Henry Ernest Carpenter

Family

Henry Ernest Carpenter ("Harry") was born in Dartmouth and baptised in the parish of St Petrox on 24th March 1895. He was the youngest son of Richard Henry Carpenter and his wife Emily Sarah Marks.

Richard was not a native of Dartmouth, but came to the town as a young man. He was born in Morice Town, Devonport, in 1856, the youngest son of William and Betty Carpenter. William worked (appropriately) as a carpenter. He and Betty were from neighbouring parishes across the other side of the Tamar, St Germans and St Martins (near Looe). During their working lives they moved back and forth across the Devon/Cornwall border, but by the time of Richard's birth, they had settled in Devonport.

By the time Richard was fifteen, and although his parents were both still living, he had moved from Devonport to Dartmouth, to live with his elder sister Jane and her husband James Tapper. In the 1871 Census Jane, James and Richard were recorded living in Broadstone. James Tapper had joined the Navy in 1855 as a Boy 2nd Class, aged 14. Evidently he had some musical talent, for after reaching the level of Able Seaman, he had become a Royal Naval Bandsman (at that time bands were sometimes formed and paid for by Naval Officers for mess duties). He and Jane had married in 1868 and the following year he gained an appointment on HMS Britannia as a Cadet Servant. He became a Bandsman there in 1878 and finally retired in 1889.

Richard's occupation was recorded as "servant" in the 1871 Census; however, subsequently he became a mariner. He is likely to have worked on a variety of small merchant ships and pleasure vessels; in 1886, for example, he was recorded as a seaman and engineer on the crew of the steam yacht "Wild Rose", built in Lymington and registered in Bristol. The yacht at that time was owned by a Lieutenant George Colburne Higgins RN, of the Coastguard Service, based in Ireland - presumably he sailed into Dartmouth and needed a new crew member.

In the 1891 Census Richard was recorded still living with his sister Jane and her husband, who by then had retired from HMS Britannia. They lived in Cox's Steps, round the corner from Broadstone. In 1892, however, he married Emily Sarah Marks, at St Peter's, Stoke Fleming, and established a home of his own. Emily was the eldest of nine children born over twenty years to Richard Marks, blacksmith in Stoke Fleming, and his wife Sarah Elizabeth Prowse. Prior to her marriage, she had worked as a domestic servant in the house of Frances Reed, a widow, and her daughter Fanny, who lived in South Town, Dartmouth. Richard and Emily presumably therefore met in the town.

Richard and Emily had six children, all baptised in St Petrox parish, but only three survived infancy:

- Florence Emily, 1893: Florence died very soon after she was born.

- Henry Ernest, 1895

- William Marks, 1896

- Frederick George, 1901 (born 1900)

- Twins Albert Percy and Percy Albert, 1903. Percy Albert died before his first birthday, early in 1904, and Albert Percy died towards the end of 1904, aged 1.

Harry was thus Richard and Emily's eldest surviving son.

By 1900, Richard had given up the sea and become a "Coal Lumper". He had joined a hard trade, just at the point it began to decline. Dartmouth had become a coal bunkering station for ships in the 1870s and the trade had grown rapidly. Although the work was labour intensive, the trade worked on the basis of casual employment. Because there were always three or four companies competing to coal any ship, the coal porters or "lumpers" would wait "on the stones" hoping to be included in a gang employed to shift the coal. Coaling companies owned one or more standing hulks moored on the river. When a ship came into the harbour to coal, the lumpers would race to the coaling hulk in 6 or 8-oared gigs, kept moored against the quay wall. The winning gang would then load the coal from the hulk into baskets and lift these over the side into the bunkers of the vessel needing the coal.

From 1901 onwards, both the tonnage of ships coming into Dartmouth for coal, and the amount of coal shipped for bunkering, began to decline - ships became larger than the port could handle; more coaling stations were set up elsewhere; more efficient engines meant that ships needed less coal; and gradually coal itself was replaced by oil and diesel fuel. These changes led to sales, mergers and takeovers amongst the coaling companies, so that by 1912 there was in effect only one company, Evans & Reid, with a monopoly on the business. Wages had remained the same for twenty years; lumpers, who worked in gangs of 6-8, were paid on a piecework rate of 2d per ton. The transfer of 200 tons of coal from hulk to vessel, in practice a day's work, equated to a daywork rate (per person) of only 4s; and lumpers could not rely on being able to work every day. (This compares to (for example) a wage for a skilled agricultural labourer of about 15s per week with a cottage and garden provided).

Lumpers felt a growing sense of grievance about their pay and working conditions and early in 1914, after a visit from Ernest Bevin, they decided to form a branch of the Dock and General Workers Union. They then put their demand to the coaling companies for a wage rise to 3d per ton. This was rejected outright, so the lumpers went on strike. Evans & Reid advised customers to use their alternative facility at Portland, and the lumpers then called on men at Portland to "black" diverted ships in sympathy, which they did. Stalemate ensued. Eventually the men were forced back to work by poverty and hunger, without their claim being met. The Great War then intervened.

In these circumstances it is not surprising that neither Harry nor his brother William followed their father into the coal lumping trade. In 1911 the Census recorded the family living in Newcomen Road. Harry, by then 16, was working as a shop assistant in F C Walls & Co, in Lower Street, which was a tailors, clothing and shoe store. William, aged 14, was apprenticed to a painter. The youngest boy, Frederick, was still at school.

The Call to Arms

Harry's service number (11783) indicates that he joined up between 1st September and 5th October 1914, and this is consistent with the appearance of his name in a list published in the Dartmouth Chronicle of 11th September 1914 giving "the names of Dartmouth patriots who have responded to the National Call to Arms" and who had enlisted locally during the previous fortnight in "Lord Kitchener's Army".

Kitchener had accepted the post of Secretary of State for War on 5th August 1914, the day after war was declared. At that time he was one of the few who expected a long conflict. He had instantly taken steps to expand the Army, seeking Parliamentary approval on 6th August for the size of the Army to be increased by half a million men. On 7th August advertisements were placed in the newspapers for 100,000 men, and three weeks, later, for another 100,000. Over the next few weeks, and particularly as news reached home of the retreat from Mons and the hard fight facing the British Expeditionary Force, recruits flooded in.

In Dartmouth (according to the Chronicle of 4th September 1914):

An immense crowd assembled in the Royal Avenue Gardens last evening, when a public meeting, addressed from the bandstand, was held for the purpose of obtaining recruits for Lord Kitchener's Army. At a quarter to eight o'clock a procession was formed outside the Guildhall, and comprised the Mayor (Alderman C Peek) and the Corporation, who attended in State, a number of prominent townsmen, the Corporation Fire Brigade, and the Borough Band, which played martial airs. The flags of the Allies were borne aloft in the procession.

The crowd was addressed by various speakers, at some length, and more "martial airs" were played. Over forty recruits then stepped into the bandstand, each to great applause. The procession then returned to the Guildhall, with the recruits, to more applause from "dense crowds" along Duke Street and Victoria Road.

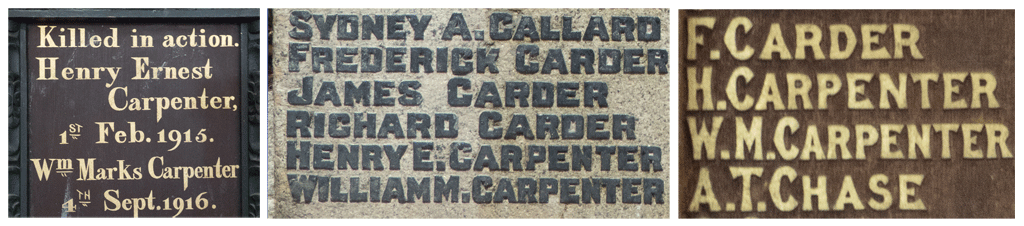

Harry's name appears seventh in the list of those who were reported to have enlisted in the edition of the Dartmouth Chronicle published after this occasion. It would seem his brother William also enlisted at very much the same time, as his name appears in a slightly longer list published the following week (also including Harry's name), on 18th September 1914. William joined the Devonshire Regiment and is also on our database - his story will be published in September next year.

Service

Harry and William were two of the 478,893 men who joined the Army in the recruiting boom between 4th August and 12th September. William either chose, or was allocated to, the 8th (Service) Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, which was formed at Exeter on 19th August 1914 as part of Kitchener's First New Army (K1).

However, because Harry either chose, or was allocated to, the Coldstream Guards, he did not in fact join any of Kitchener's New Armies. The Foot Guards regiments had decided that in order to maintain standards they would not expand on the scale of Line Regiments and raise battalions for Lord Kitchener's New Armies, nor did they have any battalions of the Territorial Force. In August 1914 the Coldstream Guards formed a Reserve Battalion at Victoria Barracks, Windsor, to train officers and other ranks joining the regiment. Recruits did an initial twelve weeks at the Guards Depot at Caterham and then went to Windsor for training in musketry, the Lewis Gun, trench warfare, and bombing.

All three battalions of the Coldstream Guards had gone to France in August 1914. Casualties had been heavy. Over 3000 men had originally landed in France and reinforcements of nearly 2000 had been added since, but after four months of fighting, losses totalled 2418:

| Battalion | Killed | Wounded | Prisoner | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 322 | 678 | 188 | 1188 |

| 2nd | 116 | 313 | 15 | 444 |

| 3rd | 193 | 581 | 12 | 786 |

(For the experience of 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards to October, see William Henry Howe on our database).

The 1914/1915 Star Medal Roll shows that Harry disembarked in France on 22nd January 1915. Although the Unit War Diary of the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards makes no reference to reinforcements, the Regimental History states that the 2nd Battalion received on 26th January 1915 a draft of about 199 men under 2nd Lieutenants Ashley, Carter-Wood, Pinto, and Pratt. Harry was a member of this draft. At this point the Battalion were in reserve, in billets at Les Choquaux, just to the north of Béthune, though "in readiness to turn out at a moment's notice".

Death

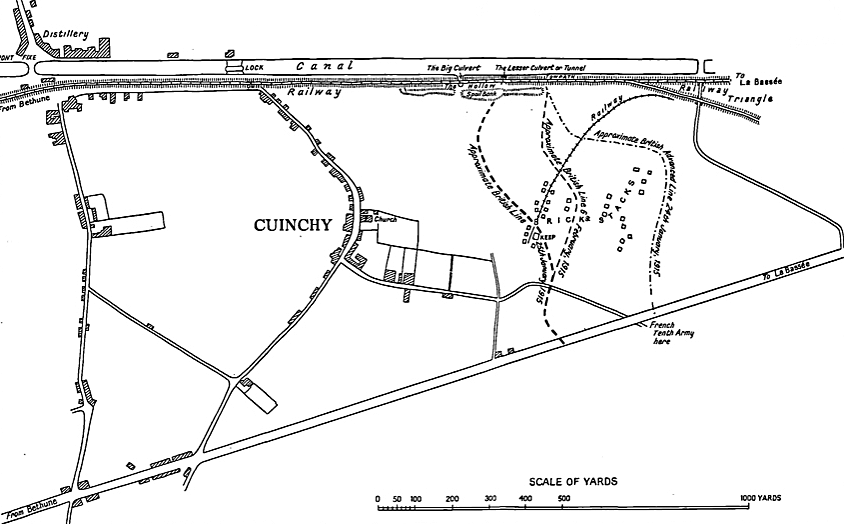

For the first three days of Harry's time at the front, things were quiet for his Battalion. They stayed in billets, turning out on parade each day, and, by way of staying "in readiness", marched to Essars one day and Gorre the next. On the evening of 30th January, however, they took over the trenches in the front line at Cuinchy, to the east of Béthune, from the Sussex and Northampton Regiments. Here Harry fought, and died, in a short and violent engagement, which took place two days later.

The front line at this point was 800 yards to the east of the village of Cuinchy. The village was bounded to the north by the Canal d'Aire and the railway, both running in parallel west-east from Béthune to La Bassée; and to the south, by the main road from Béthune to La Bassée. The point at which the British line touched the main road was the end of the British sector of the front, and where the British line met the French.

Flat ground to the east of the village, between the railway and the road, contained thirty or so brick stacks, which had been made just before the war. The stacks were about sixteen feet high. Most were behind the German front line. However, some of those behind the British line had been used to form what the Regimental History calls "a keep, or small redoubt", through which ran a partially prepared second line of defence.

A little further to the east was a triangle of railway lines, formed by a branch line coming up from Vermelles, to the south, to join the main east-west line. This "railway triangle" was held by the Germans, which gave them an advantage, since (in the words of the Regimental History) "it gave [the enemy] a fort which he could hold" - the embankments provided a good view over the otherwise low, flat ground, and also provided cover from rifle fire.

The position had previously been held by the 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards and 1st Battalion Scots Guards, half of them forward, in an advanced trench, and half holding the second line of defence. On 25th January a German attack was launched using mines, and the advanced trench was rushed. The British fell back to the second line of defence. Though they had suffered heavy losses, they were able to hold the "keep", and establish and hold a new line running through the "keep" from the canal and railway to the main road.

On arriving at the position at 7.30pm the evening of 30th January, 2nd Battalion Coldstream occupied the line, with the Irish Guards at Brigade headquarters in Cuinchy village in support and the 3rd Battalion Coldstream in reserve. 2nd Battalion deployed with No 1 Company on the right of the position, Nos 2 and 3 Companies in the centre, and No 4 Company on the left. Harry was a member of No 4 Company.

His Company's position was next to the canal and railway, in an area of ground known as "the hollow". The hollow is described in the Regimental History as a narrow strip of ground some four hundred yards long and about twenty yards wide, created by a long, narrow, spoil bank which ran parallel with the railway. It was connected with the towpath between the canal and the railway by two culverts under the railway, the "big culvert" (which was farther to the west) and the "lesser culvert". Both culverts were (just) behind the British line.

As a result of the attack on 25th January, the new positions of the German and British lines were extremely close. In particular, No 4 Company was holding a trench which was held at the other end by the Germans. Nevertheless, on coming into the position on 30th January, they were able to occupy it without difficulty, and on 31st January, though subject to sniper fire, they were able to erect a barricade for some protection.

However, at 2.30 am on 1st February, No 4 Company were attacked by bombs (grenades), and were forced to evacuate their end of the trench. They moved back behind a second barricade of sandbags positioned across the Hollow, between the two culverts. The "lesser culvert" was now behind the German line, but as they still held the "big culvert", the Coldstreams still had access to and from the tow-path.

No 4 Company Irish Guards came up in support and a counter attack was organised, which took place about 4.00 am. The attack was made in three lines: the first, by a small party up the tow-path; the second, by a larger group up the Hollow on to the railway embankment; the third, against two barricades now erected by the Germans to protect their new position. But the counter-attack suffered serious losses. Men on the railway embankment were easily targeted by machine guns; while the ground in the Hollow was cut up with communication trenches and dugouts. This prevented any rapid charge being made, while men moving slowly across the various obstructions presented "a fine target" in the moonlight. Colonel Pereira (Commanding Officer of 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards) therefore cut his considerable losses and recalled the attack at 6.30 am, before dawn made things even worse.

A further counter-attack was then ordered, but this time with artillery preparation. The position to be recaptured was subjected to intense bombardment for ten minutes, beginning at precisely 10.05 am. The vivid description in Colonel Pereira's diary is quoted in the Regimental History:

It was a sight never to be forgotten. [Our guns] poured high-explosive shells into a comparatively small area with astounding accuracy and enormous effect. The word awful describes it, when one pictures living men in the midst of a perfect hell of explosions. I saw one body lifted on to the embankment, another evidently fearfully mangled was hurled right over the embankment and tow-path into the canal - a sight that would sicken one in cold blood; but our losses had been heavy and the place had to be retaken, and the relief of seeing the effect of the bombardment made one pleased, horrible though it may seem.

The counter-attack was then launched at 10.15 am. Once again No 4 Company was to advance up the tow-path and up the hollow; following was a bomb-party from Nos 3 and 4 Companies, then 30 Irish Guards with sandbags, spades, and more bombs, accompanied by a party of Royal Engineers, to consolidate ground won; and finally, a further company of the Irish Guards in reserve, to hold the existing British position.

Colonel Pereira's diary continues:

... I loosed the attack and they streamed up to the first [German] barricade. A few gallant Germans still showed fight and and were shot down. [Captain] Leigh-Bennett [of No 4 Company], seeing the advantage of pushing on to the apex of the hollow and so advancing on our original front lost this morning, urged that the Irish Guards holding the second [British] barricade [in reserve] should be pushed in, which was done, and the front line strengthened by them advanced to the end of the hollow. Our bomb throwers did most excellent work; they were cool, plucky and most effective, and greatly assisted in overcoming the last resistance of the Germans ... On gaining our present line the Irish Guards took the apex of the hollow and ... put it into a state of defence assisted by the Royal Engineers. The hollow was a perfect shambles, mangled corpses and a few wounded.

The attack involved several acts of great courage. Lance Corporal Michael O'Leary of the Irish Guards won a VC, for the single-handed capture of a German machine gun and two prisoners; while four members of 2nd Bn Coldstream were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. The action was successful in recovering the ground that had been lost earlier in the morning. In addition, the capture of the position at the eastern end of the hollow enabled the capture of two further trenches held by the Germans, which were abandoned (according to the Regimental History) "in such a hurry that [the enemy] left his rifles behind still leaning against the parapet".

At about 8-9 pm the Battalion was relieved by the 3rd Battalion Coldstream, and marched to billets in Béthune, for two days rest. Subsequently on 6th February a further attack was mounted at the position, this time involving the 3rd Battalion Coldstream and the 1st Battalion Irish Guards, which was able to retake the brickstacks immediately in front of "the keep", and recover a little more ground, though not quite as far as the line lost on 25th January. The position reached on 6th February 1915 then remained much the same for the rest of the war.

Harry, as a member of No 4 Company, must have been in the thick of the fighting. On 12th February, the Dartmouth Chronicle published the following news:

We regret to have to record the death in action of a Dartmouth soldier, Private Harry Carpenter, son of Mr and Mrs Carpenter, Newcomen Road. Deceased enlisted just after the outbreak of war, when he was an assistant in the employ of Messrs F C Walls & Co, Lower Street. In a letter to his parents, Mr and Mrs P Blake, Mount Galpine, Dartmouth, Private C Blake, of the Coldstream Guards, makes reference to the death of Private Carpenter.

Charles Ernest Blake, the son of Peter and Anne Blake, had joined the Coldstream Guards in 1913 and was in No 1 Company, 2nd Battalion. He survived the war, being discharged on 4th April 1919, following a gunshot wound. He was a year older than Henry. In 1911 he and his family lived in Newcomen Road, where Henry and his family also lived.

Guardsman Blake wrote:

I saw Harry Carpenter two days after he joined our battalion when we were in reserve behind the trenches and the following day when we went into the trenches. No 4 Company made a charge at the Germans and captured their trenches, and poor Harry was killed, which I am very sorry to tell you... It was something terrible. I think we lost about fifty altogether, dead and wounded. Poor Harry was shot in the back; it was instant death. They buried him behind the trenches.

If this is accurate, it suggests that Harry was killed during the second, successful, counter-attack, though most of the losses were incurred during the initial German attack and the first, failed, counter-attack. The total casualties were higher than Private Blake's figure. According to the Regimental History, the 2nd Battalion's losses were:

- Killed: 2nd Lt J A Carter-Wood, who had accompanied Henry and the other reinforcements to the front only a week or so earlier, and 21 rank and file. Another officer, Captain Thomas Knox (styled Lord Northland), was killed after the attack by sniper fire.

- Wounded: 51.

The Irish Guards lost two officers killed and three wounded, and 32 rank and file killed and wounded.

Harry had been in France ten days, and in the front line for just two days, when he was killed.

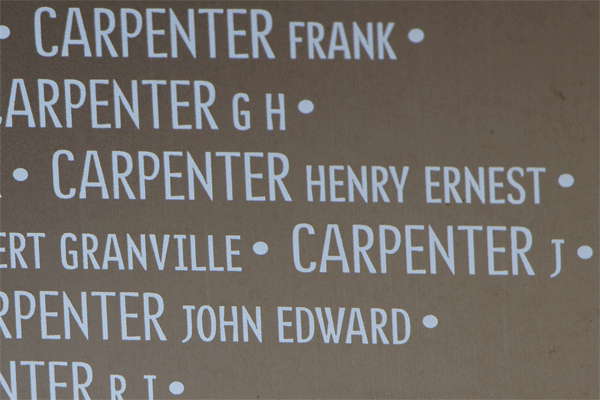

Memorial

Although Charles Blake's letter to his parents said that Harry was buried behind the trenches, it would seem that his grave was either not found, or could not be identified, since he is now commemorated on the Le Touret memorial. This memorial commemorates British soldiers killed in this sector of the Western Front from the beginning of October 1914 to the eve of the Battle of Loos in late September 1915 and who have no known grave. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database, four others from 2nd Bn Coldstream Guards who died on 1st February 1915 are also commemorated at Le Touret. There are also several burials in the Cuinchy Communal Cemetery of members of the Coldstream Guards who died on that date, including 2nd Lt Carter Wood and Captain Lord Northland.

As one of the 579,206 casualties in the region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Harry is also commemorated on the new memorial at Notre Dame de Lorette, "The Ring of Memory".

Harry's parents placed a brief announcement of his death in the same edition of the Dartmouth Chronicle in which Charles Blake's letter appeared. The announcement read:

"Killed in action, on February 1st, Henry Ernest, the beloved son of Richard and Emily Carpenter, aged 20 years".

Harry's name appears on the St Petrox Memorial, the Dartmouth town War Memorial, and the St Saviour's Memorial Board:

Sources

Naval Service record for James Tapper available for download from National Archives (fee payable), references ADM 139/246/24573 and ADM 188/35/58275

War Diary of 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards 1914 August to 1915 July, National Archives reference WO 95/1342/2 (available to download, fee chargeable)

The Dartmouth Bunkering Coal Trade, by Ivor H Smart E Eng, MRAeS, MIEE

Second to None: The History of the Coldstream Guards 1650-2000, ed Julian Paget, publ 2000, Pen & Sword Books

Regimental History: The Coldstream Guards, 1914-1918 volume 1, by Lt Col Sir John Foster George Ross-of-Bladensburg, publ OUP, 1928, available online:

The History of the Second Division 1914-1918, by Everard Wyrall, Vol 1 1914-1916, publ Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1921

Commonwealth War Graves Commission newsletter, February 2013, The Coldstream and Irish Guards at Cuinchy, by David Tattersfield

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Carpenter |

| Forenames: | Henry Ernest |

| Rank: | Private |

| Service Number: | 11783 |

| Military Unit: | 2nd Bn Coldstream Guards |

| Date of Death: | 01 Feb 1915 |

| Age at Death: | 20 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Cuinchy 1st Feb 1915 |

| Place of Death: | Cuinchy, France |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Le Touret Memorial, France |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | Yes |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | No |