Charles Henry Kidby

Family

Charles Henry Kidby was born in Winchester, Hampshire, in 1899. He was the elder of two sons of Henry Kidby and his wife Emily Ann Travers.

Henry and Emily married on 21st April 1898 in the parish church of Melcombe Regis, on the north side of Weymouth harbour. Emily came originally from the little village of Loders, near Bridport but by the time of the 1891 Census was working as a "nurse" in Melcombe, in the household of John Laws, a dental surgeon. Henry, a cooper, was born in Colchester, but had moved with his family to Weymouth, on the south side of the harbour, by 1891. Electoral registers and other records show that Henry lived with his mother, Mary Ann Kidby, at 6 Corney Terrace, Westham, Weymouth until 1897.

By the time of his marriage, Henry had moved to Winchester, where he worked as a cooper in a brewery; so Winchester was where the couple first settled. Charles and his younger brother Reginald John were born in Winchester in 1899 and 1900 respectively, and the 1901 Census recorded Henry, Emily and Charles living at 11 Middlebrook Street. However, Reginald, aged only one, was not at home because he was ill - he is shown amongst the patients in the Royal Hampshire County Hospital.

Electoral registers then show Henry Kidby once again living at 6 Corney Terrace, Weymouth in 1901 and 1902, his mother's house. It is not clear whether Emily Ann and the two children also lived there. By 1905, Henry had moved to Hudson Road, Burnham on Sea, and by April 1907, at the time of the death of his brother Jonas, Henry and his mother were living at the Exchange Inn, Puriton, in Somerset, where Henry was the licensee. Henry's mother died later that year. How long Henry remained in Puriton is not clear.

At the time of the 1911 Census, Emily and her two boys, Charles and Reginald, lived at 6 Albion Crescent, Portland, in Dorset. Emily was described on the census form as married, but also as the head of the household. She ran a lodging house; on the night of the Census there were two, a surveyor and a bank clerk. Charles and Reginald, aged 12 and 11, were both at school. Henry's absence from the Census would appear to be explained by passenger records which show that he travelled to New York in June 1910 and came back a little over a year later, on 30th July 1911. Perhaps he had decided to emigrate, but then changed his mind.

When Emily and her sons came to live in Dartmouth is not clear, but they were resident in the town by the time that Charles joined the Army. Both Charles and Emily Ann were recorded in the 1918 Electoral register, at 3 Highland Terrace (Higher), South Town; the following year, Emily Ann moved to 9 Nelson Steps. No information has come to light about Charles' line of work.

Service

Charles' service papers have not survived but, following the introduction of conscription, he would have been called up around, or soon after, his eighteenth birthday, early in 1917. The surviving papers of men with service numbers close to Charles in the Royal Berkshire Regiment suggest that he joined the 93rd Battalion of the Training Reserve for his basic training, based at Chisledon, Wiltshire. The Training Reserve was formed in September 1916 to handle the large numbers of men coming into the Army after conscription. The Reserve absorbed the reserve battalions of infantry regiments but within it there were no regimental distinctions.

The Training Reserve was remodelled in 1917 into four different types of unit, based around the soldiers' age. The 93rd Battalion became the 262nd Infantry Battalion and then, after another reorganisation, when training battalions were realigned with specific regiments, the 51st Graduated Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. However, Charles did not join the Warwickshires - it seems likely that Charles was part of a contingent posted from the 51st Graduated Battalion (Royal Warwickshire Regiment) to the Royal Berkshire Regiment on 2nd April 1918. They were sent to France the same day, joining the 2nd Battalion only a few days later.

The 2nd Battalion, a regular army unit, was in India at the outbreak of war and was brought back to join the 8th Division, in the 25th Brigade, going to France in November 1914 and remaining on the Western Front.

In March 1918, the 2nd Battalion sustained heavy casualties during the first phase of the German spring offensive, attempting first to hold a line of defence on the Somme river, and then becoming part of the rapid retreat towards Amiens. On 1st April 1918, they were relieved by the French near Thennes, south-east of Amiens and by 5th April, had reached billets in Le Quesnoy. Here their War Diary records that they were joined by large drafts of reinforcements, 389 on 5th April and 168 on 9th April. It appears likely that this included Charles.

On 13th April, the 2nd Battalion moved to Lamotte Brebiere, where thirteen new officers joined. At this point the Division was imminently expecting to be sent north as the second phase of the German offensive developed; but after frequent changes of orders, remained in the South near Amiens. The 2nd Battalion went back into the line near Villers Bretonneux on 20th April, in support positions to the rear of the village, west and north.

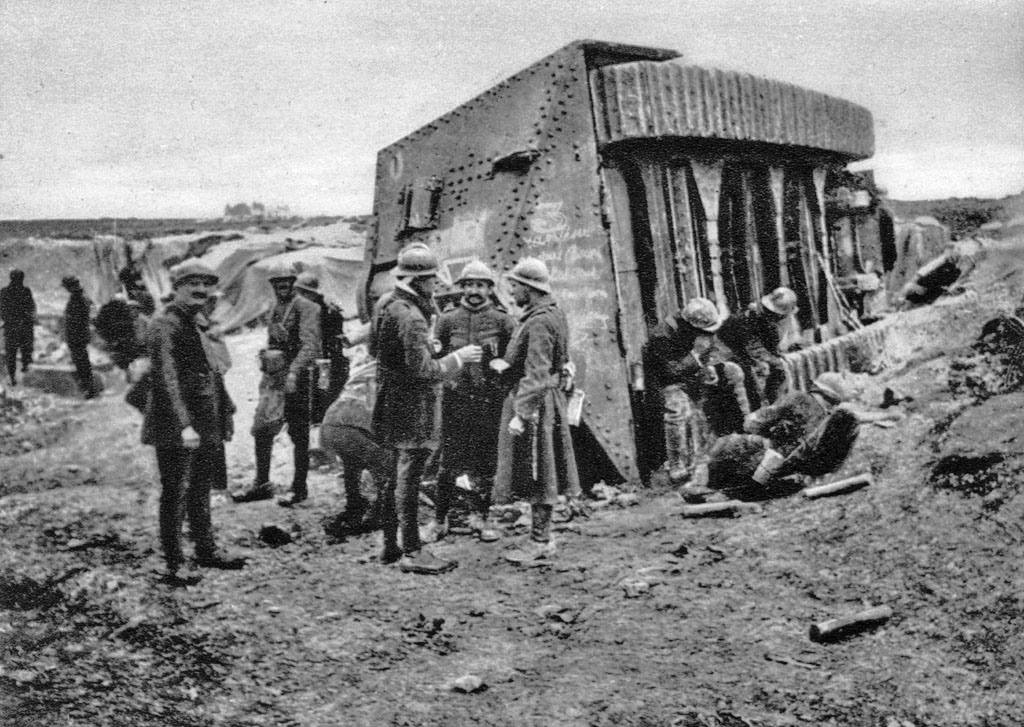

On 24th April the Germans renewed their attempt to take Amiens and attacked at Villers-Bretonneux. The War Diary appears to have no account of the attack, but the 8th Division's history describes "the heaviest bombardment that the division had yet experienced [which] lasted at its fullest intensity for more than two hours … all units had already suffered very heavy casualties from the German bombardment when at about 6.30am the enemy began to put down smoke all along the front". The German attack included three tanks and overwhelmed the battalions on the right of the Division's front. By mid-morning the Germans had taken the village and the Royal Berkshires formed the major part of a "containing line" to the west.

At this point British tanks came into action, in what Peter Hart describes as "a historic moment pregnant with possibilities for both sides … presa[ging] much of the future of armoured warfare" as they clashed with the German tanks. The 8th Division's history states that "all German tanks encountered were put out of action or driven to retreat".

Further advance was prevented and that evening a counter-attack involving three brigades, two of them Australian, began. Two 8th Division battalions were allotted to the two Australian brigades and the rest of the 8th Division, including the 2nd Royal Berkshires, held the reserve lines.

The counter-attack met heavy resistance but, in a hard fight, succeeded in breaking through, though not quite in completely clearing the village. The 2nd Royal Berkshires were thus moved into the attack at 6.30am on 25th April and, according to the 8th Division's history, "advancing with great dash they soon made their presence felt". By midday the village had been cleared and by dusk the front was secure. The 2nd Royal Berkshires' War Diary, however, has no detailed account of the action, only recording briefly "village cleared and mopped up and 36 machine guns and 300 prisoners captured". They came out of the line overnight on 27th April; Charles' role in his first battle is unknown but evidently he survived it. The 2nd Royal Berkshires recorded a total of 260 casualties:

Officers: one killed, nine wounded, two of whom later died

Men: killed 55; wounded 166; gassed 19; missing 10

The 8th Division's history comments that, at this point:

a period of rest, recuperation and reorganisation was essential for once again the division had suffered very severely. Hardly in fact had the wastage of the March battle been made good, the necessary reinforcements received and the work of assimilation commenced, when they had again been consumed in the furnace of battle.

The 8th Division was thus one of those transferred south to form part of IX Corps, attached to the Sixth French Army, between Soissons and Reims, at the time a quiet sector. As Peter Hart puts it:

The divisions selected represented a roll-call of pain from the battles they had collectively endured on the Somme and Flanders: the 8th, 21st, 25th and 50th Divisions. They were stuffed full of inexperienced drafts, fresh troops it was true, but lacking the experienced NCOs and officers that could find them together in action.

The plan was that these divisions would relieve French divisions to form a General Reserve for deployment by Field Marshal Foch, now the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, as and when necessary. It was a sensible plan but with a fatal flaw - that the Germans had decided to target this sector for the next phase of their final offensive.

The 2nd Berkshires moved south by train on 5th May and went into the line near Berry-au-Bac on 12th May. According to the 8th Division's history, "as late as 25th the situation was quiet and there seemed to be no indication on our front that anything unusual was contemplated by the enemy".

The situation changed the following day when it became clear that an attack would be launched imminently. The 8th Division held a central position on the IX Corps front, with the 2nd Royal Berkshires to the right of the divisional front, south of the stream called "La Miette", which flowed southwards into the Aisne. The Battalion's sector of the line was problematic - according to a statement made later by Captain Alfred Clare MC (who was taken prisoner in the battle):

Immediately on arrival in this new sector … which was a large salient, the CO, Lt Col J A A Griffin … reported to Bde HQ how impossible the position was, should the Germans make an attack, as they had direct observation of our whole line from Hill 108 on our right, and from rising ground on our left between our left and the Miette stream …

At 1am on 27th May the bombardment began. 5263 German guns were used against the Allies' 1422, the greatest superiority ratio achieved by the Germans in any of their battles during the course of the Great War. Captain Clare's account continued:

The Germans launched their attack at 1am on 27/5/18 by dropping a tremendous barrage, covering the ground from Bn HQ and including our two rear companies (one in close support and one in reserve) and then back to and including the Divisional Artillery and the Aisne bridges. Our two forward Companies were almost untouched. We were defending in depth as well as breadth. About 3.30am reports came in from our rear Companies that Germans were all around them in very large numbers, and had attacked from Hill 108 and from our left. This we soon confirmed as Germans were visible from Bn Observation Post in large numbers, and had overcome our forward Companies by excess of trench mortars and machine guns. Under such circumstances with no artillery support, chances of a scrap were absolutely useless. Orders were given by our CO for "every man for himself" and he, I and others of Bn HQ on the chance of a counter attack by the Bn in support at Guyencourt. A pigeon message was sent to Division about 4am stating the position … I was captured with Colonel Griffin at 7am ..

The 8th Division history observes:

Nearly all the outpost units were cut off to a man … it is difficult to reconstruct precisely the sequence of events. It is only at intervals that a clear message comes back out of the chaos and confusion …

One such was the pigeon's, which, perhaps surprisingly in the chaos, arrived at Division. The 8th Division's history times it at 5.15am; it was later given to war correspondents and appeared in many newspapers in July 1918:

Germans threw bombs down dug-out and passed on. Appear to approach from right in considerable strength. No idea what has happened elsewhere. Holding out in hopes of relief.

No such relief was possible - the Forward Zone was overwhelmed all along the British front. Only remnants of the 8th Division succeeded in crossing the river. The attack continued over the next three days at an unprecedented rate but gradually became overextended and finally the pace slackened on 31st May.

The War Diary of the 2nd Royal Berkshires states, for the dates of 28th-31st May, that "Battalion took part in Operations between these dates", listing briefly that on 27th/28th, one officer and 60 men "took up a position due south of Ventelay"; and on 29th, another officer with 68 men "composed of stragglers" "took up a position in front of Sarcy"; as the desperate fighting continued. But it is clear from all available accounts that there was no Battalion in any sense as a fighting unit. On 1st June, the "bayonet" strength was seven officers and 120 men; and the "estimated casualties" recorded for up to that date in the War Diary for the period were 23 officers and 600 men.

All the other battalions of the 8th Division were in a similar state, so the division was formed into a composite battalion, under the command of 19th Division. The composite battalion held part of the new Allied Line until the night of 11th/12th June, when it was withdrawn; the British troops left the French sector the following day.

Death

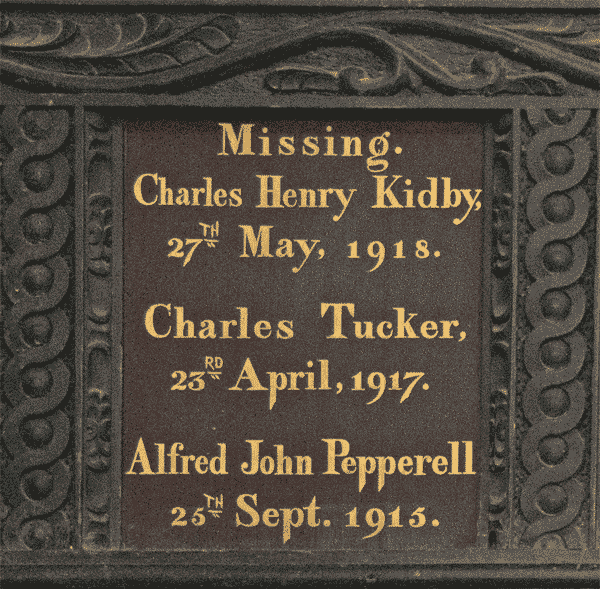

What happened to Charles is not known. He was first recorded in casualty lists as "missing" (Western Times, 31st July 1918).

The Register of Soldiers Effects recorded his death as "presumed 27th May - 11th June"; Soldiers Died in the Great War gave his date of death as 11th June, and this was also the date used by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

On the St Petrox memorial, however, he is shown as "Missing", with a date of 27th May 1918, the first day of the Battle of the Aisne. We have used this date on our database as it would appear to be the mostly likely date for Charles' death.

Charles was nineteen years old.

Commemoration

Whatever the circumstances of his death, Charles' body was never found, or identified, so he has no known grave. He is commemorated on the Soissons Memorial, on which is inscribed:

When the French Armies held and drove back the Enemy from the Aisne and the Marne between May and July 1918, the 8th, 15th, 19th, 21st, 25th, 34th, 50th, 51st and 62nd Divisions of the British Armies served in the Line with them and shared the common sacrifice. Here are recorded the names of 3987 officers and men of those divisions to whom the fortune of war denied the known and honoured burial given to their comrades in death.

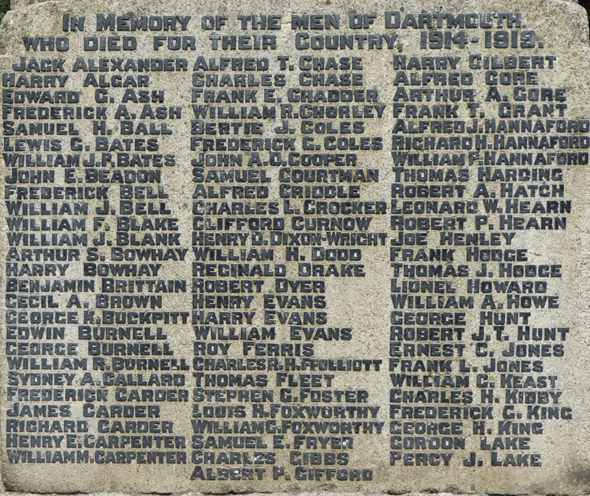

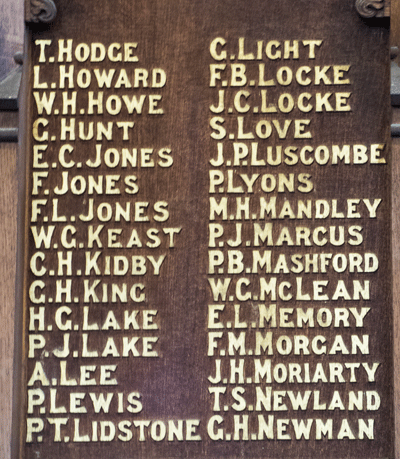

In Dartmouth, Charles is commemorated on the Town War Memorial, the St Saviours Memorial Board, and, as mentioned above, on the St Petrox Memorial.