The Battle of the Falkland Islands

On 1st November 2014, the centenary of the Battle of Coronel, we published on this website the stories of the men of Dartmouth who died in the battle on HMS Monmouth, and a general article describing the series of events which led to the Battle. This follow-up article describes the action taken by the Royal Navy to avenge the defeat, which was, in a very real sense, the second half of the same story. It is published on the centenary of the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

The Admiralty acts

In the words of the official naval history of the war, the Battle of Coronel had inflicted "a serious blow to our naval prestige, at a moment when, as it happened, prestige was peculiarly important, and in addition to the morale effect, it had exposed our command of the Atlantic to real menace ... every vulnerable point all over the world lay exposed to a telling blow from Admiral von Spee ... the whole problem created by the existence of his squadron had not been successfully managed, and nothing but the widest grasp, a bold realisation and acceptance of risks, and the utmost promptitude of action could avail to restore our command".

Only a few days before the Battle, the top of the Admiralty had been in crisis due to the resignation of Prince Louis of Battenberg (Lord Mountbatten's father) as First Sea Lord. After much to-ing and fro-ing between Churchill, Asquith and the King, Lord John Arbuthnot "Jacky" Fisher was brought back out of retirement as First Sea Lord, taking over on 29th October. When the Admiralty received news (on 3rd November) of the appearance of the German squadron off Valparaiso, Fisher immediately ordered HMS Defence to join Admiral Cradock, to strengthen the force at his disposal. But it was already too late. The news of the disaster at Coronel reached the Admiralty the following day, and Fisher took further action immediately.

His first order was to concentrate the available force in the region. Admiral Stoddart, in command of the Canary-Cape Verde station, was ordered to bring together HMS Carnarvon, HMS Cornwall and HMS Defence at Montevideo. The surviving ships of Cradock's force at Coronel - HMS Glasgow and the armoured merchant liner Otranto - were ordered to join him there, together with HMS Canopus, Macedonia (another armoured liner, which Cradock had ordered to escort the Carmania to Gibraltar for repair), and HMS Bristol, which Cradock had ordered to patrol off Brazil. HMS Kent, which had been on the Canary-Cape Verde station, was also ordered to join.

But Fisher was worried that this force was not enough. The shock of defeat had been huge and he would not allow the Navy to take any more chances. He ordered Invincible and Inflexible, two first generation dreadnoughts, to leave the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow, and head to the South Atlantic. These ships combined both high speed and big guns, and, so to speak, trumped Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, the major ships in the German East Asia Squadron, which had inflicted such damage at Coronel. Nor was there to be a moment's delay. On November 5th they left Cromarty Firth and three days later were coaling and resupplying in Plymouth. Invincible needed repairs to her boiler, but she was not allowed to linger - she sailed on 11th November with several dozen workmen still aboard.

On board was Vice Admiral Sir Frederick Doveton Sturdee, who had previously been Chief of Staff at the Admiralty. Fisher disliked him, and also considered him partly responsible for the defeat at Coronel, due to confusing orders and the failure to ensure Cradock had sufficient force available to him. On arriving in his new role, Fisher wanted to fire Sturdee. But Churchill, who recognised that he himself bore some responsibility for what had happened, suggested a compromise. Instead of the ignominy of dismissal, Sturdee was put in the firing line. He was appointed by Churchill and Fisher as Commander in Chief South Atlantic and Pacific, with orders "to search for the German armoured cruisers ... and bring them to action. All other considerations are to be subordinate to this end". He had an unprecented command, a "wider extent of sea than had ever been committed to a single admiral". With this authority he was to proceed as quickly as possible to South America, take Admiral Stoddart under his command, proceed to the key position at the Falkland Islands, and then seek out and destroy Von Spee.

In addition, the available allied naval forces in the Pacific were put on alert. Should Von Spee attempt to go north, he would be met by stiff opposition under command of Admiral Patey of the Australian Navy, and supported by five Japanese ships (Japan having come into the war on the allied side). Finally, dispositions were also made against the possibility that Von Spee might traverse the Panama Canal, and emerge in the North Atlantic.

The Falkland Islands prepare

On the other side of the globe, Glasgow and Canopus met on 6th November at the eastern end of the Magellan Straits, and, needing to re-coal, together headed for the Falklands. They anchored at Port Stanley two days later. The islands' population at that time was not dissimilar to today: 2,772 in the 1911 Census. According to the Oxford Survey of the British Empire, published in 1914: "The main industry of the Falkland Islands is sheep ... bred mainly for wool, but during the last three years two canning factories have begun work ...The advent of whale-hunting ...has not only increased the commercial importance of the Falkland Islands but has made its island dependencies a valuable commercial asset".

The islands' military significance was as the only protected harbour and coaling station available to the Navy in the South Atlantic. A wireless telegraph station communicating with Buenos Aires or Montevideo had been installed in 1911, though it depended on weather conditions to work.

After the defeat at Coronel the islanders felt very vulnerable to attack from Von Spee. Their sole defence consisted in a local force of 160 volunteers, raised by the Governor, Sir William Allardyce. Allardyce discussed his worries with the two captains, and before she left, Glasgow sent ashore a small field gun with ammunition. Having recoaled, the two ships set course for the River Plate, Canopus rather more slowly than Glasgow due to her engines (now nursed by the engineering Lieutenant Commander as the Chief Engineer had suffered a nervous breakdown).

Allardyce's concerns were shared by Fisher. Two days out, Captain Grant of Canopus was ordered to turn back to Port Stanley to remain in Stanley Harbour and thereby provide the islands with some more substantial defence capability. He was to moor the ship so that the harbour entrance was commanded by her guns, and he was told that there was no objection to grounding the ship to obtain a good berth. Over the next two or so weeks, in expectation of Von Spee's imminent arrival, defence was put in place. In Captain Grant's own account:

The Canopus was moored head and stern in Stanley Harbour, and having been beached just before high water and her double-bottom compartments being filled, she was immovable and made a solid gun platform ...From this position we commanded the entrance with two of the 12-inch guns and four of the 6-inch, and covered in the opposite direction a large arc to seaward over the intervening land. The position chosen for the ship rendered her as inconspicuous as possible from seaward, and our topmasts and aerials were struck...

... an observation hut [was] built ... to give the best all-round view to seaward. The ranges and bearings were plotted out for the guns from the position of the ship in relation to the hut by [two lieutenants]. The observation hut was placed in telephonic communication with the ship ...

... mines were laid ... leaving only a narrow passage for vessels entering piloted by an observation boat ... the firing point and observation hut were protected by a 12-pounder and machine gun...

The Local Volunteer force ... was strengthened by 80 of our Marines who were kept ready to land at a moment's notice ... Shore batteries were placed [commanding the harbour entrance, to defend the wireless telegraph station, and at possible landing points.] Look-out stations were manned [by the ship's crew and Volunteers]...

One of the ship's steam boats armed with torpedoes and gun patrolled off the entrance of the harbour at night [with a second boat kept in readiness]...

Telephone communication was erected between all batteries, lighthourse, town, observation station, and the ship. The wireless telegraph shore station was also connected.

The hospital was made ready with extra beds and the old navy yard put in order to accommodate stores.

Captain Grant, his men, and the men and women of the Falkland Islands, then settled down to wait. As events turned out, these preparations made a vital contribution to what happened.

Von Spee reflects

After Coronel, Von Spee left Valparaiso on 4th November and returned to the island of Mas Afuera in the Pacific. His squadron remained there for nine days. Notwithstanding the victory at Coronel, his overall strategic position had not significantly changed. The need for coal ruled out the option of raids on merchant shipping in the Pacific and in the Atlantic. Furthermore, at a tactical level, although his ships had suffered little damage, their armament magazines were severely depleted. He would attempt to make it home to Germany, and keep the squadron together so as to concentrate his force.

On 15th November, they left Mas Afuera, heading south, and by 21st November were in Bahia san Quentin, in the Gulf of Penas on the coast of Chile. Here, on the orders of the Kaiser, Von Spee, who had himself been awarded the Iron Cross First Class and the Iron Cross Second Class, held a ceremony to award 300 of his officers and men the Iron Cross Second Class. He also considered the information that had been coming in about the deployment of the Royal Navy. He knew that Monmouth and Good Hope had been destroyed but that Glasgow had escaped. He had been told that Defence, Cornwall and Carnarvon were in the River Plate. He had also been told that there were no British warships in the Falkland Islands - his source was a ship that had left Port Stanley before Canopus arrived. He did not know, because somehow news never reached him, that Sturdee's ships were coming south. He therefore believed - wrongly - that the Falklands were undefended, and that there were no enemy ships anywhere between Tierra del Fuego and the River Plate.

On 26th November, the German squadron left the Gulf of Penas. But due to heavy weather, they made slow progress. On 1st December, they rounded Cape Horn, and on 3rd December, they anchored off Picton Island. Once again Von Spee paused. The ships coaled from a captured English collier, and the crew shot ducks and brought back branches with red berries to decorate their cabins for Christmas. Von Spee visited Gneisenau to see his son Heinrich, and to play bridge with his friend, Captain Maerker.

On 6th December, however, Von Spee held a conference with his captains. He proposed to attack the Falklands: to destroy the wireless station, to burn coal stocks, and to capture the British governor. Gneisenau and Nurnberg would carry out the attack - the remaining ships of the squadron would wait over the horizon. Two of his captains disagreed with the plan, wanting to head straight home. But Von Spee overruled them, and that afternoon, his squadron headed for the Falkland Islands. On Tuesday 8th December, at 5.30am, on a rare cloudless day, the islands were in sight. Gneisenau and Nurnberg left the squadron to reconnoitre Port Stanley; Scharnhorst, Dresden and Leipzig remained to the south; while three colliers, also with the squadron, waited off Port Pleasant, a bay twenty miles south-west of Port Stanley.

Sturdee heads south

Sturdee and his cruisers left Devonport on the afternoon of 11th November and six days and 2500 miles later reached St Vincent in the Cape Verde Islands, where they stopped for coal. The following day they left.

On 26th November (the same day as Von Spee left the Gulf of Penas), and after a journey of 2300 miles, they reached the Abrolhos Rocks and met up with Admiral Stoddart, who had arrived there the day Sturdee arrived at St Vincent. Now that Sturdee and Stoddart's forces were combined, HMS Defence could be reallocated to other tasks, and she was sent to reinforce the Cape station in South Africa, where additional forces were required in the campaign against German South West Africa.

On 27th November, Sturdee held a conference of captains. News had reached the Admiralty that Von Spee was taking in coal somewhere along the west coast, but nothing further was yet known of his movements. This was sufficient to reassure Sturdee that Von Spee could not reach the River Plate area before him and he proposed to leave Abrolhos for the Falklands on 29th November. But Captain Luce of the Glasgow was very aware of the vulnerability of the Falklands and the fears of the islanders, and as he had been at Coronel, the urgency of arriving first at the Falklands was obvious. He persuaded Sturdee to leave a day earlier. If he had not done so, and if Sturdee had not agreed, Von Spee would have arrived at the Falklands first.

The British force arrived at the Falkland Islands on the morning of Monday 7th December. Von Spee's whereabouts were still not known. Sturdee proposed to remain only for forty-eight hours, before leaving to go round the Horn to find and intercept Von Spee. Sturdee had arrived just in time, but the ships were in no condition for action. They all needed coal and Bristol and Cornwall needed engine repairs.

The Battle begins

Just after 7.30am on the morning of Tuesday 8th December, assisted by the fine weather, a Volunteer lookout on the signal station on Sapper Hill saw smoke on the horizon to the southwest. He telephoned Canopus, on the mudbank in the inner harbour. Canopus could not see Sturdee's flagship, Invincible, in the outer harbour, but was able to signal Glasgow, which was in line of sight of the flagship. Glasgow signalled "Enemy in sight" accordingly. Preoccupied with coaling, the flagship did not notice. Captain Luce fired a gun and trained a searchlight on Invincible's bridge to pass the message. The official history comments that "The surprise was complete".

Only Carnarvon and Glasgow had completed coaling. Kent, Cornwall, Bristol and Macedonia had to make do with what they had. Bristol had closed down her fires to clean her boilers and had opened up both engines for repairs, while Cornwall had one engine in repair. Many officers were still in pyjamas, making plans for the short leave they had been allowed - Sturdee himself was shaving when the news arrived. The only ship at that moment ready to fight was Kent, on harbour patrol. Had von Spee mounted an attack immediately, notwithstanding all the preparations that had been made, the story might have been very different. But he did not even know the ships were there - and in any case, that was not his plan.

At 8.10am Kent was ordered out of the harbour to protect Macedonia, which was on guard duty, and keep the enemy under observation. Macedonia was recalled at 9.15am. All ships were ordered to raise steam. Carnarvon was ordered to clear for action to engage the enemy, and colliers were cast off so that all ships would be free to fire.

Meanwhile Gneisenau and Leipzig came on, in the direction of the wireless station. At 9.20am Canopus fired, training the guns with guidance from the shore observation post. The shots fell short, but had the desired effect. Von Spee had planned to attack an undefended harbour, but it was obvious that there were warships there. He ordered Gneisenau to suspend operations and rejoin the rest of the squadron, and the ships turned and made away to the south-east. Vital time had been gained to get Sturdee's ships out of harbour.

At 9.45am Glasgow joined Kent outside the harbour to keep a look-out; the rest of the squadron then weighed anchor, apart from Bristol, which took an hour to reassemble her engines, and Macedonia, ordered to remain in harbour. (Subsequently Bristol and Macedonia intercepted and sank two of Von Spee's three colliers - the third escaped, but was interned in Argentina). Visibility was excellent - indeed, many of those present on both sides subsequently recalled the exceptional weather - and the enemy's smoke could be clearly seen. Sturdee gave the signal for "general chase". The sense of anticipation was keen, but Sturdee, who had something of a reputation for phlegmatism, decided there was time for lunch, which was signalled at 11.32am.

At this point it became obvious to Von Spee that he was facing not just British warships, but specifically, battle cruisers. Commander Pochhammer of the Gneisenau wrote later: "this was a very bitter pill for us to swallow. We choked a little ...for it meant a life and death struggle, or rather a fight ending in honourable death".

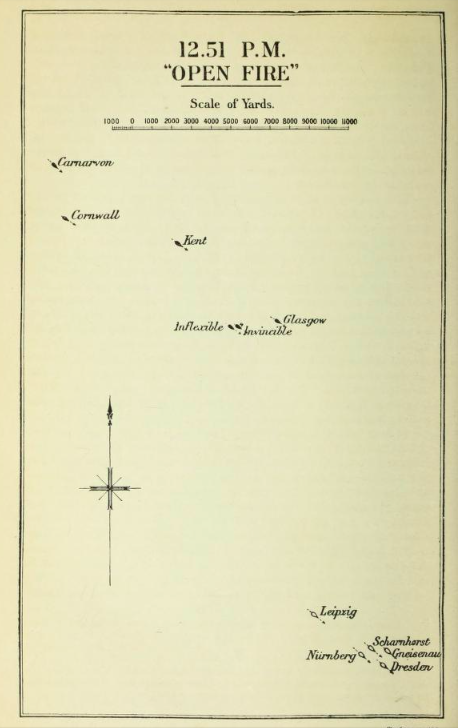

The German squadron was heading southeast. According to the official history, Gneisenau and Dresden were in front, Scharnhorst and Dresden a little behind them, and Leipzig was lagging behind. When the range to Leipzig had closed to 16,000 yards, the Inflexible opened fire at 12.51pm, joined by Invincible a couple of minutes later. This was a very long range, but within fifteen minutes, the range had reduced, and shots were falling very close to Leipzig, with the tall splashes obscuring the ship so that it was thought she had been hit.

Von Spee turns to fight

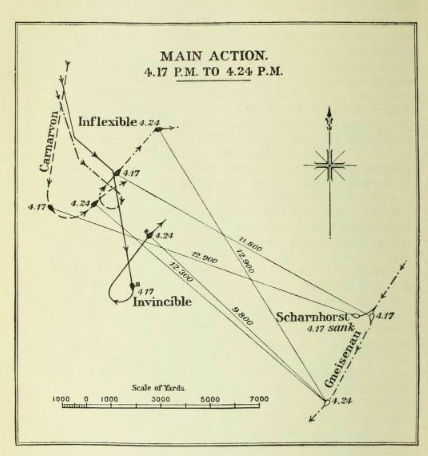

At 1.20pm Von Spee (in the words of the official history) "took a decision which did him and his Service the highest honour". He split his squadron - the light cruisers broke off southward, and Scharnhorst and Gneisenau turned to port, to the north-east, directly into the path of the British battle cruisers.

Sturdee had foreseen this. At the Abrolhos Rocks he had issued three pages of instructions to the effect that, in any action, if the German squadron divided, Invincible and Inflexible would take on Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, while the British armoured cruisers would deal with the German light cruisers. Thus, when Captain Luce in the Glasgow saw the German light cruisers turn away, he immediately headed for them, followed in turn by Kent and Cornwall (Carnarvon was some distance behind the main group due to inability to keep up speed, and remained with the battle cruisers). Invincible and Inflexible engaged Gneisenau and Scharnhorst respectively, Sturdee manouevring to fight at a range beyond that of Von Spee's guns, and Von Spee maneouevring to reduce the range.

During this first phase, German fire had been rapid and effective, when the range permitted. British gunnery had been rather ragged, hampered by the northeast wind blowing smoke from funnels and guns across the gunners' line of vision. But those that did hit had inflicted serious damage. Von Spee suddenly turned and made off south, hoping that his move would not be seen through the smoke. Sturdee gave chase. By 2.45pm the range was down to 15,000 yards and he once again opened fire. Eight minutes later Von Spee turned to accept battle and the manouevring began again.

By 3.00pm the range had diminished. The Invincible was hit repeatedly, but by some quirk of fate, there were almost no casualties. Some shells failed to explode - one 8.2 inch shell went through the muzzle of a forward 4-inch gun, descended two decks, and came to rest without exploding in the admiral's storeroom, between his jams and a Gorgonzola cheese. Another 5.9 inch shell passed through the chaplain's quarters, entered the paymaster's cabin, and passed harmlessly through the ship's side. Meantime the gunners had got their eye in. By 3.10pm the Gneisenau was listing and the starboard engine room was smashed; five minutes later, the Scharnhorst, which was burning in places, had her third funnel shot away.

At 3.16pm, in an effort to clear the smoke, Sturdee led his ships round in an arc to place them to windward of the German cruisers. For a few minutes his gunners had a clear target, until von Spee turned himself. Scharnhorst, in the words of an eye witness, was "a shambles of torn and twisted steel and iron, and through the holes in her side, even at the great distance we were from her, could be seen dull red glows as the flames gradually gained the mastery between decks". But she kept firing. Although the port guns were disabled, the turn brought the starboard guns to bear. By this stage, both Invincible and Inflexible were firing at her, securing hit after hit, but she maintained her return fire until just before four o'clock, when she stopped. Sturdee signalled her to surrender, but there was no reply. At this point Spee sent his last signal to Gneisenau ordering her to save herself, and at 4.17pm, flag still flying, she sank, with no survivors from her 800 officers and crew, including Von Spee himself.

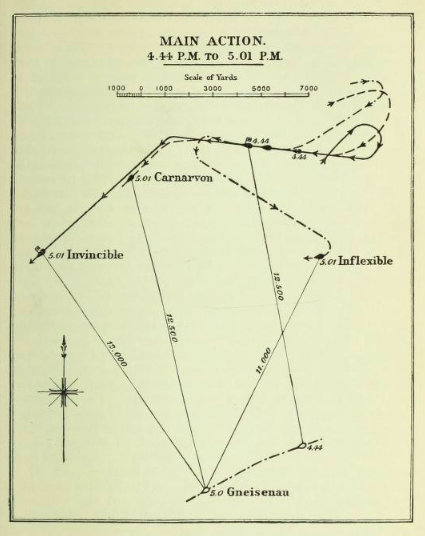

Gneisenau faced surrender or complete annihilation. Captain Maerker chose the latter. She faced overwhelming fire from Invincible, Inflexible, and Carnarvon, which had finally reached the battle. But she kept firing back. Several times her colours were shot away, and several times they were hoisted again. Finally the end came. At 5.40pm Captain Maerker gave orders to scuttle the ship. She submerged slowly, allowing those of her crew, still alive at that time, to leave the ship, finally sinking at 6.00pm.

The British ships launched a rescue attempt for survivors, though many of their boats had been damaged in the fight. Many men drowned before they could be reached. Invincible picked up 108 survivors, Inflexible 62, and Carnarvon 20. Heinrich von Spee, the admiral's son, was not amongst them.

In the end, the fight had been unequal - amongst the British ships' companies, only one man had been killed. The Invincible had received most of the enemy fire. She had been hit about twenty times, and though "much knocked about" had suffered no significant injury other than losing a strut of her foremast. Two of her crew had been slightly wounded. The Inflexible had "only a few scratches", from three hits. Casualties were one man killed and four wounded. The Carnarvon (which had come late to the fight) was not touched.

Leipzig, Dresden and Nurnberg turn to fight

In the meantime, Glasgow, Kent and Cornwall had chased after Leipzig, Dresden and Nurnberg. In armament the British ships were superior, but in design speed, apart from Glasgow, the margin was narrower. However, the German ships had been at sea for four months and had had no opportunity to clean their hulls, boilers and condensers, so their speed in practice was less.

By 2.45pm Glasgow had been able to catch up with Leipzig and engaged her. Leipzig turned and fired and scored two hits. Captain Luce pulled back out of range, and the chase resumed. This happened twice; but each time Leipzig turned back to fire, she lost ground, enabling Kent and Cornwall to catch up.

At 3.45pm the German force divided. Dresden, which was in the lead, turned southwest, Nurnberg turned east, and Leipzig continued south. Captain Luce decided to let Dresden go - she had a start on him of sixteen miles, the weather was worsening, and he would be unlikely to catch up with her for at least a couple of hours. He decided to continue to target Leipzig, along with Cornwall; Kent in the meantime went after Nurnberg.

Cornwall and Glasgow together engaged Leipzig for nearly an hour. Leipzig was hit time after time, but she continued to fire back. Cornwall then began to fire special high-explosive shells, with terrible effect, but still Leipzig continued to return fire. By 7.05pm, she was a wreck, but her flag was still flying. Her captain had ordered her to be scuttled, and her remaining crew had gathered on deck, but fires prevented them hauling down her flag (one man tried to do so and was burned before he could reach the mast). Glasgow and Cornwall waited for the flag to come down, but when it did not, resumed fire, with terrible loss of life amongst the men on deck. At 8.12pm, Leipzig fired two green distress lights and the British took this as surrender. Glasgow and Cornwall put boats into the water for rescue. Leipzig's captain, who was still alive, ordered the remaining crew into the water, but himself walked into the sea and disappeared. As the rescue boats approached, Leipzig sank, at 9.23pm.

Cornwall had been hit eighteen times but had lost no-one. Glasgow had been hit twice, with one man killed and four wounded. Both set course for Port Stanley having heard already about the outcome of the fight with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and Glasgow having in any case run out of armament.

Kent meantime had achieved miracles in pursuit of Nurnberg. Though older and only recently recommissioned, and though she had experienced severe problems with her engines, on her way to the Falkland Islands, she somehow caught up with Nurnberg. The ship's crew had made up for the shortage of coal by feeding into her furnaces all the wood they could find aboard the ship - ladders, doors, furniture, even deck timbers. The Nurnberg meanwhile had burst two boilers, so her speed had dropped. When the two ships engaged at 5.45pm, the distance between them was short. Kent had heavier guns and was armoured. Most of Nurnberg's shells failed to penetrate, though one hit a gun position, and another wrecked the wireless room. Nurnberg, on the other hand, by 6.25pm was a wreck. At just before 7.00pm she hauled down her colours and at 7.27pm she sank.

Only two of Kent's boats were able to float. The search for survivors was continued until 9.00pm but the sea was very cold and was growing rougher. Only twelve of Nurnberg's crew of 400 were picked up alive and five later died. Von Spee's other son Otto was among those lost.

Kent had been hit thirty-seven times but her armour had not been pierced. Her casualties were five killed and eleven wounded, of whom three died later. Due to the destruction of the wireless room she was unable to transmit her position so the rest of the British squadron did not know what had happened to her. Due to lack of coal she could make only slow progress and she returned to Port Stanley the following day.

Sturdee, not having heard from Kent, had made for her last known position but found nothing. He had sent Carnarvon to escort eight colliers being brought down to the Falklands. In the meantime he attempted to pursue the Dresden, but was hampered by thick fog and was running short of coal. He abandoned the hunt and returned to the Falklands.

On 13th December, Sturdee was told by the Admiralty that Dresden had arrived the previous day in Punta Arenas. Bristol was sent immediately to Punta Arenas, with Inflexible and Glasgow following, but the bird had flown. Invincible had been holed on the waterline, damage which the crew could not repair. She departed for dry dock in Gibraltar and Sturdee departed with her, leaving the search for Dresden to Admiral Stoddart.

Dresden is found

On 19th December Inflexible was withdrawn from the search, ordered home to England. Kent and Glasgow continued to hunt. Eventually, on 8th March 1915, they found her, but once again she escaped. This time, however, a message from her to a collier to meet at Mas a Tierra in the Juan Fernandez islands was intercepted. Kent and Glasgow found her six days later. As Glasgow approached, Dresden trained her guns, and Captain Luce opened fire. Four minutes later, Dresden, on fire, and holed at the waterline, hoisted a white flag. She tried to parley, asserting that she was under Chilean protection. Luce replied that unless she surrendered he would fire. While this was going on, her captain had been making preparations to scuttle her, and when the parley boat returned, her company left the ship to make for the shore. Dresden sank twenty minutes later. Of the five German captains who reached the Falklands with Admiral von Spee, Dresden's captain, Ludecke, was the only one to survive the battle and the war.

During the search for Dresden, the British had also continued to search for Karlsruhe. The Karlsruhe had arrived in the West Indies to replace the Dresden just before the war began and both ships had remained in the Atlantic. Dresden had gone south to meet Von Spee but Karlsruhe had continued to carry out raids on merchant shipping off the coast of Brazil. Nothing had been heard of her in recent months but what had happened to her was unknown.

In March 1915 some of her wreckage was found. She had suffered an internal explosion and sunk with the loss of 261 officers and men, three days after the Battle of Coronel.

Postscript

So ends the story of Coronel and the Falklands. The threat posed by German overseas warships around the world at the outbreak of war had been eliminated, and the Navy's reputation was restored. Fisher was delighted with the success of the battle cruisers, although he considered that the primary architect of the victory was himself, and that Sturdee was merely lucky that Von Spee so obligingly came to meet him. Indeed, Fisher rather resented the public acclaim which was heaped upon Sturdee, whom he continued to dislike and whom he described in 1919 as having been "kicked on to a pedestal".

Was Sturdee just lucky? In 1933, a certain Franz von Rintelen, a German Naval intelligence officer, alleged in his memoirs that in 1925 he was told by Admiral Sir Reginald Hall, the Director of Naval Intelligence during the war, that a British agent in Berlin had used forged or stolen telegram forms to send orders to Von Spee at Valparaiso, just after Coronel, to "proceed to the Falkland Islands with all speed and destroy the wireless station at Port Stanley". In this version of events, Von Spee's decision to attack the Falklands was thus not his initiative, but a British plot to ensure that the squadron sent out to destroy him would be sure to locate him, for which he fell.

The story is intriguing. But if it was true, it seems odd that Von Spee told the German Admiralty on 16th November that his intention was to head home - if he previously had received what he considered were genuine orders to go to the Falklands. Rather, his decision seems to have been opportunistic, formulated in light of what he thought he knew about naval dispositions - similar to his attempted attack on Samoa three months earlier. Perhaps von Rintelen - a German naval officer - simply found it impossible to acccept that the extent of Sturdee's good luck, or Von Spee's bad luck, in encountering each other when they did (if Von Spee had arrived even a day earlier, or Sturdee a day later etc) was no more than fortunate coincidence. Or perhaps Sir Reginald Hall just enjoyed a joke at Von Rintelen's expense.

The official history comments: "It may be said that the fortunate meeting at the Falklands was mainly a point of luck, but it was luck fairly won on Nelson's golden rule of never losing a wind ... What the action meant to the course of the war was that in little more than four months the command of the outer seas had been won, and we were free to throw practically the whole weight of the Navy into the main theatre".

Had Admiral Cradock been given adequate forces and clear orders in the first place, however, that supremacy might have been achieved at rather less cost, in Dartmouth and elsewhere.

Sources

The principal sources on which the above account is based are:

History of the Great War, Naval Operations Vol 1, Sir Julian S Corbett, publ Longmans 1920, available online (also on naval-history.net)

Diagrams used above come from the official history.

Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea, Robert K Massie, Vintage, 2007

Casualty numbers were taken from naval-history.net

The Oxford Survey of the British Empire, Vol 4, America (including also the Falkland Islands, Clarendon Press, 1914, available online

My War At Sea, 1914-1916, Heathcoat S Grant, published online by WarLetters.net, 2014

The Dark Invader: War-Time Reminiscences of a German Naval Intelligence officer, Captain von Rintelen, pub Penguin, 1933, available online.