Arthur ("Jack") Alexander

Arthur Alexander, known as "Jack", was born in Twickenham, Middlesex. According to his naval record, his date of birth was 9th April 1881. His father, Edward Alexander, was also born in Twickenham, in 1853; his mother, Ellen Jane Perring, was born in Dartmouth in 1852. She was the daughter of John Perring and Ann Maria Harris; John was a mariner and by the time of the 1881 and 1891 Census, the Master of the Steam Tug Hauley (an ancestor of today's Lower Ferry). Ellen's brother, another John, was the stepfather of Lionel Howard, and her younger sister, Emily, was the mother of Frederick Pym, both of whom are on our database.

According to their 1911 Census return, Edward and Ellen Jane married in 1870; however, according to the 1871 Census, Edward Alexander was at that time living with his family in Twickenham, unmarried, and Ellen Jane (shown as Jane), was also unmarried, working as a servant in Dartmouth for Commander George Heather and his wife Elizabeth, in South Ford Lane. How Edward and Ellen Jane met is not known, but their eldest son Edward was born in Twickenham in (or around) 1872. The 1911 Census recorded that the couple had twelve children, four of whom had died; surviving were seven boys, of whom Jack was the fifth in line, and one girl, Minnie.

In the 1881 Census Edward was recorded as a bricklayer's labourer and, presumably to find work, the family moved around the country. From Twickenham they moved to the North-East, where Charles was born in Warrenby and Alfred in Middlesbrough. By the time of Frederick's birth in 1880 the family were back in Twickenham, where Jack, Herbert and Frank were born; and sometime before Minnie was born in 1886 (based on Census ages) the family moved back to Dartmouth. In the 1891 Census the family were recorded living in Higher Street, Dartmouth. Edward (senior) was working as a "General Labourer". The oldest boy, Edward, was no longer at home, having joined the Cheshire Regiment, aged 14, as a musician, five years earlier. Charles and Alfred were both working as errand boys. The other children, including Jack, were at school or at home.

In 1901 Edward and Ellen were still living in Higher Street but Edward was no longer a labourer. Instead he had become a "stoker on a steamship". Perhaps this was due to the influence of his father-in-law, John Perring, now retired, who had come to live with his daughter following the death of his wife. Several of the boys followed their grandfather to sea - Charles was working as a yacht steward, Frederick as a boatman, and Alfred and Jack went into the Navy. Alfred had joined HMS Impregnable, the boys training establishment at Devonport, on 7th November 1894, beginning a twelve year engagement on 1st December 1896. Jack followed three years later, though as his occupation prior to joining was "blacksmith's labourer", and he joined as an adult, aged 18, it perhaps took him a little while to make up his mind.

Service

Jack joined the Navy on 16th September 1899 as a Stoker 2nd Class. The Navy was much in need of Stokers and the requirements for this rating were not onerous:

- over 18 and "a desirable man for the Service"

- fit for the rating

- able to read and write fairly.

His naval record tells us that he was 5ft 6 1/2ins, with black hair, hazel eyes, and a "fresh" complexion.

After his initial training in the Royal Navy barracks at Devonport he was appointed to HMS Renown, at this time the flagship of Admiral Sir John "Jacky" Fisher, then the Commander in Chief of the Mediterreanean Fleet. After Fisher completed his tour, Renown continued in the Mediterranean until she returned to Portsmouth for a special refit in order to take the Duke and Duchess of Connaught on a royal tour of India, from November 1902 to March 1903 (the Duke of Connaught was the seventh child and third son of Queen Victoria).

Jack was then (after a period ashore) appointed to HMS Defiance, the Navy's torpedo school at Devonport. In October 1904 he was appointed to HMS Monmouth, which at that time was a modern armoured cruiser, having been completed only ten months previously, and assigned to the Channel Fleet. Perhaps he found naval discipline a little irksome, for his naval record states that, during his time on Monmouth, he spent 14 days in the cells, but gives no details about the reason.

HMS Monmouth transferred to the China Station in 1906, but Jack did not go with her, as he was assigned to HMS Hogue in May of that year. He joined on 3rd May 1906, just missing his brother Alfred, who the day before had left HMS Hogue for HMS Cambridge. HMS Hogue had been in China, but in 1906 became the boys training ship for the 4th Cruiser Squadron on the North America and West Indies Station. During his time on Hogue, Jack apparently came to the conclusion that the Navy was not the right walk of life, as he bought himself out of the Navy on 27th June 1907. Nonetheless, he decided to join the Royal Fleet Reserve, which offered a retainer and gratuity.

Neither HMS Monmouth, nor HMS Hogue, survived even the first year of the war; HMS Monmouth was sunk in November 1914, at the Battle of Coronel, with the loss of eight men from Dartmouth, and HMS Hogue even earlier, in September 1914, in the Channel, with heavy losses, including many Dartmouth cadets (see our article Dartmouth Cadets and the First World War).

Jack decided on a different career altogether. He moved to London, and became a police officer. The 1911 Census recorded him at Camberwell Police Station, in London, together with about twenty other constables and five prisoners. The reason for his move to London, and perhaps also for him leaving the Navy, was possibly connected with Susan Wills, whom he subsequently married. Susan came from Marldon, near Torquay. She was born around 1884, the daughter of Albert Wills, a stone mason, and his wife Susan Elizabeth White. By 1901 Susan (junior) was a housemaid at Marldon House, the home of Colonel Robert MacKenzie and his wife Augusta; and in 1911 she was a parlourmaid, working in the home of Edward Moon, retired barrister and his wife, at 6 Onslow Gardens, South Kensington.

Jack and Susan married only a few weeks before the outbreak of war, on 20th June 1914 at Camberwell St Giles. Her brother and sister Albert and Alice were the witnesses. Their married life lasted only three weeks, for on 13th July 1914 Jack was "test mobilised" as Stoker 1st Class to HMS Jupiter, a Majestic-class battleship; and on 2nd August 1914, he was appointed for real to HMS Majestic.

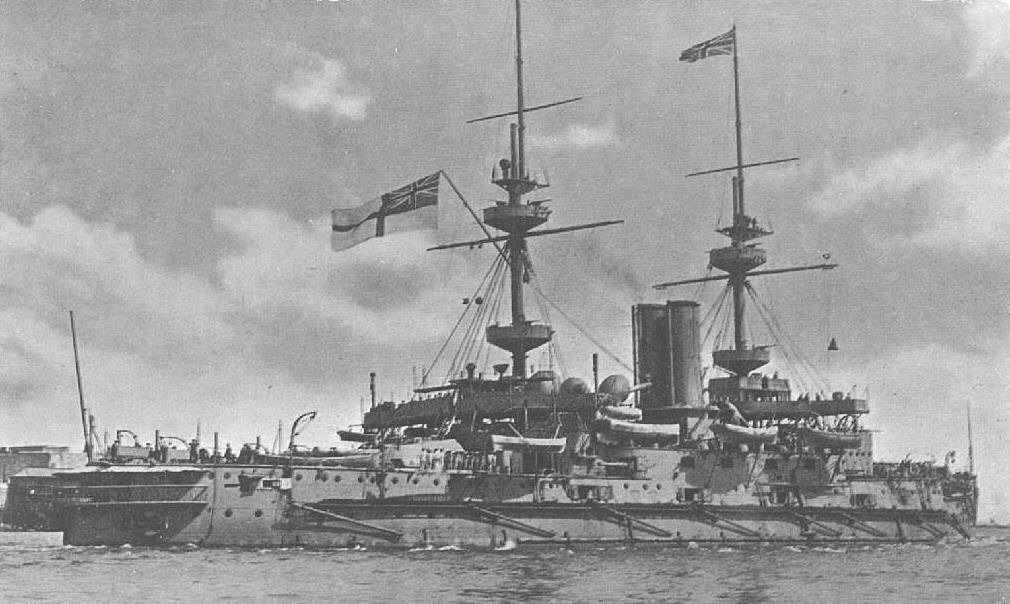

HMS Majestic

HMS Majestic was a pre-dreadnought battleship, the lead ship of her class, and at the time of her launch in 1895, the largest battleship ever built. By 1914, however, she was in the Third Fleet - older ships not far from obsolete, maintained by a small nucleus crew only, and designed to be brought into service in emergency crewed largely by reservists - like Jack.

Majestic's war was, to begin with, uneventful. She and the rest of her squadron were assigned to the Channel Fleet. She covered the passage of the British Expeditionary Force to France and in October escorted the first convoy of Canadian troops. She then spent a brief time as the guard ship at the Nore and then at the Humber, the nearest secondary base to Wilhelmshaven, where the German High Seas Fleet was based. In December she joined the Dover Patrol, which aimed to prevent enemy ships entering the Channel. Several times she was nearly deployed on planned operations against Belgian ports, but for one reason or another, these did not come to pass.

In February 1915, however, she was assigned to the Dardanelles Fleet, sailing with HMS Irresistible on 1st February. She arrived on February 25th as the Fleet resumed its bombardment of the outer defences of the Straits (see our Gallipoli timeline). On 26th February, she was involved with HMS Albion and HMS Triumph in the bombardment of Fort Dardanos, on the Asiatic side of the Straits, during which she received a hit below the water-line from the concealed batteries on the shore. The hit caused a leak, but was not otherwise serious. On 1st March the bombardment was repeated, and again the ships involved, including the Majestic, were hit by the shore batteries, although not seriously.

On 4th March Majestic covered the landing of Royal Marines to complete the survey and demolition of the outer forts, and under her fire "the main body of the enemy fell back". However, once again she was hit by shell fire. Between 5th- 8th March, she was involved in the first attempt to bombard the inner forts, in a supporting role.

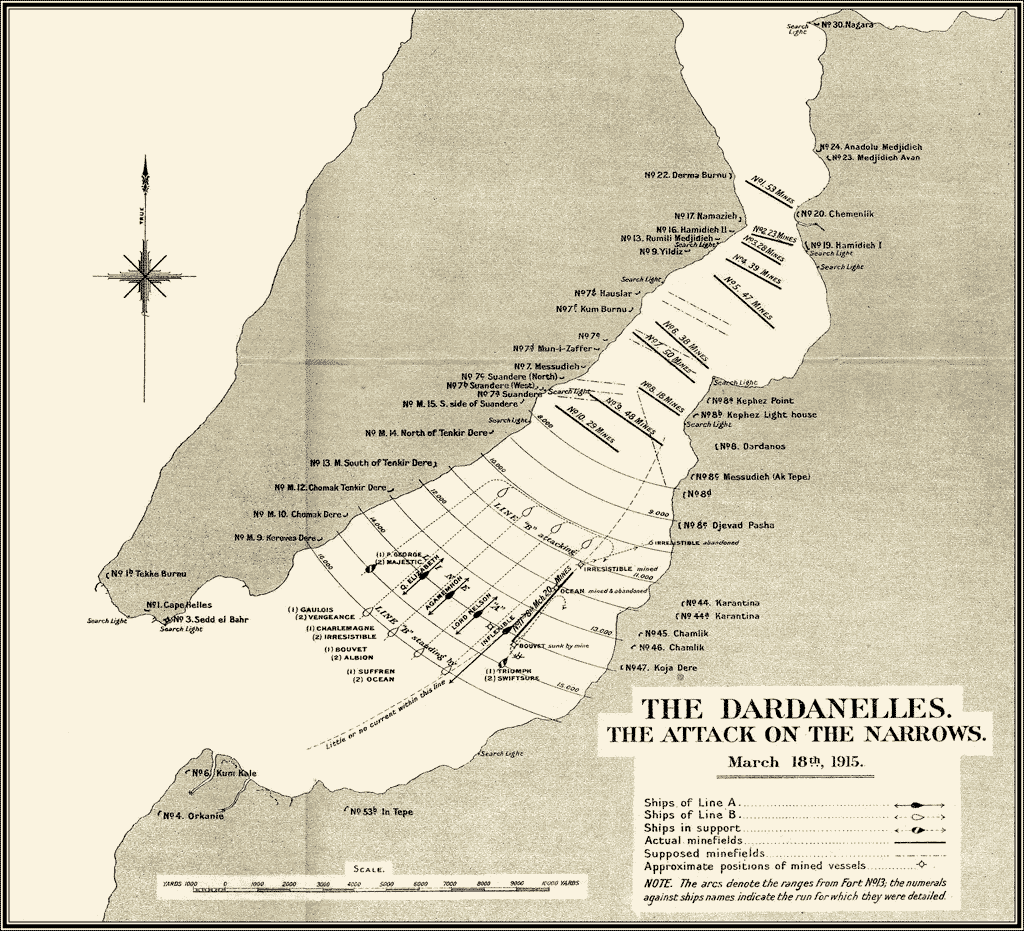

On 18th March, she participated in the all-out naval attack on the forts in the Narrows.

The ships were in three lines. The first line (line A) was to engage the principal forts on both banks and carry out long-range bombardment. The second line (line B) was to carry out closer action. The third line, which included Majestic, was to relieve the first and second line after four hours; Majestic's role was to relieve the Prince George and the Triumph.

The attack failed. The French battleship Bouvet, together with HMS Ocean and HMS Irresistible, were sunk by a new and undetected line of mines laid ten days earlier. In addition, HMS Inflexible, and two other French ships Suffren and Gaulois, were badly damaged, and so the attack was called off. The loss overall was severe, as it amounted to a third of the sixteen capital ships engaged. But Majestic, on this occasion, was fortunate.

The focus of the overall Dardanelles campaign then shifted from a purely naval operation to the planning of the land attack with naval support. In the meantime, Majestic was involved in continuing to patrol the shore, firing on Ottoman positions where necessary, to ensure that such gains which had been made were preserved, so far as possible. She was also involved on 18th April in an operation to destroy the British submarine E15, which had grounded, to prevent it falling into enemy hands.

For the landings, Majestic was assigned to the covering squadron for the Anzacs at Gaba Tepe. In the words of the naval history:

"each section had its covering ship, which, after leaving her boats with the attendant ships, moved to her assigned position - the Triumph, 2,600 yards west of Gaba Tepe for the right, the Bacchante about a mile from the centre landing-place, and the Majestic to the northward, a mile off Fisherman's Huts, to prevent the approach of reinforcements".

From there she could command the roads approaching the landing site. Though opposed, the initial landing was successful; but the Anzacs were subject to incessant counter-attack from Ottoman forces. When reinforcements arrived in the afternoon, Majestic's fire, directed by a sea-plane, enabled them to be pushed in to save the position. The naval history continues: "From then till midnight, the exhausted seamen toiled on to get men and stores ashore, and at the same time to evacuate the wounded, of whom at one time there were 1,500 on the beach".

After the landings, the battleships' role was to ensure that supplies and men could be safely delivered by keeping in check the heavier guns being brought into action by Ottoman forces against the beaches and inner anchorages. Majestic bombarded Ottoman positions on several occasions.

On 9th May Jack Alexander wrote a letter home, which appeared in the Dartmouth Chronicle after his death. In it, he attempted to reassure his parents about what they might have read about the operation overall and the damage to the ship, and also about how he was:

I am very pleased to say I am still in the pink of condition, although it is a terrible strain day after day, but still we stick it in the best of spirits, and from what I can see of it, it is of no use to be any other way. We have a nice mandolin band, and we cheer the boys up with a nice sing-song almost every night, so it helps to kill the monotony a bit - in action by day and sing-song by night... S [presumably his wife Susan] tells me in her letter that we have been seriously damaged by the Turks' gunfire, and driven off, but you need not worry, it is nothing serious; we can't expect to be bombarding day after day without being hit, so whatever you see in the papers from a German or Turkish source, do not believe it, until you see it officially announced by the Admiralty. The only damage we have sustained is four hits from shells, which we have repaired ourselves, and six or seven wounded. One died of his wounds, and one died whilst engaged torpedoing our submarine which ran ashore, so that it would not fall into the hands of the Turks. It was a very clever bit of work, as they were exposed to a very heavy fire from the Turks, and to tell you the truth I did not expect to see them come back again ... I daresay by the time you receive this the papers will be full of news concerning the landing of our troops here. It was a marvellous piece of work, and I can assure you we are giving the old Turks beans, and I am of opinion we shall soon be at Constantinople. It is very exciting to be up on deck watching them. Last night we gave them a good bombarding that they won't forget for a little while ...We must all trust in Providence and I stick it like a brick ...Good night, God bless you all, till we meet again.

Happy as a Berkshire pig.

With the benefit of hindsight, the irony is painful.

Death

On 25th May, HMS Triumph was off Gaba Tepe to protect the Anzac landing site, when at 12.25pm she was torpedoed by German submarine U21, which had left Wilhelmshaven a month earlier. Most of her officers and men were saved, for she was surrounded by other craft - indeed, the destroyer Chelmer had been patrolling round her precisely because of the submarine threat, and took up the majority.

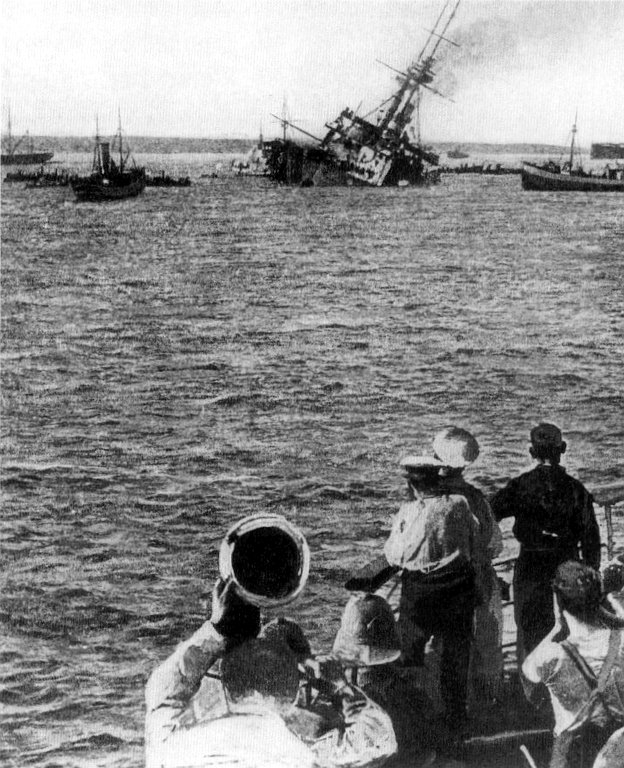

Additional precautions were taken, but the following day was quiet. A search for the enemy submarine failed to find anything - for after hitting HMS Triumph, U21 had dived under the sinking battleship to escape the destroyers looking for her, and spent the next twenty-eight hours on the sea floor. On 27th May, the Majestic was positioned in the midst of transports off-loading stores at W beach at Cape Helles, as close inshore as possible, while still being able to command the enemy's principal positions. She had anti-torpedo nets out as further protection. Beyond the transports was a destroyer patrol, and in the entrance to the straits was a cordon of unarmed trawlers.

But submarine U21 struck again: "At 6.45am a periscope broke the water no more than 400 yards away on the Majestic's port beam. She opened fire immediately, but not before the track of a torpedo was seen coming through one of the few gaps in the surrounding screen of transports... Striking the nets the torpedo went clean through them without a check and took its target fair amidships. Another followed instantly".

According to the official history, Majestic capsized in seven minutes. However, all the officers, and nearly all the men, were saved. The figures given at the time by the Admiralty for the Navy were two killed and 45 missing believed dead, as well as two civilians of the canteen staff. The naval history comments that those who died "were killed by the explosions or became entangled in the nets". The ship did not sink, but as she was in shallow water, lay resting on her foremast, with her upturned hull visible. She remained visible for many months.

Commemoration

On 28th May 1915 the Dartmouth Chronicle reported the loss of the Majestic, observing that: "The Dartmouth Roll of Honour includes the name of W Cranch, HMS Majestic". As this shows, the newspaper attempted to assess the local impact of events by referring to the lists it had published since the beginning of the war, and was adding to every week, of those serving in HM Forces. But as a source of information it was far from perfect, as the lists were not complete. Further, when many were saved, as in the case of the Majestic, it took a little time for official sources to issue final casualty lists.

On 4th June 1915, the newspaper further reported that:

In the official list of members of the crew of HMS Majestic who are missing and believed to be dead, is included the name of A. Alexander, of Dartmouth, 1st Class Stoker. Deceased, who was 34 years of age, was a son of Mr and Mrs C (sic) Alexander, Clarendon House, Clarence St. He was married only about a month prior to the outbreak of war. He was a Naval Reservist, and at the time of the mobilisation of the Fleet was in the Metropolitan Police Force.

The newspaper then quoted the letter from Jack to his parents, as above.

Finally, it continued:"The name of W Cranch, of Dartmouth, able seaman, HMS Majestic, appears in the list of survivors".

Also appearing in that edition of the newspaper was a family announcement:

In Memoriam

The following week further announcements were placed by the family:

In Memoriam

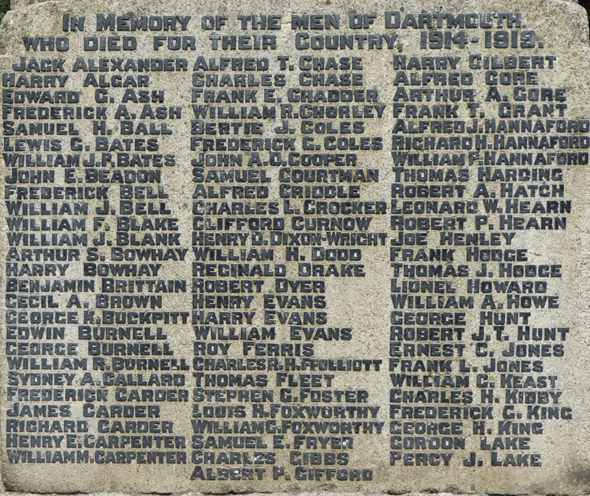

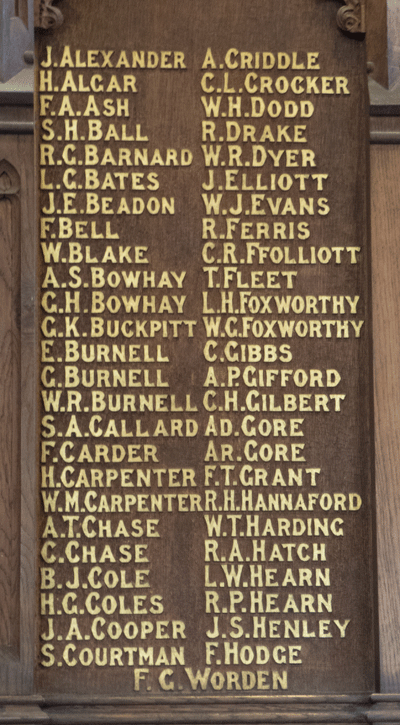

Jack is commemorated on the Town War Memorial and on the St Saviour's Memorial Board as "Jack" and "J" Alexander, rather than in his given name of Arthur.

Like all those lost at sea who sailed from Devonport, he is commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial, in the name of "A Alexander".

Jack's brother Alfred, who had remained in the Navy after Jack left it, and was still serving at the outbreak of war, survived it. He had been seconded to the Australian Navy in 1913 and remained on HMAS Melbourne for most of the war.

Their father, Edward Alexander, died in 1918 and was buried in Longcross Cemetery. Ellen Alexander died in 1937 and was buried there too. On the grave they also commemorated Jack's death.

The inscription reads:

Note that the date of Jack's death, and his age, are incorrectly recorded on the gravestone.

Sources

Naval service record (in the name of Arthur Alexander) is available for download from the National Archives (fee payable), reference ADM/473/293263.

Naval service record for Alfred Alexander is similarly available, reference ADM 188/304/182181.

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Alexander |

| Forenames: | Arthur |

| Alternative Forenames: | Jack |

| Rank: | Stoker 1st Class RN |

| Service Number: | 293263 |

| Military Unit: | HMS Majestic |

| Date of Death: | 27 May 1915 |

| Age at Death: | 34 |

| Cause of Death: | Killed in action |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Dardanelles Campaign, Cape Helles |

| Place of Death: | Dardanelles |

| Place of Burial: | Plymouth Naval Memorial |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | No |

| On a Private Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Private Memorial: | Family Gravestone, Longcross Cemetery |

| On Another Memorial? | No |