George Henry King

Family

George Henry King was born in Dartmouth in 1876 and baptised at St Saviour's on 28th February 1877, along with his elder brother Thomas Henry. George was the second child of Henry King, shipwright, and his wife Ella (or Ellen) Elizabeth Towell.

Henry King had come to Dartmouth as a child from Charleton, near Kingsbridge. At the time of the 1851 Census, when Henry was 11, his mother Jemima was the Toll Gate Keeper at Turnpike House (situated at the junction of Old Mill Lane and the present Townstal Road), near St Clement's church in Townstal. His father Henry King senior worked as an agricultural labourer and later, as a boatman. Jemima died in 1860 and Henry (senior) married again, to Jane Smith, from Dartmouth, in 1863. In 1871, Henry senior, Jane, and Henry junior lived down the hill from the Turnpike, at Coombe. Henry senior was a Boatman and Henry junior a Ship's Carpenter; Jane worked as a charwoman.

In 1874 Henry married Ella Elizabeth Towell, born in Brixham in 1855, the daughter of Elizabeth Ann and Thomas Worth Towell, mariner. Henry and Ella Elizabeth had five children: Thomas, born in 1875; George, in 1876; Jemima, in 1879, William in 1881 (two weeks old at the time of the 1881 Census); and Henry in 1883. The 1881 Census recorded the family living in Clarence St, Dartmouth. However, sometime before Henry's birth in 1883 they moved to Brixham, closer to Ella's family.

It seems that Ella died soon after this, though we have not been able to trace her death for certain. She was not shown with the family in the 1891 Census. Henry and the two youngest children lived at one of three cottages at Brownstone, Boohay, between Kingswear and Brixham, where he worked as an agricultural labourer. George, aged 13, lived close by at Higher Brownstone farmhouse, where he was one of four farm servants employed on the farm run by Thomas Bulley and his wife Mary. Henry had been able to find a place for Jemima at St Faith's Home for Girls in Torquay, where she was one of fourteen girls between the ages of six and fifteen. We have not been able to locate Thomas in 1891, though by 1901 he was living in Paignton and working as a building labourer.

Henry died in 1898 and was buried at Brixham St Mary on 23rd January. By 1901 George had moved back to Dartmouth, where he lodged with John and Sarah Hutchings in Crowthers Hill. George worked as a general labourer and John Hutchings also did labouring work. He and Sarah had come to Dartmouth from Stoke Fleming; in 1891 they lived at New Barn Farm, Norton. By 1901 their surviving children were Florence, born 1882; Walter, born 1886; Mary Ann, born 1888; Hilda and Charles, born in 1894; and Harry Reginald, born in 1898 (he died later in 1901). Also lodging with the Hutchings family was William John Waycott, from Paignton, and also a general labourer.

It seems that both lodgers became part of the Hutchings family. William Waycott married Florence in 1902; and in 1911 George was still lodging with John and Sarah, and those of their children still living at home. By 1911 the Hutchings, including George, had moved to 4 Galpine Terrace, Browns Hill. At that time George was working as a quarryman.

However, fairly soon after this, George decided to move to Swansea, where he found work as a shipwright, his father's trade. But he did not cut his ties with Dartmouth or the Hutchings. On 28th August 1914, very soon after the outbreak of war, he returned to Dartmouth to marry Mary Ann Hutchings, John and Sarah Hutchings' second daughter, known in the family as Annie. Florence Waycott was one of the witnesses at the wedding. Annie, aged 26, already had a daughter, Dorothy Winifred May, born in 1908.

Service

George's wartime service records are among the small percentage that have survived, so we know that he took the medical examination on 30th October 1914 and attested in Swansea on 1st December 1914. He joined the "Swansea Battalion" (the 14th Battalion Welsh Regiment).

In September 1914, the War Office had agreed to the proposal made by the Mayor of Swansea, supported by other prominent local people, that Swansea should form a battalion of the Welsh Regiment, to be recruited from the town and district - a Pals battalion. Following various large meetings to raise financial support for the city's endeavour, on 6th October 1914 the following advertisement was placed in the South Wales Daily Post:

Recruits for the above Battalion are now being enlisted at Mond Buildings, Union Street, Swansea ...

Upon being medically passed and attested each man becomes entitled to 1s per day pay and, until he is billeted and lodged and maintained in a public building, he will receive besides 2s per day ...

Note - a few experienced NCOs are urgently required.

George's decision to enlist was clearly not immediate, and this perhaps is the reason he enlisted in Swansea, rather than in Dartmouth. (Charlie Hutchings, Annie's younger brother, had joined the Devonshire Regiment only three days after George and Annie were married - see below). George presumably went back to work in Swansea after his marriage and whatever honeymoon he and Annie could afford, and then found himself subjected to the full force of appeals to enlist. Perhaps he joined up with others from his workplace (his papers do not provide any information about where he worked - he described his "trade or calling" at the time he attested as "labourer").

In taking time to respond to the recruiting drive, he was not alone. Recruitment to the Swansea Battalion was a bit slow - by 24th November numbers were up to almost 950, but to sustain a Battalion of around 1000 men in the field for any sizeable period of operations, something like 1300 recruits were needed. George was 4 months over the maximum age, but, according to his attestation record, had previously served in the Devonshire Militia. Presumably this military experience counted in his favour, not to mention the need to find sufficient recruits for the Battalion. There are no details in his papers about when, or how long, he served with the volunteers in Devon (and no papers appear to have survived for this service).

We know however that he was one inch above the minimum height, with blue eyes and dark hair, physically fit, but with "bad teeth". He stated that he was married, with one child (Annie's daughter Dorothy) - entitling Annie to a separation allowance of 15s per week.

The day after George attested, the Swansea Pals joined other Battalions of the Welsh Regiment training at Rhyl. Like many Kitchener Battalions, they were short of everything - uniforms, boots, tents, weapons, ammunition, and also regular officers with up to date military experience. On 29th April 1915, the Battalion was allocated to the 114th Brigade in the 38th (Welsh) Division, with Major General Ivor Phillips in command. Ivor Phillips had left the Army ten years earlier, having served in Burma, on the North-West Frontier, and in China. He had been a Liberal MP (for Southampton) since 1906.

At the beginning of September 1915, the Battalion left Rhyl for Winchester, to begin training as part of the 38th Division. There they finally were fully equipped with rifles and other necessaries, and began their military training in earnest. In the meantime, Annie had given birth to a boy on 25th May 1915, whom she named George Henry King. She and her children continued to live with her parents at 4 Galpine Terrace, Browns Hill.

On 29th November 1915, the Division was reviewed by the Queen, the King being ill, and on 2nd December, the Battalion left Winchester at 5.15am for Southampton and Le Havre. They arrived in the front line at Richebourg, between Armentières and La Bassée, and received their introduction to life in the trenches from the Guards Division.

The Battalion was in the front line on Christmas Day (and sustained its first casualty) but Swansea Corporation sent 1000 plum puddings, as well as sending each man a writing pad, fifty envelopes and a pencil (though the gifts did not arrive until 2nd January). They were not involved in any heavy fighting, but as they followed the usual routine of periods in the trenches, followed by "rest periods" whilst providing working parties to assist elsewhere in the front line, followed by time further back from the front line in reserve, casualties began to mount. Writing home at the beginning of March 1916, a member of "D" Company - George's company - said that they had been in the trenches for ten days without taking their boots off once.

When they went back into the front line at Givenchy, a little further south, they suffered losses every day between 12-15 March. During April, casualties were very light, but during May, when the Battalion was in the front line at Laventie (still between Armentières and La Bassée) they lost:

- three men killed and 11 men wounded on 1st May, with one officer wounded who subsequently died;

- one officer and 3 men wounded on 6th May;

- one man killed and one wounded on 7th May;

- two men wounded on 18th May;

- one man killed and one wounded on 19th May;

- one man killed and two wounded on 20th May;

- one officer wounded whilst they were in support on 21st May;

- one man killed and one wounded on 26th May;

- two men wounded on 27th May;

- one man killed and one wounded on 28th May;

- one man killed and one wounded while the Battalion was being relieved on 29th May.

The War Diary provides no further details. George's service papers show that he went to hospital in the field on 4th May, leaving the following day, but do not give the cause. There is no mention of him being wounded.

On the night of 4th June, the Battalion was involved in a trench raid. Twenty men, in two teams of nine each under an officer, carried out a bombing raid (that is, with grenades) on the German trenches at 11pm. The team on the right, led by Lt Wilson, killed five, but the team on the left, led by Lt Corker (the son of the Mayor of Swansea) came into immediate contact with the enemy, who bombed back. After a hasty withdrawal, Lt Corker and one member of his team were missing, one man was killed, and seven were wounded, one of whom died of his wounds. The following night, Lt Strange and two men went on a search party for Lt Corker and the other missing member of his team, but failed to find them; one of the search party was wounded by heavy machine gun fire and died. Subsequently it was determined that Lt Corker had been slightly wounded in the raid itself, but was killed while attempting to get back to the British lines. Lt Strange was subsequently awarded the Military Cross for his part in the raid and for his attempt to find the two missing men.

The Battalion then spent a few days in reserve, followed by two weeks in divisional training, before beginning its move south to arrive on the Somme. During this period, George had ten days of leave to England from 4th - 14th June, providing him with his first (and as it turned out, only) chance to see his little boy, who had just turned one year old, and of course Annie and her daughter and the rest of the Hutchings family.

On 1st July 1916, as the great attack began, the Battalion arrived at Herissart, north east of Amiens (they were not involved in the fighting). On 5th July, they received orders that 38th (Welsh) Division would relieve 7th Division, north of Fricourt and Mametz. This sector of the line had seen the only successes on 1st July (see the stories of Robert Phillips Willing and Jack Butteris).

The Attack

The next phase of the Somme offensive was to push forward the attack in the south, to attempt to break through the German Second Line. In addition, there were to be diversionary attacks to the north. Prior to the main attack in the south, preliminary attacks were made on several targets, with the overall aim of securing the northern flank of the main attack to the south which had been scheduled for 14th July.

The 38th Division was to attack Mametz Wood, north of the village of Mametz. The first to attempt the task on 7th July were the 16th Welsh and the 11th South Wales Borderers. In Peter Hart's words: "this was to be the first of a series that would indelibly mark out a link between the pride of Wales and this hitherto obscure little French wood". They were cut to ribbons by heavy fire from well-placed machine gun positions to the rear of the wood, which had not been affected by British shelling of the wood itself. The attack was called off.

While this was underway, the Swansea Battalion was in support, at the Citadel, a position south of Fricourt, training for the attack. In the afternoon, several officers were practising throwing percussion bombs, undetonated bombs being used. One exploded, and four officers were accidentally wounded.

On 8th July, the Battalion moved into the front line in White Trench, south of Mametz Wood. The position may be seen here.

That day, 17th Division, next to the left of 38th Division, made two further attacks on the wood, but was also driven back. In 38th Division's own sector, meanwhile, there was confusion between plans at Corps level for a small scale raid, and plans at Brigade level for a larger-scale attack. Consequently no attack took place and Generals Haig and Rawlinson relieved Major General Phillips of his command (and also the commanding officer of the 17th Division). Command of 38th Division passed temporarily to Major General Watts, of 7th Division, who decided that the Welsh Division would attack Mametz Wood on 10th July "with a view to capturing the whole of it". 113th and 114th Brigade, including the Swansea Battalion, would attack together - the hope being that the defence would be overwhelmed by sheer weight of numbers, as well as by a preliminary bombardment.

The Swansea Battalion spent 9th July in White Trench preparing for the attack. The plan put 114th Brigade on the right and 113th Brigade on the left, with the Swansea Battalion to the left of 114th. Within the Battalion, "B" Company was on the right; "C" Company on the left; "A" company in support and "D" Company, including George, in reserve. There was some careful instruction about the compass direction of the advance, since once inside the wood it was easy to lose sense of direction. They were to follow behind the artillery barrage as closely as possible as it moved forward, and were told that artillery would sound much louder in the wood than outside it. All units were ordered to carry cutting tools because of the tangle of vegetation (and worse) within the wood. The expectation was of heavy losses - Lt Col Hayes, the Swansea Battalion's commanding officer, was remembered as saying:

"Tomorrow at five minutes past four our battalion is going to take that wood but - we shall lose our battalion".

The War Diary describes the ground to be crossed, which had been reconnoitred by Lts Strange and Yorke: "It went about 300 yards on the level, then down a steep cliff, about 30 feet deep, with paths in various places, then up a gradual rise to the edge of the wood".

At 3.00am on the morning of 10th July all were in position and the artillery bombardment began; at 4.05am "B" and "C" Companies of the Swansea Battalion began their advance.

The War Diary reported that:

The advance was made in quick time and from 80-100 yards distance between the waves ... in perfect order ... The casualties were very slight until the edge of the wood was reached ... when the wood was entered it was found to be very thick and owing to the intense bombardment was most difficult to penetrate. The sides were almost indistinguishable [from within] and it was difficult to keep direction.

One of those who was there, Sergeant Dick Lyons of "D" Company, recalled things a bit differently:

Machine gun and rifle fire was trained on us ... We suffered a great many casualties particularly among our officers. The Germans were adept at picking them off. When we reached their positions we escaped a good deal of the gunfire in No Mans Land. They would not fire on their own positions for fear of killing their own men, but they were still firing over our heads whilst our guns were also firing over our heads on to German targets. Many of the shells ... hit the trees above us, detonated, and caused us more casualties.

Accounts of the attack state that within the wood there was intense hand-to-hand fighting. Lt Wilson, leading "D" Company (which must have been brought into the fight fairly soon after the initial advance) was seen to bayonet a "burly German" and to bring down a shot sniper in a tree.

As the men struggled through the wood units became intermixed. At 10.30am Lt Col Hayes of the Swansea Battalion was placed in command of all 114 Brigade troops in the wood and was ordered to push on to the second objective. Command of the Swansea Battalion passed to Lt Strange. The War Diary's account of the action is rather light on detail, but it does say that "the enemy was cleverly concealed in pits and they used their machine guns with skill" and "the men were highly tried". Nonetheless "the advance was carried out to the Northern edge of the wood" and alongside the Swansea Battalion, the 13th Battalion Welsh Regiment also got through the wood to the northern edge, once all 114th Brigade's reinforcements were thrown into the fight. But all attempts to drive the enemy completely out of the wood were thwarted by heavy machine gun fire coming from positions outside the wood.

At 1.0am on 11th July, according to the War Diary, Lt Col Hayes brought the Swansea Battalion out of action. Intense fighting by other Battalions in the 38th Division continued until the wood was finally secured on 12th July, but the Swansea Battalion played no further part in this. Those that emerged were given the opportunity to rest briefly back at the Citadel, south of Fricourt, before marching to billets.

Death

The Battalion had lost over 90 men killed and almost 300 wounded; by the end of the action, the 38th Division overall suffered casualties (killed and wounded) amounting to 190 officers and 3,803 other ranks. Evidently George was not one of the members of the Battalion brought out of the wood by Lt Col Hayes; his service papers indicate that the circumstances of his death were uncertain.

On 24th July 1916, he was recorded as "wounded in action in the field" on a date expressed as "10/12-7-16" - presumably meaning some time between 10th-12th July 1916.

On 4th August 1916, his records were updated to read "killed in action in the field" on a date still given as "10/12-7-16". A further standard report of his death for War Office use gave the cause as "killed in action" but continued to reflect uncertainty about the date, which was still recorded as "10/12-7-16". The form states that information about his place or date of burial was "not forthcoming" - presumably meaning that no such information had come to light.

The Army continued to be in doubt about the date of his death for some time. George's length of service was calculated to have lasted until 12th July 1916, for purposes of the pension to be paid to Annie. The pension was paid with effect from 19th February 1917. The date of death on his Medal Index Card was also given as 12th July 1916.

However, by the time of the publication of "Soldiers Died in the Great War" in 1920-21, the date of George's death had been determined as 10th July 1916. This is the date shown for his death in Commonwealth War Graves Commission records. CWGC records also show that the body identified as his was first buried in a place with reference 57DX30c34 and then reburied in Danzig Alley Cemetery, near the village of Mametz. Following the reburial, the Welsh Regiment was asked in 1925 to confirm that George had died on 10th July 1916 and, from the papers in George's file, evidently did so.

The accounts of the Battalion's action indicate that it is most likely that George was killed in action in the battle for Mametz Wood on 10th July 1916 - or, if he was not killed outright, that he died very soon afterwards of wounds he sustained in that action. Our database therefore records him as killed in action on 10th July 1916.

Commemoration

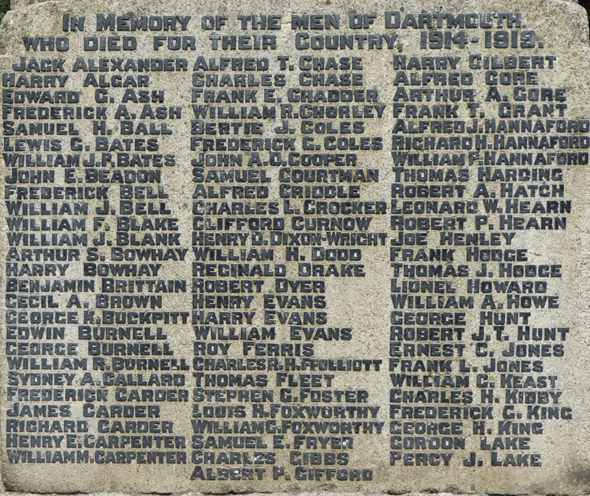

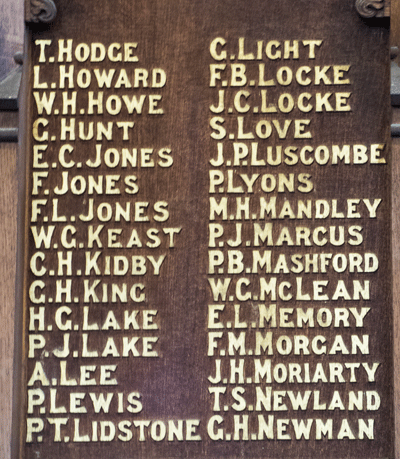

George is commemorated in Dartmouth on the Town War Memorial and the St Saviour's Memorial Board.

Bernard Lewis, in his history of the Swansea Pals (to which the above account is indebted), observes that "The one day [the Battalion] spent fighting in the wood was undoubtedly a defining moment in the history of both the Battalion and, indeed, the town of Swansea". Swansea observed 10th July as "Mametz Memorial Day" until the outbreak of the Second World War.

The attack of the 38th Division on Mametz Wood is now commemorated nearby by the Welsh dragon memorial, inaugurated on 1st July 1987.

Charles Edward Hutchings

Soon after the outbreak of war, Annie's younger brother Charles enlisted in the Devonshire Regiment, on 31st August 1914, joining the 2nd Battalion. Some time during the early part of 1915, Charlie, as he was known, was seriously wounded, most probably during the 2nd Devons attack at Neuve Chapelle, on 10th-12th March. The following piece appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle on April 16th 1915:

A gallant young Dartmouth soldier, Private Charlie Hutchings, 2nd Battalion Devon Regiment, son of Mr and Mrs Hutchings of 4 Galpine Terrace Browns Hill, has sustained serious wounds during an engagement in France and is now a patient at No 7 Stationary Hospital Boulogne. Private Hutchings was wounded in his left arm, which it has unfortuantely been found necessary to amputate; his right leg was broken and wounded in seven places, and he also sustained a large wound on the left leg ... A nursing sister writes of Private Hutchings that he is bearing his suffering with much patience, is quite a favourite with them, and seems wonderfully cheerful. His recovery is not yet far enough advanced for him to be sent to England.

Charlie returned to Dartmouth on 9th July 1915. He was honourably discharged from the Regiment on 14th February 1917 and issued with a Silver War Badge on 21st March 1916.

It seems appropriate to remember his sacrifice also, so he is included here.

Walter John Hutchings

Another of Annie's brothers, Walter, had joined the Royal Navy as a Stoker on 24th January 1908. He joined HMS Centurion on 22nd May 1913 and was still serving in her at the outbreak of war. He was appointed Leading Stoker on 1st April 1915 and left the ship on 8th March 1918, so in all likelihood participated in the Battle of Jutland. He survived the war and was demobilised in 1920.

Sources

Soldier's Documents WO 363 George Henry King accessed on subscription website

The War Diary of the 14th Battalion Welsh Regiment is available for download (fee payable) from the National Archives, reference WO 95/2559/3

Swansea Pals, A History of 14th (Service) Battalion, Welsh Regiment in the Great War, by Bernard Lewis, Pen & Sword Books, 2005 (ebook format)

The Somme, by Peter Hart, publ Cassell, 2006

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | King |

| Forenames: | George Henry |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 18026 |

| Military Unit: | 14th Bn Welsh Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 10 Jul 1916 |

| Age at Death: | 39 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of the Somme |

| Place of Death: | Near Mametz, France |

| Place of Burial: | Dantzig Alley Cemetery, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |