Reginald Drake

Family

Reginald Ernest John Elliott Drake, known as Reggie, was born on 14th December 1898 in Brentford, Middlesex. He was baptised privately on 3rd January 1899 at the family home in 6 Stanley Terrace, and brought first to church at St Paul's, Brentford, on 4th November 1900. He was the eldest son of Ernest Drake and his wife, Ada Sheldrake. Ernest was Reggie's connection with Dartmouth - he was born in the town in 1870 and his parents, Reggie's grandparents, John and Mary Ann Drake, still lived in Dartmouth when Reginald was born.

Ernest was a blacksmith by trade. At the time of the 1891 Census, he was still living with his parents, and younger brothers and sisters, in Above Town, Dartmouth. On 11th February 1893, at St Petrox, he married his first wife, Emma Nora Mardon Scoble, of Bayards Cove. Emma was the daughter of John Scoble, a hairdresser, and his wife Florence. Emma was considerably older than Ernest, having been born in Dartmouth in 1858. Before her marriage she had worked as a domestic servant. Sadly, Emma died in Dartmouth in 1896. She and Ernest do not appear to have had any children.

Ernest left Dartmouth after Emma's death. On 30th July 1898, he married again, in St Paul's, Brentford, Middlesex; his address at that time was 33 Hamilton Road, Brentford. His second wife was Ada Leah Bond Sheldrake. Successive censuses indicate that she had been brought up in Norfolk, by her grandparents, William and Mary Bond. By the time of her marriage, she had moved to Chiswick, presumably to obtain work. However, the St Paul's marriage register does not record her occupation. Ernest was still working as a blacksmith.

By the time of the 1901 Census, Ernest and Ada lived at 6 Stanley Terrace, Layton Road, Brentford, with Reggie and a new baby, Olive Ada May, aged five months. Also living with them were Ernest's brother John William and sister Ella. John William worked as a boat builder; Ernest continued to work as a blacksmith. The following year, John William married at St Paul's, Brentford, and he and his wife remained in Brentford, close to Ernest and Ada.

Ernest and Ada's third child, Lawrence George, was born in 1902, and their fourth, Muriel Alice Irene, on 24th April 1904. The family was still living in Layton Road when Muriel was baptised on 5th June 1904, at St Paul's, Brentford. Sadly, Olive died aged three, soon after Muriel's birth. She was buried in Ealing and Old Brentford Cemetery on 31st November 1904.

At some point between Olive's death, and the birth of their fifth child, Ivy Ella Marguerite, in 1907, Ernest and Ada moved to Long Eaton, Derbyshire. At the time of the 1911 Census, they were living at 194 College Street, Long Eaton. Ernest worked as a foreman for a "Railway Wagon Builder", likely to have been the company S J Claye Ltd. Also living with them were his brother George, and another young man, Walter Fearn, both of whom worked for a railway wagon builder, presumably the same company. Reggie and the other children were still at school. Back in Dartmouth, Reggie's grandparents, John and Mary Ann Drake, ran a shop in the Newcomen Road, with their son Martin and daughter Ella (who presumably returned to Dartmouth from Brentford after Ernest and his family moved to Long Eaton). It is not known if Reggie ever visited his grandparents but the inclusion of his name on the Dartmouth War Memorial suggests that the family remained close.

On 8th August 1912, Ernest was admitted to the County Asylum, Derby. The admission register does not record the nature of his mental illness, but sadly he died on 13th June 1914, when Reggie was fifteen, and the youngest of the children, Ivy, was only seven. In 1916, Ada married again, in Shardlow, Derbyshire, to George Lowe.

Service

Reggie first joined the British Army on 22nd March 1915, attesting at Derby. He lived at 128 Granville Avenue, Long Eaton, and gave his age as 19 years 2 months, although he was in fact only 16 years 3 months. When he enlisted, he was working as a driller for a wagon repairer, presumably having joined the same company as his father. His service papers for this period have survived, so we know that Reggie attested as a private with the 2/5th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters, number 4167, being transferred shortly afterwards to the 3/5th Battalion, a training battalion.

Territorial Force units recruited from the age of seventeen and allowed those who volunteered to go abroad to do so after only a brief period of training. However, because of rising concern about under-age boys serving overseas, it was announced on 11th February 1915, shortly before Reggie volunteered, that the Territorials would come into line with the rest of the Army, and the age for overseas service would be raised to nineteen. This may be why Reggie added almost three years to his age. His papers show that he volunteered for overseas service on joining.

When or how it was discovered that Reggie was underage is not clear from the surviving papers; but on 29th October 1915, he was discharged "in consequence of having made a mis-statement as to age on enlistment". He had not been sent abroad - all his 222 days of service were "at home".

Although his discharge papers stated his military character to have been "very good", his conduct had not been flawless - he had missed a 6.30am parade on 27th July, and on 18th October, was confined to barracks for four days for "breaking the ranks and throwing dirt". Nonetheless the Commanding Officer of the 3/5th Battalion, based at Belton Park, near Grantham, declared that Reggie's conduct had been "satisfactory" and that he (the CO) had "received no complaints in regard to him". At the time of his discharge he was still only 5ft 3ins; the papers record that he had a "fresh" complexion, blue eyes and dark brown hair. He was discharged back to Ada's care at home.

In 1916 compulsory military service was introduced; the second Military Service Act of May 1916 made liable for military service all men aged 18-40 inclusive, single and married, although no-one would be sent abroad until he had reached the age of 19. The papers from Reggie's second and final period of service with the Army do not appear to have survived, so it is not known exactly when he joined up again. Although he may well have been conscripted, voluntary enlistment did not stop after conscription was introduced. For example, a study of sixteen surviving records of those in a draft of soldiers joining the front in June 1918, showed that ten had enlisted shortly before becoming eligible for call-up. But as Reggie passed his eighteenth birthday on 18th December 1916 and call-up generally took place at the age of 18 years and one month, it seems fairly certain that he would have rejoined at the latest by the end of January 1917. This time, he joined the Lincolnshire Regiment. According to Soldiers Died in the Great War, he lived in Mapperly Plain, Nottinghamshire, at the time of his enlistment.

Surviving papers of a soldier with a service number very close to Reggie's, and of a similar age, suggest that Reggie may have received his training in the 4th (Reserve) Battalion, at Saltfleetby, Lincolnshire. During the first half of 1917, the 4th (Reserve) Battalion was the training reserve for the 1/4th, 2/4th, 1/5th and 2/5th Lincolns; the Lincolnshire Regiment medal roll shows that Reggie was first posted to 1/5th Lincolns. When he first arrived in France is not known, although this should not have been before his nineteenth birthday, on 14th December 1917. By March 1918, he had transferred to the 2nd Lincolns, one of the two regular Battalions.

New Year 1918

Along with many thousands of his cohort of young men arriving in the front line after the introduction of conscription, Reggie entered the conflict at a turning point. The Soviet Revolution of November 1917 had taken Russia out of the war (although the final treaty took several months to negotiate). Almost all available German troops could thus be concentrated on the Western Front. However, the economic and social situation in Germany was increasingly difficult: the country faced starvation and raw materials were in very short supply; social unrest was growing; some political leaders were urging a negotiated peace. Furthermore, American forces were beginning to arrive on the Western Front - and in time the huge population and vast industrial capacity of the USA would more than balance the loss of Russia from the Allies. For the German High Command, an offensive early in 1918 on the Western Front was the last chance to break the deadlock.

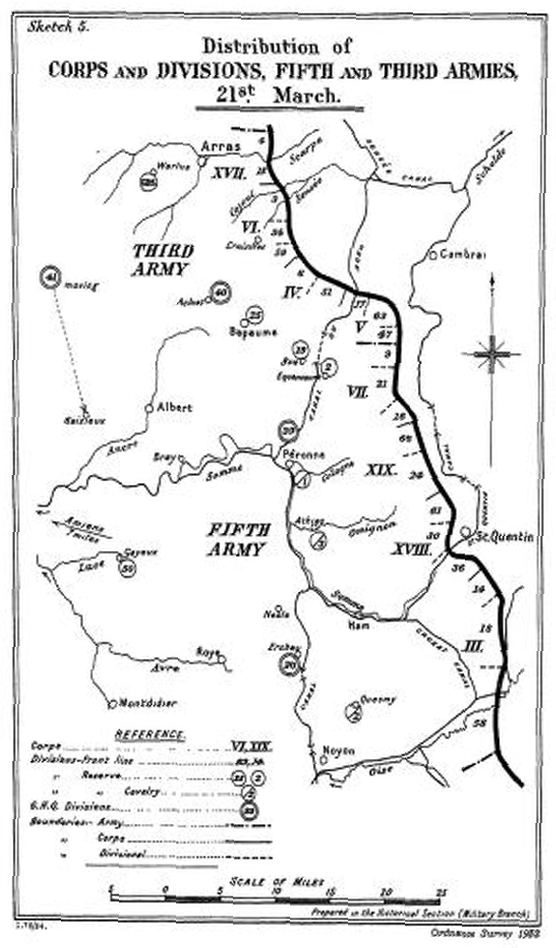

General Ludendorff considered a wide range of options, but in January decided that he would attack the British rather than the French. As for the options along the part of the Front held by the British, he decided that he would focus the first attack upon a stretch of the line between the River Scarpe in the north and the River Oise to the south. This was the sector held by the Third and Fifth Armies (the extent of line held by the British was extended from St Quentin to the Oise in January 1918).

The British expected a major attack on the Western Front. The Official History indicates that, at first, it was not clear where the attack would come, but that "from the beginning of March onwards evidence rapidly accumulated pointing to an attack being imminent between the Oise and the Scarpe". However, Peter Hart notes that intelligence available from RFC reconnaissance indicated by late January 1918 that a major attack would be made in this area. But it was still far from certain that there would not be other attacks elsewhere.

The 2nd Lincolns had begun 1918 near Passchendaele. On the night of 18th/19th January, the battalion left the front line to move to France, where they joined the 21st Division, 62nd Brigade. This was part of a major reorganisation of the BEF, due to restrictions imposed on the Army's requirements for manpower, in which many under-strength battalions were disbanded, so that men could be reallocated to bring other battalions up to establishment. Divisions were reduced from twelve to nine battalions and some battalions were reallocated to other divisions. The 62nd Brigade was reformed on 3rd February, and the following day the 2nd Lincolns joined the 1st Lincolns in the brigade (the remaining battalion was the 3rd/4th Queen's (Royal West Surrey)).

The Lincolnshire Regiment's History notes the challenges of this period:

The official despatches record the difficulties which these changes entailed; new methods in the tactical handling of troops had to be introduced, and to accustom subordinate commanders to these changed conditions was difficult, owing to the large amount of work which had become increasingly necessary on the defensive works. The expectation of a great hostile attack made the construction of new lines of defence behind the front-line system essential, and men could not be spared to go through the necessary training when out of the line.

As this illustrates, not only were there major organisational changes to deal with, but during these months, the BEF was in the process of implementing a radical change to convert from an offensive to a defensive force, to create "defence in depth" along the whole of the British front. In outline:

- Immediately facing the enemy was the "Forward Zone", based around the original front-line trenches. However, the lines were not generally held continuously, rather the defence relied on outposts and redoubts in the old third line, with interlocking fields of machine gun fire. The "garrison" was to be sufficient to "guard against surprise, to break up the enemy's attacks and compel him to … employ strong forces for its capture". But if the defence failed, "the value of the ground to be recaptured will seldom be worth the cost involved";

- Behind this was the "Battle Zone", about 3000 yards deep, intended to be the main battle ground. This was not a continuous line either, but had two or three systems of all-round trenches, with defences concentrated into key localities permanently garrisoned. Allocated troops would move forward from their camps to take their allotted positions if an attack was imminent, and surviving defenders from the Forward Zone would fall back to the Battle Zone. The aim was to stop any attack in this zone and to hold it. Should it be penetrated, "deliberate counter-attack must be launched at the first possible moment" to regain it (though if necessary, allowing time for coordination of two or more attacks);

- About 4-8 miles behind the Battle Zone was the "Rear Zone", but this was far less developed, especially in the Fifth Army area.

The artillery was also laid out in depth, with about two thirds positioned in the Battle Zone. Forward batteries had all-round protection and were, so far as possible, concealed.

Implementing this involved a massive construction programme all along the British line. Lieutenant General Gough's Fifth Army was particularly stretched - twelve infantry divisions held a forty-two mile front. Inevitably, as the Lincolns' history illustrates, there were not enough resources to hold the front line, while constructing the new defences fully and training the troops properly for the fast-moving response that would be expected of them when the attack came. Much of the area behind the Fifth Army front had been devastated firstly by the Battle of the Somme in 1916 and then by the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line in 1917. Consequently, the labour force available to the Fifth Army was heavily engaged in re-establishing essential logistic support rather than on building the new defences. Many units (the Lincolns were no exceptions) thus spent the period running up to the attack digging rather than training - work on the defences continued until the last moment. Even so, although the state of defences in the Forward Zone was "good" (according to the Official History) the Battle Zone was "still incomplete".

The new defensive arrangements were a radical change in tactics. The planned allocation of brigades and battalions to the Forward and Battle Zones varied not only because of local ground and territory, but also due to different views amongst senior commanders of the relative priority to be given to the Forward Zone and the Battle Zone. Many (including apparently General Gough himself) struggled with the idea of not fighting as hard as possible to hold the front line, and there was little experience in how to coordinate the two zones. The further apart the two zones, the more difficult it was to move resources between them. Not surprisingly, there were serious misgivings about the situation that would be faced by whichever battalion drew the short straw of the forward position on the day of the attack.

Furthermore, by the time the attack came, very little had been done in the Rear Zone, and in any case, reserves were limited. General Gough, aware of how stretched his forces were, wanted to bring up his two reserve divisions much closer to the Battle Zone to respond to any threatened breakthrough. But GHQ wanted the limited reserves in a position where they could be deployed anywhere along the line as the attack developed, so his request was refused and they remained in GHQ reserve.

21st March 1918: the "Kaiserschlacht"

According to the Lincolnshire Regiment's History:

The night of the 20th/21st March which preceded the great German attack was extraordinarily peaceful. Tension in the front-line trenches had for several days and nights been almost unbearable - there was an uncanny feeling of something in the air.

At 4.40am a massive German bombardment began, not just of the Forward Zone but well into the rear areas also. In the village of Nurlu, on the road to Peronne, Winston Churchill, at the time the Minister of Munitions, was staying overnight at 9th Division headquarters. He wrote later:

And then, exactly as a pianist runs his hands across the keyboard from treble to bass, there rose in less than one minute the most tremendous cannonade I shall ever hear … It swept round us in a wide curve of red leaping flame stretching to the north far along the front of the Third Army, as well as of the Fifth Army to the south, and quite unending in either direction … the enormous explosions of the shells upon our trenches seemed almost to touch each other, with hardly an interval in space or time … The weight and intensity of the bombardment surpassed anything which anyone had ever known before.

Seventh Corps formed the left wing or northernmost section of the Fifth Army front, connecting with the Third Army near Gouzeaucourt and extending south to just beyond Epehy, with three Divisions: the 9th (Scottish) to the north; the 21st in the middle; and the 16th (Irish) to the south. The position was on relatively high ground south of the Flesquieres salient, captured in the Battle of Cambrai. Any German attack would be expected to target the flanks of the salient to the north and south to pinch out the salient itself.

The Seventh Corps front was divided roughly equally between the three divisions. Each had one brigade in reserve. Of the six battalions thus left available to each division, the 9th and the 21st each had four in the Forward Zone, while the 16th had five. There were thus only five battalions in the Battle Zone in Seventh Corps' sector. However, the Forward Zone in much of this sector was relatively narrow and the front of the Battle Zone was in places only a short distance away. According to the Official History:

This strong manning of the Forward Zone was judged necessary on account of the short field of view of the high ground, on which the front had settled down after the Battle of Cambrai, and the ease with which the enemy could mass in the defile, through which the Schelde canal ran close at hand, free from ground observation.

But the risk was that strong manning of the Forward Zone would lead to very high losses in the event of a major attack of the sort anticipated, thereby rendering the task of holding the essential Battle Zone even more demanding.

21st Division's line ran from a position called "Chapel Hill" on the left, through Vaucellette Farm in the middle, to just south of the twin villages of Pezieres and Epehy on the right. 64th Brigade was in reserve. 110th Brigade held Pezieres and Epehy, which were well defended by a series of strong points. 62nd Brigade held the line from Chapel Hill to Vaucellette Farm. Vaucellette Farm, although in the Forward Zone, "was regarded as of special importance since it gave observation over the whole valley back to Heudicourt station, and had been designed as part of the main line of resistance" (Official History). Chapel Hill lies south of Gouzeaucourt, where several low ridges join. Though a small rise, it overlooked the whole Battle Zone area in this part of the front, so it was vital to hold it.

Although Chapel Hill does not appear to be marked on modern maps, Vaucellette Farm can be found north of Pezieres near the railway off the D89. It was garrisoned at the time of the attack by the 12th and 13th Northumberland Fusiliers. The defence of Chapel Hill was the responsibility of the 1st Lincolns, positioned in the Forward Zone in front of it.

2nd Lincolns received the order to "man battle positions" at 5.45am. C Company was allocated to support 1st Lincolns in the Forward Zone. A, B & D Companies were allocated to the front of the Battle Zone, on what their War Diary calls the "Yellow Line". No record has come to light detailing the Company in which Reggie served, so it is not known where he was located on the battlefield.

The 2nd Lincolns War Diary observes that moving into the required position that morning "was rendered excessively difficult owing to thick fog and heavy enemy gas shelling"; the 1st Lincolns report (prepared later "owing to the diary records from March 15th-21st having been captured by the enemy") similarly states that "Gas was used during the earlier hours of the bombardment and a heavy white mist made visibility extremely difficult". Most commentators appear to agree that the thick fog on the morning of the attack made it very difficult to mount an effective response to the attack, though accounts also show that it made things difficult for the attackers too.

Vaucellette Farm was the focus of a substantial attack and was overwhelmed after fierce fighting (the Lincolns' Regimental History times this at 10.00am although it may have been later). The 1st Lincolns Bn HQ, which was close to the Farm, pulled back behind Chapel Hill. The 1st Lincolns, with help from South African Brigade troops from the neighbouring 9th Division, were able to hold the hill. Their report of their action states:

D Coy [in front of the hill] held Skittle Alley and Tennis Trench protecting their right flank which was threatened from Vaucellette Farm. C Coy [to the left] held Chapel Street which was now severely attacked. A Coy in Cavalry Trench and Cavalry Support Trench [connecting the Farm to the hill] were outflanked by the enemy. Those that escaped made their way on to Chapel Hill, which was held throughout the day. A party of B Coy and C Coy of 2nd Lincolns formed a defence flank from Chapel Hill to Genin Well Copse [to the west of Chapel Hill]. 1st Bn HQ moved to a position north-west of Chapel Hill in Lowland Trench. The Battalion was reinforced by South African troops during the day and attempts by the enemy to bomb up the trenches at Chapel Hill were frustrated.

The Official History's account of the attack in this sector states that the front defences of the Battle Zone between Peiziere and the left of the 21st Division "held by elements of the 12th/13th Northumberland Fusiliers and 2 Lincolns were heavily attacked by two enemy divisions … The line was broken through between noon and 1pm … by 1.20pm the Germans had penetrated into the valley towards Heudicourt to a depth of over a thousand yards … [however] Field guns and machine guns had been placed to command [this] valley from north, south and west; 62nd Brigade was ordered to form a right defensive flank while 9th Division to the north had organised Revelon Farm. Thus, when the fog lifted, the [attackers were] pocketed in a veritable death trap". The advance was checked about 2pm and made "practically" no further progress "despite repeated efforts".

By their own account in their War Diary, 2nd Lincolns held their positions in the Battle Zone "all day against repeated attacks by the enemy". They were able to defeat an enemy group which moved around their left flank "under cover of a sunken road. A number were killed and the remainder (about 50) surrendered". This may be a reference to the circumstances described in the Official History. The 2nd Lincolns remained in position overnight; while 1st Lincolns close by were relieved about 3am by the South African Brigade. The 21st Division front was also reinforced by units from 64th Brigade.

In Epehy, most of the front-line troops in the Forward Zone had been withdrawn to the Battle Zone, in effect the twin villages, before the enemy advance began. A breakthrough to the north of Pezieres (part of the attack which overwhelmed Vaucellette Farm) was successfully resisted and despite fierce attack the Leicesters were able to hold the villages overnight.

But elsewhere along the Fifth Army front the Forward Zone had been overwhelmed by noon on 21st March. By the end of the day there had been serious losses in the Battle Zone in the centre and on the right of the Fifth Army front (the Third and Nineteenth Corps areas of the Essigny Plateau and the Omignon valley). Casualties were very high, around 38500 in total, of whom around 21000 were prisoners of war and around 7500 were killed; the worst day since 1st July 1916. But German losses were also very high, anywhere between 35000 - 40000, of whom around 10-11000 were killed.

General Gough, unable to secure reinforcements from the French (who still feared a similar attack on their own part of the front) and without significant reserves, decided that, although the front could be held "possibly for two or three days" without further reinforcement, the preferable course was an organised retirement to the forward line of the Rear Zone (the "Green Line") and if necessary, to the rear line along the Somme.

As the German advance continued, the 2nd Lincolns War Diary accordingly recorded a series of retreats on 22nd and 23rd March:

No change until 12 noon when orders were received to retire on Heudicourt … A & D Coys losing heavily in getting clear. Battn reformed in Heudicourt … About 5pm masses of the enemy were closing in on Heudicourt from two sides and orders were received to retire on Green Line at Gurlu Wood. Battn fought a rear-guard action with the enemy until nightfall when action was broken off. Battn then marched to its allotted position in the Green Line.

After quiet night enemy renewed attack about 8am. Battn received orders to retire from Aizecourt le Haut about 8.30am. During this retirement the CO was wounded … A line of trenches running parallel to the Nurlu-Peronne road were manned with left flank resting on road near junction of Nurlu-Moislains roads. The 1st Bn Lincs continuing the line to the left.

The position was maintained until 12 noon, when it became untenable through the enemy turning the flank. The retirement was continued, the Battn falling back on Haut Allaines in extended order where it was halted and reorganised. Practically the whole of the retirement was carried out under hostile shell and machine gun fire.

A new line was taken up on the high ground to NW of Haut Allaines but this was not maintained for very long and the Battn moved back to a line approximately midway between Clery [sur Somme] and Bois Marrieres [to the north of Clery]. The enemy pressure by this time had slackened and … the Battn took up a defensive position for the night.

Death

The Official History records that under the conditions prevailing on the night of 21st March, it was impossible for most units to prepare any reliable statement of their casualties. Battalions and companies had become mixed up, and many men reported missing returned later, having joined temporarily any unit they could find. Heavy casualties amongst officers and NCOs added to the difficulties. In many cases no reliable casualty returns were possible until much later, and then they covered a period of several days.

Casualty figures are first recorded in the 2nd Lincolns War Diary in the entry for 23rd March, when apparently the Battalion had sufficient time to begin to take stock, although it is not clear if the entry was actually written on that date. However, some attempt had evidently been made to assess the losses, because the War Diary reported that, by that time, and since the beginning of the offensive, "the Battn had dwindled to 6 officers and about 70 other ranks". But there is nothing in the War Diary to indicate the specific circumstances of Reggie's death and so far no other information has yet come to light.

An announcement of Reggie's death appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 5th April 1918, most probably placed by his grandparents:

DRAKE - March 21st - Reggie (Pte Lincolnshire Regt) the beloved eldest son of the late Mr Ernest Drake, and grandson of Mr and Mrs Drake, Newcomen House, Dartmouth, killed in action.

The officially recorded date for his death, as shown in the Chronicle, was 21st March 1918. He was nineteen.

Commemoration

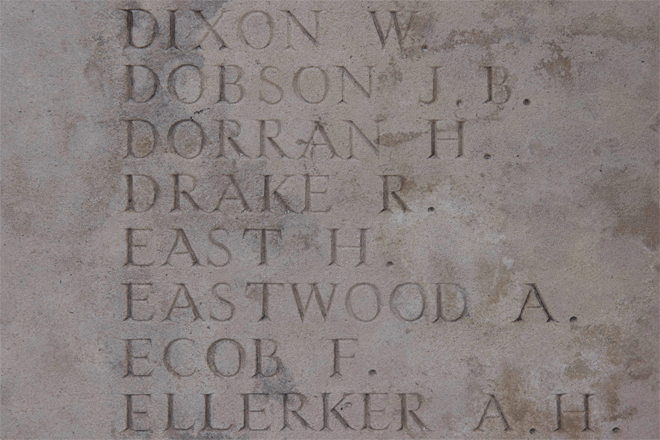

It seems that Reggie's body was never found or was not identified. His name appears on the Pozières Memorial, which "relates to the period of crisis in March and April 1918 when the Allied Fifth Army was driven back by overwhelming numbers across the former Somme battlefields, and the months that followed". He is one of nearly 8000 men named on the Memorial who died during the first four days of the fighting.

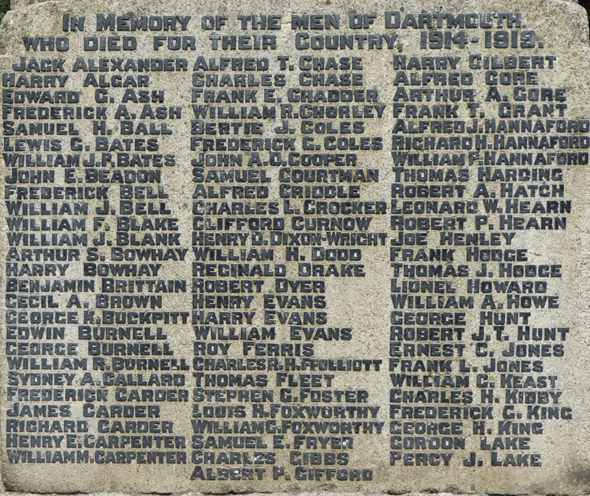

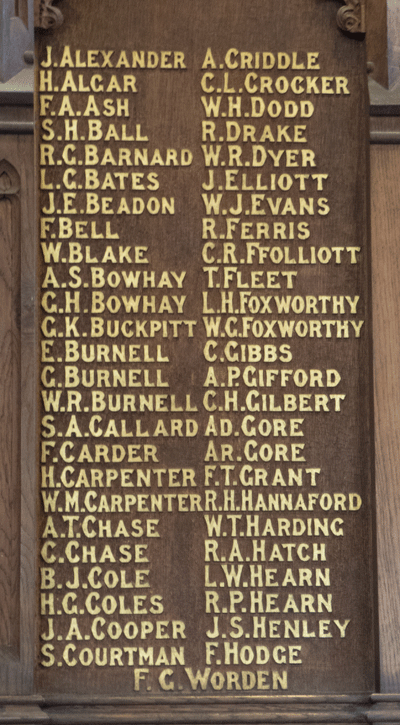

Reggie is commemorated in Dartmouth on the Town War Memorial and the St Saviours Memorial Board.

Reggie is also included in the Lincolnshire Regiment Roll of Honour (volume D-H) held in St George's Chapel in Lincolnshire Cathedral (known as the Soldiers Chapel).

Sources

Service papers for Reggie Drake in 1915 included in collection "British Army Service Records", series "WO 364 First World War Pension Claims", accessed through subscription website Findmypast.

Unknown Soldiers - A 1918 Draft, by Tim Lynch, from "Stand To! No 98", the journal of the Western Front Association, accessed on the website of the Western Front Association

War Diary of the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment Nov 1915 - Mar 1919, available at the National Archives, fee payable for download, reference WO 95/2154/1

War Diary of the 2nd Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment Feb 1918- Mar 1919, available at the National Archives, fee payable for download, reference WO 95/2154/2

The History of the Lincolnshire Regiment 1914-1918, by Major General C R Simpson, pub London, 1931. Accessed at archive.org

The History of the Great War: Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries, by Brigadier General Sir James E Edmonds, pub London, 1935. Accessed at archive.org

1918, A Very British Victory, by Peter Hart, pub Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 2009

Retreat and Rearguard Somme 1918: The Fifth Army Retreat, by Jerry Murland, pub Pen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2014

Reginald Drake's entry on the Lincolnshire Regiment Roll of Honour

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Drake |

| Forenames: | Reginald Ernest John Elliott |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 49905 |

| Military Unit: | 2nd Bn Lincolnshire Regiment |

| Date of Death: | 21 Mar 1918 |

| Age at Death: | 19 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | German spring offensive |

| Place of Death: | Near Epehy, France |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Pozières France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | No |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |