William Robert Blake

Family

William Robert Blake was born in Dartmouth on 27th December 1892 and baptised in St Saviour on 23rd February 1893. He was the eldest son of Robert Blake and his wife, Elizabeth Ann Pitman.

Robert Blake was born in Stoke Fleming but had come to Dartmouth by way of Dittisham. His father, Roger Huddy Blake, was a farm labourer. Robert was the youngest of a large family. For much of his early life, he lived at Old Mill Cottages, at the head of Old Mill Creek, north of Townstal, with his parents. In the 1891 Census, he was recorded living there with his parents and his elder brother, working as a blacksmith. By the time of his marriage to Elizabeth Ann Pitman, on 20th November 1892, however, he had moved into Dartmouth. The entry in the marriage register records that he lived in Crowther's Hill and was working as a labourer.

Elizabeth Ann had been born in Dartmouth. She was the second surviving daughter of Richard Pitman and his wife, (Elizabeth) Charlotte Widdicombe. Richard came originally from Somerset. He had joined the Royal Navy for ten years as a Boy 1st Class, in 1855. In 1867, two years after leaving the service, he had married Charlotte, who was from Dartmouth. The couple had settled in Dartmouth, where Richard worked as a waterman in attendance on HMS Britannia.

Tragically, Elizabeth lost her father when she was four. The Dartmouth and Brixham Chronicle of 21st January 1876 reported the inquest into his death - he had been found drowned near the entrance of Redway & Son's patent slip, at Sandquay, on the previous Friday. He had left the house the day before at 5pm for HMS Britannia, being employed as a boatman to take passengers to and from the ship; he had put the cook's assistant, James Phillip Bide, on board at 9pm, and had then gone into the Floating Bridge Inn for a drink and some tobacco. At 9.15pm, William Hitchings, ropemaker on HMS Britannia, had given him a light for his pipe. Hitchings said: "I asked him if he was going home, and he said his duty was not over". However, he had not carried any other passengers. The night was reported to have been windy and the water rough, with a strong tide. Richard's body had been found the next morning and his boat had also been found adrift. One of the witnesses reported that Richard Pitman was a good swimmer, and had told his wife of a narrow escape he had had from drowning when in Newfoundland. The verdict was "Found Drowned, probably by accident"; and "most of the jury and witnesses gave their fees for the benefit of the widow and four children", which amounted to 15s.

A letter in the paper of the same date from "The Hermit of the Tower" appealed to readers to give generously as "the poor woman (ie Charlotte), who is the daughter of a fellow townsman, has been left perfectly destitute, with... four small children (the youngest not three weeks old) depending entirely upon her exertions for their daily bread". Four weeks later the paper announced that £13 had been raised, and that "through the liberality of the officers and men of HMS Britannia, the poor woman has been provided with a good serviceable mangle". Evidently Charlotte put the money to good use, for the 1881 recorded her at 1 Coombe House, working on her own account as a laundress. Charlotte's mother and father, Thomas and Elizabeth Widdicombe, also lived with the family, no doubt to assist with care of the children as well as helping to make ends meet. By 1891, all her daughters, including Elizabeth, were also working with her.

After his marriage to Elizabeth in 1892, Robert Blake worked principally as a coal porter, or "lumper", as they were known in Dartmouth. This was a hard trade, labour intensive, but working on the basis of casual employment. Because there were always several companies competing to coal any ship, the "lumpers" had to wait "on the stones" hoping to be included in a gang employed to shift the coal. When a ship came into harbour to coal, the lumpers had to race to the coaling hulk in 6 or 8-oared gigs, which were kept moored against the quay wall. The first to reach the hulk got the job - loading the coal from the hulk into baskets, and then loading up the bunkers of the vessel needing the coal. Wages were low - the daywork rate per person was 4s, and lumpers could not rely on working every day.

The family lived in Silver Street, now Undercliff, and grew steadily. After William Robert was born in 1892, there followed Ada Louisa, in 1894; Alfred Benjamin, in 1896; Henry Roger, in 1898; Elizabeth Milvinia, in 1900; Gordon Harold, in 1902; Ellen Nora May, in 1904; Edward Newyn, in 1906; and finally Percy Ralph, in 1909. William, it seems, felt the lure of the sea, and followed his grandfather into the Navy, notwithstanding his grandfather's ultimate fate. On 1st March 1909, only a few weeks after the birth of his youngest brother, William joined the Navy as a Boy 2nd class. Seaman Boys entered between the ages of fifteen and sixteen for 12 years service, starting at the age of 18. As William was already sixteen, he understated his age by about six months. He had worked as a "rivet boy" before joining.

His naval record describes him as 5' 4" in height, with light brown hair, blue eyes, and a "fresh" complexion. Apparently, he already had a sweetheart - one of his tattoos was a "heart with clasped hands and words 'Love to Carrie'."

Service

William joined HMS Impregnable at Devonport for his initial training. He then spent most of 1910 on the armoured cruisers HMS Leviathan, HMS Sutlej, and HMS Royal Arthur, all at that time in the reserve fleet, based in and around the UK.

He had his first opportunity to see the world with his appointment on 7th October 1910 to HMS Kent, a Monmouth class armoured cruiser at that time serving on the China Station, and he was recorded on board her at the time of the 1911 Census. On 18th May 1911, when the Navy thought he was eighteen, he was rated Ordinary Seaman, and while still on HMS Kent, achieved the rate of Able Seaman six months later, on 30th November. He travelled back to the UK on HMS Royal Arthur, arriving in Portsmouth on 8th February 1912.

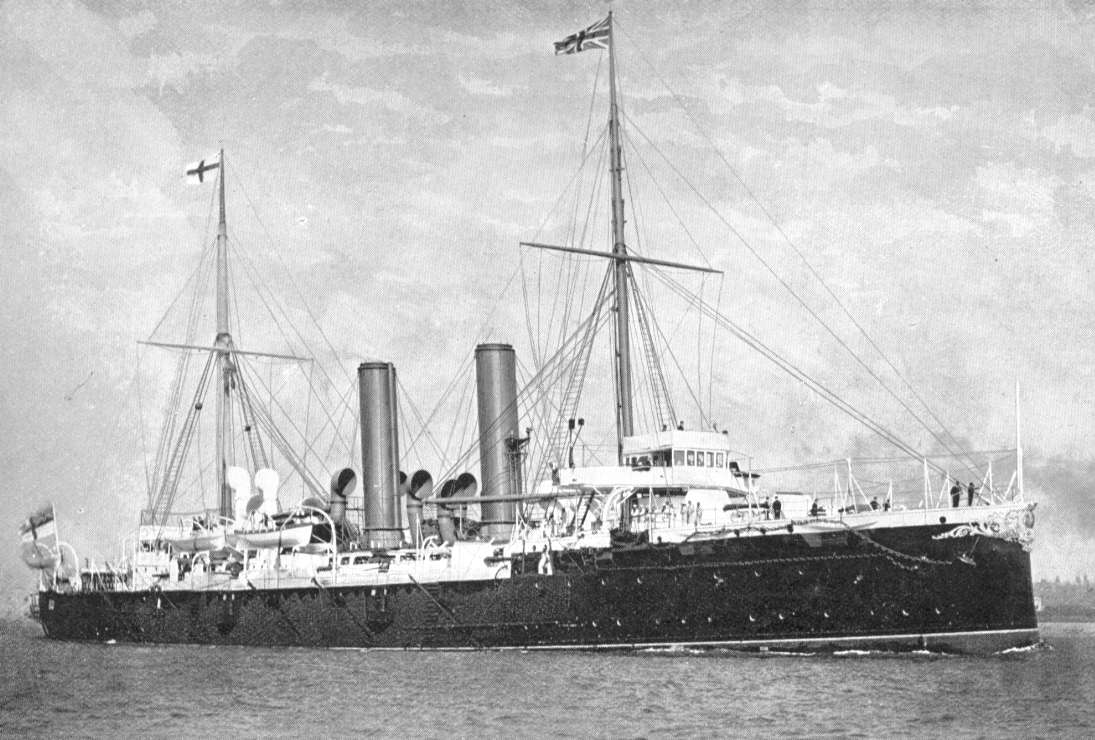

After a period ashore, he was next appointed to HMS Blake, his namesake - named for Admiral Robert Blake, commander of the Protectorate Navy, sometimes called "Father of the Royal Navy". HMS Blake was launched in 1889 as a cruiser but by the time William was appointed to her she had been converted to a destroyer depot ship. His naval record indicates that he was appointed to HMS Blake herself to begin with and then on 15th July 1913 to HMS Nymphe, an Acorn-class destroyer. How long he remained on Nymphe is not clear from his record - it is quite likely he was transferred to other destroyers. If he was still on Nymphe at the outbreak of war, he would have found himself part of the Second Destroyer Flotilla, serving in Home and Atlantic waters. The Flotilla was attached to the Grand Fleet on 24th November 1914.

Death

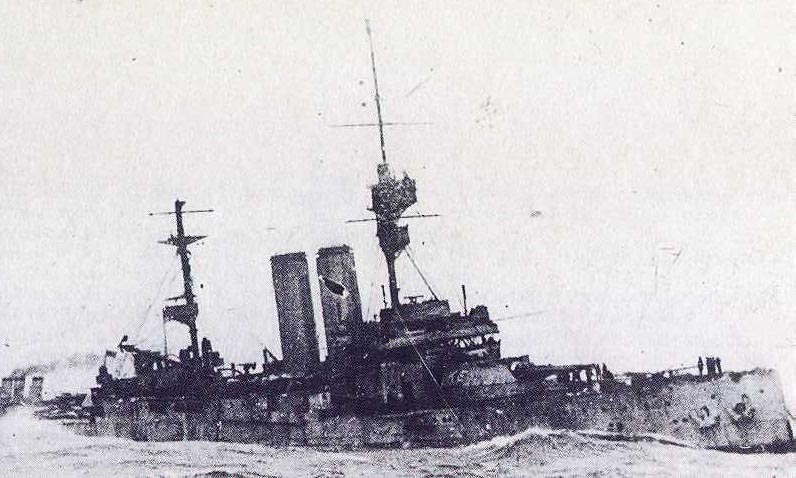

At some point late in 1915, William was transferred to HMS Musketeer. Musketeer was an "M" class destroyer, more up to date than Nymphe. She was one of ten of this class built at Yarrows, on the Clyde. Shipbuilders were allowed to vary aspects of the design if this could deliver improved performance, and the "Yarrow specials" gave slightly better endurance than the Admiralty's own design. Visually, she had two funnels rather than three. She was launched on 12th November 1915.

On 6th January 1916, the pre-dreadnought battleship, HMS King Edward VII, serving with the Grand Fleet, departed Scapa Flow at 07.12 for Belfast, where she was to undergo a refit. At 10.47, off Cape Wrath, she struck a mine. The official naval history describes what happened:

"At first it was believed to have been the work of a submarine, and the Kempenfelt and twelve destroyers were hurried to her assistance. No minefield was known to exist in the vicinity, and the Africa, proceeding to Scapa, had passed the spot safely a few hours before. Efforts were made to tow the doomed battleship, but by 4.00pm, after nine hours struggle, it was clear that in the heavy weather that prevailed she was doomed. Captain C Maclachlan therefore decided he must abandon his ship. In spite of the sea that was running the destroyers Musketeer, Marne, Fortune and Nessus were skilfully brought alongside, and every soul was saved, and four hours later the stricken ship turned over and sank".

It was not known until some time afterwards that the minefield had been laid by a converted merchant ship, the Moewe. Disguised as a Swedish trader, she had put to sea from Germany on 29th December 1915 and headed north. She managed to evade detection completely, and laid a field of 252 mines across the western entrance of the Pentland Firth, in what the naval history describes as a "gale of wind and snow". Having completed this task successfully, she then went out into the Atlantic and south to La Rochelle, where she laid a second minefield on 9th January 1916. She spent several weeks capturing and sinking merchant vessels (though fortunately sending their passengers and crews to safe havens ashore); successfully evaded capture herself; and returned to Germany on 5th March. The announcement of her prizes made clear that HMS King Edward VII had encountered the Moewe's first minefield - and, indeed, that British defence of home waters was far from complete.

Although the rescue of the King Edward VII's crew had been successful, with all members of the battleship's crew taken off, it seems that either during it, or shortly after, the Musketeer suffered two casualties. The precise circumstances are not known. Clearly the rescue took place in very difficult sea conditions. William's naval record states only that he was "washed overboard from Musketeer". An account in the Manchester Evening News on 18th January of the official notification of the death of the other Musketeer casualty, AB Alfred Lewis, states that he "was drowned on January 6th during a gale, after having assisted in rescuing the crew of the ill-fated King Edward VII". However, the naval casualty information on naval-history.net states that the casualties were due to Musketeer being damaged by the fittings of the sinking ship, after rescuing the crew.

The Dartmouth Chronicle of 14th January carried the following short item recording William's death:

Dartmouth Naval Seaman drowned

On Saturday, Mr and Mrs R Blake of 1 Undercliff Dartmouth, received a communication from the Admiralty that their son, William Robert Blake, able seaman, on HMS Musketeer, had been lost overboard and drowned.

Commemoration

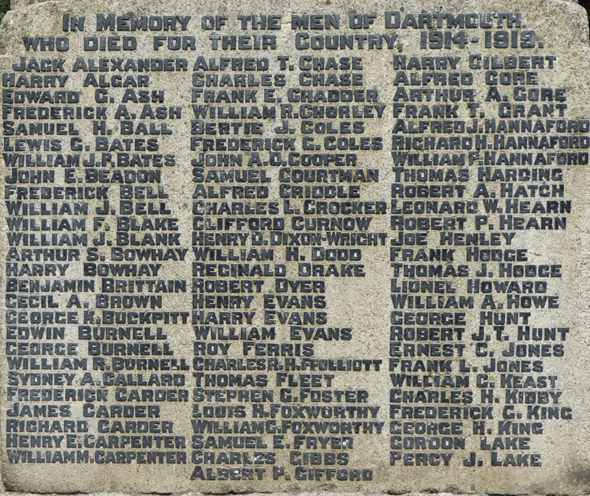

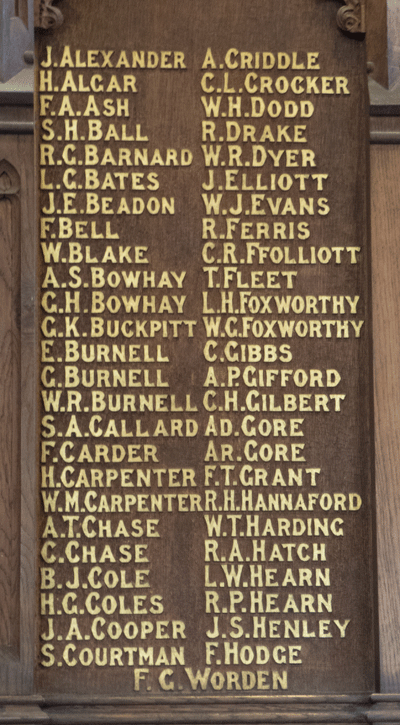

William is commemorated in Dartmouth on the Town War Memorial (where his middle initial is incorrect) and the St Saviour's Memorial Board. Like all those lost at sea and with no known grave, he is also commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial.

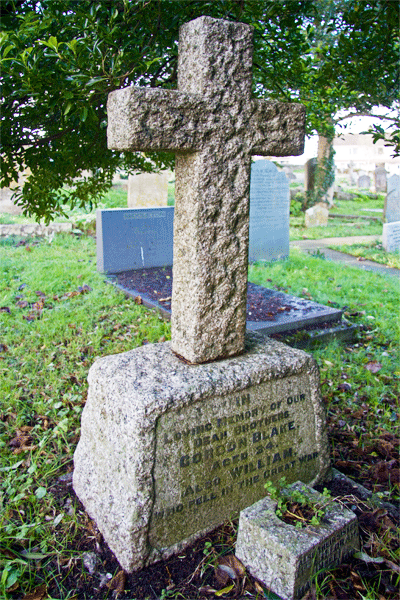

Some thirty years after William's death, his younger brother Gordon also died and was buried in the churchyard of St Clements, Townstal. The family commemorated the two brothers together. Their parents also were buried in St Clements churchyard, Robert in 1924, and Elizabeth Ann in 1950.

Sources

Royal Navy service record for William Robert Blake, ADM 188/654/3711, fee chargeable for download

Royal Navy service record for Richard Pitman, ADM 139/199/19867, fee chargeable for download

History of the Great War, Naval Operations Vol III, Chapter XIII, by Sir Julian Corbett, 1923, second edition 1940

Naval casualty information for January 1916

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Blake |

| Forenames: | William Robert |

| Rank: | Able Seaman RN |

| Service Number: | J/3711 |

| Military Unit: | HMS Musketeer |

| Date of Death: | 06 Jan 1916 |

| Age at Death: | 24 |

| Cause of Death: | Washed overboard and drowned |

| Action Resulting in Death: | Rescue of crew of HMS King Edward VII |

| Place of Death: | Off Cape Wrath, Scotland |

| Place of Burial: | Commemorated Plymouth Naval Memorial |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | Yes |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | Yes |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | Yes |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | Yes |

| On a Private Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Private Memorial: | In St Clements |

| On Another Memorial? | No |