Robert Prowse Hearn

Robert Prowse Hearn was born in Dartmouth on 4th August 1885 and baptized in St Saviours on 4th October 1885. He was the fifth son and eighth child of John Emanuel Hearn and his wife Elizabeth Prowse.

John Emanuel Hearn was the son of a mariner but instead of going to sea, he was apprenticed to a shoemaker and in time, became a Master Cordwainer, making and selling boots and shoes. He married Elizabeth Prowse, from Sherford, in St Clements on 23rd February 1869.

John and Elizabeth had a large family, three daughters and seven sons:

- Edith Emily, born 1870

- Elizabeth Kate, born 1873

- John William, born 1875

- William Charles, born 1877, died 1878 aged 11 months and buried at St Clements

- Samuel Partridge, born 1879

- Joseph Partridge, born 1881

- Lizzie Alberta, born 1882

- Robert Prowse, born 1885

- Stanley George, born 1888

- Leonard Webb, born 1890. Leonard is also on our database.

In addition to the loss of their son William when only eleven months old, John and Elizabeth also suffered the loss of their adult son John, a carpenter. He died in 1908 in Dartmouth, of acute pneumonia, aged 32. He was buried at St Clements alongside his infant brother.

The 1911 Census recorded John, Elizabeth, and four of their adult children living at 5 Victoria Terrace, Dartmouth (also living with them was Elizabeth's widowed sister, Harriett). None of the children followed their father into the shoe business. Elizabeth Kate, unmarried at 38, worked as a dressmaker; Stanley, age 23, worked as a science laboratory assistant, at the Royal Naval College; and Leonard, age 20, was a law clerk in a solicitors office. Robert, aged 25, was a "bank clerk" in a "banking company".

Two of Robert's married siblings were still close by. Lizzie, who had worked in the postal service as a telephone operator, had married in 1902. Her husband, Granville Wellington, was a baker. By 1911 they ran a shop and bakery in Blackawton. Joseph was a house painter; he had married in 1908 and he and his wife Janie lived in Dartmouth. Samuel, however, had left Dartmouth. He and his wife Rose lived in Fulham, London, with their three children. Also living with them were Samuel's cousins Charles and William, sons of Samuel Partridge Hearn senior, a shipmaster who had been lost at sea in 1903.

Sometime after 1911, Robert also moved to London - the Dartmouth Chronicle reported at the time of his death that "he was formerly employed in an office in London" and that he had previously worked for Elder Dempster Shipping Ltd, a steamship company which had its origins in the trade between the UK and West Africa.

Service

Robert's service papers have not survived, but from his service number it would appear that he joined the Royal Fusiliers in late September/early October 1914, one of the many volunteers responding to Lord Kitchener's appeals. He joined the 22nd (Kensington) Battalion, so called because it was raised by the Mayor of Kensington, Alderman William H Davison, from volunteers in the borough. "Soldiers Died in the Great War" records that he enlisted in Shepherds Bush. Also forming part of this battalion were colonial volunteers; the regimental history observed that "the battalion combined a very good type of Londoner and a very good type of colonial, and the two amalgamated very successfully". This may be why Robert was recorded in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 2nd November 1914 as having joined the "Imperial Fusiliers".

The battalion trained first at White City, then at Roffey, near Horsham; Clipstone Camp, and finally Tidworth. They left Tidworth for France on 16th November 1915, as part of 99th Brigade. After a short period of familiarization with trench warfare at Annequin, between Béthune and La Bassée, they went into the trenches for the first time on their own on 14th December 1915. At this time, things were very quiet, though they suffered occasional casualties. They were in the trenches for Christmas Day 1915 - the battalion's War Diary sternly records that "any attempt on the part of the enemy to fraternise during Xmas or the New Year is to be met immediately by hostile action on our part".

They remained in and around this part of the front for the next six months. Short spells of duty in the trenches, usually of four or five days, were interspersed with much longer rest periods. Casualties were fairly light until an unfortunate episode on 22nd May, while in the trenches at Souchez - the War Diary records:

Orders for an attack at 8.25pm in conjunction with Battalions on right and left were issued. At 8.15 pm as the 1st R Berks were unable to prepare to advance owing to the heavy barrage, the Commanding Officer (Major Rostron) cancelled the advance [but] the message did not reach B Company which advanced and took the German trench, remaining in it for an hour and a half until recalled.

Casualties from this mishap (or worse) were three officers wounded (one of whom later died), 7 OR killed and 78 wounded, two of whom subsequently died.

They were still in this sector of the front on 1st July 1916 and were not summoned south to the Somme until 16th July; they finally arrived on the front line at the Somme on 24th July, at Montauban (see the stories of Robert Willing, Robert Hunt and Jack Butteris for the initial attack there).

This fortified village, which had formed part of the German second line system, was now held by the British, and was the starting point for the next part of the move forward. The 22nd Battalion were to be part of the continuing fight for Delville Wood, a short distance to the north of Montauban.

Peter Hart describes the overall situation there as follows:

Perhaps the most futile series of attacks [on the Somme after 1st July] were launched against a small wood with a burgeoning reputation as a hell hole and the name to match - Delville Wood ... [From] 15th July to 3rd September ... the British struggled to capture and then hold the blighted wood and the ruins of the adjoining village, Longueval. In peacetime the 156 acre wood had a typically sylvan aspect, with mingled oak and birch trees interspersed with thickets of hazel and undergrowth, the whole divided by a series of "rides" or breaks in the trees. But by mid-July the trees were smashed down, ripped into tangled heaps by the shells and the "Devil's Wood", as the troops unsurprisingly called it, presented a fearsome prospect.

The South African Brigade had entered the wood on 15th July. They had managed to capture all but the north-western portion, but were then subject to intense attack. They held their positions as long as they could, but were forced eventually to fall back on Prince's Street, the main ride cutting across the wood from east to west. After huge losses, they were relieved on 19th/20th July. The 53rd Brigade then had to hold on to the captured portion of the wood against tremendous bombardment, sniper fire and many attacks from small parties of enemy troops, until they were relieved themselves on 22nd July. Many other Brigades were also involved in successive attacks on Longueval and the wood.

On 27th July, it was the turn of 99th Brigade. The 1st Kings Royal Rifle Corps and the 23rd Bn Royal Fusiliers were in front, the 1st Royal Berkshires in support. A and B Companies of the 22nd Royal Fusiliers were detailed as carrying parties; C & D Companies were in Brigade Reserve. However, all found themselves thrown into the fight. The Regimental History of the Royal Fusiliers describes the circumstances:

Four battalions of the Royal Fusiliers had their share in this memorable exploit ... Words fail to do justice to the situation at this moment. It was hot weather. The ground was pitted and torn by shell fire. Dead bodies lay about, and before the troops began to move up the Germans had indulged in a heavy bombardment with gas shells ... The wood was now merely a collection of bare stumps, but the trees which had crashed and the thick undergrowth provided ideal obstacles and cover. The ground seemed to be alive with machine guns, and the German barrage effectually cut off all approach to the wood.

A very heavy British artillery bombardment had preceded the advance, with pronounced effect. The 23rd Royal Fusiliers went in first, reached Princes Street quickly, and were able then to progress to secure the far edge of the wood. But they were then subjected to intense enemy shelling which caused many casualties. 1st KRRC, who were holding the exposed flank on the right of the wood, required reinforcement during the day. The Regimental History continues:

At 1pm a message was sent to the 22nd to reinforce the KRRC... . Before the end of the day every available man of the 22nd was thrown into the struggle on the right. At 3.30pm a strong counter-attack was delivered by the enemy on this flank, and the situation was only cleared up by the assistance of the 23rd's bombers and the full remaining strength of the 22nd. Captain Walsh collected all the carrying parties, to the number of about 250, and organized them into a fighting unit. Captain Gell took the last 100 men of C and D Companies up to the wood from Bernafay Wood, and with them held the south-east flank of the wood. The wood undoubtedly justified its nickname on this day. Wherever the men stood they were under shell fire, and it seemed impossible that any troops should be left to hold what had been won. But at the end of the day the wood was handed over intact ... Largely owing to [the 22nd] the flank was held up, and unless this had been accomplished the wood would have been lost almost before it was won.

(The 17th Middlesex and men from other units were also collected up and sent in as part of the reinforcements).

On 28th July the wood was temporarily cleared; but fighting continued there for some time to come.

Death

The 22nd Battalion's War Diary on 27th July records that casualties were: "Captain C Grant, commanding Brigade Machine Company, killed; four officers wounded; other ranks, 26 killed, 143 wounded and 20 unaccounted for". On 29th July, "men continued to come in, especially men of the Lewis Gun team and of the 64 men who were carrying party to the Machine Gun Company on the 27th". There was clearly some uncertainty after the attack about total numbers killed and wounded. But no casualties were reported on 26th July, the day before the attack.

However, John and Elizabeth Hearn received a letter from 2nd Lt Holmes of the 22nd Battalion, which recorded Robert's death on 26th July. The Dartmouth Chronicle of 11th August 1916 carried the following story:

Buried Where He Fell

Dartmouth Man's Supreme Sacrifice

We regret to hear that Private Robert P Hearn, 22nd Royal Fusiliers, son of Mr John Hearn, Victoria Road, one of the Mayor's macebearers, has been killed at the Front. The sad intelligence was conveyed to Mr and Mrs Hearn in a letter from Second Lieutenant A K Holmes, who wrote: "I cannot tell you how sorry I am to write you of the death of your son, R P Hearn, who was killed in action on the 26th July last. I hope you will be able to comfort yourselves in the thought of his noble death, fighting for his country. Your son was helping in the working of a machine gun when he was shot down, and we believe he died without any pain, and was buried where he fell. He was much beloved by all who knew him, and was an example to all, in the fearless way he carried out his duties in the midst of a most terrible fire from the enemy. I cannot write more now except to again express the deep sympathy of us all for you".

Accordingly John and Elizabeth placed an announcement of Robert's death in the same edition of the Chronicle:

Hearn- Killed in action on July 26th, Robert Prowse, fifth son of Mr and Mrs J E Hearn, 5 Victoria Terrace, age 30

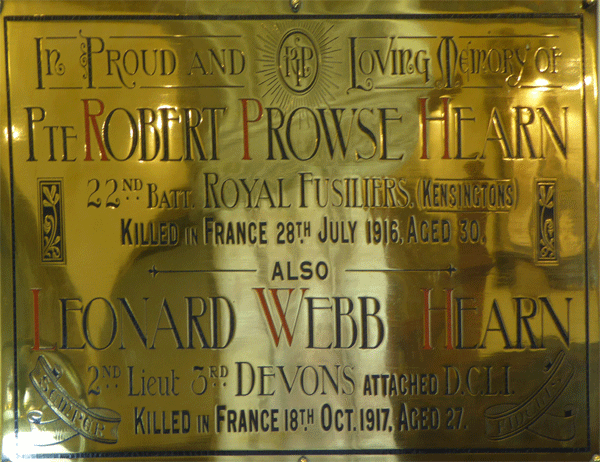

However, later Army records give Robert's date of death as 28th July, as do Commonwealth War Graves Commission records; and the memorial tablet erected in St Saviour's by the family to Robert also shows his date of death as 28th July 1916.

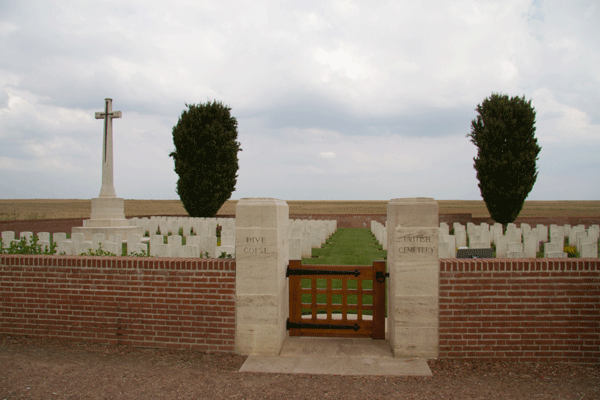

Furthermore, notwithstanding the statement in 2nd Lt Holmes' letter that "he was buried where he fell", Robert was buried at Dive Copse Cemetery, at Sailly le Sec. Sailly is several miles south west of Delville Wood, on the banks of the Somme. The CWGC states that the ground north of the cemetery "was chosen in June 1916 for a concentration of field ambulances, which became the XIV Corps Main Dressing Station. Plots I and II were filled with burials from the medical units between July and September 1916." Robert lies in Plot II.

So it would appear that Robert was not killed outright but was most likely seriously wounded in the attack on Delville Wood on 27th July; and that he was taken to the Main Dressing Station at Sailly, and died either on his way there or soon after having reached there, the following day. We have therefore recorded his date of death as 28th July 1916.

If he was "helping in the working of a machine gun when he was shot down", he may have been one of the "men who were Carrying Party to the [Brigade] Machine Gun Company", who "were continuing to come in" on 29th July, and about whom there was evidently some uncertainty. But none of the available records gives Robert's Company and he is not mentioned by name in the Battalion War Diary.

Robert was buried at Dive Copse Cemetery, at Sailly le Sec, several miles south west of Delville Wood.

Commemoration

In 1918, before the end of the war, John and Elizabeth commissioned a brass memorial tablet for Robert and his brother Leonard, for the north wall of St Saviours.

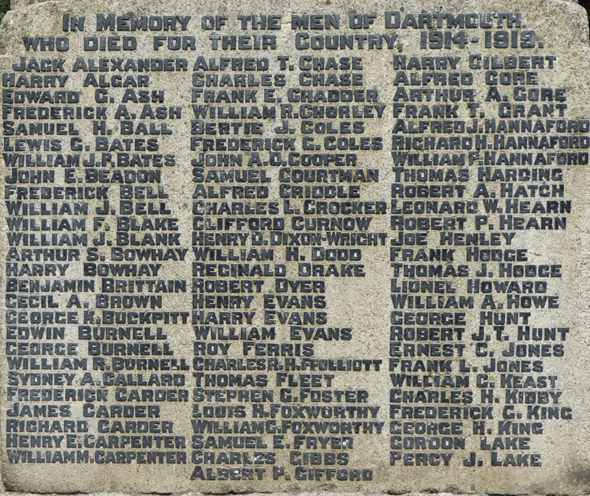

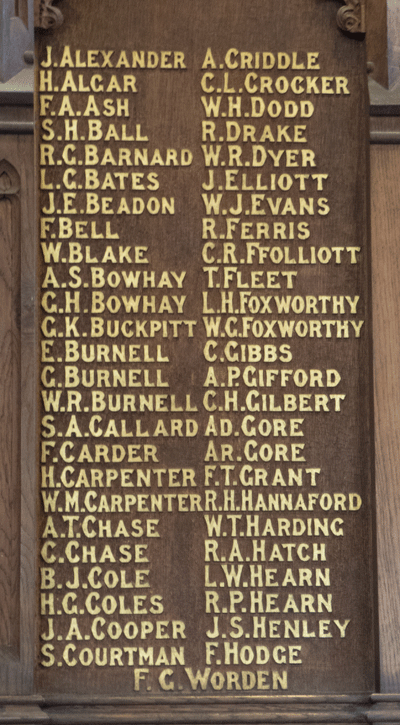

Robert is also commemorated on the Dartmouth Town Memorial and the St Saviours Memorial Board.

Robert's brothers

The Dartmouth Chronicle recorded at the time of Robert's death that:

Mr and Mrs Hearn have four sons now serving in the Army. One of them, Captain Stanley Hearn, of the 6th West Yorkshires, left Dartmouth for the front on Tuesday, whilst another, Private J P Hearn, of the Royal Defence Corps, is home on sick leave.

Robert's eldest brother, Samuel, had volunteered on the day war was declared to serve with the British Red Cross Society. He served in Egypt from 27th June 1915 to 13th October 1915. In 1917, he joined the Royal Engineers but served at home.

His next eldest brother Joseph enlisted with the Royal Defence Corps on 17th December 1914 but was discharged "sick" on 18th October 1916. The Royal Defence Corps provided forces for home defence tasks such as guarding military bases and prisoner of war camps.

Robert's younger brother Stanley, who at the outbreak of war was the Colour Sergeant of "F" company (Dartmouth) 7th Battalion Devon Regiment (Cyclists), was gazette Second Lieutenant in the 6th Battalion Prince of Wales Own (West Yorkshire Regiment) on 5th May 1915. Stanley was apparently at home in early August, but also fought on the Somme, being was wounded in his Battalion's attack near St-Pierre-Divion, north-west of Thiepval, on 3rd September 1916. He survived the war.

Leonard's story will be published on the centenary of his death in 2017.

Sources

War Diary of the 22nd Battalion Royal Fusiliers available for download at The National Archives, fee payable, reference WO 95/1372/2

The Royal Fusiliers in the Great War, by H C O'Neill, OBE, publ Heinemann, 1922

Army Service Numbers, Royal Fusiliers

The Somme, by Peter Hart, publ Cassell 2006

Somme 1916, A Battlefield Companion, by Gerald Gliddon, publ History Press, 2016

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Hearn |

| Forenames: | Robert Prowse |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 522 |

| Military Unit: | 22nd Bn (Kensington) Royal Fusiliers |

| Date of Death: | 28 Jul 1916 |

| Age at Death: | 30 |

| Cause of Death: | Died of wounds |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Battle of Delville Wood (Somme) |

| Place of Death: | Sailly-le-Sec, France |

| Place of Burial: | Buried Dive Copse British Cemetery, Sailly le Sec, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Private Memorial: | To the Hearn brothers in St Saviour's, Dartmouth |

| On Another Memorial? | No |