directory, for example, his entry reads:

architect, surveyor, builder, undertaker, house and estate agent, statuary, marble, freestone, and monumental mason, steam saw mills (stone and wood), proprietor and insurance agent, wharf and workshops

He continued his father's work on churches, designing the western window and door of St Saviour's in Dartmouth, completed in 1855; restoring Halwell church the same year, improving Stoke Gabriel church between 1854-1856, and restoring Littlehempston church in 1868. In 1868-9 he designed and rebuilt the private Chapel of Waddeton Court, near Stoke Gabriel. In 1871, he became a Diocesan Surveyor for the diocese of Exeter, responsible for overseeing church buildings (living accommodation as well as churches) in the deaneries of Woodleigh, Totnes, Ipplepen and Moreton.

In Dartmouth, he was responsible for undertaking the work to restore Kingswear Castle as a summer residence for Charles Seale Hayne, in 1855; for designing and building the new harbour light, in 1856; for building the telegraph office, in 1857, and later on, for the design of enlargements of the Board School buildings in Higher Street and Newcomen Road. But perhaps the most well-known example of his work is the house he built as a tribute to Thomas Newcomen, the inventor of the atmospheric steam engine, born in Dartmouth in 1664.

Thomas Lidstone had made a proposal in 1851 to erect a monument in St Saviour's Church to Thomas Newcomen and an appeal was published. But insufficient funds were raised so nothing came of it. However, in 1864, Dartmouth Town Council began an improvement scheme to improve north-south communication in the centre of the town with a new road, and integrate into it improvements to the water supply, modern sewerage and new public buildings.

The route of the new street (now called Newcomen Road) required a number of old buildings to be demolished, including Thomas Newcomen's house and workshop, and Thomas Lidstone's firm was one of those involved in the demolition. He decided to construct a house containing items taken from Newcomen's house and from other old houses demolished during the previous 25 years. He purchased land on the western side of Ridge Hill and the house was constructed in 1868.

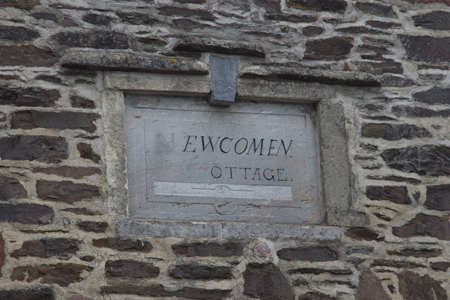

It would appear, however, that Thomas Lidstone made a mistake in identifying which of the houses was Newcomen's. The next-door house was that of Gilbert Staplehill, mayor of Dartmouth in the late 16thC (and a more imposing property). It has been proposed that this property was the source of the carved window frontage used in the house Thomas Lidstone built, rather than Newcomen's house. Be that as it may, the house, called Newcomen Cottage, on Ridge Hill, nonetheless still stands as a memorial to Thomas Newcomen, and indeed, to Thomas Lidstone himself.

The Lidstone business was inherited by Thomas' only son, Joseph Parnell Lidstone, born in Dartmouth in 1850. Joseph began his professional career as an apprentice to his father, but it would seem that he wished to obtain broader experience. By 1874 he was working in London, in the employment of Thomas Clark, an architect and surveyor whose office was at 44 Ludgate Hill; and by 1884, he had secured an appointment in the department of the Surveyor General, Hong Kong.

It may have been his success in obtaining the Hong Kong post that prompted Joseph's marriage to his second cousin, Annie Lidstone Coxon. Annie was descended through her mother, Elizabeth White Lidstone, from Thomas Perring Lidstone, the second son of Thomas Lidstone senior (1770-1856) (put another way, they shared a great grandfather). Elizabeth was the second child and oldest daughter in the large family of Thomas Perring Lidstone, a builder and carpenter, and his wife Elizabeth Ching, who ran a bakery in Higher Street.

Elizabeth White Lidstone had left Dartmouth to work in London, where the 1851 Census recorded her as an assistant in a mourning drapery business in Ludgate Street. While in London she met Robert James Coxon, a bookbinder, whom she married in September 1852. Robert came originally from Northumberland, but - presumably in search of employment - had moved first to Brighton, and then to London. He had married his first wife, Jane Coxon, in Durham in 1838, but over the next thirteen years lost not only her, but also three of their four children.

The tragedy continued. Annie was born in December 1854, and seven weeks later, in January 1855, her father died. Her mother Elizabeth was thus left widowed with a tiny baby and a stepdaughter aged fifteen, and, it would seem, little money. However, she did not go back to her family in Dartmouth, but instead settled in Bothal, Northumberland, with her husband's brother Thomas Coxon, a forester and bailiff to the Duke of Portland. The 1861 Census recorded both her daughter Annie and stepdaughter Sarah living with Thomas Coxon and his wife Mary in Bothal, and Elizabeth once again working in the drapery business, living "over the shop" and working as a saleswoman for a draper in Bishopwearmouth.

Annie thus spent most of her childhood in Northumberland. However, most probably during the late 1870s or early 1880s, she and her mother moved back to London (the 1881 Census recorded them as "visitors" to Thomas and Mary Coxon in Bothal). Her mother, having worked in London herself, may have thought that there would be more opportunity for Annie in the capital than in Northumberland, and so it proved. It is most likely that Annie met her second cousin through the family connection - a connection which had already been reinforced through the marriage in 1878 of Joseph Parnell's sister Ellen to Charles Henry Lidstone, another second cousin and Annie's first cousin - although of course, they might also have met by chance.

In 1883 Annie suffered a double bereavement - her uncle Thomas Coxon in Northumberland in September 1883, and her mother shortly after, at home in Whitechapel. Annie and Joseph married at St Ethelburga Bishopsgate on 2nd June 1884, and they went out to make a new life in Hong Kong.

We know a little about Annie and Joseph's time there because of what subsequently happened to Annie. Joseph became Clerk of the Works in the colonial government of Hong Kong, a fairly significant position. However, both of them caught malaria, and this appears to have damaged their health badly. This may well have influenced their decision to return permanently to England when, in 1888, Joseph's father, Thomas Lidstone, died. Joseph came back to Dartmouth to deal with his father's business. He and Annie settled in a house called "Briny Cot", where Thomas Coxon Lidstone was born the following year, and he set up an office on the new North Embankment, in Dartmouth.

Although Thomas Lidstone had achieved a degree of success in his business career, it seems that he did not leave Joseph and Annie great wealth. Joseph's mother, Emma, had died in 1883 and two years later Thomas had married again. His second wife, Martha Ann Davey, had come to Dartmouth to help her brother James, who ran a grocery store in New Quay, when he was widowed and left with two young children. On Thomas' death, only three years after this second marriage, his estate was divided between his new wife, and his children. He left Martha his house and business premises in Clarence Street, which she sold - she appears to have left Dartmouth thereafter. Joseph was left the remainder of the property owned by his father, including Newcomen Cottage. Newcomen Cottage was also sold, but as his father had taken out a large mortgage on the property, it did not in fact generate much capital. It seems that Joseph felt that London would provide him with more opportunity than Dartmouth to develop his professional career and so, in 1891, Joseph, Annie and Thomas moved back to the city.

But tragedy struck again. On 8th November 1891 Lloyds Weekly Newpaper reported Annie's sudden death, followed by an autopsy, and inquest:

At the Coroner's court, Holloway Road, on Saturday, Dr Danford Thomas held an inquest on the body of Annie Lidstone Lidstone, aged 36, who died at 16 Caledonia Street, Kings Cross, on Wednesday. She was the wife of Joseph Parnell Lidstone, who had for some years been clerk of the works at Hong Kong, China. While there they were both attacked with malaria or native fever. They came to London about a month ago. While out shopping on Tuesday deceased was seized with shivers, and died on Wednesday. The autopsy showed that the organs of the chest were materially affected by malaria, which caused fatal syncope. The jury found a verdict accordingly.

Joseph appears to have abandoned all thought of continuing to live in London and to have returned immediately to Dartmouth. But even there the family resources were limited. Joseph had three sisters - Ellen, Emma, and Elizabeth. But by late 1891 none of them apparently was living in Dartmouth. Ellen and her husband Charles had moved to Montreal, in Canada; Emma, who had been working as a draper's assistant in London's newly developing West End shops, had very recently married Arthur Henry Etherington, a bank manager from Twickenham, and made her home in Surrey; and Elizabeth was unmarried, working away from Dartmouth, perhaps also like her sister in the West End, as a draper's assistant.

It would seem that Joseph and his son Thomas made their home with his aunt Elizabeth Parnell Lidstone, Thomas Lidstone's surviving sister, who had been left well off by her father Joseph Lidstone, with income from properties and investments, as well as inheriting Joseph's own house in Ridge Hill. However, on 10th February 1897, his great aunt Elizabeth died, and was buried in St Clements Townstal on 16th February. Just a week later, Joseph himself followed her, being buried in the same place on 25th February. He died at the age of 46. Thomas Coxon Lidstone was thus left, aged nearly eight, with neither parents nor grandparents.

There seems to be no record of Joseph's will, or even of any letters of administration being sought, which suggests that, whether through illness or some other cause, he may have become completely dependent upon his aunt. Her executor was her niece Emma Etherington. She and her husband Arthur had no children of their own. They took responsibility for Thomas Coxon Lidstone, gave him a home, and arranged his education.

Thomas was sent first to St Anne's Redhill, where he was recorded as a boarder in the 1901 Census, aged 11. This choice of school suggests perhaps that the resources left for his education by Joseph (or his aunt Elizabeth) may have been limited. St Anne's Redhill was a school established by a charity called the Royal Asylum of St Ann's Society, founded in the early 18th century to clothe and educate twelve boys from the parish of St Ann and St Agnes, Aldersgate, in a rented schoolhouse. The objective of the Society was to provide an education, maintenance and a home for children of parents "who have seen better days and moved in a superior station in life" and it was funded by donations and subscriptions. The charity established a "country school" in Lavenham in the late 18th century, which transferred to Peckham in 1794, Streatham in 1829, and Redhill in 1884 (the town school was closed in 1887). In Redhill the school was accommodated in a substantial building on a 20 acre site, with extensive facilities, including a reading room, library, museum, gymnasium, swimming pool and cricket pitch.

In September 1904, aged 15, Thomas entered Bedford Grammar School, now Bedford School, as a boarder. He remained there for four terms, leaving at the end of 1905. Bedford School was, and is, an ancient school refounded in 1552, and, like several other schools in Bedford, a beneficiary in 1566 of the educational endowment of Sir William and Dame Alice Harper. In 1891 the school had moved to its current location just a little outside the centre of Bedford in generous grounds and substantial new buildings.

Having finished his education at 16 1/2, Thomas did not choose his father's, grandfather's and great grandfather's walk of life but instead followed his uncle Arthur into banking. The 1911 Census recorded him aged 21 as a Bank Clerk, living with his uncle and aunt at 1 Montague Road, Richmond, Surrey.

Service

The outbreak of war had prompted an immediate response from a committee of North London businessmen who had decided to raise, uniform and equip an elite battalion accepting only recruits from Public Schools and Universities, to be called "The Public Schools Battalion". Simultaneously Lord Kitchener had appealed, in his "National Call to Arms", for 100,000 volunteers. Before a month had passed, Kitchener was only too pleased to accept offers of assistance of all kinds from local authorities and leading citizens, including initiatives such as that of the North London group. Their battalion was adopted into the Middlesex Regiment and became: "The 16th (Public Schools Battalion) The Middlesex Regiment, The Duke of Cambridge's Own". Recruitment began on 4th September 1914, with advertisements in the London morning and evening papers:

According to his obituary in the Dartmouth Chronicle, Thomas Coxon Lidstone joined the Battalion on its formation, and this is confirmed by his regimental number, PS 473. His qualifications would have been his age, his fitness, and his time at Bedford School, where he may have benefited from some time spent in the OTC. He was at that time working in a London Bank.

The Battalion began its training in October at Kempton Park racecourse. Battalion headquarters, armoury and stores were housed in racecourse buildings and officers, NCOs and men in tents. There was, to begin with, no equipment and no uniform, so they wore civilian clothes and drilled with broomsticks or gas-piping. The men joining came from many different walks of like, notwithstanding the "public school" entry requirement. Over the next few weeks the Battalion lost quite a few recruits, as they applied and were successful in obtaining commissions, and eventually the "public school" requirement was quietly dropped to ensure that the battalion reached, and remained at, full strength.

In January 1915 the Battalion moved to a newly built army camp at Woldingham, on the North Downs in Surrey, though the facilities had been hurriedly built and were far from adequate. There the training continued, though equipment was still very limited, with rifle and bayonet, and in the fast developing techniques of trench warfare. They remained at Woldingham until July 1915, when their next move was to Clipstone Park, Nottingham. It was not until November 1915 that they reached the front line; but Thomas had died several months before that, from meningitis.

The conditions in training camps were recognised at the time as contributing to an upsurge in outbreaks of this disease, especially in the Southern counties of England, following mobilisation and recruitment. These were summarised in an article in the British Medical Journal in late January 1915 as follows:

"In the outbreaks among the troops there have always been three strong disposing factors; overcrowding in camps and barracks; the cold winter weather; and over-muscular exertion among young recruits. Two of these conditions have prevailed in this country during the past three months. The weather has been atrocious, and an enormous number of young recruits have been in active training. One cannot say there has been special overcrowding, but a great many men have been in tents, in the ordinary regulation form of which nine men live in close contact, and ... the ventilation is not always good. It is this very close contact that seems to favour the communication of the disease".

Death

According to the Dartmouth Chronicle, Thomas contracted the disease a week before he died. He was sent home from the camp to his aunt and uncle's house at I Montague Road, Richmond, where he died. The Chronicle of 5th March 1915 reported his funeral as follows:

The funeral took place at Richmond, on Monday last, the first portion of the burial service taking place at St Matthias church and the interment at the cemetery close by. A detachment of his late comrades attended from the camp at Woldingham, while the coffin was covered with the Union Jack.

A large number of floral tokens were received and much sympathy was shown by his friends and those of his relations (Mr and Mrs A H Etherington), with whom he had had a home since the death of his father.

The Chronicle concluded, sadly:

His affectionate and happy disposition endeared him to his many friends among whom his death will be deeply regretted.

Memorials

Though the Chronicle had marked his death in 1915, Thomas' name does not appear on any public memorial in Dartmouth, presumably because there was no longer any member of his close family living in the town.

He is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Richmond Cemetery, where he was buried, and on the Richmond War Memorial.

Sources

Archives of the Incorporated Church Building Society, available online through the Church Plans Online project

Some Account of the Residence of the Inventor of the Steam Engine, by Thomas Lidstone, of Dartmouth, publ Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1869. Downloadable free from Google Books

The Newcomen Memorials in Dartmouth, by Ivor H Smart, available for download without charge from the Dartmouth History Research Group

The Newcomen Road, by Ivor H Smart, available for download without charge from the Dartmouth History Research Group

Thomas Newcomen of Dartmouth and the Engine that Changed the World by Eric Preston, published by Dartmouth & Kingswear Society and Dartmouth History Research Group, 2012

The Royal Asylum of St Ann's Society Redhill, administrative history, Surrey History Centre, Woking

The Public Schools Battalion in the Great War, by Steve Hurst, published by Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2007

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Lidstone |

| Forenames: | Thomas Coxon |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | PS473 |

| Military Unit: | 16th (Public Schools Battalion) Middlesex Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 25 Feb 1915 |

| Age at Death: | 25 |

| Cause of Death: | Disease: Meningitis |

| Action Resulting in Death: | |

| Place of Death: | 1 Montague Road, Richmond, Surrey |

| Place of Burial: | Richmond Cemetery, Surrey |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | No |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Dartmouth Chronicle Obituary, Richmond War Memorial |