Noel Jardine Exell

Noel Jardine Exell was born in Stoke Fleming, near Dartmouth, and was a grandson of George Parker Bidder, who had become nationally famous in his youth, and in later life lived in Dartmouth. Although Noel was not commemorated on public memorials in Dartmouth, he is on our database because his death was announced in the Dartmouth Chronicle and the newspaper carried a full obituary.

Family

Noel Jardine Exell was born on 6th December 1890 in the Rectory at Stoke Fleming, where his father was Rector. He was the second child and only son of Joseph Samuel Exell and his wife Florence Bidder. Noel was baptised by his father at St Peter's Stoke Fleming on 15th February 1891.

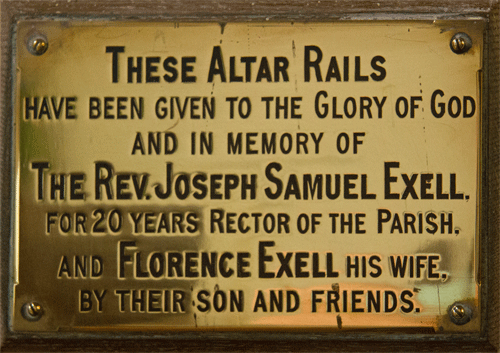

His father, Joseph Samuel Exell, was the son of a Wesleyan Minister, Joseph Exell, but made his career in the Anglican church, being made deacon in 1881 and ordained priest in 1882. From 1881-1884 he was curate at Weston-super-Mare and from 1884-1890, Vicar of Townstall with St Saviour, Dartmouth. He became Rector of Stoke Fleming in 1890, and remained there until his death. He was also a prolific author of religious works and (according to his obituary in the proceedings of the Devonshire Association) "a preacher of much eloquence and possessed of great talent".

His first wife, Elizabeth Anne Sabine (née Blake) by whom he had a daughter, Sharlie Elizabeth, in 1876, died prematurely aged 44, and was buried at St Clements Townstal, Dartmouth on February 24th 1885. Just over a year later, on 6th March 1886, Joseph married again, at St Peter's Stoke Fleming. His second wife, Florence Bidder, was the youngest daughter of George Parker Bidder.

George Parker Bidder, born in Moretonhampstead, had been famous in his youth as "the Calculating Boy". His father, William Bidder, a stonemason, had taken George around the country, when a boy, to exhibit him and his prodigious powers of calculation, and his fame had spread far. For example, on Monday 3rd April 1815, the Morning Post reported from Windsor that:

On Thursday, Master George Bidder, the wonderful calculating boy, who is only eight years of age, was introduced to the Queen and Princesses by the Bishop of Salisbury, when he gave specimens and proofs of his surprising powers .... [including] ... what number multiplied by itself will produce 36,372, 951. Answer, 6031; he answered this in eighty seconds. The next question was, How many minutes in forty years, answer 25,754,400; answered in two seconds ....

On Saturday 7th October 1815, the Carlisle Journal reported him at Margate:

... astonishing the salt-water drinkers. One of the Stock Exchange brokers asked the following question: Suppose the moon to be distant from the earth 123,256 miles, and sound to travel at the rate of 4 miles in a minute, how long would it be before the inhabitants of the moon could hear of the Battle of Waterloo? Answered by the boy in two minutes - 21 days 9 hours and 34 minutes!

In 1819 his travels took him to Edinburgh, and he attracted the attention of a group of benefactors, led by Sir Henry Jardine, who provided him first with a year with a private tutor and then with a university education at Edinburgh. Sir Henry Jardine remained his mentor in his professional career, finding him a post in the Ordnance Survey. From there he moved into civil engineering, and developed a close professional association with Robert Stephenson, the son of the railway engineer George Stephenson. Together they worked on railways in the UK and abroad. George Parker Bidder was also closely involved with the development of the London Docks and with many other major engineering ventures.

Robert Stephenson and George Parker Bidder were both yachting enthusiasts and in 1858 they attended Dartmouth's Regatta. Shortly after, George Parker Bidder bought a house in Dartmouth, on Paradise Point, Warfleet, which he renamed Ravensbury. He was elected a town councillor, was a founder member of the Dartmouth Yacht Club, and was closely involved in various schemes to improve the town. In close association with Samuel Lake, another leading Dartmouth businessman, he commissioned the first steam powered fishing trawlers.

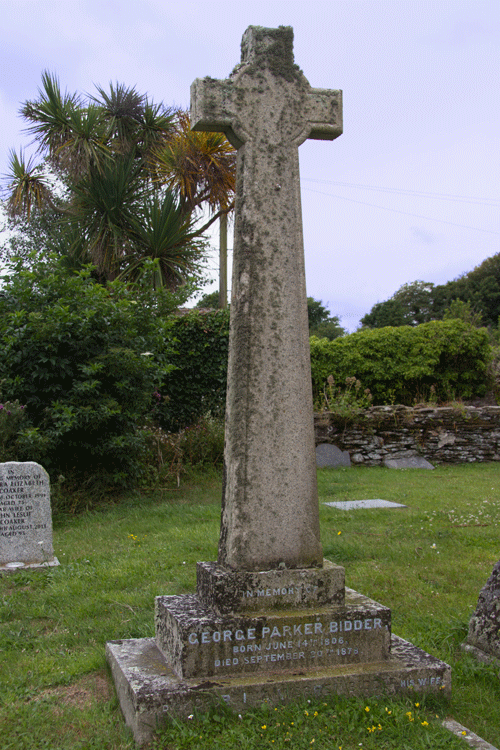

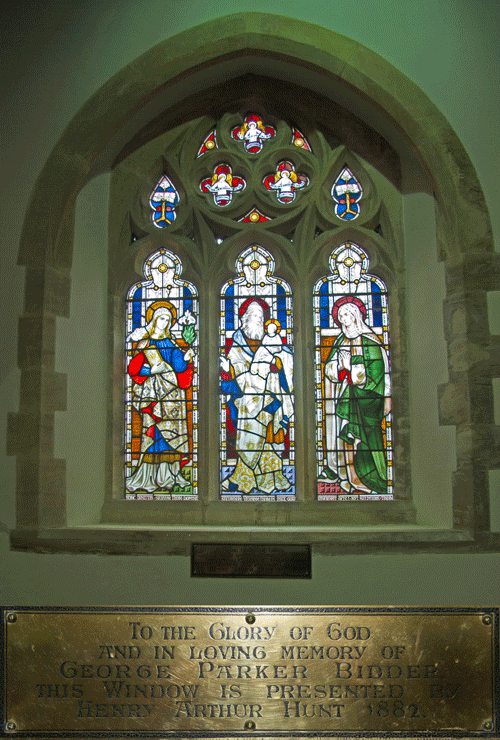

In 1877 George Parker Bidder bought Stoke House in Stoke Fleming but sadly died the following year at Ravensbury, Dartmouth, before he was able to move to his new house. It became the home of his widow, Georgina, who remained at Stoke House until she died, in 1884, and of his unmarried daughters, the last of whom died there in 1937. Both George and Georgina (and other members of the Bidder family) were buried in the churchyard of Stoke Fleming. George is also commemorated by a stained glass window inside the church.

Noel Jardine Excell was therefore surrounded, as he grew up in Stoke Fleming, by members of the Bidder family, both alive and dead. He was educated first at a preparatory school in Bournemouth (where he was recorded in the 1901 Census) and then at Charterhouse, where he was a member of Bodeites House. He left Charterhouse in 1907.

His mother died in 1908 at the comparitively early age of 54 and was buried in Stoke Fleming churchyard, and his father died suddenly only two years later, at the age of 61, and was buried beside her. His stepsister, Sharlie, had married in 1901, Albert Dallas Enriquez, a widower, and a Lt Colonel in the Indian Army, and lived abroad.

Evidently Noel decided to join the Army. In 1909 he was commissioned into the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion, Cheshire Regiment, from which, in 1912, he passed the examination to join the Army as a Second Lieutenant, joining 18th (Queen Mary's Own) Hussars on 22nd May 1912. He competed in the Navy and Army Boxing Championships in November of that year, sustaining a dislocated jaw when he was knocked out in the early rounds of the officers' middle-weight competition.

Also towards the end of 1912 he married Ellen Ruby Warwick. She was born in Veryan, Cornwall, the younger daughter of Samuel Warwick, an agricultural foodstuffs merchant, and his wife Sarah, from Truro. Noel's marriage seems to have prompted him to take a new direction as shortly afterwards, on 15th February 1913, he resigned his commission. Three months later, on 12th May 1913, he embarked at Southampton upon the steamship "Kleist", travelling to Algiers - and, according to his obituary in the Dartmouth Chronicle, he was still there at the outbreak of war.

Service

When war was declared, Noel returned to England to rejoin the Army, and was gazetted temporary lieutenant on 11th September 1914. During his first few months, he was engaged in raising and training Kitchener's New Armies. He served first in 10th Battalion The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), the so-called "Stockbrokers Battalion" - recruited over a few days in August 1914, and by the time he joined them in September, already in training in Colchester.

In January 1915 he was appointed temporary captain in 15th (Reserve) Battalion Kings Royal Rifle Corps, and, according to the obituary in the Dartmouth Chronicle, in March "made an appeal through the medium of our columns to local lads to enlist in his Company". However, on 15th April 1915 he was transferred to the 9th Battalion, with which he went to France when the Battalion was mobilised in May, in command of "A" Company. The 9th Battalion was under command of Lt Colonel Charles Slingsby Chaplin, who had commanded the 3rd Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps until 1912 and came out of retirement to form and lead the 9th (Service) Battalion. They were destined for Ypres.

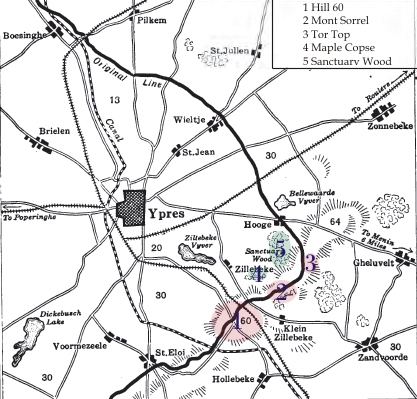

By 31st May the Battalion was billeted at Canada Huts, Dickebusch, four miles southwest of Ypres. Their first job was to march three miles to a point on the Yser canal one and a half miles due south of Ypres to dig 600 yards of reserve trenches overnight. This they did for several nights, while behind them, Ypres was a mass of flames from German shelling.

On 5th June, the Battalion was attached to 13th Infantry Brigade, 5th Division, for their training in trench warfare. Over the next few days at St Eloi, they suffered their first casualties.

By 11th June, they were back in Canada Huts. The Battalion War Diary noted: "Very heavy gun fire during night and early morning. Vlamertinghe church spire disappeared during night". Noel Exell, together with Captain Andrew Tanqueray of "B" Company, was sent out on a reconnaissance mission through Ypres in the afternoon - there were rumours of a move.

On 14th June they were in huts outside Vlamertinghe, west of Ypres (which continued to be heavily shelled) so they spent their time digging shelters, for protection. On the evening of 15th June they marched to the Lille Gate at Ypres. A British attack was underway at Bellewaarde and the 42nd Infantry Brigade, of which the Battalion was a part, was ordered to move up in support. Their route was along the Ypres-Roulers railway line but progress was slow and they were under fire for much of the time. They got as far as the assembly trenches but were then sent back to Vlamertinghe. Lt Bourke, of A Company, was killed by very heavy shrapnel fire as they came up into the assembly trenches; five other ranks were also killed. The War Diary reported that one officer and 58 other ranks were wounded, one of whom subsequently died. The following day the Battalion was complimented by the CO on their behaviour "under trying and novel conditions".

After "a quiet day in huts" the Battalion on the evening of 19th June once again moved out of Vlamertinghe towards and through Ypres, to take up a position on the front line either side of the Ypres-Roulers railway, east of Ypres, until 25th June, when they went into billets at Poperinghe. On 8th July they were moved forward again, to the "GHQ" line (the line of defence closest to the city). Here they were subjected to shelling and bombardment with gas but fortunately casualties were slight. They moved forward into the front line on 12th July. The trenches had been damaged by "whizzbangs" (a light shell fired from a smaller calibre field gun) so they set about repairing them. More whizzbangs caused several casualties on 16th July; they also had to contend with the effects of very heavy rain on several occasions. The Battalion Diary noted that "from 13th-18th every man in trenches worked strenuously improving and repairing trenches and sapping".

On 19th July they were relieved and marched to "rather uncomfortable" bivouacs in "Basseboom" (Busseboom near Poperinghe), where they were in reserve at one hour's notice and provided "working parties" for various tasks - for example, on 23rd July a working party of 200 men went to Ypres by bus to work on gun emplacements. Although they were well behind the lines they were freqently subject to heavy shelling (the Poperinghe area was well within range of the heavier German guns) and there were several casualties.

Death

On 21st July, while the 9th Battalion was at Busseboom, 175 Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers exploded a large mine under two new redoubts built in the German lines at Hooge. In a huge explosion, one redoubt was destroyed and the other badly damaged, and the area destroyed was successfully captured by British troops. However, since then, the occupying troops from the 41st Brigade, including the 9th's sister Battalion, the 8th Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps, had been holding an exposed position very close to the German lines, and had been under very fierce attack in an uninterrupted bombardment. Their relief was due to take place on the night of 29th/30th July, by the 7th Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps and the 8th Battalion Rifle Brigade.

They had hardly done so, however, when they were subjected to intense attack. In addition to shell and mortar fire the Germans used liquid fire flamethrowers, described by 2nd Lt G V Carey of 8th Bn Rifle Brigade as "three or four distinct jets of flame, like a line of powerful fire hoses spraying fire instead of water". He further commented that: "Those who had faced the flame attack were never seen again".

The surprise and shock were complete and casualties were extremely heavy. The remnants of the British line fell back. Despite protest from the Brigade Commander, Brigadier Oliver Nugent, who wanted a complete Division to be brought up and a long artillery bombardment arranged beforehand, Divisional Command ordered 41st Brigade to counter attack at 2.45pm that afternoon, after only 45 minutes prior bombardment. But in view of the need for reinforcement, the 9th Battalion was called forward to assist, together with a Battalion from the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry.

At 12.30 pm the 9th Battalion moved forward and were in position ready to attack by 1.30pm. "B" and "D" Companies were in a communication trench north of the Menin Road and "C" and "A" Companies were in support south of the Road. The War Diary comments that "considerable losses were suffered while moving into these positions". Colonel Chaplin was with "B" Company.

The Regimental History describes what happened:

Preceded by its bombers, the two leading Companies, "B" (Tanqueray) and "D" (Durnford) each in two successive lines ... rushing the intervening 200 yards, carried the enemy's trenches at the point of the bayonet. In the act of directing his men to make good their success, [Lt Col] Chaplin came under machine gun fire and fell, shot through the head. Durnford and Tanqueray were also killed...

"C" Company (Young), next in succession, acting according to orders, moved diagonally to its right to cover the exposed flank of the two leading Companies; a flanking enemy trench was then rushed, and ... the Company was again led forward by its Captain in a further bayonet charge ... [But] the main attack had failed, and an overwhelming fire made further progress by "C" Company impossible. Many had fallen, but the arrival of "A" Company (Exell) in support enabled the survivors to make good the trench already gained, and to hold their ground.

The greatest gallantry was shown by the last-named company. Captain Exell himself went forward under heavy fire into the open and brought in Captain Young of "C", who was badly wounded; when going out again to assist a private Rifleman he was mortally wounded. Many other acts of heroism and self-sacrifice occurred by men striving under a murderous fire to rescue their wounded comrades lying in the open.

What remained of the Battalion was withdrawn that evening. According to the Battalion War Diary, Noel Exell died of his wounds the following day, on 31st July.

The Battalion that day lost five officers killed and five others wounded; two were reported missing in the Diary, subsequently recorded killed. The figures reported in the War Diary for other ranks were 49 killed, 236 wounded and 37 missing.

Hooge Crater was retaken by the British in early August 1915, but changed hands several times subsequently, being finally regained on 29th September 1918.

Commemoration

A short notice appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 6th August 1915:

Deaths: Exell - in France, from wounds received 31st July, Capt Noel Jardine Exell, 9th Kings Royal Rifles, age 24, only son of the late Rev J S Exell, for 20 years Rector of Stoke Fleming and formerly Vicar of Townstal, and grandson of the late George Parker Bidder, CE, of Great George St Westminster and Ravensbury, Dartmouth.

A longer obituary appeared the following week, including the following tributes from his Battalion:

Major Hope [himself wounded in the same battle and having taken command of the Battalion following Lt Col Chaplin's death] writing to Mrs Exell, says: "Your husband died a glorious death. He was mortally wounded after bringing in our wounded officer under fire, and while trying to help in a wounded rifleman. He was a most gallant officer and we all mourn his loss."

A fellow officer writes: "We have all been impressed by your husband's gallantry, and we have a fine example to follow"; and a Chapain attached to the brigade, in concluding his letter, says: "May we all have grace to be doing as bravely when our call comes".

The deceased officer lies near Hooge, in Flanders. A muffled peal was rung in his native village last Sunday.

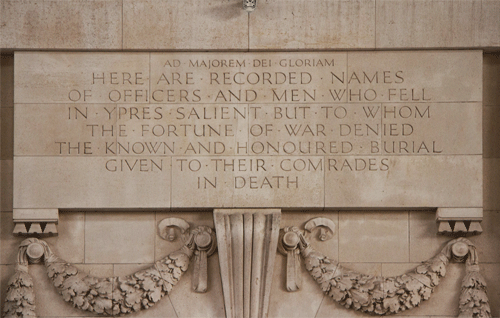

However, by the end of the war the site of Noel Exell's grave had evidently been lost.

He is also commemorated in the Charterhouse School Memorial Chapel.

Sources

George Parker Bidder, Grace's Guide to British Industrial History

Moretonhampstead History Society article on George Parker Bidder, 1806-1878

Dartmouth and its Neighbours: A History of the Port and its People, Ray Freeman, publ Richard Webb, 2007

A Brief History of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, 1755-1915, by Lt Gen Sir Edward Hutton, KCB, KCMG, publ 1917

Recollections of 2nd Lt G V Carey, 8th Bn Rifle Brigade, quoted in 1915, The Death of Innocence, by Lyn MacDonald, publ Penguin 1997

Charterhouse School Roll of Honour

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Exell |

| Forenames: | Noel Jardine |

| Rank: | Captain |

| Service Number: | |

| Military Unit: | 9th Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps |

| Date of Death: | 31 Jul 1915 |

| Age at Death: | 24 |

| Cause of Death: | Died of Wounds |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Second Battle of Ypres |

| Place of Death: | Hooge Crater |

| Place of Burial: | Menin Gate, Ypres |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | No |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | No |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Stoke Fleming War Memorial, Dartmouth Chronicle obituary |