The Battle of Coronel

The British Empire was a global concern and at the outbreak of war the strategic issues were global in scope. The series of events which led to eight Dartmouth men (and 727 others) dying in HMS Monmouth on the far side of the world on 1st November 1914 began several months earlier and spread across both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

The North and South Atlantic

A preoccupation of Admiralty war planners was the fear of a food panic in the first weeks of the war. Effective commerce protection in both the North and South Atlantic was consequently a high priority - partly to prevent actual capture of merchant shipping, but just as much to maintain morale at home. Trade with the United States and Canada was of huge significance, but almost equalling it was trade with South America - meat and grain from Argentina, nitrates from Chile, and coffee from Brazil.

Before the war, the only German warship in the western Atlantic was the Dresden, a fast, light cruiser. It so happened that she was due to be replaced in July by the Karlsruhe, a still more modern light cruiser. The Karlsruhe arrived in the West Indies on 25th July and war broke out before the Dresden went home. Both ships therefore remained in the western Atlantic, with orders to attack British trade. Furthermore, American ports, especially New York, were full of fast German civilian liners, capable of being converted into armed merchant cruisers, formidable destroyers of commerce.

Responsible for meeting this threat were Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, who was the Commander in Chief of the North American and West Indies station, and Rear Admiral Archibald Peile Stoddart, who was assigned to the Mid-Atlantic, between the West Coast of Africa and Brazil. Cradock had been allocated initially four old County-class cruisers: Suffolk, Berwick, Essex and Lancaster, as well as the more modern light cruiser, Bristol. Stoddart was assigned four more County-class cruisers: Carnarvon, Cornwall, Cumberland and Monmouth.

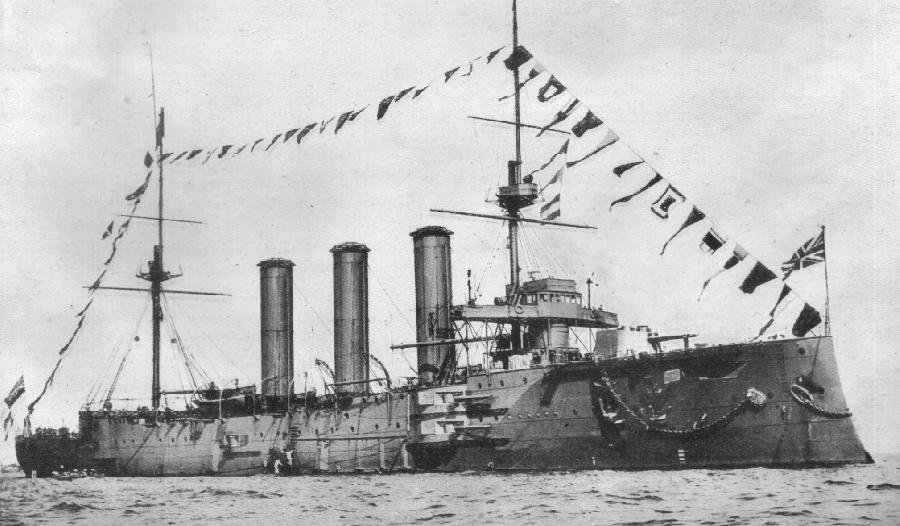

HMS Monmouth had earlier served on the China station before going into reserve in January 1914. She had been due a long refit but was hurriedly recommissioned on mobilisation. She was old, having been laid down in 1899 and launched in November 1901. Like her sisters in the County class, she was relatively fast (designed for 23 knots) but being designed to fight only light cruisers and armed merchant ships, was armed with fourteen 6-inch guns. Four were mounted in two twin turrets at a good height, but the remaining ten were installed along the side of the ship in hull-mounted casemates. The lower casemates, with six guns in all, were just a few feet above water, making them impossible to use in heavy seas - if the doors were kept open the waves came in.

It is often said of HMS Monmouth that she was crewed with reservists, coast guardsmen, boy seamen, and naval cadets. However, the sailors from Dartmouth who joined her on 30th and 31st July were all Naval regulars. Although three of them were new to the Navy, the average prior Naval service across the group was 5.6 years, and the average age was 24. The most experienced, William John Henry Blank, had been in the Navy for 18 years and had served on HMS Monmouth before.

It is true that on board were many of the cadets who had been mobilised from Dartmouth at the start of the war. In addition to ten who had previously been allocated to Monmouth, she was also carrying a further twelve who had been due to join HMS Carnarvon, but had not been able to get to Devonport by the time she sailed to join Admiral Stoddart. Monmouth arrived at St Vincent in the Cape Verde islands on 13th August, where she caught up with the rest of Stoddart's squadron, and the cadets were transferred. She had been delayed leaving the dockyard in Portsmouth and nearly did not make the rendezvous. If she had not, all would most likely have died, along with their contemporaries who remained on board. One of those transferred to Carnarvon, Raymond Mandley, kept a diary in which he wrote: "As we stepped aboard [the ship] I heard a marine say "Here's some poor little chaps being sent to be killed". If I had known that we were the only ones that were to be saved from that ill-fated ship ...". Another, Patrick Blackett, who subsequently became a Nobel prizewinner, was as a result of this event profoundly impressed with a sense of his own destiny, according to his family. For further background on Dartmouth cadets and HMS Monmouth, please refer to our article "The Unjust Load".

In addition to Cradock in the West Indies and Stoddart in the Cape Verde Islands, there was also the light cruiser HMS Glasgow, which had for the last two years been single-handedly looking after British interests along the east coast of South America. In July 1914, Glasgow was in Rio de Janeiro looking forward to returning home to England (many of the crew having bought parrots to bring home with them). When the ship was stripped for war, and all extraneous personal possessions sent ashore, the captain, John Luce, agreed exceptionally that the parrots could stay.

During the two years of his service in South America, Luce had been concerned about coal supplies in time of war. The problem was not buying coal so much as finding a safe harbour in which to transfer it. Luce had found two places that could serve in an emergency (other than the Falklands) - the Abrolhos Rocks, uninhabited islands (except for a lighthouse) surrounded by reefs fifteen miles off the Brazilian coast, and the estuary of the River Plate, seven miles off the coast of Uruguay.

As the war began, Cradock's initial focus was on the North American trade routes, where there were rumours that German merchant cruisers were operating. The Good Hope, an old battleship (launched 1901) from the reserve fleet, which was originally due to go to the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow on the declaration of war, was instead diverted to Halifax, Newfoundland, to provide temporary reinforcement for the North Atlantic trade routes.

However, despite the Admiralty's fears, no German liner had put to sea since the declaration of war, and in the meantime firm news had arrived that Dresden and Karlsruhe were operating well to the south, Karlsruhe at Curacao and Dresden off the Amazon. Cradock was therefore tasked to reinforce the southern section of his command and to do so, he requested the Good Hope be added permanently to his squadron. The Admiralty agreed and Cradock made her his flagship. He decided to go south himself in search of the German ships. Leaving Suffolk, Lancaster and Essex to look after the northern section of his command, he went south to join the Berwick and the Bristol in the West Indies.

In parallel, Stoddart in Cape Verde was told to provide support by making his fastest ship available to Glasgow. On Monmouth's arrival at St Vincent Island (and having transferred the cadets to Carnarvon), she was sent south across the Atlantic to rendezvous with Glasgow off the Pernambuco area of north-eastern Brazil, with orders to support Glasgow in the search for Dresden. When she arrived, on 20th August, at least one officer on Glasgow was not impressed by what she had to offer. Lloyd Hirst, Paymaster Commander and Intelligence Officer, wrote in his diary:

"Sighted Monmouth at 11am. She had been practically condemned as unfit for further service, but was hauled off the dockyard wall [and] commissioned with a scratch crew of coast guardsmen and boys. There are also twelve1 little naval cadets as keen as mustard. She left England on August 42, she is only half equipped and is not in a condition to come six thousand miles from any dockyard as she is kept going only by superhuman efforts".

By this time the threat from Dresden was assuming increasing proportions. The same day that Monmouth met Glasgow, the Admiralty received news that Dresden had sunk the Houston liner Hyades four days earlier (having taken off the crew and sent them into Rio). She had also met and stopped other merchant ships, but had not sunk them. The Admiralty's assumption was that her mission was to destroy as much South American trade as possible. In fact, she had orders to go to the Pacific (see below) and such encounters as she had with merchant ships were opportunistic.

Glasgow and Monmouth went off towards Cape San Roque, north of Pernambuco, to search for Dresden. On 28th August, they were joined by the Otranto, an armed merchant line which had originally been built for the UK-Australia run. Finding nothing, the three ships went south to the Abrolhos rocks to recoal, heading for the River Plate.

Meanwhile Cradock had begun a search along Brazil's north coast. The threat from the Dresden had shaken confidence amongst British traders in South America, and in response, the Admiralty ordered Cradock to remain permanently in command on the South American station. He was to be reinforced by a battleship, the Canopus, which had previously been acting as guardship at St Vincent, Cape Verde islands, for Admiral Stoddart. He was also sent the armed liner, Macedonia. (His command in the West Indies was to be taken over by Admiral Phipps Hornby, to whom the Berwick was to return).

On 29th August, a report reached him that an armed German liner, the Cap Trafalgar, was at the St Paul Rocks, midway between the African and Brazilian coast, and this suggested that the Dresden might be there also. He went to search, but found nothing. At about the same time, Admiral Stoddart also sent one of his squadron, the Cornwall, in search of the Cap Trafalgar. The Cornwall then remained with Cradock; and at the end of August, he was additionally joined by a British armed liner, the Carmania, which, having brought out supplies to him, stayed with him.

(It was the Carmania which despatched the Cap Trafalgar. On 14th September, they encountered each other at Trinidad Island, which was suspected of being used as a secret coaling base by the Germans. Trinidad Island (not to be confused with Trinidad in the West Indies) lies about 600 miles east of South America, on the same latitude as Rio. On being discovered coaling there, Cap Trafalgar at first ran for it, but then turned to fight. What followed was the first ever battle between ocean liners. After a short time, both ships were on fire - but Carmania prevailed and eventually Cap Trafalgar sank. Carmania was badly damaged, however, and had to be escorted back to Gibraltar by the Macedonia, to make repairs. Five men had been killed, four died of wounds, and twenty-two were injured.)

On the same day, Cradock met Glasgow, Monmouth and Otranto at Santa Catharina, about 250 miles south of Rio, where they had headed following yet another false report of Dresden's whereabouts. Cradock's assets at this stage were therefore:

- Good Hope

- Glasgow

- Monmouth

- Otranto

- Bristol

- Cornwall

- Canopus, on the way.

At this point, however, his situation changed, due to events in the Pacific.

The Pacific

At the outbreak of war, based at Tsingtao on the north China coast, in a territory leased to Germany by China for 99 years in 1899, was the East Asia squadron of the Imperial Navy, Germany's second most powerful force afloat. The squadron's role was to police Germany's imperial possessions in the Pacific - the Marianas, the Carolines, the Marshall Islands, and Samoa in the central Pacific, and the Solomon Islands, German New Guinea, Neu Pommern, and Neu Mecklenberg to the south.

The two most important ships in the squadron were the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, formidable modern ships, well armed and protected. They were manned by long-service crews and under Vice Admiral Count Maximilien von Spee, the squadron's commanding officer, they had practised their gunnery until they had become the best in the German Navy. Supporting them were three modern light cruisers, Emden, Leipzig, and Nurnberg.

In June 1914, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau left on a three month cruise around the Pacific. As the international situation worsened, Admiral von Spee realised he would need to modify his plans. On August 1st he was at Ponape in the East Caroline Islands, and the Nurnberg joined him there from Honolulu on 6th August. A supply fleet, led by Emden, had left Tsingtao the day before. Von Spee ordered a rendezvous with the supply fleet back at Pagan Island, which they had visited a few weeks earlier. (Leipzig in the meantime was operating off the North American coast and so did not join the squadron until much later - see below).

Although the East Asia Squadron was a powerful force, Von Spee was in a difficult position. He had two tactical alternatives - break up the squadron and let individual ships, or pairs of ships, wage war on trade; or keep the squadron together to concentrate his force against enemy navies. Trade warfare suited his light cruisers, but not the armoured cruisers, which were not as fast. Furthermore, individual ships would sooner or later be hunted down; together, the squadron had a better chance of survival, and might even achieve something.

Westwards, he faced the British China Squadron, under Admiral Jerram, and the British East Indies Squadron, under Admiral Peirse. Though he might have been able to defeat either of these on their own, the risk was very substantial were they to combine. Furthermore, if Britain's ally Japan came into the war (which it did on 23rd August) he would have to face the powerful Japanese fleet too, with three dreadnoughts and fifteen other battleships. South, he faced the Australian Navy, including the dreadnought battle cruiser Australia. (Indeed, both Admiral Jerram and Admiral Patey, of Australia, were much preoccupied with what Von Spee would do, but for several weeks neither was in a position to pursue him, having other priorities to meet. By the time they were free of other commitments, von Spee was thousands of miles away).

Eastwards, however, he faced no opponents; he could readily conceal his intentions, lost in the vast Pacific seas; and above all, once he reached South America, there were many nations that would sell him coal, particularly in Chile, where there was a large German population. The squadron needed a coaling stop every eight or nine days and to supply all the ships with coal from prizes would be impossible - the quantities he needed would have to be bought. From South America, there would also be opportunities for communication with home. Finally, there was the possibility of rounding Cape Horn and passing into the Atlantic, and from there, doing damage to the enemy and maybe even, getting home to Germany.

He therefore decided to take the long road across the Pacific. However, at the request of her captain, Emden would be despatched into the Indian Ocean as a lone raider, to do what damage she could to enemy trade (in which she was very successful - she became the most effective German commerce raider of the Great War, intercepting 29 Allied and neutral merchant ships, and sinking sixteen British merchant ships, a Russian cruiser, and a French destroyer, until her raiding career was brought to an end on 9th November by the Australian light cruiser Sydney, which forced her to surrender).

On 13th August, Von Spee and his squadron sailed. His plan was to reach the Chilean coast on 15th October.

On 19th August, he was at Eniwetok, a coral atoll in the Marshall Islands. He was unable to communicate with Berlin because the German wireless station on Yap in the western Carolines had been destroyed by the British cruiser Minotaur, of the British China Squadron. Von Spee therefore sent Nurnberg to Honolulu, to advise Berlin of his plans and gather information.

On 26th August, he stopped at Majuro, another atoll at the southeastern edge of the Marshall Islands, and took on a delivery of coal and other supplies which had been able to escape from Tsingtao.

On 7th September, the squadron reached Christmas Island, a British possession, but one occupied only intermittently by copra gatherers. Nurnberg rejoined them from Honolulu. She had learned that on 30th August, Apia, the capital of German Samoa, had been occupied by New Zealand troops. Von Spee decided to mount a surprise attack on what he hoped would be naval or supply ships for the garrison. On 14th September, he reached what had been German Samoa. But the harbour was deserted. Attempting to recapture the island would be costly, so he left. As he did so, he heard the Apia wireless station broadcasting his position, so he steamed first to the north-west, only resuming his course when out of sight of land.

The Admiralty Changes its Mind

That very day, the Admiralty, not knowing Von Spee's whereabouts, and increasingly worried, sent Cradock a signal:

"There is a strong probability of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau arriving in the Magellan Straits or on the West Coast of South America. The Germans have begun to carry on trade on the West Coast of South America. Leave sufficient force to deal with Dresden and Karlsruhe. Concentrate a squadron strong enough to meet Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, making Falkland Islands your coaling base. Canopus is now en route to Abrolhos, Defence is joining you from Mediterranean. Until Defence joins, keep at least Canopus and one County class cruiser with your flagship. As soon as you have superior force, search Magellan Straits with squadron, being ready to return and cover the River Plate, or according to information, search north as far as Valparaiso, break up the German trade and destroy the German cruisers ....".

Cradock, on receipt of these rather complicated orders in which he was required to do several things at once, decided to dispose his assets as follows. Bristol was to patrol south of Rio, towards Montevideo, and Cornwall to patrol between Rio and Cape San Roque. Carmania was on her way to Gibraltar to repair and refit following the action with Cap Trafalgar, with Macedonia accompanying. When Macedonia returned she would support Bristol and Cornwall. Cradock himself in Good Hope would go south to the Falkland Islands, taking Glasgow, Monmouth, and Otranto, to search the Magellan Strait and "being ready" to go up either the east or west coast of South America "according to information".

The good news for Cradock was the promise of the modern armoured cruiser Defence, as she was faster and more powerfully armed than Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, Canopus, on the other hand, though she had four 12 inch guns, was old, slow, and unreliable. But whether these six rather unmatched ships would have been enough to "destroy the German cruisers" was not to be tested. Two days later, the Admiralty received news of Von Spee's appearance at Apia, Samoa, and his apparent disappearance to the north-west - the presumption was that he was returning to Tsingtao This caused an about turn in the new plans. On 18th September, Cradock received another signal:

"Situation changed. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau appeared off Samoa on 14th and left steering NW. German trade on west coast of America is to be attacked at once. Cruisers need not be concentrated. Two cruisers and an armed liner appear sufficient for Magellan Straits and west coast. Report what you propose about Canopus".

The Admiralty cancelled Defence's orders to go south and sent her back to the Dardanelles. However, they failed to tell Cradock this and he continued to expect her. He also suspected that Von Spee was still heading for the Straits of Magellan, and, in the meantime, he was still hunting Dresden - the British consul in Punta Arenas told him on 28th September that Dresden had been at Orange Bay on the southern coast of Tierra del Fuego. On 29th September, the British squadron - Good Hope, Glasgow, Monmouth, and Otranto rounded Cape Horn and entered Orange Bay, but Dresden was not there. They made a second visit on 6th October, after coaling at the Falkland Islands, and once again the bay was empty, though they did find evidence that Dresden had been there, nearly a month before.

Good Hope then returned to the Falkland Islands to coal and to stay in touch with London, while Glasgow, Monmouth and Otranto once more went round Cape Horn in huge seas. Writing of this period, an officer in the Glasgow said: "It blew, snowed, rained, hailed and sleeted as hard as it is possible to do these things. I thought the ship would dive under altogether at times ... The Monmouth was rather worse, if anything ...We were rolling 35 degrees, and quite useless for fighting purposes. The ship was practically a submarine".

Otranto was left in the vicinity of the temporary coaling base established at Vallenar roads, amongst the Chilean fjords, while Glasgow and Monmouth went further north. On 14th October they were at Coronel, a small coaling harbour, with white sandy beaches and forests of fir and eucalyptus, some 275 miles from Valparaiso. On 15th October, Glasgow put into Valparaiso. Monmouth stayed outside for gunnery practice while Glasgow put into port to talk to the British Consul.

A letter written on 14th October by Royal Marine Bandsman William Wileman Hart, a member of Monmouth's company, provides a rather happier picture of life on board the ship during this time:

"We are just off Chile now on the other side of America. The weather is perfect now but all last week we had very rough weather round Cape Horn. We were hunting round there for a supposed German warship we searched all amongst the islands and inlets for over a week but could not find any trace of her ... The scenery in the Magellan straits was beautiful the numerous islands and snow capped mountains. We crossed over to the Falkland Islands very cold there our butcher and a few others went ashore and killed fifty two wild sheep so we have been having plenty of mutton. Officers went ashore and killed wild duck and pheasants so we have been living in stile (sic) ... A provision ship is expected to meet us at Valparaso so we shall be all right. I am living well at present. Having porridge, dripping and perhaps corned beef for breakfast, roast meet, beans (Harrogate) and pudding for dinner. Jam for tea and corned beef again for supper ...We anchor on an average once a week in some uninhabited part of the coast and coal from our collier ..."

He continued "There are some German warships round here somewhere but we can't find them they are hiding from us. I expect we shall meet them sooner or later"

On 18th October, they were back at sea. Monmouth was having her own problems - on 21st October she reported boiler defects and announced that she would be out of action by January.

The Pacific - Von Spee continues his voyage

Having successfully deceived the Admiralty into thinking he was proceeding north-west, Von Spee continued his course east. On 21st September he arrived at Bora-Bora, an island of the Tahiti group and a French colony. The authorities thought the visitors were English (Von Spee showed no flag) and he was able successfully to maintain the deception so as to obtain supplies. As he left, he was saluted, and only on leaving raised his own flag in response.

From Bora Bora he continued to Papeete, the port and capital of Tahiti, which he reached on 22nd September. The French had been warned by the authorities on Bora Bora and they had burned all supplies of available coal. Von Spee fired at, and sank, an anchored French gunboat, before leaving for the French Marquesas, which he reached on 26th September. He was able to remain there for a week, coaling and taking on fresh provisions, and left on 2nd October. By this stage, Dresden was off the coast of Chile (where the British had failed to find her). On 4th October, Von Spee signalled Dresden to join him at Easter Island, a Chilean possession, which he reached on 11th October. Also joining him at Easter Island was Leipzig, which (having spent the months of August through to September off the coast of North America) was escorting colliers from San Francisco to meet him. When she arrived, on 14th October, Von Spee's squadron was once again at full strength - two armoured and three light cruisers.

Four days later, they left for the Chilean coast. On 26th October they were at Mas Afuera, an island 450 miles from the Chilean coast, left there on 28th October, and on 30th October were forty miles west of Valparaiso. Von Spee had travelled 12,000 miles, but had achieved little, other than causing the Admiralty a severe headache. This was about to change.

The Admiralty Changes its Mind Again

News of the attack on Papeete had reached the Admiralty by 30th September and Von Spee's signal to Dresden four days later was intercepted by a British wireless station in the Fiji Islands. Finally the Admiralty knew not only where he was, but where he was going, and there was little doubt that the South American coast was his destination.

As he returned from the second abortive trip to Orange Bay, Cradock received a signal on 7th October which alerted him to the new situation:

"... it appears that Scharnhorst and Gneisenau are working across to S America. You must be prepared to meet them in company possibly with Dresden accompanying them. Canopus should accompany Glasgow, Monmouth and Otranto, the ships to search and protect trade in combination. Arrange about coal and consider whether a collier should accompany squadron. If you propose Good Hope to go, leave Monmouth on east coast..."

Cradock replied asking whether Defence was (in effect) still on her way (as no one had told him she was not). He also asked for Essex (in the West Indies) to relieve Cornwall (off Brazil), so that the latter could join him. He was obviously concerned about having sufficient force to meet Von Spee. The Admiralty was at the time much preoccupied with the defence of Antwerp, and had not answered this signal by the time Cradock sent another, on 11th October. This pointed out the risk of attempting to cover both the west and east coast of South America, and meet and defeat Von Spee, with a single squadron:

"Without alarming, respectfully suggest that in event of the enemy's heavy cruisers and others concentrating West Coast of South America, it is necessary to have a British force on each coast strong enough to bring them to action. For otherwise should the concentrated British force sent from SE Coast be evaded in the Pacific, which is not impossible [and] thereby [get] behind the enemy, the latter could destroy Falkland, English Bank and Abrolhos coaling bases in turn, with little to stop them, and with British ships unable to follow up owing to want of coal. Enemy might possibly reach West Indies".

He therefore suggested that a new backup squadron of additional ships should be formed on the east coast: Good Hope, Canopus (still at this stage on the way from Cape Verde), Defence (which he thought was still on the way from the Mediterranean), and Cornwall. He may well have assumed that he would have control of both squadrons, as the man on the spot, and therefore be able to decide how to concentrate and allocate these resources so as to meet and defeat Von Spee.

The Admiralty recognised the risk that von Spee might evade Cradock in the Pacific or in the Magellan Straits, and come round Cape Horn. They agreed to the formation of a second squadron, but not under Cradock. On 15th October, Cradock received their signal:

"Concur in your concentration of Canopus, Good Hope, Glasgow, Monmouth, Otranto for combined operation. We have ordered Stoddart in Carnarvon to Montevideo as Senior Naval Officer north of Montevideo. Have ordered Defence to join Carnarvon. He will also have under his orders Bristol, Cornwall, Orama and Macedonia. Essex is to remain in W. Indies..."

Much significance was attached by the Admiralty, particularly Churchill, to Canopus and her four 12 inch guns. Long after the battle, Churchill continued to hold the view that Cradock would have been safe if he had kept in company with her. However, others had their doubts - for example, Lieutenant Hirst: "[Canopus] was seventeen years old. Her antique 12 inch guns ... had a maximum range of ... three hundred yards less than those of the German heavy cruisers, and they were difficult to load and lay on the heavy seaway prevalent in the South Pacific".

Further, there were problems with her engines which had seriously affected her speed. Canopus reached Port Stanley on 22nd October and her captain, Heathcoat Grant, told Cradock that the best Canopus could achieve was 12 knots, and that further, he could not leave port until various repairs had been done. Cradock felt unable to wait further - Glasgow, Monmouth and Otranto, on the Chilean coast, needed his support. On 22nd October, he left to join them, ordering Canopus to follow. According to Sir William Allardyce, the Governor of the Falkland Islands, who had spent a great deal of time with Cradock during his stay in Port Stanley, he knew he was going to almost certain death: "Cradock thought his chances were small and that he had been let down by the Admiralty, especially when his request for Defence had been denied".

His fears were shared by those on his ship. A sailor on the Good Hope wrote home from Stanley "From now to the end of the month is the critical time, as it will decide whether we shall have to fight a superior German force coming from the Pacific before we can get reinforcements from home or the Mediterranean. We fell that the Admiralty ought to have a better force here. But we shall fight cheerfully whatever odds we have to face".

Fears were also growing on the Falkland Islands. At the Governor's orders, women and children were evacuated from Port Stanley to surrounding islands.

On 26th October, on his way to the rest of his squadron, Cradock tried once more to have Defence allocated to his forces. He signalled the Admiralty about supply difficulties, and in response to a query about his movements: "With reference to orders ...received on October 7th to search for the enemy and our great desire for early success, consider it impracticable on account of Canopus' slow speed to find and destroy enemy squadron. Consequently have ordered Defence to join me after calling at Montevideo for orders. Canopus will be employed on necessary convoying of colliers ...".

When the signal arrived in London on 27th October, the Admiralty was in the midst of crisis over the position of the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis of Battenberg, who was under extreme pressure from an unpleasant campaign against him because he had been born in Germany. Churchill did not therefore see Cradock's signal until the following day, after Battenberg had resigned. In the absence of a response, Cradock (as the senior naval officer) instructed Stoddart to send Defence, without seeking Admiralty approval. Stoddart immediately telegraphed the Admiralty to request two fast cruisers in place of Defence. That evening, Churchill countermanded Cradock's order:

"Defence is to remain on east coast under orders of Stoddart. There will then remain sufficient force to meet the hostile cruisers on whichever side they appear on the trade routes. No ship is available for neighbourhood of Cape Horn".

On 27th October, Good Hope joined Glasgow, Monmouth, and Otranto in the Vallenar roads, where they were coaling. Hoping to receive further clarification or modification of his orders, Cradock sent Glasgow into Coronel to collect any messages. She also took outgoing mail from the squadron. Touring the wardrooms, Lieutenant Hirst found officers were fatalistic: "Two of the lieutenant commanders in Monmouth, both old shipmates, took me aside to give me farewell messages to their wives - "Glasgow has got the speed" [they said] "so she can get away; but we are for it"."

On 29th October, Cradock and his squadron left Vallenar, to go north. Just as they were leaving, Canopus arrived. Once again her captain reported engineering problems - she needed another twenty four hours repair work. Cradock told her to anchor, do the work, and follow as soon as possible.

That day, Glasgow, on her way to Coronel, intercepted heavy wireless traffic, which appeared to come from Leipzig (von Spee had told all his ships to use Leipzig's call sign). Expecting to see the enemy at any minute, and not wanting to get trapped in port, she delayed entering Coronel for two days. Finally, on October 31st, she went in to send and collect messages. Once again wireless traffic was heavy, so she left promptly the next morning to meet Good Hope and the rest of the squadron.

At around lunchtime on November 1st, Glasgow brought Churchill's signal to Cradock on Good Hope. Lieutenant Hirst wrote later: "The words "sufficient force" must have seared the soul of a fearless and experienced officer whose impetuous character was well-known at the Admiralty ... Tired of protesting his inferiority, the receipt of this telegram would be sufficient to spur Cradock to hoist, as he did half an hour later, his signal, "Spread fifteen miles apart and look for the enemy"."

The Battle

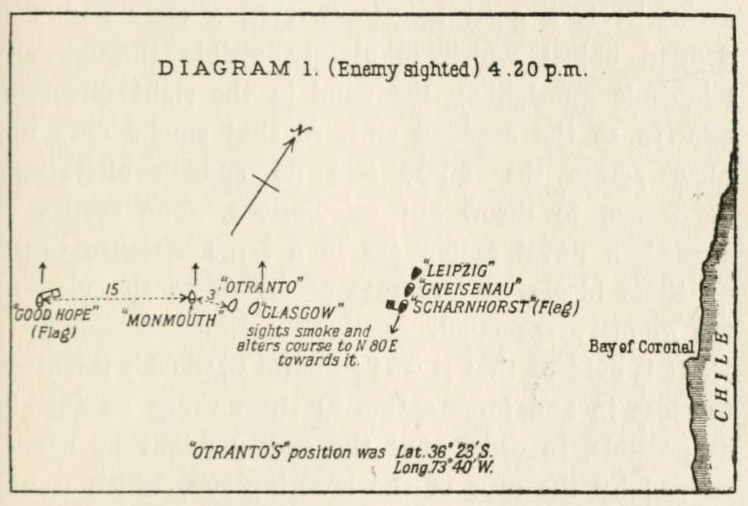

Cradock's squadron formed a line of search east to west, fifteen miles between ships, heading north at ten knots. Nearest the coast was Glasgow; next was Monmouth, then Otranto, and farthest west, Good Hope.

Coming south, fairly close to the coast, was Von Spee, in search of Glasgow, whose arrival in Coronel the day before had been reported to him by a German supply ship. His squadron was strung out - Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Leipzig were in front and the other two light cruisers behind.

The day had dawned sunny and clear with a strong south wind and by midday this had strengthened to a Force Seven from the southwest. The two squadrons sighted each other at 4.20pm, just as the sun was beginning to sink.

Neither side expected to meet the other in force - Cradock was expecting to meet Leipzig, and Von Spee was expecting to meet Glasgow. Although Good Hope, Monmouth and Glasgow were faster than the German heavy cruisers, Otranto's best speed of 16 knots was inferior to all the German ships. Cradock could have turned away, but this would have meant leaving Otranto to shift for herself - and of course, he had been ordered to "destroy the German cruisers". At 5.10pm he ordered all ships to head towards the enemy, and formed them into a single line, Good Hope leading, then Monmouth, Glasgow and Otranto.

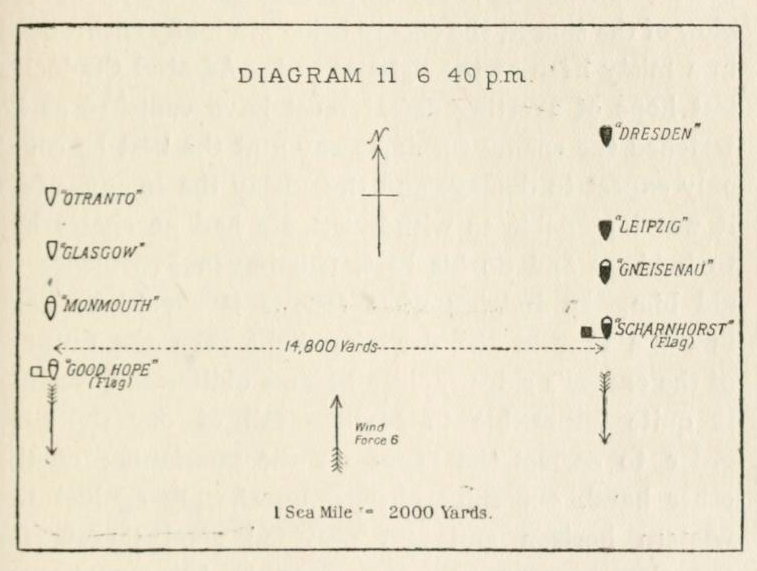

For almost an hour, the two lines of ships moved south in parallel, about 14000 yards apart, over heavy seas. For a little while, the British had an advantage, lying between the enemy and the setting sun - the low sun would blind the gun layers, whilst at the same time lighting up the German ships as targets. Cradock decided to force an immediate action, but had to come close enough to use his 6 inch guns (those not flooded by the heavy sea). At 6.18pm he increased speed to 16 knots and turned closer towards the enemy.

Von Spee, however, recognised this opportunity - or risk - and increased speed to 20 knots, moving closer to the coast, at a new range of 18,000 yards. Cradock could do nothing, and so continued to pursue.

At 6.50pm, the sun sank. The German ships were now indistinct against the coast, while the British ships were silhouetted against the sky. Von Spee altered course and brought his ships to within 12,300 yards. He opened fire at 7.04pm. Notwithstanding that all the ships were rolling heavily, the German gunnery was excellent. Within five minutes, Scharnhorst had struck Good Hope's forward gun turret and her foredeck exploded in flames. Gneisenau fired at Monmouth, striking her forecastle - at first Monmouth's returning fire was rapid, but Gneisenau was out of range; then Monmouth's fore six-inch turret was hit and in two huge explosions completely disappeared, and her firing became ragged. Good Hope continued to try to close the range, to bring the 6 inch guns to bear, but was hit repeatedly by Scharnhorst, while Gneisenau continued to fire on Monmouth. Flooded by heavy seas, Monmouth fell out of line, and gradually her guns ceased to fire. Both she and Good Hope were by this time in flames, presenting easy targets; but Good Hope continued to try to close the range.

At 7.42pm Good Hope mounted a final charge towards Scharnhost and Gneisenau, which moved out of her path and then, at a range of less than 5000 yards, fired rapid broadsides at her until she came to a halt. By 7.50pm, having absorbed more than thirty five direct hits, she was silent and burning. Then there was a tremendous explosion, she broke in two, and the forward section of the ship sank; followed some time after by the rest of the ship.

Once Good Hope was sunk Scharnhorst switched her fire to Monmouth and Gneisenau targeted Glasgow, which had attempted, but failed, to hit first Leipzig and then Dresden. From 7.15pm, Glasgow was engaging three ships, and she managed to score a hit on Gneisenau. However, by 8pm, when she realised that by firing, she was drawing the combined fire of the German squadron, who were using the flash of the guns as their target in the dark, she ceased fire. By extraordinary good fortune, she had been hit only five times, and only one hit had any significant impact. Her seaworthiness was not affected and she was able to steam away at full speed. Not a single man of Glasgow's crew was killed or wounded (though only ten parrots survived the battle).

At 8.15pm Glasgow found Monmouth trying to turn to the north, to get the undamaged stern into the large waves coming up from the south. The fires were out. The moon was out and the enemy was still near. Glasgow's captain, John Luce, said later: "I felt that I could not help her but must be destroyed with her if we remained. With great reluctance, I therefore turned to the northwest and increased to full speed". In addition, someone needed to warn Canopus, coming up from the south, which would otherwise face the enemy alone. As Glasgow left, she heard the crew of the Monmouth cheering.

Meanwhile, Nurnberg, which had been behind the rest of Von Spee's squadron when the battle began, and so had not so far been involved, came up, and found Monmouth underway, though listing heavily to port, so that the guns on that side were useless. Nurnberg's searchlight illuminated the White Ensign still flying and repair parties moving on the shattered decks. Monmouth did not fire, but nor did she lower her flag. At 9.20pm, Nurnberg opened fire, aiming high, but the flag was not struck. Then, Monmouth began to gather speed and turn toward Nurnberg, perhaps to bring her starboard guns to bear. As she turned, Nurnberg circled, and passed under her stern, which was high out of the sea. At point-blank range, Nurnberg fired and ripped apart the unprotected hull.

Later, her captain, Karl von Schonberg, wrote: "I fired until the Monmouth had completely capsized, which ... proceeded very slowly and majestically, the brave fellows went under with flags flying, an indescribable and unforgettable moment as the masts with the great top flags sank slowly into the water. Unfortunately, there could be no thought of saving the poor fellows. First, I believed that I had an enemy before me [in fact the smoke his lookouts had seen were his own squadron], secondly the sea was so high that hardly a boat could have lived in it. Moreover, all my ship's boats were secured before the action".

There were no survivors. 52 officers and 867 men were killed in Good Hope, including Cradock, and 42 officers and 693 men in Monmouth.

On the other side, no German officer or seaman had been killed; three on Gneisenau had been slightly wounded; the three German light cruisers had not been hit. But von Spee anticipated his ultimate fate. When Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nurnberg docked at Valparaiso to an enthusiastic reception, Von Spee was offered a bouquet of flowers. He refused them, saying "They will do nicely for my grave". To an old friend in Valparaiso, he confided: "I am quite homeless. I cannot reach Germany; we possess no other secure harbour; I must plough the seas of the world doing as much mischief as I can until my ammunition is exhausted or a foe far superior in power succeeds in catching me".

Though two ships of Cradock's squadron had been sunk, three escaped. Otranto had played no active role, and withdrew, seeing that her 4 inch guns were totally unfit for any offensive purpose in the circumstances and that she was providing a target in the line which the enemy could use for ranging. She headed 200 miles west into the Pacific and then turned south and east around Cape Horn.

Glasgow headed west from the battle at full speed and then turned south towards Canopus. As she headed south the German jamming of wireless transmission receded and she was able to tell Canopus what had happened. The two ships met at the eastern end of the Magellan Straits and on 8th November, a week after the battle, they arrived in Port Stanley. Having recoaled, they were due to head for the River Plate, but Canopus once again was near breakdown and needed more time to repair engines. She was left in Port Stanley. Glasgow reached the River Plate on 11th November, and the following day she and Defence left together for the British coaling base at Abrolhos Rocks in the middle of the South Atlantic. All naval forces were to be withdrawn until reinforcements could arrive.

A map giving an overview of the engagement is available at the Coronel Memorial website.

What happened next will be the subject of a separate article, to be published on the anniversary of the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

The news reaches Dartmouth

News of what had happened came through gradually and it took some time for families to receive official confirmation of their loss.

Reports of the battle reached the Admiralty on 4th November, initially from German sources. The next day the Admiralty issued a preliminary public statement, which formed the basis of an article published in newspapers. On 6th November, the Dartmouth Chronicle reported as follows:

The Reported Naval Battle

The Alleged Disaster to HMS Monmouth

Anxiety at Dartmouth

The German claim that HMS Monmouth has been sunk, and other cruisers damaged during a naval engagement in the Pacific, has caused great anxiety at Dartmouth owing to the presence aboard the Monmouth of a number of local men, and several cadets from the Royal Naval College.

The newspaper went on to quote the Admiralty's statement:

Rumours and reports have been received at the Admiralty from various sources of a naval action having taken place off the Chilean coast. The Admiralty have no confirmation of this, and such accounts as they have received rest admittedly on German evidence.

It is reported that the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Leipzig, Dresden and Nurnberg concentrated near Valparaiso, and that the engagement was fought with a portion of Admiral Cradock's squadron on Sunday November 1st. The German reports assert that the Monmouth was sunk and the Good Hope very severely damaged. The Glasgow and the Armed Auxiliary cruiser Otranto broke off the action and escaped.

The Admiralty cannot accept these facts as accurate at the present time, for the battleship Canopus, which had been specially sent to strengthen Admiral Cradock's squadron and would have given him a decided superiority, is not mentioned in them, and further, although five German ships concentrated in Chilean waters, only three have come into Valparaiso Harbour. It is possible, therefore, that when full accounts of the action are received, they may considerably modify the German version.

The newspaper then listed the following:

Lieutenant Wilfred D Stirling, who had spent some time at the Naval College

This was not of course the full list of Dartmouth men aboard the Monmouth.

The following week, 13th November, the Dartmouth Chronicle reported:

The Secretary of the Admiralty announces that in the absence of further information the loss of HM Ships Good Hope and Monmouth must be presumed and casualty lists will be published shortly.

The announcement will be received with great sorrow in the borough, especially in view of the fact that a number of Dartmouth men were on board the Monmouth, and their relatives, with whom the deepest sympathy is felt, have received official messages from the Admiralty conveying the news of the loss of the ship.

In addition to Lt Wilfred Stirling, the newspaper mentioned Engineer Commander John Barton Wilshin. Wilshin was not a native or resident of Dartmouth but had "played regularly for the Kingswear Cricket Club during the 1911 season" and was "a keen Rugby man and prominent player for the Engineer Students XV, when that was the power in the Devon football world.

The newspaper once again listed the ten cadets, and to the five names of Dartmouth men published on 6th November, a sixth was added, C Lock.

On November 20th, the newspaper reported that a memorial service "of a very impressive character" had been held the preceding Wednesday in St Saviour's for the local men "who are presumed to have lost their lives. The service was largely attended and the congregation included a number of the relatives of the unfortunate men". The newspaper continued by publishing the report of the action received from HMS Glasgow, which must have left very little doubt about the fate of Monmouth and Good Hope.

In that edition, and in the following edition, of the Chronicle, were also published obituary notices of the Dartmouth men who had lost their lives (see their entries in our database).

Endnotes

1 in fact, ten

2 some sources say she departed Plymouth on 6th August

Sources

The account here is drawn principally from:

History of the Great War - Naval Operations, Vol 1, by Sir Julian S Corbett, available on line at naval-history.net

Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea, by Robert K Massie, publ Vintage 2007

The letter from Bandsman William Wileman Hart, together with much more material, is available on The Coronel Memorial, a website which is a memorial for all those who lost their lives in the battle:

The Battle of the Falkland Islands by Commander H Spencer Cooper - from which the two diagrams in this article were taken.