William Henry Howe

William Henry Howe's story provides an insight into the experience of those fighting in the campaigns of the first few weeks of the war.

Family

William Henry Howe, sometimes called Henry or Harry, was born in 1889 in Stonehouse, one of the "Three Towns" now amalgamated within modern Plymouth, Devon. His father, George Howe, was also born in Stonehouse (according to Census records). According to National Archive records, George had joined the Royal Marines aged 12. In the 1871 Census he was recorded as a Corporal, Royal Marines, in the Royal Marine Barracks in Stonehouse.

In 1877 George Howe married Susan Lane, born in Kingsbridge in 1852, at St Matthew's, Stonehouse, Plymouth; she seems to have followed the flag, as the 1881 Census recorded them both lodging at 15 Moss Street, Paisley, Scotland. By this stage he had reached the rank of Sergeant in the Royal Marines. National Archive records state that he was discharged the following year, in 1882, "as an invalid".

After his discharge, George and Susan made their home in Plymouth. They had three children. On 20th June 1889 all three boys were baptised at Holy Trinity and St Saviour's Plymouth. George junior was seven, born on 17th February 1882; Frank was five, born on 18th June 1884; and William Henry was the baby of the family, at thirteen months, born on 9th May 1889. At that time the family were living at 2 Battery Street, Stonehouse, very close to the Royal Marine Barracks. George was recorded as a "pensioner", presumably as he was receiving a Royal Marine pension; however, by the time of the 1891 Census, he was working as a storeman.

At some time between 1891 and 1901 the family moved to Dartmouth, where in 1901 they lived next door to The Floating Bridge. At that time, George was working as a General Labourer. Nothing is recorded for William Henry's occupation, but he was presumably at school as he was 11. His elder brother Frank was a tailor's apprentice in Dartmouth. There does not seem to be any record of the eldest brother George.

Service

It would seem that William Henry first joined the Royal Navy, as there is a RN Seaman's record in the name of William Henry Howe, born Stonehouse, Devon, 3rd May 1887 - though if this is "our" William Henry he overstated his age by two years (not uncommon for young men keen to get a job). Assuming this is the right man, he joined HMS Britannia (the Royal Naval College) as a Domestic Third Class, on 4th October 1905, ostensibly aged 18, but in fact aged 16. He became an Officers Steward Third Class on 1st October 1907, but was discharged from the Navy on 20th January 1909 "shore: service no longer required" but nonetheless of "very good" character.

He then joined the Coldstream Guards, enlisting at Devonport, sometime between January 1909 and January 1910 - which ties in with his discharge from the Navy. It seems from the records that in the Coldstream Guards he was known as Henry or Harry Howe.

All the records agree that he was a member of the 3rd Battalion. This had been in Egypt since 1906, but returned to the UK early in 1911. The 1911 Census, taken on Sunday April 2nd, recorded Henry Howe as a private in the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards, aged 21, and single, at the barracks in the Tower of London. Shortly afterwards, all three Battalions lined the streets at the coronation of George V on 22nd June 1911, and later that summer, were on "strike duty" during a national railway strike in August.

Outbreak of War

The Battalion War Diary, together with the Regimental History of the Coldstream Guards for the Great War, gives a vivid account of what its members experienced in the first few weeks of the war. In the summer of 1914 the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards was at Chelsea Barracks. As part of the planning for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), which by then had been underway for some time, all three Coldstream Battalions had been selected to be included - the 1st Battalion formed part of the 1st (Guards) Brigade, and the 2nd and 3rd Battalions formed part of the 4th (Guards) Brigade. Consequently they were all on their way to France a week after the declaration of war.

The 3rd Battalion left Chelsea on the morning of 12th August, the second half being waved off by Queen Alexandra, and by way of Southampton and the "Cawdor Castle" arrived at Le Havre the following day. On the evening of 14th August they went by train towards the planned area of concentration for the BEF around the Franco-Belgian border, near Mons. They arrived at Wassigny the following evening, from where they marched to Grougis, where they rested for four days. Over the next three days they marched to the required position in the front line, in extremely hot weather, and suffering from the effects of inoculations against typhoid fever they had received whilst at Grougis.

Very early on Sunday 23rd August, the 3rd Battalion arrived just behind the front line at Harveng. During the Battle of Mons, which was the first engagement fought by the British Army against the Germans on the Western Front, none of the Coldstream Battalions came into collision with the enemy and there were no casualties. In the afternoon, the 3rd Battalion were first ordered to go back to Quevy Le Petit, through which they had just come, and then back to Harveng. The Battalion War Diary says "on arrival there the utmost confusion seemed to prevail ... no one seemed to know whither to go or what to do" and even the Regimental History states that "there was much marching and countermarching in exceedingly hot weather".

Late in the evening the Battalion received orders to dig themselves in, covering the village of Harveng. But the confusion continued. The Battalion War Diary says: "The men who had by this time been 18 hours under arms under a hot sun, could hardly be kept awake. The marking out of the trenches on unknown ground was difficult. However we did the best we could and the men dug until 11.30pm when we received orders to evacuate the trenches and retire three miles to form a divisional reserve.

Before this could be carried out the order was countermanded". Eventually at 4am they were ordered again to retire, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions forming the rearguard of the Brigade. The Battalion's part in the retreat from Mons had begun - the French were falling back across the whole front, and the BEF had to withdraw with them. Marshal Joffre's strategy was to retreat so as to consolidate a new offensive position on the line of the Somme, near Amiens, 75 miles to the southwest.

The retreat from Mons

The retreat took the 3rd Battalion back along the road up which it had marched only a few days before. The War Diary says: "we passed through many villages through which we had passed on our way from Wassigny to Grougis. It was sad to see all the people packing up all they could carry and flying before the advancing Germans; these same people who had received us with such joy and hospitality only a short time before". The weather continued extremely hot and the pace was gruelling, with many miles marched each day. The Diary continues: "Every day the men were getting more dejected and tired from want of sleep. The heat was intense, the men suffered a good deal from sore feet, and the water question was a constant one".

The retreat involved fighting as well as marching, and the Battalion was involved in two engagements. The first was on 25th August , when the 4th (Guards) Brigade reached Landrecies, after a particularly demanding march. They were looking forward to a well-deserved rest in the barracks there, when they were told by people in the town that Uhlans were approaching with infantry and two guns just behind. The Battalion was turned out and set up outposts round the town. What followed was William Henry's first active engagement with the enemy (and indeed, according to the Regimental History, was the first action in which the 3rd Battalion Coldstream had been engaged since their formation in 1897).

The War Diary says: "At about 7pm a Uhlan patrol appeared at the junction of two roads. They were immediately fired on by our machine gunners, who were with the outpost company, and retired, leaving two of their number on the ground. Captain Heywood then moved up to the road junction and placed our gun so as to sweep each road, and blocked each road with wire. No 2 Coy was now relieved by No 3 Coy, under Capt Hon C H S Monck. Soon after this, information was brought that some French troops were expected. At about 7.30pm the sound of advancing infantry was heard. The men came along singing French songs. Capt Monck challenged, and the answer came back that they were our friends. The officer in front flashed a light on Capt Monck's face, and someone flashed one on to the advancing infantry. The light revealed that in front were men dressed as Frenchmen, and that behind they were all Germans.

"Capt Monck immediately gave the order to fire. Private Robson who was working our machine gun was bayonetted, the men were pushed back, and our gun captured ... German Officers and men rushed in with bayonet and revolver, but were gradually driven back by our fire, and retired to ... the end of the village ... Throughout the night the Germans attacked again and again, but each time they were repulsed by the steady firing of our men ... Shells of high explosive burst all around, covering the faces of all who were there with yellow dye ... About 1am Colonel Fielding brought up one Howitzer gun, and putting it in the firing line, indicated the position where we had seen the flash of the gun which had been firing at us at point blank range. Our howitzer fired about three shots, and evidently hit the German gun, for it did not trouble us again".

By 3.30 am the attacks had ceased and the Brigade was able to evacuate Landrecies and continue the march. But the losses were heavy: 12 men killed, 105 wounded, and 5 missing.

The second engagement took place on 1st September. The 4th (Guards) Brigade was ordered to cover the retirement of the 2nd Division moving southwards through Villars Cotterets. North, east and south of Villars Cotterets is the Retz Forest, which is divided by a network of rides and roads. To cover the retreat of the rest of 2nd Division, 4th (Guards Brigade) took up a position in the Forest. 1st Battalion Irish Guards and 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards were in a position on the northern edge of the forest, the Irish Guards to the west and the 2nd Coldstream to the east. 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards and 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards were in the forest, near the intersection of the north-south road through the forest and the main east-west ride, called Rond de la Reine. In fact the German advance was from the north-west, and hit the Irish Guards and the western end of the 3rd Coldstream positions, at about the same time.

The War Diary says: "The front was a long one, and although the whole Battalion was extended, there were large gaps between companies . We were told that we should have to hold on some time as the division was halting two hours in Villars Cotterets. The CO then went down a portion of our line and was horrified at the long space between nos 2 and 4 coys [on the right of the Battalion's overall position]. The wood was very thick and at various places there were rides leading northwards".

The Brigadier authorised the Grenadier Guards to close up the position, but, according to the War Diary:

"No sooner had the order been given than firing began at close range. The enemy were in large numbers, and all that we could do was to fire at them whenever they were seen, and thus try to check their advance, but it was inevitable that sooner or later the Germans would hit off one of the gaps and pierce our line ....It was not long before the enemy found a gap and the first warning was when we were fired at down the ride. A retirement across the road was ordered, and from this moment it became a retirement of various bodies of men fighting as they retired and doing all that they could to delay the enemy. Eventually the enemy gave up the pursuit and Colonel Fielding collected men of all regiments and fell back on Villers Cotterets. There was no organisation in the fight but a series of fights carried on all along the line by small bodies of men".

According to Drummer Eddie Slaytor, a member of the 3rd Battalion: "All you could hear was this heavy rifly fire, the blowing of bugles, beating of drums and the German's shouting "Hoch der Kaiser". Of course we couldn't see them, we couldn't get at them, so our own fellows were calling out to them "Come out in the open and fight clean" ... They must have got round us because we could see them running across the ride on either side of us not many yards away, and there were bullets flying about in all directions, ricocheting off the treams - smack, smack, smack, smack. It was terrible confusion".

As this indicates, the fighting was heavy and confused. Regiments became intermingled as the Irish Guards fell back on the main brigade line. Support was brought up from other elements of the 2nd Division to assist the withdrawal; and by the time the three Guards Battalions had extricated themselves the German attack had itself fallen into confusion, with German units firing on each other in the thick woods. The Battalion War Diary leaves the casualty figures blank but the Regimental History states that for 3rd Battalion, they were 8 killed, 29 wounded and 8 missing.

The Battle of the Marne

The retreat continued until 5th September. Sir John French had been severely shaken by the extent of losses and casualties in the campaign so far, and was concerned that the BEF would collapse without given a respite for rest and to re-equip. It took a visit to Paris from Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, to tell him that his task was to co-operate with Marshal Joffre, even at extreme risk to his own army. On 5th September Sir John French met Joffre, who appealed to him "in the name of France" to resume the offensive, and on 6th September, the BEF once more started marching forward.

The 3rd Battalion's turning point was at Fontenay, which they had reached on 5th September. On 6th September "pursuing the enemy" they were at Tonquin, on 7th September at Les Sauter - and so far the going was relatively easy, as in front of this section of the BEF, the Germans were falling back without attempting to delay the advance. However, on 8th September the 4th (Guards) Brigade were due to cross the river called the Petit Morin, a tributary of the Marne. 3rd Battalion Coldstream was in the vanguard.

On approaching a thickly wooded ravine with roads leading down into the river valley, the Battalion came under heavy shell and machine gun fire from Boitron, a village on the further ridge, and could not make the crossing. The 2nd Battalion Coldstream and 2nd Battalion Grenadiers were able, however, to cross the river further up, at La Forge, out of view of the enemy, and they were able to work up the further slope, come round behindthe village, and drive the Germans out of it. This enabled the 3rd Battalion to cross the river and enter Boitron also.

The War Diary continues: "In the wood there was still some [enemy] infantry and a batter of machine guns. These ... opened fire [but the left company of 2nd Coldstream] quickly changed direction to the left [and]] 3rd Coldstream and the Irish Guards quckly extended facing the wood and attacked. The enemy saw the hopelessness of their position. The German Machine Gun Battery, which had suffered severely, and many of the infantry at once surrendered. The retreating enemy continued to lose heavily from our artillery fire as they retired in some disorder, and left the battlefield with their dead and wounded lying on the ground."

That night the Battalion bivouacked where they were, near Petit Villiers, the next village northwards along the road from Boitron. Their casualties were eight killed, 45 wounded, and 6 missing, though that night reinforcements arrived for all three Coldstream Battalions. On 9th, 10th and 11th the pursuit was continued, but without contact with the enemy. The War Diary observes: "The morale of the Battalion had greatly improved by now. Throughout the trying retreat between [gap left blank] the men had been severely tested though at all times taking everything into consideration they had been wonderfully cheerful".

The Battalion did not know it but, even as they were fighting for the village of Boitron, the German high command had decided, in the light of the French and British attack, and in particular because of the risk of the BEF coming between the German 1st and 2nd Armies, to withdraw from their positions threatening Paris to safer and defensive lines above the next river system beyond the Marne, that of the Aisne. The Battle of the Marne was over.

The Regimental History concludes this section of its narrative as follows: "The Battle of the Marne transcends in its colossal magnitude any previous conflict recorded in history. It was a stupendous struggle which spread from the valley of the Moselle in Lorraine round Verdun to that of the Ourcq north of Paris, and it has been computed that forty-nine infantry and eight cavalry divisions of the Allies were pitted on that occasion against forty-six infantry and seven cavalry divisions of the Germans. It followed immediately after the precipitate retreat from the Belgian frontier that began in the latter part of August. That this disaster should in a fortnight's time be suddenly changed into a striking victory was very naturally a complete surprise and a puzzling problem to the world at large, and the causes that brought about this extraordinary event will for long occupy the attention of military students" - and indeed, so it has proved.

Death

During this first period of the war the 3rd Battalion had suffered many casualties: 220 men were killed, wounded or missing; and of the officers, four had been killed, and nine were wounded, of whom one was invalided out permanently. William Henry Howe was one of these casualties. He had participated with his Battalion in the march to the front, the "precipitate retreat" and the "stupendous struggle", but at some point during the Battle of the Marne, he was wounded. The Dartmouth Chronicle of 16th October 1914 carried the following short piece:

Wounded at the Battle of the Marne

Mr F Howe, of Mansard Terrace, Dartmouth, has received information that his brother, Private W H Howe, of the 3rd Coldstream Guards, who was wounded in France, is dangerously ill at Netley Hospital.

The writers of the 3rd Battalion War Diary, though they recorded deaths and wounding of their fellow officers individually, did not do the same for the men. William Henry is not mentioned by name, nor is there any reference to any members of the Battalion being sent to hospital. However, as the only date on which the Battalion was in action after the retreat from Mons and during the Battle of the Marne was during the action to take the village of Boitron, it was presumably there, on 8th September, that he was wounded.

In an early entry in the the "Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front 1914-1915" attributed to Sister K E Luard RRC, QAIMNSR, the writer describes the planned casualty evacuation process:

"The wounded are picked up on the field by the regimental stretcher-bearers ... they take them to the Bearer section of the Field Ambulance ... who take them to the Tent Section of the same Field Ambulance, who have been getting the Dressing Station ready ... They are drilled to get this ready in twenty minutes in tents ... The Field Ambulance then takes them in ambulance waggons ... to the Clearing Hospital, with beds. From the Clearing Hospital they go on to the Stationary Hospital - 200 beds - which is on a railway, and finally in hospital trains to the General Hospital, their last stopping place before they get shipped off to Netley and all the English Hospitals".

To begin with, the base hospitals for the BEF were to be in Le Havre, which was the main supply-base for the BEF, and forward hospitals had been established at Rouen. In early September, however, due to the German advance, the whole supply-base, including the hospitals, was moved to St Nazaire - Sister Luard arrived there on 5th September aboard the RMSP Asturias Hospital Ship. Rouen was also closed. Furthermore, the fluctuating situation on the front line made it very difficult for the medical services to know where to establish forward hospitals. Sister Luard's diary gives a clear indication of what William Henry is most likely to have experienced on his journey from the front.

On 13th September she was ordered to Le Mans, where a Stationary Hospital had been established in the "rather grimy" Bishop's Palace. The situation was still confused and she was still awaiting orders for her final destination. Already the casualty evacuation chain was slow and under strain. On Friday 18th September, the medical services were still dealing with casualties from the Battle of the Marne, a week earlier. On that day, she wrote: "They have been busy at the station today doing dressings on the train. A lot have come down from this fighting on the Marne". The following day she wrote: "They are all a long time between the field and the hospital. One told me he was wounded on Tuesday - was one day in a hospital, and then travelling till today, Saturday. No wonder their wounds are full of straw and grass ... Most haven't had their clothes off, or washed, for three weeks, except face and hands".

On Sunday 20th September, three train-loads of casualties arrived, from the fighting at the Aisne. She wrote "You boarded a cattle truck, armed with a tray of dressings and a pail; the men were lying on straw; had been in trains for several days; most had only been dressed once, and many were gangrenous. If you found one urgently needed amputation or operation, you called an MO to have him taken off the train for Hospital". She then went in a train with the wounded to St Nazaire. On the Monday, she wrote: "The Medical Officers at St. N told us there were already two trains in and no beds left on hospitals or ships, and 1300 more expected to day".

From St Nazaire, William Henry would have been taken by hospital ship to Southampton. The Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, which had been completed in 1863, was the largest military hospital every built. By 1900 it had its own railway station, constructed in 1900, connected to the main line from Southampton, and hospital trains brought casualties directly to the hospital from the port. However, as Netley's medical records for British soldiers were destroyed when the hospital was closed and demolished in 1966, the date of his admission to the hospital is not known.

As there is nothing about William Henry in the Dartmouth Chronicle edition of 9th October, Frank Howe, his elder brother, presumably received news of him sometime a few days after that date. But even as this news appeared in the newspaper, William Henry had died. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, and SDGW, have his date of death as 15th October 1914. The announcement in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 23rd October, presumably placed by Frank, gave his date of death as the following day:

Deaths: October 16th at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, William Henry Howe, age 25 years

Our database uses the earlier date pending any further clarification which may become available from any other source.

William Henry is buried in the Netley Military Hospital, in the non-conformist section, in what is now the Royal Victoria Country Park, where his grave is marked by a Commonwealth War Grave Commision gravestone. A photograph of the grave may be found on the following website about the cemetery:

http://www.netley-military-cemetery.co.uk/commonwealth-war-graves-wwi-wwii-u-k/holm-ives/

Medals

William Henry's Medal Roll Index Card shows he was awarded the 1914 Star, with a Clasp. The 1914 Star was awarded to all those who served with the establishment of their unit in France and Belgium between August 5th 1914 and midnight November 22nd/23rd 1914. A bar clasp was given to all those who qualified for the 1914 Star and who served under fire. It was necessary to apply for the issue of the clasp (but not necessary to apply for the 1914 Star) so this must have been done by William Henry's family, after his death. Personnel entitled to a 1914 Star automatically met the conditions for the award fo the British War Medal and the Victory Medal.

Commemoration

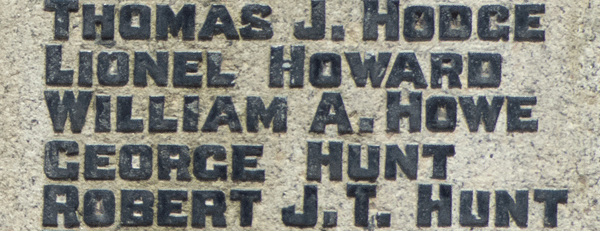

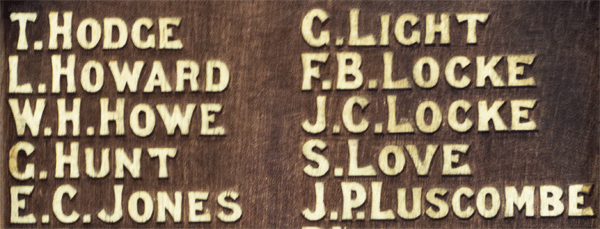

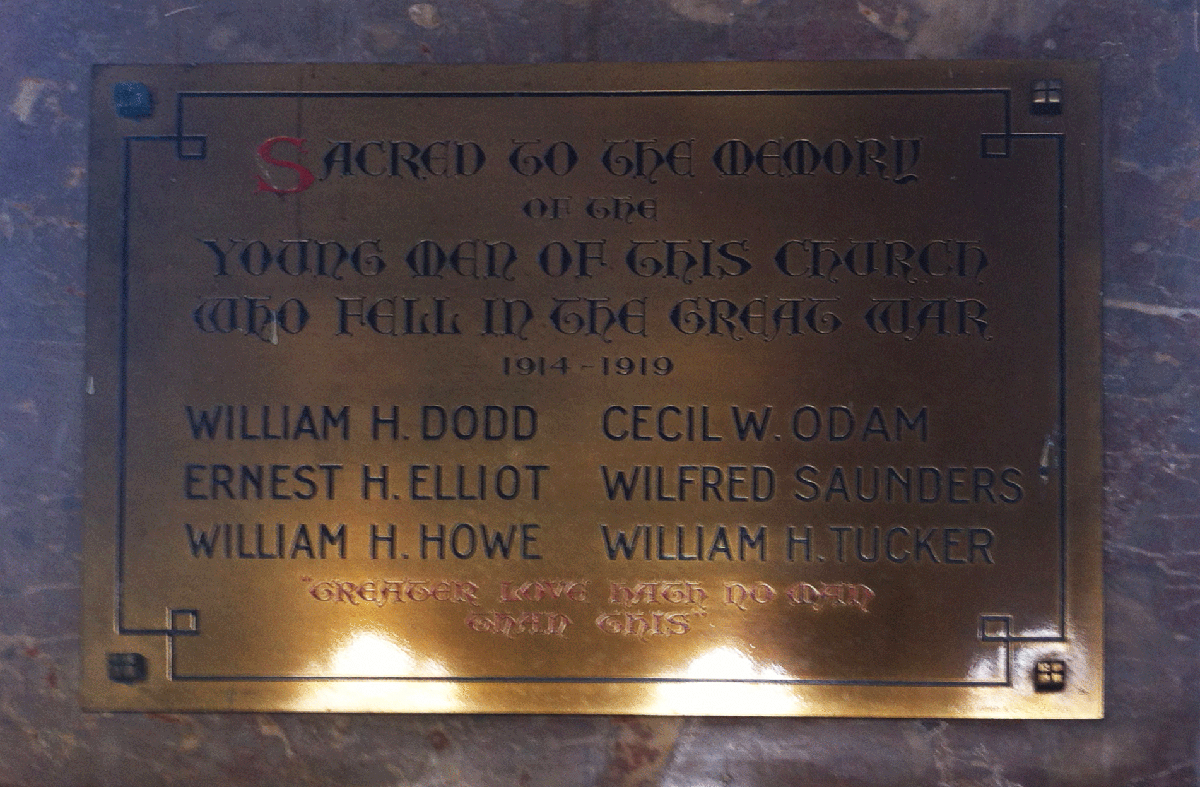

William Henry is commemorated in Dartmouth on the Town War Memorial, on the St Saviour's Memorial Board and on the Memorial Plaque in the Flavel Church.

On his gravestone at Netley, it is shown as H. Howe.

Sources

National Archives:

George Howe, born Devon, attestation papers to serve in the Royal Marines 1864 ADM 157/324/121

Royal Navy Service Record for William Henry Howe ADM 188/555/364121

The website Army Service Numbers 1881-1918 enables William Henry Howe's date of joining the Coldstream Guards to be identified by his regimental number. According to his Medal Roll Index Card, Soldiers Died in the Great War (SDGW), and his appearance on the provisional roll of honour for the War Memorial published in the Dartmouth Chronicle in 1919, his army service number was 8300; however, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records have a slightly different number, 8306. Whatever the last digit of his regimental number, the first two, "83", mean that he joined sometime between 8251, who joined on 9th January 1910, and 8577, who joined on 10th January 1910. The website page on the Coldstream Guards is here.

Histories of the Coldstream Guards accessed from the regiment's official website ("history" section):

- The Coldstream Guards 1885-1914, by Sir John Hall

- The Coldstream Guards 1914-1918, by Lt Col Sir John Foster George Ross of Bladensburg (2 volumes and maps)

- War Diary of 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards accessed online at National Archives, reference WO 95/1342/3 (there is a fee to download).

For a more detailed account of the Battle of Villers Cotterets and the Battle of the Marne, see the relevant pages on www.britishbattles.com.

The quotation from Drummer Eddie Slaytor of the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards is included in 1914, The Days of Hope, by Lyn Macdonald, publ. Penguin Books, 1989.

The Diary of a Nursing Sister on the Western Front 1914-1915 is available to download free from Project Gutenberg.

See also the information on the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service in the First World War on the Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps website.

General background: John Keegan, The First World War, publ 1998, Hutchinson.

Websites quited above accessed 28th September 2014.

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Howe |

| Forenames: | William Henry |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 8300 or 8306 |

| Military Unit: | 3rd Bn Coldstream Guards |

| Date of Death: | 15 Oct 1914 |

| Age at Death: | 25 |

| Cause of Death: | Died of wounds |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of the Marne |

| Place of Death: | Royal Victoria Military Hospital |

| Place of Burial: | Netley Military Cemetery, Hampshire |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | Yes |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |