Frederick Francis Charles Tillier

Family

Frederick Francis Charles Tillier was neither born nor lived in Dartmouth. The war brought him to the town at the very end of his life.

Although his naval records give his date of birth as 12th December 1894, his birth was registered in the first quarter of 1897 - so he was probably born on 12th December 1896. He was the only son and second child of Frances Tillier and Frederick Vizzard.

Frances Tillier was the daughter of Charles Tillier, a nurseryman, and his wife Martha. At the time of the 1891 Census, she lived in Chobham Road, Ottershaw, near Chertsey, with her widowed father, Charles, and her sister Mary. The Census recorded Frances as a "Grocer"; in Kelly's Directory of 1891, she was shown as "(Miss) Frances Tillier dressmaker and shopkeeper", so it seems she ran her own grocery shop as an independent trader.

Charles Tillier died on 25th February 1894 and Frances appears to have inherited the family home (or its lease) in Chobham Road. At about this time (if indeed not before) she entered into a relationship with Frederick Vizzard, a nurseryman - we have not been able to trace a marriage record. Frances had her first child at the comparatively late age of 41. Her daughter Frances Daisy, whose birth was registered in the name of Vizzard, was born in 1894 and baptised at St Paul's, Addlestone, on 18th April 1895. The baptism entry shows her as the daughter of Frederick and Frances Vizzard. Her son, Frederick Francis Charles, was baptised at St Paul's on 1st September 1898, shown likewise in the baptism register as the son of Frederick and Frances Vizzard; however, his birth was registered in 1897 in the name of Tillier.

The 1901 Census recorded Frederick, Frances, and the two children Frances and Frederick, age 6 and 4, living at 1 Chobham Road, Surrey. Frederick Vizzard was a "nursery gardener". It seems that Frances (senior) had given up her grocery shop, presumably because of her family responsibilities.

By 1905, according to Electoral Registers, Frederick Vizzard was living in 6 Ongar Cottages, Addlestone; whether Frances and their two children were still living with him is not known. He moved to West Byfleet in 1907; Walton Road, Woking in 1908, and nearby to Eve Road, Woking, in 1909. He died early in 1909, and afterwards, although describing herself as a widow, Frances (and her children) seem to have reverted to using the name Tillier. By the time of the 1911 Census, Frances was living in Reading at 2, John a'Larder's Buildings, Bridge Street. She was recorded as the "housekeeper", in the household of Arthur Franklin, a signal fitter on the Great Western Railway, and his four young children. Arthur's wife Sarah Jane had died of consumption in December 1909 and evidently Arthur needed support in caring for his four sons, the youngest of whom, Ernest, was three.

However, Frances' own children were not living with her. She had obtained a place for Frances Daisy at the "Friends Rescue Home", at 10 Laura Place, Clapton, London, which was run by the Society of Friends and had room for 15 girls under 23. So far, we have been unable to trace Frederick's whereabouts in 1911. By late 1915, however, he was living in Reading, at 12 Highgrove Street, and his Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve record states that he was working as a labourer. Frances would appear by then to have returned to Surrey - Frederick named her as his next of kin and her address is recorded as Haversham Cottage, Hersham Green, Walton on Thames. By 1918, she had moved to Felcott Road, Walton on Thames; later, Frances Daisy joined her there.

Service

Frederick joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on 18th October 1915 "for hostilities". He gave his date of birth as 12th December 1894, overstating his age by two years - he was nineteen. His records state that he was 5' 7½" tall, with brown hair and grey eyes. It seems unlikely that he had any previous sea experience, and he was first allocated to the Royal Naval Division.

The Royal Naval Division was established on 3rd September 1914 - for its rather unusual origins and early history, see the story of William Henry Wellington. Since April 1915 the RND had been fighting as infantry in Gallipoli, and by October 1915, had suffered severe casualties. While Frederick was undergoing initial training at the depot at Crystal Palace, the Government took the decision to evacuate the peninsula. The RND, which was holding part of the front line at Cape Helles, was amongst the last to leave, overnight on 8/9th January 1916.

At this point the RND reverted from Army to Naval command in the Eastern Mediterranean. For a short time, one brigade of the Division provided garrison troops for Tenedos, Imbros and Mudros, while the other was sent to hold a section of the Salonika front at the Gulf of Stavros. In the meantime, there was a debate at senior levels about the future of the Division. Eventually the decision was made that it would go to France, with the addition of four new battalions from reserves at the depot. However, there were insufficient officers and men to fully reinforce the Division, so eventually it was brought up to full infantry strength by the addition of an army brigade (the 190th).

While all this was going on, Frederick, who had joined at the rate of Ordinary Seaman, was rated Able Seaman on 4th May 1916, indicating he had completed his training. On joining the RND, he probably expected to be sent to Gallipoli, but he was not sent to France. The Admiralty retained the right to withdraw officers and men commissioned or enlisted in the Naval and Marine forces for sea service at any time; and Frederick's service took this path.

On 5th May 1916, he was withdrawn from the RND and retained at the Crystal Palace depot (HMS Victory VI), and on 14th July 1916, posted to Portsmouth Barracks (HMS Victory I). He then joined HMS Excellent on 14th September 1916 for gunnery training. Once qualified as a Seaman Gunner, he was appointed on 19th December 1916 to "Defensively Armed Merchant Ships" (HMS President III), having been rated Acting Leading Seaman for this purpose.

The U-boat war against merchant shipping was by this stage having a severe impact. As Robert Massie puts it:

Admiral] Jellicoe had come to the Admiralty to deal with the submarine menace, but once in office and seeing its dimensions, he was shaken. "The shipping situation is by far the most serious question of the day", he wrote to [Admiral] Beatty at the end of December 1916. "I almost fear it is nearly too late to retrieve it. Drastic measures should have been taken months ago to stop unnecessary imports, ration the country, and build ships. All is being started now, but it is nearly, if not quite, too late." Late was better than never; the effort to build merchant ships faster than the enemy was sinking them was set in motion … new protected trade routes for merchantmen sailing to Britain [were] laid out … Destroyers and smaller craft were deployed to patrol these highways. More mines were laid and more merchantmen were armed …

Another approach was the use of "Q"-ships, with hidden armament, to act as decoys - see, for example, the story of John Bellett Wood. In April 1917, the Admiralty introduced the convoy system for merchant shipping more widely (it had already been in use for ships carrying coal to France), and from about this stage of the war, the Royal Navy also was able to draw on the American Navy's assistance. New technology also played a significant part in countering the submarine threat. For example, the first depth charges were ordered in August 1916, and by early 1918, most anti-submarine craft were equipped with 35-40 (the depth charge was a metal can or barrel containing explosive which was detonated by a pressure fuse set for a specific depth).

The arming of merchant shipping had begun in 1915, firstly chartered colliers, and then extending to some of the larger classes of merchant ships engaged in overseas trade. By November 1918 there were 4203 defensively-armed merchant ships, while 1684 had been sunk, making a total of 5887 ships fitted altogether. Defensive armament, though light, was seen as having deterrent potential - even if only limited damage was likely to be caused, the threat of this damage might drive the U-boat away. Some figures for the year from 1st January 1916 to 25th January 1917 suggest that the armament was of some assistance:

| Attacked | Escaped | Sunk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defensively armed ships | 310 | 236 | 74 |

| Unarmed ships | 302 | 67 | 235 |

However, no defensively armed ship ever sank a U-boat, and as the figures show, many armed ships were sunk. Norman Friedman suggests that their principal value may have been to keep up morale amongst masters and crews of merchant shipping.

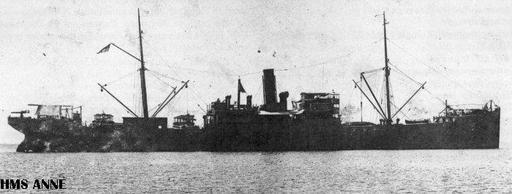

Frederick's RNVR record does not show his DAMS appointments by ship and no other information has come to light about where and in which ships he served. We know only that by May 1918, he was serving in the steamer Anne, built at Bremerhaven in 1911 for the German shipping company R C Rickmers, and originally named the Anne Rickmers.

The Anne had already had an adventurous war. In 1914, at the outbreak of war, when in Port Said, Egypt, she was seized by the British and requisitioned for service to operate seaplanes, and during 1915, supported Allied operations in Syria, Palestine and the Sinai peninsula. In July 1915 she was fitted with a 12-pounder gun (later exchanged for an anti-aircraft gun) and commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Anne, continuing to operate seaplanes as part of the East Indies and Egypt squadron. In January 1917, she was part of an amphibious landing at Al-Wajh, during the Arab Revolt. After this she was used as a collier from Suez until paid off on 8th August 1917. From 29th January 1918, she reverted to merchant shipping, being managed as a collier by F C Strick & Co for the "Shipping Controller" (a government post set up in 1916 to regulate and organise merchant shipping). So it would appear that Frederick joined her at or after that date.

Death

On 25th May 1918, the Anne was en route from Tyne to Genoa with coal. Between Berry Head and the entrance to Dartmouth Harbour, she was torpedoed by UB 74, commanded by Ernst Steindorff.

UB 74 was a type UB III U-boat, designed for coastal waters, constructed at the AG Vulcan Shipyard in Hamburg. She carried a crew of up to three officers and 31 men and was armed with ten torpedoes and an 8.8cm deck gun. She was commissioned into service on 24th October 1917, part of the Flandern 1 Flotilla. Ernest Steindorff took over command on 31st January 1918. He had a considerable record as a U-boat captain. During 1917 and the first four months of 1918, he had sunk 29 ships (including 1 warship) and damaged another five ships.

This particular patrol had been challenging. UB 74 had passed through the Dover Straits on 12th May, been rammed by the steamer Nidd off Beachy Head on 13th May (though without damage to the U-boat's inner hull), and on 14th May, missed a steamer (the Egbet) with a torpedo. On 18th May, however, off the Ile d'Yeu, UB 74 had sunk an American steamer, the John G McCullough, causing one casualty, though the submarine probably sustained some damage from a depth charge. On 23rd May, off the Lizard, UB 74 sank the British steamer Skaraas, causing nineteen casualties.

The Anne was lucky - she was damaged, but not sunk. However, according to his RNVR record, Frederick was "very seriously injured" during the encounter. The Anne was able to bring him into Dartmouth, where he was taken to the Cottage Hospital. His record notes that he "succumbed to his injuries" and died the following day, 26th May 1918. He was the only reported casualty of the attack.

Ernst Steindorff and his crew also died that day. Keen to attack steamers in a convoy off Portland, he failed to notice the armed yacht HMS Lorna, on escort duty. According to Robert Grant:

The armed yacht Lorna was escorting a convoy south of Portland at the eastern end of Lyme Bay when she sighted a periscope only thirty yards away. Since it was turned away from her to watch an approaching ship, she was able to approach to ten feet before it dipped. Lorna passed over the spot and dropped one depth charge set to fifty feet, then another. Amid the turbulence four objects could be sighted and cries of "Kamerad" and "Help" heard. Determined to destroy the U-boat, she dropped one more depth charge and killed three swimmers outright before picking up the fourth along with a cap marked Unterseeboots Abteilung. The survivor, who died after three hours, stated that the submarine was UB74, a week out of port, which had sunk three ships.

Reports of the encounter later published in several newspapers not surprisingly omitted the detail that the third depth charge had killed three survivors. This example is from the Whitby Gazette of 16th August 1918:

Details of the sinking of a U-boat by one of our armed yachts in the English Channel are now available. Just after sunset an SOS signal was picked up by the yacht, which diverting several steamers from the danger zone, sighted, half an hour later, the periscope of a submarine, which was apparently preparing to attack a merchantman.

Full speed was ordered, and the yacht drove right over the submarine just as the periscope disappeared, a distinct jar pointing to the probability that she had rammed the conning-tower. Two depth charges were then dropped.

While bringing his vessel round to pass over the spot again, the captain of the yacht observed a disturbance in the sea, in the centre of which was a bubbling and rush of water, evidently caused by volumes of air escaping to the surface. A third depth charge was dropped in the centre of the disturbance, which presently died away. One survivor, covered with a thick coating of oil, was picked up. Everything possible was done for him on board, but he had sustained serious internal injuries, and after remaining in agony for three hours, died.

In recommending the captain of the yacht, his superior officer points out that this lieutenant RNR "showed great promptness, not only in keeping other merchant shipping clear of the danger area, but in attacking and destroying the submarine" and concludes by saying: "His attack was marked by quick decision, good seamanship, and sound judgment".

UB 74 was lost with all hands - a total of 34 dead (including the survivor).

Both SS Anne and HMS Lorna survived the war.

Frederick Tillier was buried in St Clements churchyard, where his grave is marked with a Commonwealth War Graves Commision headstone.

Commemoration

As Frederick had no family or other social connection with Dartmouth, he was not commemorated on public memorials in the town.

However, he is commemorated, as Frederick Tillier, on the Great War Memorial Plaque in Christchurch, Reading, close to where he lived before he joined the RNVR.

Sources

Royal Naval Division service record for Frederick Francis Charles Tillier Z/3594, available for download from the National Archives, fee payable, reference ADM 339/1/38463

Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve service record for Frederick Francis Charles Tillier Z/3594, available from the National Archives, fee payable, reference ADM 337/39/46

The Royal Naval Division, by Douglas Jerrold, 1923, reprint, Naval & Military Press

Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea, by Robert K Massie, publ. 2007, Vintage Books

Fighting the Great War at Sea, by Norman Friedman, publ 2014, Seaforth Publishing, Pen & Sword Books

Career of Ernst Steindorff and UB 74 from website uboat.net

Profile of UB 74 from website uboat.net

Ships of Frank C Strick & Co from website The Ships List

U-Boat Hunters: Code Breakers, Divers and the Defeat of the U-Boats, 1914-1918, by Robert M Grant, 2003, Periscope Publishing

Information Held on Database

| Surname: | Tillier |

| Forenames: | Frederick Francis Charles |

| Rank: | Leading Seaman RNVR |

| Service Number: | London Z/3594 |

| Military Unit: | SS Anne |

| Date of Death: | 26 May 1918 |

| Age at Death: | 21 |

| Cause of Death: | Died of wounds |

| Action Resulting in Death: | U-Boat attack |

| Place of Death: | Dartmouth Cottage Hospital |

| Place of Burial: | Buried St Clements Churchyard, Dartmouth |

| Born or Lived in Dartmouth? | No |

| On Dartmouth War Memorial? | No |

| On St Saviour's Memorials? | No |

| On St Petrox Memorials? | No |

| On Flavel Church Memorials? | No |

| In Longcross Cemetery? | No |

| In St Clement's Churchyard? | Yes |

| On a Private Memorial? | No |

| On Another Memorial? | Yes |

| Name of Other Memorial: | Christchurch, Reading, Berkshire |